Oxford University's Bodleian Library Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINUTES of the 84Th MEETING of AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD at the VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO on WEDNESDAY 27Th JANUARY 2016

MINUTES OF THE 84th MEETING OF AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD AT THE VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO ON WEDNESDAY 27th JANUARY 2016 Present: - Rupert Clark – Chairman & Treasurer Peter Cole - Secretary. 1. Chairman’s Report Copies of Nicholas Cooper’s Aynho book have become available for sale at £15. A visit to Rousham House suggested last year would have to be on a Sunday afternoon. Let Rupert know if you would like this to be arranged. 2. Secretary’s Report Rupert, Keith and Peter as representatives of the Cartwright Archive have met Sarah Bridges (Archivist) at the Northants Records Office to discuss the Archive’s conservation and future. Further updates once the Charity Committee has met in February. 3. “A History of the University of Oxford” by Alastair Lack Oxford is the third oldest university in Europe, behind Bologna in Italy and the Sorbonne in Paris. There were students in Oxford in the 1090s, but this was not under grad education, as we know it, more like private tutoring. Various people established “halls” (like a boarding house) around the Church of St Mary the Virgin. Students were between 12 and 15 years old, they drank, they gambled and as the untrained hall owners did the teaching they didn’t learn much. Little changed much until 1170 when King Henry II demanded that all English students at the Sorbonne should return to England as he was concerned about a brain drain. Oxford was the only established place of study for them to return to. In 1196, the first account of these academic halls was written by Geoffrey of Monmouth; he was a prominent intellect of the day and had visited Oxford to presented three lectures on law. -

The Clarendon Building Conservation Plan

The Clarendon Building The Clarendon Building, OxfordBuilding No. 1 144 ConservationConservation Plan, April Plan 2013 April 2013 Estates Services University of Oxford April 2013 The Clarendon Building, Oxford 2 Conservation Plan, April 2013 THE CLARENDON BUILDING, OXFORD CONSERVATION PLAN CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Purpose of the Conservation Plan 7 1.2 Scope of the Conservation Plan 8 1.3 Existing Information 9 1.4 Methodology 9 1.5 Constraints 9 2 UNDERSTANDING THE SITE 13 2.1 History of the Site and University 13 2.1.1 History of the Bodleian Library complex 14 2.2 History of the Clarendon Building 16 3 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CLARENDON BUILDING 33 3.1 Significance as part of the City Centre, Broad Street, Catte Street, and the 33 Central (City and University) Conservation Area 3.2 Significance as a constituent element of the Bodleian Library complex 35 3.3 Architectural Significance 36 3.3.1 Exterior Elevations 36 3.3.2 Internal Spaces 39 3.3.2.1 The Delegates’ Room 39 3.3.2.2 Reception 40 3.3.2.3 Admissions Office 41 The Clarendon Building, Oxford 3 Conservation Plan, April 2013 3.3.2.4 The Vice-Chancellor’s Office 41 3.3.2.5 Personnel Offices 43 3.3.2.6 Staircases 44 3.3.2.7 First-Floor Spaces 45 3.3.2.8 Second-Floor Spaces 47 3.3.2.9 Basement Spaces 48 3.4 Archaeological Significance 48 3.5 Historical and Cultural Significance 49 3.6 Significance of a functioning library administration building 49 4 VULNERABILITIES 53 4.1 Accessibility 53 4.2 Maintenance 54 4.2.1 Exterior Elevations and Setting 54 4.2.2 Interior Spaces 55 5 CONSERVATION -

