By Omar Robert Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN the LAST DAYS of the CITY Tue 11 Oct 15:30 BFI, NFT2

Internationale Filmfestspiele MORE THAN 50 Berlin BEST 66 INTERNATIONAL DIRECTOR Forum FILM FESTIVALS CALIGARI FILM PRIZE BAFICI 2016 GRAND PRIX NEW HORIZON INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL BFI LONDON FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING DATES Sun 9 Oct 20:45 Picturehouse Centeral IN THE LAST DAYS OF THE CITY Tue 11 Oct 15:30 BFI, NFT2 A Film by Tamer El Said “A melancholic love-hate poem to Cairo and the role of filmmakers in any city in pain” Jay Weissberg, Variety SYNOPSIS Downtown Cairo, 2009. Khalid, a 35 year old filmmaker is struggling to make a film that captures the soul of his city while facing loss in his own life. With the help of his friends, who send him footage from their lives in Beirut, Baghdad and Berlin, he finds the strength to keep going through the difficulty and beauty of living In the Last Days of the City. “A moving and extremely personal city symphony that takes its audience on a journey connecting the most intimate to the state of the world we are living today, a film from the heart” Jury of New Horizon International Film festival, Poland 2016. “Beautifully lensed and complexly edited in a dense patchwork of people, feelings and events” Deborah Young, The Hollywood Reporter THE FILM’S JOURNEY In the Last Days of the City was born as an idea in gradually finding a community of investors and 2006, while war was raging in Iraq and Lebanon. funders willing to take a risk on the film’s team. By the time shooting began at the very end of Throughout, Tamer’s mother was ill. -

Sneak Preview

SNEAK PREVIEW For additional information on adopting this title for your class, please contact us at 800.200.3908 x501 or [email protected] HUMAN EXPRESSIONS OF SPIRITUALITY … Edited by Margaret M. McKinnon Our Lady of Holy Cross College Bassim Hamadeh, CEO and Publisher Christopher Foster, General Vice President Michael Simpson, Vice President of Acquisitions Jessica Knott, Managing Editor/Project Editor Kevin Fahey, Marketing Manager Jess Busch, Senior Graphic Designer Melissa Barcomb, Acquisitions Editor Stephanie Sandler, Licensing Associate Copyright © 2013 by Cognella, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfi lming, and recording, or in any informa- tion retrieval system without the written permission of Cognella, Inc. First published in the United States of America in 2010 by Cognella, Inc. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-60927-950-9 (pbk) Contents Introduction 1 By Margaret McKinnon Part I Western Religions—Abrahamic Faiths Chapter 1: Judaism 25 Israel's Sacred History 27 By Eliezer Segal Chapter 2: Jewish Spirituality 43 What Is Jewish Spirituality? 45 By Martin A. Cohen Chapter 3: Christianity 49 Th e Taking of the Gospel to the Gentiles; Paul 51 -

The Square Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com The Square Discussion Guide Director: Jehane Noujaim Year: 2013 Time: 95 min You might know this director from: Rafe: Solar Mama (2012) Control Room (2004) Startup.com (2001) FILM SUMMARY THE SQUARE brings the viewer into Tahrir Square to witness the raucous energy and exultation of the Egyptian revolution as well its terror and heartrending grief, through the personal stories of six very different revolutionaries. Each comes from a different background and upholds a different philosophy and aim, but all six are fighting for a new Egypt. The film was shot over three years and culls together footage from over 1,600 hours shot by the filmmaker, her crew, and those in the streets. THE SQUARE’s verite immediacy and intimacy allows the viewer to experience the tumultuous events of the revolution, from its awe-inspiring beginnings as people first gathered in the square and the joyous celebration when Mubarak stepped down, to the violence of military crackdowns against civilian protesters, which included arrests, attacks, and killings. But this brutality cannot quell or silence the revolutionaries. They return to the square to protest against a new regime that uses the same old tools of a police state and emergency law. They return to the square again to protest against President Morsi who is then ousted from office. And they will return to the square again and again to voice their demands, unite with others, and create a culture of conscience. Both harrowing and inspiring, THE SQUARE is an important, urgent film with world-wide resonance. Its spirit of protest has inspired those in Kiev, Ukraine and Caracas, Venezuela. -

