John Wesley and the Principle of Ministerial Succession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Greetings from Our Bishop

WELCOME AND GREETINGS FROM OUR BISHOP Dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ, Welcome to the annual session of the Florida Conference of the United Methodist Church. We join together during these days as disciples of Jesus Christ and leaders in his mission. This year we will celebrate our calling to be “On Mission Together,” and our vision to cultivate courageous leadership, missional engagement and spirit-led innovation. Our conference will be marked by music and worship, study and prayer, debate and conferencing, fellowship and laughter, business and visioning. We will license, commission and ordain men and women for set apart leadership in the church. We will send clergy into congregational and extension leadership for the coming year. We will elect laity and clergy delegates to the 2020 General Conference. We will celebrate extraordinary faithfulness in response to natural disasters in our region, and we will process the outcomes of the recent Special Session of the 2019 General Conference. And we will return to our local churches, more aware of our connection as Florida United Methodists. Gathering at Florida Southern College in Lakeland, the Annual Conference will begin with the celebration of Holy Communion. Our keynote speakers will be extraordinary: Bishop Will Willimon of Duke Divinity School will be our conference preacher, and Dr. Dana Robert of Boston University will be our teacher. Dr. Gary Spencer will preach the memorial sermon and Dr. Cynthia Weems, dean of the cabinet, will give the cabinet’s report. Inspirational music will be led by Jarvis Wilson and Keith Wilson of Atlanta, Georgia. Our offerings will support the re-development of the Wesley Foundation at Florida A & M University, and the launch of a new church inside Lowell Women’s Prison in Reddick. -

F:(T/("J~/ R PROCEEDINGS

f:(t/("J~/ r PROCEEDINGS. THE RECENT DISCOVERIES OF W ESLEY JV\55. AT THE BooK ROOJY\. The Standard Edition of Wesley's Journal could scarcely have reached its present stage of comparative completeness but for discoveries. Ancient notebooks, letters yellow with age, a few choice men with leisure and inclination to read them and with knowledge of the niches into which they naturally fit, were found. Yet, as some would argue, the books and papers had never been actually lost. By sale, gift or marriage, they had passed from hand to hand, very often the hands belonging to heads that neither understood nor cared for such things, except as curiosities, which, like inscribed stones and Worcester china, were gaining money-value by age. But just because they were old and once belonged to men of note, they were securely guarded in strong rooms, Chubb's safes, or women's treasure-boxes. They were "lost" in "safe places." I once held in my hand a printed book, now fabulously valuable, which when shown to me had risen in price from two-pence to a hundred pounds. It was " found" on a street-barrow by a man who had eyes to see. But of the hundreds of Wesley MSS. which have passed through my hands not one, so far as I know, was ever "lost " in the book-barrow sense. Someone has always known of its existence, though perhaps for fifty or a hundred years no one has realised its intrinsic importance. This is true of nearly if not quite all of the Wesley MSS. -

Bishop J. W. Alstork, We Need to Impress Upon the White D.D., LLD

= Bishop J. W. Alstork, We need to impress upon the white D.D., LLD. people the fact that there are thou sands who are reaching out for better A. 1'1. E. Zioll Church living, for clean living, and that they Reaidellce: l'Iolltiomery. Alabama ought to be encouraged in this desire l.hSHOP AI.STOHK presiCles over the Ala and conduct. In a certain city, houses bama, Florida. and Mississippi conferences. of ill-repute are put in a section where He wus born in Talludegll, Ala., September some of the best colored people live, I, 1852. He studied lit night schools and and where their children are compelled worked on the railroad during the day as brakeman, baggageman, warehouse mun, to gaze upon the obscenity of this lewd cotton marker, and smnpler. Later, he class of white people, and cannot help attended Talladegu ollege und then tuught themselves. When the mayor of the city school. was appealed to, he said to the com He WllS cnIled to the ministry in 1878, and plainant, "H you do not like it, you after completing his theological course, in 1882, was appointed to some of the strong can sell out and move to another part churches of the denomination. He was of the town." financial secretary for his conference for eight H it were not for a few white friends years, and was then elected financial secretary we have, I don't know what would be for the entire connection, in which position come of us. It would help wonderfully, he served eight years. -