Literature in Context: a Chronology, C16601825

Literature in Context: A Chronology, c16601825 Entries referring directly to Thomas Gray appear in bold typeface. 1660 Restoration of Charles II. Patents granted to reopen London theatres. Actresses admitted onto the English and German stage. Samuel Pepys begins his diary (1660 1669). Birth of Sir Hans Sloane (16601753), virtuoso and collector. Vauxhall Gardens opened. Death of Velàzquez (15591660), artist. 1661 Birth of Daniel Defoe (c16611731), writer. Birth of Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea (16611720), writer. Birth of Sir Samuel Garth (16611719). Louis XIV crowned in France (reigns 16611715). 1662 Publication of Butler’s “Hudibras” begins. The Royal Society is chartered. Death of Blaise Pascal (16231662), mathematician and philosopher. Charles II marries Catherine of Braganza and receives Tangier and Bombay as part of the dowry. Peter Lely appointed Court Painter. Louis XIV commences building at Versailles with Charles Le Brun as chief adviser. 1663 Milton finishes “Paradise Lost”. Publication of the Third Folio edition of Shakespeare. The Theatre Royal, Bridges Street, opened on the Drury Lane site with a revival of Fletcher’s “The Humorous Lieutenant”. Birth of Cotton Mather (16631728), American preacher and writer. 1664 Birth of Sir John Vanbrugh (16641726), dramatist and architect. Birth of Matthew Prior (16641721), poet. Lully composes for Molière’s ballets. “Le Tartuffe” receives its first performance. English forces take New Amsterdam and rename it New York. Newton works on Theory of Gravity (16641666). 1665 The Great Plague breaks out in London. Newton invents differential calculus. The “Journal des Savants”, the first literary periodical, is published in Paris. -

Oxford Map V3

NR No 29, known as Green House, was built SG EP for the idealist philosopher and liberal TH NORTH Green. A fellow of Balliol, he died a year ST GILES AND TO THE EAST EAST OF PARKS ROAD SPSJ St Philip and St James. The grand later, aged 45. NP&EL Nuclear Physics and Engineering BD Go through the gate opposite Keble, parish church for the new residential JT Radiohead were first signed to a Labs. Arup’s fan-shaped nuclear and turn right at TG Jackson’s joyously developments in north Oxford. Built by record label after a gig at the Jericho accelerator can be enjoyed for its purely inappropriate Electrical Laboratory (EL), GE Street (1860-6) in doctrinal Gothic Tavern in 1991; other bands local to the sculptural qualities, while the surfaces, with its garlanded centrepiece Revival, but it’s hard not to be impressed town include Ride and Supergrass. compared to Martin’s contemporary (1908-10). Following the route through by the scale and complete authority of RO The Radcliffe Observatory is arguably Brutalist work, are positively ornamental stodgy neo-Georgian, Hawkins Brown’s its execution. the most beautiful such building ever (1971-6) SG:BA Impressive late 17th-century design Biochemistry Department appears as an NME Suburban Gothic. An important constructed. A defining work of English MI Tastefully done modernist Maths explosion of colour. (Limited access) early example of the centrally planned Neoclassicism, it was built by Institute from 1964-6, following the one on the corner, set back a little for UM University Museum (1855-60). -

Radcliffe Observatory Quarter Walton Street Wall Strategy Document 2 Contents

Radcliffe Observatory Quarter Walton Street Wall Strategy Document 2 Contents Section Description Page 1 Introduction 5 2 History of the Wall 2.1 General history 6 2.2 Historic maps of the wall 7 2.3 Description of the wall 12 2.4 Significance of the wall 14 3 Walton Street 3.1 General description of Walton Street 18 3.2 Walton Street frontage conditions 20 3.3 Walton Street views and sections 28 4 Public and Private Realm 4.1 Spatial typologies in Oxford 30 4.2 Central University Area 34 4.3 Keble College and South Parks Road 36 4.4 Walton Street and the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter 38 4.5 Colleges, hospitals and hotels 40 4.6 Spatial typologies and the development of the Radcliffe 42 Observatory Quarter 5 Approaches to Development 5.0 Introduction 44 5.1 Retain the wall as it is today 45 5.2 Retain the wall with modifications 46 5.3 Retain the wall with engaged buildings 47 5.4 Retain the wall built into new buildings 48 5.5 Lower the wall 49 5.6 Remove the wall completely 50 5.7 Remove the wall but retain key sections 51 6 Conclusion 52 3 4 1 Introduction This report examines the wall to the west of the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter (ROQ), Green Woodstock Road which forms its boundary with Walton Street. It was originally built as a demesne Templeton wall enclosing and protecting the properties of the Radcliffe Observatory and the College Radcliffe Infirmary. Although this Report considers the history and significance of the wall, it primarily examines the spatial character of the area around the wall and looks at how it has changed over time. -