Johnny Winter Page 13

PRESORTED STANDARD PERMIT #3036 WHITE PLAINS NY Vol. V No. XXXV Thursday, September 15, 2011 Westchester’s Most Influential Weekly A Living Memorial at Ground Zero Page 4 Is America Khalid Abdalla: A Scotsman in Hollywood Page 8 Awake? Johnny Winter Page 13 Follies Forever Page 14 Tarrytown Board Cover-up Page 18 Schneiderman Balks at Banks Page 19 By HENRY J. STERN, Page 25 What Your Doctor Won’t (or Can’t) Tell You Page 26. westchesterguardian.com Page 2 The Westchester GuardiaN THURSDAY, SePTeMBER 15, 2011 Of Significance communitySection Community Section ...................................................................2 Books ........................................................................................2 BOOKS calendar ...................................................................................4 commemoration .....................................................................4 The Retired (Try To) Strike Back—Chapter 19 – Revealed crime .......................................................................................7 cultural perspective .................................................................8 By ALLAN LUKS education .................................................................................9 Working part-time for more these three years, your personal concerns. actors humor ...................................................................................11 than three years, the four couples coming out as their real selves is a dramatic way to are ready to complete their educa- end a movie.” -

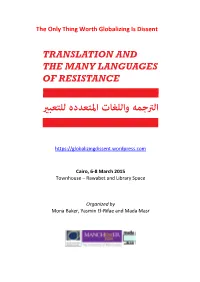

The Only Thing Worth Globalizing Is Dissent

The Only Thing Worth Globalizing Is Dissent https://globalizingdissent.wordpress.com Cairo, 6‐8 March 2015 Townhouse – Rawabet and Library Space Organized by Mona Baker, Yasmin El‐Rifae and Mada Masr Acknowledgements The conference organizers wish to thank the following for their support and input: The Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK, for funding the Research Project that concludes with this conference (https://globalizingdissent.wordpress.com/research‐project/) The School of Arts, Languages and Cultures, and the Centre for Translation & Intercultural Studies, University of Manchester, for financial and logistic support Al-Mamoun for Translation, Gaza, Palestine, for producing the Arabic translation of the abstracts (http://almamoun.ps/public/). Khalid El‐Shehari, Durham University, Sameh Fekry Hanna, University of Leeds, and Walid El‐Hamamsy, Cairo University, for assistance and advice on translating material for the conference Rebecca Johnson for assistance with publicity Dina Kafafi for managing all logistical support and for her invaluable advice during the months and weeks leading up to the conference Townhouse Rawabet and William Wells for hosting the event Facilities at Townhouse and Information on Venue Free access to Internet is available throughout the venue. No password is needed. Interpreting is provided for all plenaries and parallel sessions held in the Rawabet Space, but not in the Library Space Lunch and refreshments will be available in the Rawabet Space Phone number for the venue: 02‐25768086 Rawabet -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

Video Terrorism

VIDEO TERRORISM 9/11 (2002) This heartfelt documentary was created by award-winning French filmmakers Jules and Gedeon Naudet, who simply set out to make a movie about a rookie NYC fireman and ended up filming the tragic event that changed our lives forever. The program includes additional footage and interviews with the heroic firefighters, rescue workers and the Naudet brothers, providing exclusive insight to their extraordinary firsthand experience of the day's events. 9/11: Press for Truth (2006) Based partly on Paul Thompson's book The Terror Timeline, this documentary chronicles the efforts of family members who lost loved ones in the 9/11 attack as they hound powerful officials to uncover the truth. The families succeed in generating an independent investigation, but more questions than answers emerge as the film spotlights secretive politicians, buried news items, government press conferences lacking substance and more. 444 Days to Freedom: What Really Happened in Iran (1997) Relive the dramatic events surrounding the infamous 444-day Iranian hostage crisis when, in 1979, a gang of radical Islamic students demanding the return of the Shah took prisoner Tehran's U.S. embassy staff. Despite the captors' eventual retreat, Jimmy Carter's presidency was brought to ruin and America's spirit was broken. Using rare archival footage, interviews and revealing documents, this film chronicles the hostages' harrowing ordeal. 60 Minutes - In Search of Bin Laden (September 25, 2005) Four years after 9/11, why hasn't Osama bin Laden been caught? Steve Kroft interviews Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf, who says bin Laden is still revered by many in his country. -