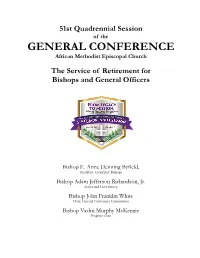

General-Conference-REVISED-Service-Of-Retirement-2021-07-05

51st Quadrennial Session of the GENERAL CONFERENCE African Methodist Episcopal Church The Service of Retirement for Bishops and General Officers Bishop E. Anne Henning Byfield, President, Council of Bishops Bishop Adam Jefferson Richardson, Jr. Senior and Host Bishop Bishop John Franklin White Chair, General Conference Commission Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie Program Chair The Service of Retirement for Bishops and General Officers IN OBSERVANCE OF The Fifty-first Quadrennial Session of the General Conference African Methodist Episcopal Church Orange County Convention Center Orlando, Florida Friday, The Ninth Day of July Two Thousand Twenty-One 3:10 – 4:00 pm EDT 9:10 – 10:00 pm SAST The Order of Service Bishop Adam J. Richardson, Jr. Worship Leader The Moments of Praise The Call to Worship Bishop Adam J. Richardson, Jr. Bishop: The Bible instructs us to give honor to those to whom honor is due. Today we gather to pay tribute to two Bishops and four General Officers for their years of service and labors of love in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. We salute them for a job well done. People: For them, O God, we give Thee thanks. Bishop: We thank you, O God, for their strength to bear burdens and their grace to share blessings. People: For them, O God, we give Thee thanks. Bishop: For their ministries, sacrifices, lives touched, services rendered, and sermons preached, People: For them, O God, we give Thee thanks. Bishop: For the sixty-nine collecJve years of Episcopal Service given by Bishops McKinley Young, VashJ Murphy McKenzie, and Gregory Gerald McKinley Ingram, we praise God for them. -

The Foreign Minister of Methodism

The Foreign Minister of Methodism By Warren Thomas Smith Saturday, September 18, 1784, may have dawned as just another day in Bristol, England, but in the province of God it was highly significant. “At ten in the morning we sailed from King—Road for New York. A breeze soon sprung up, which carried us with the help of the tides, about a hundred leagues from Bristol by Monday morning . .” so Thomas Coke made the first entry in his Journal, a little volume published in 1793 and dedicated to John Wesley. The small vessel was not unlike other ships of the time, yet it was playing a role in an important scene of church history. Three of the passengers were to open a new chapter in the religious life of America. Of these one was a dedicated Welsh gentleman who would travel at least a hundred thousand miles on a hundred separate voyages as the Foreign Minister of Methodism and Ambassador of Jesus Christ. Thomas Coke was sailing as the executor of John Wesley’s design for the people called Methodists. It is doubtful that this plump little clergyman, who stood just five feet one inch, fully realized the significance of the voyage he was undertaking. A church was about to be born, and he was to be a key figure in the first moment of its breathing. Background of the Time We cannot form an estimate of the life and work of Thomas Coke without considering the time-spirit in which he lived: (1) His was to be a background of war and threat of war. -

2021 Preacher Itinerary

51st Quadrennial Session of the GENERAL CONFERENCE African Methodist Episcopal Church Bishop E. Anne Henning Byfield President, Council of Bishops Bishop Adam Jefferson Richardson, Jr. Senior and Host Bishop Bishop John Franklin White Chair, General Conference Commission Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie Program Chair PROCLAIMERS OF THE GOSPEL THE OPENING WORSHP SERVICE Tuesday, July 6, 2021 8:00 am EDT/2:00 pm SAST Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie, Presiding Bishop, 10th Episcopal District, Program Chair 51st Quadrennial Session, General Conference, Preaching THE EPISCOPAL ADDRESS Tuesday, July 6, 2021 4:25 pm EDT/10:25 pm SAST Bishop Gregory G.M. Ingram, Presiding Bishop, 1st Episcopal District Registered Agent and Chairman, Board of Trustees, African Methodist Episcopal Church THE AME HBCU NIGHT Tuesday, July 6, 2021 6:45 PM EDT/12:45 am SAST *Replay Wednesday, July 7, 2021, 11:00 am SAST Bishop Wilfred J. Messiah, President of the General Board, Presiding Bishop, 17th Episcopal District, Meditation Dr. Michael Sorrell, President, Paul Quinn College, Dallas, Texas, Impact of AME HBCU Schools J. J. Hairston, Gospel Artist Amplifying 14 AME Colleges, Universities and Seminaries 1 THE MEMORIAL SERVICE Thursday, July 8, 2021 2:45 pm EDT/8: 45 pm SAST Bishop Stafford J. N. Wicker, Presiding Bishop, 18th Episcopal District, Presiding THE SERVICE OF WORD AND SACRAMENT Thursday, July 8, 2021 3:30 pm EDT/9:30 pm SAST Bishop Samuel L. Green, Sr., Presiding Bishop, 7th Episcopal District, Preaching THE RETIREMENT SERVICE FOR GENERAL OFFICERS AND BISHOPS Friday, July 9, 2021 3:10 pm EDT/9:10 pm SAST Bishop James L. -