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2 On foot from Broad Street by Malcolm Graham (illustrated by Edith Gollnast, cartography by Alun Jones) Chapter 1 – Broad Street to Ship Street The walk begins at the western end of Broad Street, outside the Fisher Buildings of Balliol College (1767, Henry Keene; refaced 1870).1 ‘The Broad’ enjoyably combines grand College and University buildings with humbler shops and houses, reflecting the mix of Town and Gown elements that has produced some of the loveliest townscapes in central Oxford. While you savour the views, it is worth considering how Broad Street came into being. Archaeological evidence suggests that the street was part of the suburban expansion of Oxford in the 12th century. Outside the town wall, there was less pressure on space and the street is first recorded as Horsemonger Street in c.1230 because its width had encouraged the sale of horses. Development began on the north side of the street and the curving south side echoes the shape of the ditch outside the town wall, which, like the land inside it, was not built upon until c. 1600. Broad Street was named Canditch after this ditch by the 14th century but the present name was established by 1751.2 Broad Street features in national history as the place where the Protestant Oxford Martyrs were burned: Bishops Latimer and Ridley in 1555 and Archbishop Cranmer in 1556.3 A paved cross in the centre of Broad Street and a plaque on Balliol College commemorate these tragic events. In 1839, the committee formed to set up a memorial considered building a church near the spot but, after failing to find an eligible site, it opted instead for the Martyrs’ Memorial (1841, Sir George Gilbert Scott) in St Giles’ and a Martyrs’ aisle to St. -

Oxford (UK), the Entrance to Broad Street, at Catte Street (East) End

Oxford (UK), the entrance to Broad Street, at Catte Street (east) end, looking towards Radcliffe Square (©Ozeye 2009) Oxford (UK), view of the East end of Broad Street, with the Weston Library on the left, Oxford Martin School (Indian Institute) straight ahead, and the Bodleian Libraries' Clarendon Building on the right (© Bodleian Libraries Communications team (John Cairns) 2015) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, showing the Clarendon Building, Sheldonian Theatre and the History of Science Museum (©Komarov 2016) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, looking towards the Clarendon Building and Sheldonian Theatre (©Linsdell 1989) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, looking towards the Clarendon Building (©Elbers 2018) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, looking towards the Sheldonian Theatre, Clarendon Building in the background (©Addison 2010) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, Sheldonian Theatre (©Ozeye 2009) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, the History of Science Museum (©Hawgood 2009) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, the History of Science Museum (©Wiki alf 2006) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, Blackwells as viewed from the History of Science Museum opposite on Broad Street (©Ozeye 2009) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, looking towards the Sheldonian Theatre and the History of Science Museum (©Trimming 2009) Oxford (UK), Broad Street, floor plan of the area around the Clarendon building, Sheldonian Theatre, the History of Science Museum and the opposite the Bodleian Weston Library where the ‘History and Mystery’ of the Sheldonian Heads exhibition will take place in 2019 (©HistoricEngland 2018) Plan of Sheldonian and some of the Bodleian complex showing quadrangles created by the placement of the Sheldonian(©University of Oxford 2012, New Bodleian Library: Design and Access Statement, Wilkinson Eyre Associates (March, 2010)) Heads at the Hartcourt Arboretum, Oxford University‘s botanic garden (potentially 2nd generation from the History of Science Museum. -

