Methodist-History-2011-04-Bishop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Wesley and the Principle of Ministerial Succession

John Wesley and the Principle of Ministerial Succession By John C. English + SUBJECT of recurring interest among Methodists is John A Wtesley's doctrine of the ministry. Succeeding generations of students have sought to derive from the ambiguous evidence a historically accurate picture of Wesley's thought on this subject. The defense of Wesley's setting apart a ministry for the Methodists in America and the British Isl'es is a staple in Methodist apologetic. Today, when many Christians from all denominations are discuss- ing the reunion of the churches, the question of the Wesleyan un- derstanding of the ministry has taken on additional significance. A common interpretation of Wesley's teaching concerning the ministry has not emerged from the extensive discussion of the question. Why is this the case? Ernst Troeltsch, in his famous book, The Social Teaching of the Christian Churches, introduces a distinction between two types of Christianity, "sect" and "church." Representatives of these types differ, among other things, in their interpretation of the ministry. In the "sect" ministerial functions are usually exercised by laymen. "Sectarians" emphasize the pneumatic and prophetic aspects of the ministry. "Churchmen," on the other hand, stress the hierarchical and -priestly - elements in th,e ministerial office. This emphasis- reflects their sacramentalist understanding of the Christian religion. By and large- students of Wesley have interpreted his doctrine of the ministry in (6 sectarian" terms. certainly one may find in Wesley's actions and writings a considerable amount of support for such a view. Many statements by Wesley, however, cannot be fitted easily into this interpretation. -

And Greetings from Our Bishop

WELCOME AND GREETINGS FROM OUR BISHOP Dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ, Welcome to the annual session of the Florida Conference of the United Methodist Church. We join together during these days as disciples of Jesus Christ and leaders in his mission. This year we will celebrate our calling to be “On Mission Together,” and our vision to cultivate courageous leadership, missional engagement and spirit-led innovation. Our conference will be marked by music and worship, study and prayer, debate and conferencing, fellowship and laughter, business and visioning. We will license, commission and ordain men and women for set apart leadership in the church. We will send clergy into congregational and extension leadership for the coming year. We will elect laity and clergy delegates to the 2020 General Conference. We will celebrate extraordinary faithfulness in response to natural disasters in our region, and we will process the outcomes of the recent Special Session of the 2019 General Conference. And we will return to our local churches, more aware of our connection as Florida United Methodists. Gathering at Florida Southern College in Lakeland, the Annual Conference will begin with the celebration of Holy Communion. Our keynote speakers will be extraordinary: Bishop Will Willimon of Duke Divinity School will be our conference preacher, and Dr. Dana Robert of Boston University will be our teacher. Dr. Gary Spencer will preach the memorial sermon and Dr. Cynthia Weems, dean of the cabinet, will give the cabinet’s report. Inspirational music will be led by Jarvis Wilson and Keith Wilson of Atlanta, Georgia. Our offerings will support the re-development of the Wesley Foundation at Florida A & M University, and the launch of a new church inside Lowell Women’s Prison in Reddick. -

F:(T/("J~/ R PROCEEDINGS

f:(t/("J~/ r PROCEEDINGS. THE RECENT DISCOVERIES OF W ESLEY JV\55. AT THE BooK ROOJY\. The Standard Edition of Wesley's Journal could scarcely have reached its present stage of comparative completeness but for discoveries. Ancient notebooks, letters yellow with age, a few choice men with leisure and inclination to read them and with knowledge of the niches into which they naturally fit, were found. Yet, as some would argue, the books and papers had never been actually lost. By sale, gift or marriage, they had passed from hand to hand, very often the hands belonging to heads that neither understood nor cared for such things, except as curiosities, which, like inscribed stones and Worcester china, were gaining money-value by age. But just because they were old and once belonged to men of note, they were securely guarded in strong rooms, Chubb's safes, or women's treasure-boxes. They were "lost" in "safe places." I once held in my hand a printed book, now fabulously valuable, which when shown to me had risen in price from two-pence to a hundred pounds. It was " found" on a street-barrow by a man who had eyes to see. But of the hundreds of Wesley MSS. which have passed through my hands not one, so far as I know, was ever "lost " in the book-barrow sense. Someone has always known of its existence, though perhaps for fifty or a hundred years no one has realised its intrinsic importance. This is true of nearly if not quite all of the Wesley MSS. -

