Charles Darwin University the Maubara Fort, a Relic of Eighteenth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Van Tekst

Dietsche Warande. Nieuwe reeks. Deel 3 bron Dietsche Warande. Nieuwe reeks. Deel 3. C.L. van Langenhuysen, Amsterdam 1881 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_die003188101_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl i.s.m. V Inhoud. Blz. BILDERDIJK, door P.F.TH. VAN HOOGSTRATEN (VI, VII) 1, 440 VONDEL IN ZIJN ‘BESPIEGELINGEN’, door P.F.J.V. DE GROOT, (Slot) 23 DE ILIAS VAN HOMEROS, door P.F.TH. VAN HOOGSTRATEN 44 DE HEEREN VAN HALEWIJN, Markiezen van Peene, eene genealogische bijdrage 53 van A.B.J. STERCK ADRIAAN WILLEM BARON VAN RENESSE, voorlaatste abt van Sinte Geertruide te 81, Leuven, door ED. VAN EVEN 168 EENE WANHOPIGE ‘LEVENSBESCHOUWING’. Lilith, Gedicht in drie zangen, van 97 MARCELLUS EMANTS, door A.TH. REINIER CRAEYVANGER, door A.TH. 125 HET HOLLANDSCH BLOED VAN ALBERT GRAAF DE MUN, door H.J. ALLARD 129 ANTIEKE BEELDEN. ‘Frauengestalten’ van Mevr. Schneider, door A.TH. 142 ONUITGEGEVEN VAERZEN van MR. W. BILDERDIJK 147 e MONUMENTALE SCHILDERKUNST, Makarts ‘Intocht van Karel den V ’, door A.TH. 187 r EENIGE TREKKEN UIT DE GESCHIEDENIS DER BESCHAVING VAN BELGIË door Prof. D 201 P.P.M. ALBERDINGK THIJM. ONUITGEGEVEN DICHTSTUK [van Dirck Rz. Camphuysen?] medegedeeld door J.F. 220 VAN SOMEREN JOANNES MURMELLIUS, een Nederlandsch Humanist, door W. WESSELS 223 PIAE MEMORIAE G.W. VREEDE, door J.W SPIN 289 GESLACHTLIJST DER FAMILIE HOOFT, door J.A.ALB.TH. 252 Dietsche Warande. Nieuwe reeks. Deel 3 VI Blz. EEN LETTERKUNDIG EEUWFEEST, 16 Maart 1581-16 Maart 313 1881, door Dr. JAN TEN BRINK SUSANNE BARTELOTTI, Komedie, in twee Bedrijven, door 327 J.A.A.TH. -

Hoge Regering Inventaris Van Het Archief Van De Gouverneur-Generaal En Raden Van Indië

Nummer Toegang: Hoge Regering Inventaris van het archief van de gouverneur-generaal en raden van Indië (Hoge Regering) van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie en taakopvolgers, 1612-1812 Louisa Balk en Frans van Dijk, medewerkenden: mw. Dra. Dwi Mudalsih, mw. Dwi Nurmaningsih, mw. Dra. Esti Kartikaningsih, mw. Dra. Euis Shariasih, mw. Isye Djumenar, mw. Iyos Rosidah, mw. Dra. Kris Hapsari, hr. Drs. Langgeng Solistyo Budi, mw. Mira Puspita Rini, mw. Drs. Risma Manurung, mw. Sutiasni, mw. Triana Widyaningrum, hr. Drs. Sunarto, hr. Syarif Usman en mw. Dra. Widiyanti Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, Jakarta (c) 2002 This finding aid is written in Dutch. Hoge Regering 3 INHOUDSOPGAVE BESCHRIJVING VAN HET ARCHIEF INHOUD EN STRUCTUUR VAN HET ARCHIEF ................ 7 Aanwijzingen voor de gebruiker ............................................................................. 9 Openbaarheidsbeperkingen ...................................................................................9 Beperkingen aan het gebruik .................................................................................9 Materiële beperkingen ..........................................................................................9 Aanvraaginstructie ...............................................................................................9 Citeerinstructie ....................................................................................................9 Archiefvorming ................................................................................................... -