OXFORD Devised by Clemence Schultze, D.Phil., and Thomas Sopko

A BARBARA PYM WALK THROUGH OXFORD Devised by Clemence Schultze, D.Phil., and Thomas Sopko And that sweet city with her dreaming spires She needs not June for beauty’s heightening, Lovely all times she lies, lovely to-night! – Matthew Arnold Through a rift in the trees he caught his first real glimpse of Oxford – in that ineffectual moonlight an underwater city, its towers and spires standing ghostly, like the memo- rials of lost Atlantis, fathoms deep. – Edmund Crispin [1] Numbers in square brackets correspond to the numbers on the map. THE STARTING POINT IS THE ENTRANCE OF ST HILDA’S COLLEGE ON COWLEY PLACE [1] St Hilda’s is the college of novelists D. K. Broster and Catherine Heath, poets Jenny Joseph and Wendy Cope, and detective fiction writer Val McDermid. It was founded in 1893 by Dorothea Beale – educational reformer, suffragist, and Principal of the Cheltenham Ladies’ College – and it remained an all-women’s col- lege until 2008, making it the last single-sex college in the University of Oxford. When Barbara was a student here in the 1930s the college buildings comprised Hall and South Buildings (the former described below) and a ‘temporary’ wooden Chapel (1925-1969) located where Garden Building now stands. South Building was originally a family house named Cowley Grange, built in the 1870s by Christ Church chemistry tutor Augustus Vernon Harcourt. From 1902-1920 it was a women's teacher training college called Cherwell Hall; St Hilda’s obtained the leasehold in 1920 and purchased the building outright in 1949. During the 1950s the former Milham Ford School building, located between Hall and South, was purchased, the kitchens and dining hall were expanded, and the Prin- cipal’s House and a Porters’ Lodge constructed. -

Oxford Is... Widening Access PAGES 4 and 5

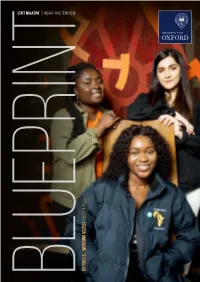

STAFF MAGAZINE | Michaelmas term 2018 PAGES 4 and 5 PAGES Oxford is... widening access widening access is... Oxford contributors inSIDE EDITORIAL TEAM 3 The Lily Garden Annette Cunningham 4 COVER: Oxford is... Internal Communications Manager Widening Access Public Affairs Directorate 6 Making Healthcare Smarter with AI Shaunna Latchman 8 Vice-Chancellor’s Innovation Awards Communications Officer 2018 Public Affairs Directorate 10 Teamwork: Wytham Woods Caretakers Read me online at Laetitia Velia www.ox.ac.uk/ 12 Public Engagement Senior Graphic Designer blueprint with Research Public Affairs Directorate 14 Intermission OTHER CONTRIBUTORS 16 Pushing the Boundaries 18 Day in the Life: Dale White 20 Oxford Against Sexual Violence Mark Curthoys Chris McIntyre Abby Swift Research Editor, Oxford Media Relations Manager, Communications Officer, 21 Active at Oxford Dictionary of National Impact & Innovation Academic Administration Biography (Research and Communications, Public Division 22 CuriOXities publishing project of the Affairs Directorate History Faculty and OUP) 23 Exhibitions 25 Research Round-up 26 Advancing Education: Canvas@Oxford 26 Mindful Employer Charter Megan Thomas Vanessa Worthington Communications Executive, Widening Access and Participation 27 News Oxford University Press Coordinator (BAME), Undergraduate Admissions and Outreach 34 Bookshelf 35 Ten-Year Celebration Milestone On the cover: Mary Bonsu, studying Law with French Law at St Catherine’s College, is one of the 19 Target Oxbridge students who have joined the University this academic year. Fleming She is joined by Esther Agbolade (front) and Ruth Akhtar Dave (right). See the full feature on pages 4 and 5. Cover photo: Dave Fleming 2 Blueprint | Michaelmas term 2018 inSIDE The Lily Garden Botanist Dr Chris Thorogood produced an oil painting for an exhibition earlier this year at Magdalen College titled The Flora & Fauna of Magdalen College. -