The Magazine of Vanderbilt University's College of Arts

artsandS CIENCE The magazine of Vanderbilt University’s College of Arts and Science F A L L 2 0 0 9 spring2008 artsANDSCIENCE 1 whereAER YOU? tableOFCONTENTS FALL 2009 20 12 6 30 6 Opportunity Vanderbilt departments Two of Vanderbilt’s volunteer leaders discuss the expanded financial aid initiative. A View from Kirkland Hall 2 Arts and Science Notebook 3 8 2 1 Arts and Science in the World A Middle Eastern Calling Five Minutes With… 10 Leor Halevi exercises his imagination and love of history in the study of Islam. Up Close 14 Great Minds 16 0 2 Passion Wins Out Rigor and Relevance 18 Open Book 25 Studying what they love is the path to career success for Arts and Science alumni. And the Award Goes To 26 Forum 30 8 2 The NBA’s International Playmaker First Person 32 Basketball’s global growth and marketing opportunities thrive under alumna Giving 34 Heidi Ueberroth’s leadership. College Cabinet 36 In Place 44 NEIL BRAKE Parting Shot 46 artsANDC S IENCE© is published by the College of Arts and Science at Vanderbilt University in cooperation with the Office of Development and Alumni Relations Communications. You may contact the editor by e-mail at [email protected] or by U.S. mail at PMB 407703, 2301 Vanderbilt Place, Nashville, TN 37240-7703. Editorial offices are located in the Loews Vanderbilt Office Complex, 2100 West End Ave., Suite 820, Nashville, TN 37203. Nancy Wise, EDITOR Donna Pritchett, ART DIRECTOR Jenni Ohnstad, DESIGNER Neil Brake, Daniel Dubois, Steve Green, Jenny Mandeville, John Russell, PHOTOGRAPHY Lacy Tite, WEB EDITION Nelson Bryan, BA’73, Mardy Fones, Tim Ghianni, Miron Klimkowski, Craig S. -

Bishop J. W. Alstork, We Need to Impress Upon the White D.D., LLD

= Bishop J. W. Alstork, We need to impress upon the white D.D., LLD. people the fact that there are thou sands who are reaching out for better A. 1'1. E. Zioll Church living, for clean living, and that they Reaidellce: l'Iolltiomery. Alabama ought to be encouraged in this desire l.hSHOP AI.STOHK presiCles over the Ala and conduct. In a certain city, houses bama, Florida. and Mississippi conferences. of ill-repute are put in a section where He wus born in Talludegll, Ala., September some of the best colored people live, I, 1852. He studied lit night schools and and where their children are compelled worked on the railroad during the day as brakeman, baggageman, warehouse mun, to gaze upon the obscenity of this lewd cotton marker, and smnpler. Later, he class of white people, and cannot help attended Talladegu ollege und then tuught themselves. When the mayor of the city school. was appealed to, he said to the com He WllS cnIled to the ministry in 1878, and plainant, "H you do not like it, you after completing his theological course, in 1882, was appointed to some of the strong can sell out and move to another part churches of the denomination. He was of the town." financial secretary for his conference for eight H it were not for a few white friends years, and was then elected financial secretary we have, I don't know what would be for the entire connection, in which position come of us. It would help wonderfully, he served eight years. -

![Anderson, James Douglas (1867-1948) Papers 1854-[1888-1948]-1951](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7591/anderson-james-douglas-1867-1948-papers-1854-1888-1948-1951-1467591.webp)

Anderson, James Douglas (1867-1948) Papers 1854-[1888-1948]-1951

ANDERSON, JAMES DOUGLAS (1867-1948) PAPERS 1854-[1888-1948]-1951 (THS Collection) Processed by: John H. Thweatt & Sara Jane Harwell Archival Technical Services Date completed: December 15, 1976 Location: THS III-B-1-3 THS Accession Number: 379 Microfilm Accession Number: 610 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION This collection is centered around James Douglas Anderson (1867-1948), journalist, lawyer, and writer of Madison, Davidson County, Tennessee. The papers were given to the Tennessee Historical Society by James Douglas Anderson and his heirs. They are the property of the Tennessee Historical Society and are held in the custody and under the administration of the Tennessee State Library and Archives (TSLA). Single photocopies of the unpublished writings in the James Douglas Anderson Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research and are obtainable from the TSLA upon payment of a standard copying fee. Possession of photocopy does not convey permission to publish. If you contemplate publication of any such writings, or any part or excerpt of such writings, please pay close attention to and be guided by the following conditions: 1. You, the user, are responsible for finding the owner of literary property right or copyright to any materials you wish to publish, and for securing the owner's permission to do so. Neither the Tennessee State Library nor the Tennessee Historical Society will act as agent or facilitator for this purpose. 2. When quoting from or when reproducing any of these materials for publication or in a research paper, please use the following form of citation, which will permit others to locate your sources easily: James Douglas Anderson Papers, collection of the Tennessee Historical Society, Tennessee State Library and Archives, box number_____, folder number____. -