Gouverneur-Generaals Van Nederlands-Indië in Beeld

JIM VAN DER MEER MOHR Gouverneur-generaals van Nederlands-Indië in beeld In dit artikel worden de penningen beschreven die de afgelo- pen eeuwen zijn geproduceerd over de gouverneur-generaals van Nederlands-Indië. Maar liefs acht penningen zijn er geslagen over Bij het samenstellen van het overzicht heb ik de nu zo verguisde gouverneur-generaal (GG) voor de volledigheid een lijst gemaakt van alle Jan Pieterszoon Coen. In zijn tijd kreeg hij geen GG’s en daarin aangegeven met wie er penningen erepenning of eremedaille, maar wel zes in de in relatie gebracht kunnen worden. Het zijn vorige eeuw en al in 1893 werd er een penning uiteindelijk 24 van de 67 GG’s (niet meegeteld zijn uitgegeven ter gelegenheid van de onthulling van de luitenant-generaals uit de Engelse tijd), die in het standbeeld in Hoorn. In hetzelfde jaar prijkte hun tijd of ervoor of erna met één of meerdere zijn beeltenis op de keerzijde van een prijspen- penningen zijn geëerd. Bij de samenstelling van ning die is geslagen voor schietwedstrijden in dit overzicht heb ik ervoor gekozen ook pennin- Den Haag. Hoe kan het beeld dat wij van iemand gen op te nemen waarin GG’s worden genoemd, hebben kantelen. Maar tegelijkertijd is het goed zoals overlijdenspenningen van echtgenotes en erbij stil te staan dat er in andere tijden anders penningen die ter gelegenheid van een andere naar personen en functionarissen werd gekeken. functie of gelegenheid dan het GG-schap zijn Ik wil hier geen oordeel uitspreken over het al dan geslagen, zoals die over Dirck Fock. In dit artikel niet juiste perspectief dat iedere tijd op een voor- zal ik aan de hand van het overzicht stilstaan bij val of iemand kan hebben. -

De Tijgersgracht Te Batavia

DE TIJGERSGRACHT TE BATAVIA. DOOR S. KALFF. Thans moet men ze zoeken, de voornaamste, de deftigste gracht van het oude Batavia, maar in de dagen van de loffelijke Compagnie was zij een slagader van het verkeer, de wijk der notabelen bij uitnemendheid, door dichters bezongen en door schilders, althans door teekenaars „affgeconterfeit." 't Was geenszins toeval dat de hoofdgrachten der stad meerendeels gedoopt waren met namen, aan de tropische dierwereld ontleend. Er was een Kaaimans-, een Leeuwinne-, een Rhinocer-, een Tijgersgracht, met nog een Buffelsrivier, Plattegrond van Batavia met het kasteel. verbonden door ettelijke dwarsgrachten. Batavia was eene stad naar vader- landsch model aangelegd en de rivier waaraan zij gelegen was, de Groote Rivier, maakte zelve, tusschen gemetselde beschoeiingen ingeklemd, de voor- naamste gracht uit. Uit deze van de Blauwe Bergen afstroomende Tjiliwong had de waterver- deeling plaats in het net van zestien grachten, waarmede het college van heemraden de hoofdstad in den loop der jaren begiftigd had. In later dagen zou Batavia, wat den plattegrond en de bouworde harer huizen betreft, wel eens een tweede uitgaaf van Amsterdam genoemd worden, doch de slingerende DE TIJGERSGRACHT TË BATAVIA. 445 stroomlijn der Amsterdamsche grachten werd hier gemist. De Bataviaasche, met uitzondering van de Ringgracht om het Kasteel, sneden elkander recht- hoekig en verdeelden over 't geheel de stad in paralellogrammen, die waarlijk wel den tooi der boomenreien langs hunne zoomen behoefden om het oog eenigszins tevreden te stellen. De stad was gebouwd op een alluviaal en moerassig terrein, en, eenmaal die plaats gekozen, was het natuurlijk dat men door een samenstel van grachten en vaarten den weeken grond trachtte te draineeren en tevens in het verkeer te water te voorzien. -

Trajectories of the Early-Modern Kingdoms in Eastern Indonesia: Comparative Perspectives