Oxford Town & Gown Guide

OXFORD – TOWN AND GOWN ATTRACTIONS Compiled by Phyllis Ferguson – AUGUST 2017 Oxford Visitor Information Centre http://www.experienceoxfordshire.org/venue/information-ticket-sales- oxford-visitor-information-centre/ TOWN * Town Hall https://www.oxfordtownhall.co.uk/ * Carfax Tower http://www.free-city-guides.com/oxford/carfax-tower/ * Oxford Castle https://www.oxfordcastleunlocked.co.uk/ * St Michael at the Northgate http://www.smng.org.uk/wp/ * The Synagogue http://www.ojc-online.org/ * The Oratory http://www.oxfordoratory.org.uk/ * The Rivers http://www.oxfordrivercruises.com/ • Cherwell • Isis • Thames * The parks http://www.parks.ox.ac.uk/home • Christ Church Meadow • The University Park • Port Meadow – the Perch, Medley Manor Farm (Pick your own), Binsey Church and the sacred well, Frideswide Nunnery, the Trout * The Markets https://www.oxford.gov.uk/info/20035/events/791/markets_and_fairs • The covered Market, Gloucester Green • Open Markets: 7.30-15h - Wed. 16th and the Farmer’s market on Thurs. 17h August * The Museums https://www.ox.ac.uk/visitors/visiting-oxford/visiting- museums-libraries-places?wssl=1 • Modern Art Oxford – 10-17 https://www.modernartoxford.org.uk • The Story Museum – 10-17h http://www.storymuseum.org.uk/ • The City of Oxford Museum – 10-17h http://www.museumofoxford.org.uk/ GOWN * The Sheldonian https://www.admin.ox.ac.uk/sheldonian/ * Old University Quarter * Divinity School https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divinity_School,_Oxford * The Clarendon Building http://www.oxfordhistory.org.uk/broad/buildings/south/clarendon.html -

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2 On foot from Broad Street by Malcolm Graham © Oxford Preservation Trust, 2014 This is a fully referenced text of the book, illustrated by Edith Gollnast with cartography by Alun Jones, which was first published in 2014. Also included are a further reading list and a list of common abbreviations used in the footnotes. The published book is available from Oxford Preservation Trust, 10 Turn Again Lane, Oxford, OX1 1QL – tel 01865 242918 Contents: Broad Street to Ship Street 1 – 8 Cornmarket Street 8 – 14 Carfax to the Covered Market 14 – 20 Turl Street to St Mary’s Passage 20 – 25 Radcliffe Square and Bodleian Library 25 – 29 Catte Street to Broad Street 29 - 35 Abbreviations 36 Further Reading 36-37 Chapter 1 – Broad Street to Ship Street The walk begins at the western end of Broad Street, outside the Fisher Buildings of Balliol College (1767, Henry Keene; refaced 1870).1 ‘The Broad’ enjoyably combines grand College and University buildings with humbler shops and houses, reflecting the mix of Town and Gown elements that has produced some of the loveliest townscapes in central Oxford. While you savour the views, it is worth considering how Broad Street came into being. Archaeological evidence suggests that the street was part of the suburban expansion of Oxford in the 12th century. Outside the town wall, there was less pressure on space and the street is first recorded as Horsemonger Street in c.1230 because its width had encouraged the sale of horses. Development began on the north side of the street and the curving south side echoes the shape of the ditch outside the town wall, which, like the land inside it, was not built upon until c. -

Eastern Colleges- University Buildings Oxford Historic

OXFORD HISTORIC URBAN CHARACTER ASSESSMENT HISTORIC URBAN CHARACTER AREA 33: EASTERN COLLEGES- UNIVERSITY BUILDINGS The HUCA is located within broad character Zone K: The eastern colleges. The broad character zone comprises of the eastern part of the historic city which is dominated by the enclosed quadrangles, gardens and monumental buildings of the medieval and post-medieval University and colleges. Summary characteristics • Dominant period: Post-medieval (with important medieval elements). • Designations: Nine Grade I and nine Grade II listings. Central Conservation Area. • Archaeological Interest: The area has high potential for significant archaeological remains despite extensive localised truncation resulting from the construction of the Bodleian underground book stacks. It has potential to preserve remains relating to the Late Saxon and medieval defences, also Late Saxon, medieval and post- medieval tenements and the medieval churchyard of St Mary’s, the University church. The area formed part of the medieval University “schools” area and also the printing and book binding quarter. It contains exceptional standing medieval and post-medieval built fabric. • Character: Forms a north-south ‘spine’ of University of Oxford structures comprising of library buildings, University meeting house, Science museum and the University church. • Spaces: Notable area of publicly accessible paved open space created by linkage of Broad Street, Radcliffe Square, the Schools Quadrangle, Clarendon Quadrangle and St Mary’s Churchyard. • Road morphology: Preserves elements of rectilinear Late Saxon to medieval street network, altered by the formation of 18th century Radcliffe Square. • Plot morphology: Large regular and curvilinear plots for monumental Historic urban character area showing modern University structures. urban landscape character types.