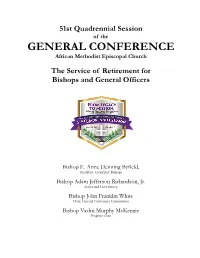

General-Conference-REVISED-Service-Of-Retirement-2021-07-05

51st Quadrennial Session of the GENERAL CONFERENCE African Methodist Episcopal Church The Service of Retirement for Bishops and General Officers Bishop E. Anne Henning Byfield, President, Council of Bishops Bishop Adam Jefferson Richardson, Jr. Senior and Host Bishop Bishop John Franklin White Chair, General Conference Commission Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie Program Chair The Service of Retirement for Bishops and General Officers IN OBSERVANCE OF The Fifty-first Quadrennial Session of the General Conference African Methodist Episcopal Church Orange County Convention Center Orlando, Florida Friday, The Ninth Day of July Two Thousand Twenty-One 3:10 – 4:00 pm EDT 9:10 – 10:00 pm SAST The Order of Service Bishop Adam J. Richardson, Jr. Worship Leader The Moments of Praise The Call to Worship Bishop Adam J. Richardson, Jr. Bishop: The Bible instructs us to give honor to those to whom honor is due. Today we gather to pay tribute to two Bishops and four General Officers for their years of service and labors of love in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. We salute them for a job well done. People: For them, O God, we give Thee thanks. Bishop: We thank you, O God, for their strength to bear burdens and their grace to share blessings. People: For them, O God, we give Thee thanks. Bishop: For their ministries, sacrifices, lives touched, services rendered, and sermons preached, People: For them, O God, we give Thee thanks. Bishop: For the sixty-nine collecJve years of Episcopal Service given by Bishops McKinley Young, VashJ Murphy McKenzie, and Gregory Gerald McKinley Ingram, we praise God for them. -

The Foreign Minister of Methodism

The Foreign Minister of Methodism By Warren Thomas Smith Saturday, September 18, 1784, may have dawned as just another day in Bristol, England, but in the province of God it was highly significant. “At ten in the morning we sailed from King—Road for New York. A breeze soon sprung up, which carried us with the help of the tides, about a hundred leagues from Bristol by Monday morning . .” so Thomas Coke made the first entry in his Journal, a little volume published in 1793 and dedicated to John Wesley. The small vessel was not unlike other ships of the time, yet it was playing a role in an important scene of church history. Three of the passengers were to open a new chapter in the religious life of America. Of these one was a dedicated Welsh gentleman who would travel at least a hundred thousand miles on a hundred separate voyages as the Foreign Minister of Methodism and Ambassador of Jesus Christ. Thomas Coke was sailing as the executor of John Wesley’s design for the people called Methodists. It is doubtful that this plump little clergyman, who stood just five feet one inch, fully realized the significance of the voyage he was undertaking. A church was about to be born, and he was to be a key figure in the first moment of its breathing. Background of the Time We cannot form an estimate of the life and work of Thomas Coke without considering the time-spirit in which he lived: (1) His was to be a background of war and threat of war. -

Jean & Alexander Heard Libraries

Jean & Alexander Heard Libraries 2018–19 VANDERBILT From the University Librarian The Expanding Role of Libraries in the Research Life Cycle Libraries have technologies have advanced, the role of the libraries always been the first has grown and now touches nearly every phase in the place a researcher research life cycle. For example, Vanderbilt’s librarians goes when starting not only provide advice on such things as search a project. Library strategies or resources, but also partner with scholars resources naturally in areas where specialized skills are needed, such as stand near the data management, GIS, provenance research, digital beginning of the visualization and preservation, or dataset retrieval and research life cycle storage. The libraries are also involved in publishing that includes and encouraging open access of research results (see hypotheses or ideas, the story on new library journals and see vanderbi.lt/ SUSAN URMY SUSAN scholarship review, staffscholarship for librarians’ research). data collection, analysis and assessment. And libraries play a role after With the help of the libraries, students are publishing as well by acquiring the research for our transformed into scholars. Librarians work with collections and contributing to its dissemination. faculty, but also with first-year students (see VUceptor At Vanderbilt, the role of the libraries in the research story), with students as they declare a major (Personal life cycle has expanded to include a broad array of Librarians), and with graduate students at every collections and services from data analysis tools level (New Study Spaces). Vanderbilt’s librarians are to open access publishing. The skill sets of our in classrooms and labs, and on course websites; we librarians are also evolving to meet the needs of work with faculty on campus and around the world; students and faculty. -