Trajectories of the early-modern kingdoms in eastern Indonesia: Comparative perspectives Hans Hägerdal Introduction The king grew increasingly powerful. His courage indeed resembled that of a lion. He wisely attracted the hearts of the people. The king was a brave man who was sakti and superior in warfare. In fact King Waturenggong was like the god Vishnu, at times having four arms. The arms held the cakra, the club, si Nandaka, and si Pañcajania. How should this be understood? The keris Ki Lobar and Titinggi were like the club and cakra of the king. Ki Tandalanglang and Ki Bangawan Canggu were like Sangka Pañcajania and the keris si Nandaka; all were the weapons of the god Vishnu which were very successful in defeating ferocious enemies. The permanent force of the king was called Dulang Mangap and were 1,600 strong. Like Kalantaka it was led by Kriyan Patih Ularan who was like Kalamretiu. It was dispatched to crush Dalem Juru [king of Blambangan] since Dalem Juru did not agree to pass over his daughter Ni Bas […] All the lands submitted, no-one was the equal to the king in terms of bravery. They were all ruled by him: Nusa Penida, Sasak, Sumbawa, and especially Bali. Blambangan until Puger had also been subjugated, all was lorded by him. Only Pasuruan and Mataram were not yet [subjugated]. These lands were the enemies (Warna 1986: 78, 84). Thus did a Balinese chronicler recall the deeds of a sixteenth-century ruler who supposedly built up a mini-empire that stretched from East Java to Sumbawa. -

8Th Euroseas Conference Vienna, 11–14 August 2015

book of abstracts 8th EuroSEAS Conference Vienna, 11–14 August 2015 http://www.euroseas2015.org contents keynotes 3 round tables 4 film programme 5 panels I. Southeast Asian Studies Past and Present 9 II. Early And (Post)Colonial Histories 11 III. (Trans)Regional Politics 27 IV. Democratization, Local Politics and Ethnicity 38 V. Mobilities, Migration and Translocal Networking 51 VI. (New) Media and Modernities 65 VII. Gender, Youth and the Body 76 VIII. Societal Challenges, Inequality and Conflicts 87 IX. Urban, Rural and Border Dynamics 102 X. Religions in Focus 123 XI. Art, Literature and Music 138 XII. Cultural Heritage and Museum Representations 149 XIII. Natural Resources, the Environment and Costumary Governance 167 XIV. Mixed Panels 189 euroseas 2015 . book of abstracts 3 keynotes Alarms of an Old Alarmist Benedict Anderson Have students of SE Asia become too timid? For example, do young researchers avoid studying the power of the Catholic Hierarchy in the Philippines, the military in Indonesia, and in Bangkok monarchy? Do sociologists and anthropologists fail to write studies of the rising ‘middle classes’ out of boredom or disgust? Who is eager to research the very dangerous drug mafias all over the place? How many track the spread of Western European, Russian, and American arms of all types into SE Asia and the consequences thereof? On the other side, is timidity a part of the decay of European and American universities? Bureaucratic intervention to bind students to work on what their state think is central (Terrorism/Islam)? -

Length-Based Stock Assessment Area WPP

Report Code: AR_711_120820 Length-Based Stock Assessment Of A Species Complex In Deepwater Demersal Fisheries Targeting Snappers In Indonesia Fishery Management Area WPP 711 DRAFT - NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION. TNC-IFCP Technical Paper Peter J. Mous, Wawan B. IGede, Jos S. Pet AUGUST 12, 2020 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY INDONESIA FISHERIES CONSERVATION PROGRAM AR_711_120820 The Nature Conservancy Indonesia Fisheries Conservation Program Ikat Plaza Building - Blok L Jalan By Pass Ngurah Rai No.505, Pemogan, Denpasar Selatan Denpasar 80221 Bali, Indonesia Ph. +62-361-244524 People and Nature Consulting International Grahalia Tiying Gading 18 - Suite 2 Jalan Tukad Pancoran, Panjer, Denpasar Selatan Denpasar 80225 Bali, Indonesia 1 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY INDONESIA FISHERIES CONSERVATION PROGRAM AR_711_120820 Table of contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Materials and methods for data collection, analysis and reporting 6 2.1 Frame Survey . 6 2.2 Vessel Tracking and CODRS . 6 2.3 Data Quality Control . 7 2.4 Length-Frequency Distributions, CpUE, and Total Catch . 7 2.5 I-Fish Community . 28 3 Fishing grounds and traceability 32 4 Length-based assessments of Top 20 most abundant species in CODRS samples includ- ing all years in WPP 711 36 5 Discussion and conclusions 79 6 References 86 2 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY INDONESIA FISHERIES CONSERVATION PROGRAM AR_711_120820 1 Introduction This report presents a length-based assessment of multi-species and multi gear demersal fisheries targeting snappers, groupers, emperors and grunts in fisheries management area (WPP) 711, covering the Natuna Sea and the Karimata Strait, surrounded by Indonesian, Malaysian, Vietnamese and Singaporean waters and territories. The Natuna Sea in the northern part of WPP 711 lies in between Malaysian territories to the east and west, while the Karimata Strait in the southern part of WPP 711 has the Indonesian island of Sumatra to the west and Kalimantan to the east (Figure 1.1). -