From Novel to Movie: Politics of De

FROM NOVEL TO MOVIE: POLITICS OF DE- ISLAMIZATION AS SEEN IN THE KITE RUNNER A GRADUATING PAPER Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Gaining the Bachelor Degree in English Literature By: Haryo Yudanto 15150045 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND CULTURAL SCIENCES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF SUNAN KALIJAGA YOGYAKARTA 2019 A FINAL PROJECT STATEMENT i NOTA DINAS ii APPROVAL iii MOTTO My mom my everything You’llneverknowuntilyou’vetried. Everything will be fine in the end. If itisnotfine,it’snottheend. I will never give up in what I want. I do believe in ways somehow, Allah will always give more than good. Call me pendekar iv DEDICATION I dedicate this graduating paper to; My beloved family, especially my beloved mom and Everyone who has struggled to help me complete this research v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Assalamu’alaikumwr.wb First of all, my greatest thankful appreciation is to Allah SWT who has been giving me His blessing so that I am able to finish my graduating paper. I would like to express my deeply appreciations for people who have supported me. They are; 1. Drs. Akhmad Patah, M.Ag, as the Dean of Faculty of Adab and Cultural Sciences, UIN Sunan Kalijaga. 2. Dr. Ubaidillah, S.S., M.Hum. as the Head of English Department. 3. Dr. Witriani, S.S., M.Hum. as my academic advisor. 4. Danial Hidayattullah, S.S., M.Hum. as beloved advisor of my graduating paper. 5. Dr. Ubaidillah, S.S., Ulyati Retno Sari, S.S., M.Hum., Febriyanti Dwiratna Lestari, S.S,MA., Fuad Arif Fudiyartanto, S.Pd., M.Hum., M.Ed., Dwi Margo Yuwono, S.Pd., M.Hum., Arif Budiman, S.S., M.A., Bambang Hariyanto, S.S., M.A., Aninda Aji Siwi, S.Pd., M.Pd., Harsiwi Fajar Sari, S.S., M.A., Nisa Syuhda, and Rosiana Rizqy Wijayanti, S.Hum., M.A. -

October 2016

OCTOBER 2016 I, DANIEL BLAKE | DE PALMA SCOTLAND LOVES ANIME AFRICA IN MOTION | LUMINATE SMHAFF | BLACK STAR GLASGOW FILM THEATRE BOX OFFICE 0141 332 6535 • WWW.GLASGOWFILM.ORG CONTENTS DIARY 4–6 The Secret Life of Pets 32 35mm: Quay Brothers Meet The Shining 15 12 Christopher Nolan Tharlo 10 The 48 Hour Film Project 11 Train to Busan 14 Access Film Club: Little Men 17 Under the Shadow 7 Akeelah and the Bee 32 Visible Cinema: The Grump 17 American Honey 11 AFRICA IN MOTION The Ana Trilogy I & II 13 The Battle of Algiers 23 Atomic - Living in Dread and Promise 13 In the Last Days of the City 23 The Beatles: Eight Days a Week 18 BLACK STAR Baden Baden 13 The Fabulous Nicholas Brothers 24 The Battle of the Somme Stormy Weather 24 27 with Live Score EDINBURGH SPANISH Belladonna of Sadness 29 FILM FESTIVAL Black 27 Lovers: A True Story 26 Blazing Saddles 29 Mr Kaplan 26 Blinky Bill the Movie 31 Sex, Maracas & Chihuahuas 26 Blow Out 9 EVENT CINEMA Bobby Sands: 66 Days 14 Bolshoi Ballet: The Bright Stream 36 Burn Burn Burn 14 Bolshoi Ballet: A Contemporary Evening 36 Courted 11 Bolshoi Ballet: The Golden Age 35 De Palma 9 Bolshoi Ballet: A Hero of Our Time 36 The Exorcist (Director’s Cut) 30 Bolshoi Ballet: The Nutcracker 36 The Fencer 7 Bolshoi Ballet: The Sleeping Beauty 36 The First Monday in May 10 Bolshoi Ballet: Swan Lake 36 From Dusk Till Dawn 30 Branagh Theatre Live: The Entertainer 33 The Girl With All the Gifts 7 NT Live: Hedda Gabler 35 Halloween 29 NT Live: No Man’s Land 34 I, Daniel Blake 12 NT Live: Saint Joan (Encore screening) -