2021 Preacher Itinerary

51st Quadrennial Session of the GENERAL CONFERENCE African Methodist Episcopal Church Bishop E. Anne Henning Byfield President, Council of Bishops Bishop Adam Jefferson Richardson, Jr. Senior and Host Bishop Bishop John Franklin White Chair, General Conference Commission Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie Program Chair PROCLAIMERS OF THE GOSPEL THE OPENING WORSHP SERVICE Tuesday, July 6, 2021 8:00 am EDT/2:00 pm SAST Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie, Presiding Bishop, 10th Episcopal District, Program Chair 51st Quadrennial Session, General Conference, Preaching THE EPISCOPAL ADDRESS Tuesday, July 6, 2021 4:25 pm EDT/10:25 pm SAST Bishop Gregory G.M. Ingram, Presiding Bishop, 1st Episcopal District Registered Agent and Chairman, Board of Trustees, African Methodist Episcopal Church THE AME HBCU NIGHT Tuesday, July 6, 2021 6:45 PM EDT/12:45 am SAST *Replay Wednesday, July 7, 2021, 11:00 am SAST Bishop Wilfred J. Messiah, President of the General Board, Presiding Bishop, 17th Episcopal District, Meditation Dr. Michael Sorrell, President, Paul Quinn College, Dallas, Texas, Impact of AME HBCU Schools J. J. Hairston, Gospel Artist Amplifying 14 AME Colleges, Universities and Seminaries 1 THE MEMORIAL SERVICE Thursday, July 8, 2021 2:45 pm EDT/8: 45 pm SAST Bishop Stafford J. N. Wicker, Presiding Bishop, 18th Episcopal District, Presiding THE SERVICE OF WORD AND SACRAMENT Thursday, July 8, 2021 3:30 pm EDT/9:30 pm SAST Bishop Samuel L. Green, Sr., Presiding Bishop, 7th Episcopal District, Preaching THE RETIREMENT SERVICE FOR GENERAL OFFICERS AND BISHOPS Friday, July 9, 2021 3:10 pm EDT/9:10 pm SAST Bishop James L. -

John Wesley's Concept of the Church 9 with the Church of England

John Wesley s Concept of the Church Reginald Kissack Few theological issues today are more alive than those which concern the nature of the Christian Church. If one could superimpose the various notions of the various churches, the first impression would be surprise at the extent of the area common to all, and the next greater perplexity at the tenacity with which each upholds the importance of its particular margin. Yet even here the gradations of difference would follow a fairly simple pattern of development. The "right-wing" "Catho lic" concepts shade through the older Reformation churches into the "independent" churches, following a fairly regular historical development, with Quakers and the Salvation Army, despite their rejection of sacramental ideas, and the very name of Church, seen to be quite clearly a part of the system for all that are at the extreme left. It would be seen that by far the greatest controversy turns on the concept of ministry, with only slightly less dispute about the relation of Scriptures to the Church. Towards the left of the scale, spirit of Christ rather than body of Christ seems to define the relation of the Church to its Lord; accordingly the sacramental notion fades away. Whereas all parts of the scale regard holiness as an essential element, there are many differ ent notions about what it consists in. On the right it seems to be a sacramental right relationship with the institution of the Church; it shades through ideas that equate it with right doctrine , into a personal standard of outward behavior . -

African American Methodism in the M. E. Tradition: the Case of Sharp Street (Baltimore)

The North Star: A Journal of African American Religious History (ISSN: 1094-902X ) Volume 8, Number 2 (Spring 2005) African American Methodism in the M. E. Tradition: The Case of Sharp Street (Baltimore) J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion ©2005 J. Gordon Melton. Any archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text in any medium requires the consent of the author. The role of African Americans in the The life and role of Black Methodists, Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) in the however, were rarely considered in such decades prior to the Civil War remains on of discussions. The subsequent attempts to the most neglected areas of African discuss Black ME Methodists were largely American religious studies. This neglect has limited to celebrating the careers of several persisted in spite of the fact that the MEC preachers—Harry Hosier, John Charleston, was the largest denomination among Henry Evans, John Stewart. Only in the last America's several religious communities decade has some effort to move beyond this during these years and included in its situation been made.2 Thus all the questions membership more African Americans than remain—why did the majority of African any other group. The problem became Americans who identified themselves as evident as the new discipline of African Methodists remain in the MEC through the American religious studies appeared in the Antebellum Period, rather than join one of 1960s. Significant studies had and were the several independent Black appearing concerning white attitudes toward denominations? What were the issues that African Americans and the changing split the Black Methodist community into positions of Methodists regarding slavery.1 four groups, especially what issues divided those that left the MEC and those that stayed? What role did Black Methodists play 1 Cf.