4. Old Track, Old Path

4 Old track, old path ‘His sacred house and the place where he lived,’ wrote Armando Pinto Correa, an administrator of Portuguese Timor, when he visited Suai and met its ruler, ‘had the name Behali to indicate the origin of his family who were the royal house of Uai Hali [Wehali] in Dutch Timor’ (Correa 1934: 45). Through writing and display, the ruler of Suai remembered, declared and celebrated Wehali1 as his origin. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Portuguese increased taxes on the Timorese, which triggered violent conflict with local rulers, including those of Suai. The conflict forced many people from Suai to seek asylum across the border in West Timor. At the end of 1911, it was recorded that more than 2,000 East Timorese, including women and children, were granted asylum by the Dutch authorities and directed to settle around the southern coastal plain of West Timor, in the land of Wehali (La Lau 1912; Ormelling 1957: 184; Francillon 1967: 53). On their arrival in Wehali, displaced people from the village of Suai (and Camenaça) took the action of their ruler further by naming their new settlement in West Timor Suai to remember their place of origin. Suai was once a quiet hamlet in the village of Kletek on the southern coast of West Timor. In 1999, hamlet residents hosted their brothers and sisters from the village of Suai Loro in East Timor, and many have stayed. With a growing population, the hamlet has now become a village with its own chief asserting Suai Loro origin; his descendants were displaced in 1911. -

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 293 Power and Place in Southeast Asia Edited by Gerry van Klinken (KITLV) Edward Aspinall (Australian National University) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki The Making of Middle Indonesia Middle Classes in Kupang Town, 1930s–1980s By Gerry van Klinken LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC 3.0) License, which permits any non‐commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: PKI provincial Deputy Secretary Samuel Piry in Waingapu, about 1964 (photo courtesy Mr. Ratu Piry, Waingapu). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klinken, Geert Arend van. The Making of middle Indonesia : middle classes in Kupang town, 1930s-1980s / by Gerry van Klinken. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, ISSN 1572-1892; volume 293) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26508-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26542-4 (e-book) 1. Middle class--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 2. City and town life--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 3. -

Exploring Timor-Leste: - Minerals Potential

Exploring Timor-Leste: - Minerals Potential Francisco da Costa Monteiro1, Vicenti da Costa Pinto2 Pacific Economic Cooperation Council-PECC Minerals Network Brisbane, Queensland 17-18 November 2003 1 Natural Resources Counterpart, Office of President, Palacio das Cinzas, Rua Caicoli Dili, Timor-Leste, +670 7249085, [email protected] 2 Director of Energy and Minerals, Ministry of Development and Environment, Fomento Building, Timor-Leste, + 670 7236320, [email protected] Abstract The natural and mineral resources, with which Timor-Leste is endowed are waiting to be developed in an environmentally friendly manner for the greater economic and social good of the people of the this newly independent nation. The major metallic minerals in Timor-Leste are gold, copper, silver, manganese, although further investigations are needed to determine the size, their vertical and lateral distribution. Gold is found as alluvial deposit probably derived from quartz veins in the crystalline schist of (Aileu Formation). It can also be found as ephithermal mineralisation such as in Atauro island. Nearby islands, Wetar, Flores, and Sumba islands of Indonesia Republic have produced gold deposit in a highly economic quantity. In Timor-Leste, the known occurrences of these precious minerals are mostly concentrate along the northern coastal area and middle part of the country associated with the thrust sheets. The copper- gold-silver occurrences associated with ophiolite suites resembling Cyprus type volcanogenic deposits have been reported from Ossu (Viqueque district), Ossuala (Baucau district), Manatuto and Lautem districts. The Cyprus type volcanogenic massive sulphides are usually between 500.000 to a few million tons in size or larger (UN ESCAP-report, 2003). -