John Wesley's Concept of the Church 9 with the Church of England

John Wesley s Concept of the Church Reginald Kissack Few theological issues today are more alive than those which concern the nature of the Christian Church. If one could superimpose the various notions of the various churches, the first impression would be surprise at the extent of the area common to all, and the next greater perplexity at the tenacity with which each upholds the importance of its particular margin. Yet even here the gradations of difference would follow a fairly simple pattern of development. The "right-wing" "Catho lic" concepts shade through the older Reformation churches into the "independent" churches, following a fairly regular historical development, with Quakers and the Salvation Army, despite their rejection of sacramental ideas, and the very name of Church, seen to be quite clearly a part of the system for all that are at the extreme left. It would be seen that by far the greatest controversy turns on the concept of ministry, with only slightly less dispute about the relation of Scriptures to the Church. Towards the left of the scale, spirit of Christ rather than body of Christ seems to define the relation of the Church to its Lord; accordingly the sacramental notion fades away. Whereas all parts of the scale regard holiness as an essential element, there are many differ ent notions about what it consists in. On the right it seems to be a sacramental right relationship with the institution of the Church; it shades through ideas that equate it with right doctrine , into a personal standard of outward behavior . -

African American Methodism in the M. E. Tradition: the Case of Sharp Street (Baltimore)

The North Star: A Journal of African American Religious History (ISSN: 1094-902X ) Volume 8, Number 2 (Spring 2005) African American Methodism in the M. E. Tradition: The Case of Sharp Street (Baltimore) J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion ©2005 J. Gordon Melton. Any archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text in any medium requires the consent of the author. The role of African Americans in the The life and role of Black Methodists, Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) in the however, were rarely considered in such decades prior to the Civil War remains on of discussions. The subsequent attempts to the most neglected areas of African discuss Black ME Methodists were largely American religious studies. This neglect has limited to celebrating the careers of several persisted in spite of the fact that the MEC preachers—Harry Hosier, John Charleston, was the largest denomination among Henry Evans, John Stewart. Only in the last America's several religious communities decade has some effort to move beyond this during these years and included in its situation been made.2 Thus all the questions membership more African Americans than remain—why did the majority of African any other group. The problem became Americans who identified themselves as evident as the new discipline of African Methodists remain in the MEC through the American religious studies appeared in the Antebellum Period, rather than join one of 1960s. Significant studies had and were the several independent Black appearing concerning white attitudes toward denominations? What were the issues that African Americans and the changing split the Black Methodist community into positions of Methodists regarding slavery.1 four groups, especially what issues divided those that left the MEC and those that stayed? What role did Black Methodists play 1 Cf. -

Workbook Reports

1 WELCOME AND GREETINGS FROM OUR BISHOP 2 3 Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, 4 Welcome to the second consecutive virtual annual session of the 5 Florida Conference! We live in an unprecedented season. COVID has 6 changed how we work, gather, travel, eat meals, worship, see our 7 families and friends. As I write we acknowledge that over 500,000 8 Americans and 30,000 Floridians have died of COVID. Lord, in your 9 mercy, hear our prayers! 10 11 We join together during these days as disciples of Jesus Christ and 12 leaders in his mission (Matthew 22 and 28). We will also do the work 13 of our annual conference which is focused on three commitments: vital and sustainable local 14 churches, the journey toward antiracism as an expression of discipleship, and the health and 15 resilience of clergy. 16 This year’s Annual Conference theme is “A Community of Love and Forgiveness”, which is a 17 phrase taken from our liturgy of baptism when we welcome new persons into our churches. In a 18 world beset by multiple pandemics and many challenges, this can be a source of guidance and 19 purpose in our time together. 20 21 Our conference will be marked by music and worship, study and prayer, debate and conferencing, 22 business and visioning. We will commission and ordain men and women for set apart leadership 23 in the church. We will send clergy into congregational and extension leadership for the coming 24 year. We will make important decisions as an Annual Conference around the vital mission of our 25 church, especially in this season of disruption. -