The Arab Archive 21

20 THEORY ON DEMAND 02. TIME CAPSULES OF CATASTROPHIC TIMES MARK R. WESTMORELAND1 I wish we could just forget things, and I wish we could simply not have archives. It’s liberating in a way, living with YouTube, as ephemeral records, is liberating.2 — Akram Zaatari Until we find ourselves in a utopian moment, the archive is going to continually be in play, much like it is today, with varying degrees of urgency or with various targets. To continue to build and assemble out of these moments of recent history is something that, regardless of whether the revolution is completely successful or a complete failure, remains a political and humanistic imperative, something we must do to continue to build and go forward.3 — Sherief Gaber Vis-à-vis Two figures stand facing the calamities of history. One figure’s face is full of wonder and horror, unable to look away from the spectacle of death while backpedaling away from the waste piling up in the wake of progress and power. The other’s turns away from our gaze to direct us at his own vision of recurrent catastrophe. The first makes copious notes that desperately document the ruins before they disappear under more rubble. The second quickly sketches the fleeting moments of critical clarity that appear in a flash and then vanish as if they never happened. In the desperation of the moment, the first cannot organize these memos, but anxiously hides them so they won’t vanish in the storm of violence as time marches on. Despite the urgency of the situation, the second knows we’ve seen it all before and are no longer moved, nevertheless remaining steadfast to bear witness and remember the symbolic connections being severed. -

Cooley-Mastersreport-2015

Copyright by Claire Sloan Cooley 2015 The Report Committee for Claire Sloan Cooley Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: The Citizen Viewer: Questioning the Democratic Authority of the Camera Phone Image APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Blake Atwood Karin Wilkins The Citizen Viewer: Questioning the Democratic Authority of the Camera Phone Image by Claire Sloan Cooley, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Dedication To my shilla, and the wonderful community of friends and family I made in Egypt. Acknowledgements I am grateful to my amazing advisor Blake Atwood for his help, thoughts, and guidance. I also could not have done any of this without my family Charlie, Grosvie, Frances, and Henry, and their unconditional love and support. v Abstract The Citizen Viewer: Questioning the Democratic Authority of the Camera Phone Image Claire Sloan Cooley, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Blake Atwood The inundation of mobile phone images has dramatically changed how information about current events is disseminated, accessed, and understood. The mobile camera phone was significant to the Egyptian Revolution and the Green Movement in Iran, and scholars who have considered citizen journalist images in these contexts suggest that they have the power to create democratic “deterritorialized” communities and provide objective evidence. This scholarship has assumed a dangerous link between citizen journalist images and democracy, and it has overlooked opportunities for thoughtful comparison of the use of citizen journalist footage in Iran and Egypt. -

The Monarch Edition 19.4 March 2010 (Pdf)

INSIDE: Opposing Viewpoints: Youth Revolt? (see page 2) ServingServingServing the thethe Archbishop ArchbishopArchbishop Mitty MittyMitty Community CommunityCommunity Volume 19 Number 4 March 2010 Behind the Scenes: Mitty Parking East Lot Q&A with Mrs. Cathy Campbell So what are your main concerns/hopes for Mitty parking and Mitty drivers? Well, I hope students realize that we’re here to help them and not to persecute them. We want to get them into class on time and safely, but also to park legally. So we try to get as many as we can in here and, if we can’t, we try to accommodate them in other parking lots. What was your most frightening or exciting moment in a Mitty parking lot? Some strangers tried to drop a bag off in the bushes and then tried to get onto campus. It was clear that they were trying to be where they shouldn’t be for the wrong reasons. I thought that we were here just to park the kids and then be done, but, yeah, there’s more than that…there are out- side influences trying to get to you guys. What would you like to say about your reputation as a parking lot lady? The official term is “parking lot supervisor.” Other terms are “parking lot mom,” “parking lot Nazi,” and “parking lot lady.” You know, I just love the kids and it’s fun. Most of them don’t realize I went here and it was open campus, so I know all the ways to get in and out.