Data Alumni Diklat Pim Tk.Iii Badan Pengembangan Sumberdaya

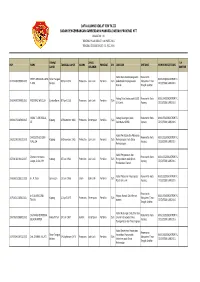

DATA ALUMNI DIKLAT PIM TK.III BADAN PENGEMBANGAN SUMBERDAYA MANUSIA DAERAH PROVINSI NTT ANGKATAN : 09 TANGGAL MULAI DIKLAT : 14 MARE 2016 TANGGAL SELESAI DIKLAT: 01 JULI 2016 TEMPAT JENIS TLP NIP NAMA TANGGAL LAHIR AGAMA PANGKAT GOL JABATAN INSTANSI NOMOR REGISTRASI LAHIR KELAMIN KANTOR Kabid Data dan Kepangkatan Pemerintah AFRET APRIANUS LOPO, Timor Tengah 00001548/DIKLATPIM TK. 197204091999031009 09 April 1972 Protestan Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a pada Badan Kepegawaian Kabupaten Timor S.SOS Selatan III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Daerah Tengah Selatan Kabag Tata Usaha pada RSUD Pemerintah Kota 00001549/DIKLATPIM TK. 196504071999031002 ANDERIAS WOLI,SH Sumba Barat 07 April 2016 Protestan Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a S.K.Lerik Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 ANIKA T.LENI BELLA, Kabag Keuangan pada Pemerintah Kota 00001550/DIKLATPIM TK. 196811251995032005 Kupang 25 November 1968 Protestan Perempuan Pembina IV/a SE Sekretariat DPRD Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Kabid Penataan dan Pelayanan DAVIDZON EDISON Pemerintah Kota 00001551/DIKLATPIM TK. 196312081985121005 Kupang 08 Desember 1962 Protestan Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a Perhubungan Pada Dinas PUAS,SH Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Perhubungan Kabid Pengawasan dan Djarmes Herminus Pemerintah Kota 00001552/DIKLATPIM TK. 197001022001121007 Kupang 05 Juni 1968 Protestan Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a Pengendalian pada Dinas Lango, S.Sos,.MM Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Pendapatan Daerah Kabid Pelayanan Medis pada Pemerintah Kota 00001553/DIKLATPIM TK. 196806152002121005 dr. M.Ihsan Lamongan 15 Juni 1968 Islam Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a RSUD SK Lerik Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Pemerintah dr.R.A.KAROLINA Kepala Rumah Sakit Umum 00001554/DIKLATPIM TK. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/25/2021 08:57:46PM Via Free Access | Lords of the Land, Lords of the Sea

3 Traditional forms of power tantalizing shreds of evidence It has so far been shown how external forces influenced the course of events on Timor until circa 1640, and how Timor can be situated in a regional and even global context. Before proceeding with an analysis of how Europeans established direct power in the 1640s and 1650s, it will be necessary to take a closer look at the type of society that was found on the island. What were the ‘traditional’ political hierarchies like? How was power executed before the onset of a direct European influence? In spite of all the travel accounts and colonial and mission- ary reports, the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century source material for this region is not rich in ethnographic detail. The aim of the writers was to discuss matters related to the execution of colonial policy and trade, not to provide information about local culture. Occasionally, there are fragments about how the indigenous society functioned, but in order to progress we have to compare these shreds of evidence with later source material. Academically grounded ethnographies only developed in the nineteenth century, but we do possess a certain body of writing from the last 200 years carried out by Western and, later, indigenous observers. Nevertheless, such a comparison must be applied with cau- tion. Society during the last two centuries was not identical to that of the early colonial period, and may have been substantially different in a number of respects. Although Timorese society was low-technology and apparently slow-changing until recently, the changing power rela- tions, the dissemination of firearms, the introduction of new crops, and so on, all had an impact – whether direct or indirect – on the struc- ture of society.