Scouting in the African Methodist Episcopal Church

Scouting In The African Methodist Episcopal Church Background • The African Methodist Episcopal Church, A.M.E. for short, was the first church in the United States to be made up entirely of African Americans. o The church began in 1787 in Philadelphia when African Americans refused to be segregated in the seating at St. George’s Church on Fourth Street. o The church was established in 1816 in Philadelphia when Richard Allen was consecrated as its first bishop. • According to the 2010 Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches, there are 2.5 million members of the African Methodist Episcopal church. • The mission of the A.M.E. church is to minister to the spiritual, intellectual, physical, emotional, and environmental needs of all people by spreading Christ’s liberating gospel through the word and deeds. • The motto of the A.M.E. church is God our Father, Christ our Redeemer, the Holy Spirit our Comforter, Humankind our Family. • At the end of 2010, the A.M.E.’s use of Scouting included: o 1,647 Cub Scouts in 85 packs o 789 Boy Scouts in 71 troops o 96 Venturers in seven crews Association of African Methodist Episcopal Scouts Founded in 1993, the Association of African Methodist Episcopal Scouts (AAMES) works to encourage and support A.M.E. congregations with their youth ministries through the use of established programs such as the Boy Scouts of America. Scouting is encouraged to be incorporated into A.M.E. Christian education programs for youth leadership and community outreach by: • Fostering religious growth through religious awards programs, such as the God and Country Award Program and the A.M.E. -

Bishop's Parliamentary Ruling on Resolution #2021-6

Bishop’s Parliamentary Ruling on Resolution #2021‐6 “Vote on Which Post‐separation Church to Join” Michigan Annual Conference, United Methodist Church Bishop David Alan Bard June 5, 2021 Given that resolution 2021‐6 was rejected by the legislative committee, normally we would move directly to a vote to see if 20% of you wanted to bring this to the plenary for discussion and action. That is what will happen with two resolutions yet to come. However, anticipating that I would be asked to consider a point of order as to whether this resolution is in order to be considered by the annual conference during this plenary session – anticipating this because I have been asked about it numerous times already, and knowing that a presiding officer can raise a question of order on their own accord (Robert’s Rules of Order, p. 268, 11th edition, see also p. 113), I will be ruling this resolution out of order for the following reasons. The primary reason this resolution is out of order is found in its title, “vote on which post‐ separation Church to join.” An annual conference does not have the authority to vote to leave the United Methodist Church. Such authority may be given it if the General Conference were to enact a resolution such as the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace Through Separation, but it does not have such authority now. The Protocol would not be a change in the Book of Discipline but an extra‐disciplinary agreement on separation granting annual conferences such authority for a limited period of time. -

Methodist Heritage”

Holy Christmas – Day 11 Monday before Epiphany January 4, 2021 “Methodist Heritage” In the closing days of Christmas I find myself reflecting on my heritage as a United Methodist ordained Elder and Deacon, a retired member of the West Virginia Annual Conference. This new year of 2021 brings many concerns about what The United Methodist Church will look like going forward. This will be a critical year for people called Methodists. These are challenging days to be the Church in midst of world-wide pandemic. Every United Methodist clergyperson and lay leadership uses (and should have in their library) the books – The Holy Scriptures, UM Book of Worship, The UM Hymnal, Book of Discipline, Book of Resolutions and the Conference Journal. Each of these represents the various aspects of engaging in ministry through the teachings of The United Methodist Church. They guide, inform, govern, challenge and inspire as we carry out the mission of The United Methodist Church – “to make disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world.” During the season of Christmas we United Methodist people reflect and remember the beginnings of Methodism in America out of our Wesleyan heritage in The Church of England. The “Christmas Conference of 1784” was the beginning of the Church. I like the summary notes of the meeting as shared by Dr. Bertrand M. Tipple, Methodist preacher, writer & lecturer: “On Friday morning, December 24 the party . .traveled to Baltimore, and the first session of the Christmas Conference began at ten o’clock in Lovely Lane Meeting House. Thomas Coke presided as John Wesley’s representative and presented the plan.