Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kemble Church Before 1876 and the Restoration: As Seen in Images by John Buckler, HE Relton, Henry Taunt and an Anonymous 19Thc Watercolourist

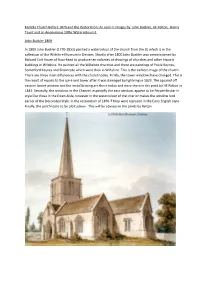

Kemble Church Before 1876 and the Restoration: As seen in images by John Buckler, HE Relton, Henry Taunt and an Anonymous 19thc Watercolourist. John Buckler 1809 In 1809 John Buckler (1770-1851) painted a watercolour of the church from the SE which is in the collection of the Wiltshire Museum in Devizes. Shortly after 1800 John Buckler was commissioned by Richard Colt Hoare of Stourhead to produce ten volumes of drawings of churches and other historic buildings in Wiltshire. He painted all the Wiltshire churches and there are paintings of Poole Keynes, Somerford Keynes and Shorncote which were then in Wiltshire. This is the earliest image of the church. There are three main differences with the church today. Firstly, the tower windows have changed. This is the result of repairs to the spire and tower after it was damaged by lightning in 1823. The squared off eastern lancet window and the metal bracing are there today and were there in the print by HE Relton in 1843. Secondly, the windows in the Chancel, especially the east window, appear to be Perpendicular in style like those in the Ewen Aisle, however in the watercolour of the interior makes the window look earlier of the Decorated Style. In the restoration of 1876-7 they were replaced in the Early English style. Finally, the porch looks to be a bit askew. This will be obvious in the prints by Relton. H. E. Relton 1843 These two prints are from ‘Sketches of Churches, with Short Descriptions’ by H. E. Relton; London (1843). He visited quite a few churches in Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Berkshire and he wrote a few notes on each of the churches. -

Studental Dental Practice

brookesunion.org.ukbrookesunion.org.uk | fb.com/BrookesUnion | fb.com/BrookesUnion | | @BrookesUnion @brookesunion Advertisement STUDENTAL DENTAL PRACTICE CONTENTs Studental is currently accepting new nhs Patients! • e re se of e r en rcice i Introduction qualified, caring and respectful team of dentists 4-5 and staff. Areas of Oxford • e re oce on e for Brookes 7–8 Headington Campus in the Colonnade building. Sites to see and things to do • We are taking on new NHS and private patients, 10-17 even if only for short term periods. • We can cater for the families of students as well as Events students themselves. 18–19 • Even if you have a dentist elsewhere (back home), Food and drink you are still able to come and see us (you do not ind s n ms 20-25 need to deregister from your other dental surgery). for Brookes Clubbing guide • Some of you might be eligible for exemption from Headington Campus, 26-27 en crges ese enuire uen Colonnade Building, Getting around reception. 3rd Floor, OX3 0BP 30-31 • We are able to provide emergency appointments. • We have an Intra-oral camera for a closer view of Where to go shopping dental problems. We can also provide wisdom 32-35 eebring our t er tooth extractions, specialist periodontal treatment, Sustainability specialist prosthodontic treatments, implants, 36-39 tooth whitening, specialist root canal treatments with our microscope, and invisalign treatments. 40-41 Staying safe State of the art dental care is now 42-46 Welfare within everyone’s reach 47-52 Directory [email protected] intments esi n r site While care has been taken to ensure that all information is correct at the time of going to print, we do www.studental.co.uk not assume responsibility for any errors. -

MINUTES of the 84Th MEETING of AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD at the VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO on WEDNESDAY 27Th JANUARY 2016

MINUTES OF THE 84th MEETING OF AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD AT THE VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO ON WEDNESDAY 27th JANUARY 2016 Present: - Rupert Clark – Chairman & Treasurer Peter Cole - Secretary. 1. Chairman’s Report Copies of Nicholas Cooper’s Aynho book have become available for sale at £15. A visit to Rousham House suggested last year would have to be on a Sunday afternoon. Let Rupert know if you would like this to be arranged. 2. Secretary’s Report Rupert, Keith and Peter as representatives of the Cartwright Archive have met Sarah Bridges (Archivist) at the Northants Records Office to discuss the Archive’s conservation and future. Further updates once the Charity Committee has met in February. 3. “A History of the University of Oxford” by Alastair Lack Oxford is the third oldest university in Europe, behind Bologna in Italy and the Sorbonne in Paris. There were students in Oxford in the 1090s, but this was not under grad education, as we know it, more like private tutoring. Various people established “halls” (like a boarding house) around the Church of St Mary the Virgin. Students were between 12 and 15 years old, they drank, they gambled and as the untrained hall owners did the teaching they didn’t learn much. Little changed much until 1170 when King Henry II demanded that all English students at the Sorbonne should return to England as he was concerned about a brain drain. Oxford was the only established place of study for them to return to. In 1196, the first account of these academic halls was written by Geoffrey of Monmouth; he was a prominent intellect of the day and had visited Oxford to presented three lectures on law. -

Oxfordshire Local History News

OXFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY NEWS The Newsletter of the Oxfordshire Local History Association Issue 128 Spring 2014 ISSN 1465-469 Chairman’s Musings gaining not only On the night of 31 March 1974, the inhabitants of the Henley but also south north-western part of the Royal County of Berkshire Buckinghamshire, went to bed as usual. When they awoke the following including High morning, which happened to be April Fools’ Day, they Wycombe, Marlow found themselves in Oxfordshire. It was no joke and, and Slough. forty years later, ‘occupied North Berkshire’ is still firmly part of Oxfordshire. The Royal Commission’s report Today, many of the people who live there have was soon followed by probably forgotten that it was ever part of Berkshire. a Labour government Those under forty years of age, or who moved in after white paper. This the changes, may never have known this. Most broadly accepted the probably don’t care either. But to local historians it is, recommendations of course, important to know about boundaries and apart from deferring a decision on provincial councils. how they have changed and developed. But in the 1970 general election, the Conservatives were elected. Prime Minister Edward Heath appointed The manner in which the 1974 county boundary Peter Walker as the minister responsible for sorting the changes came about is little known but rather matter out. He produced another but very different interesting. Reform of local government had been on white paper. It also deferred a decision on provincial the political agenda since the end of World War II. -

NORTH OXFORD VICTORIAN SUBURB CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Consultation Draft - January 2017

NORTH OXFORD VICTORIAN SUBURB CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Consultation Draft - January 2017 249 250 CONTENTS SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE 5 Reason for appraisal 7 Location 9 Topography and geology 9 Designation and boundaries 9 Archaeology 10 Historical development 12 Spatial Analysis 15 Special features of the area 16 Views 16 Building types 16 University colleges 19 Boundary treatments 22 Building styles, materials and colours 23 Listed buildings 25 Significant non-listed buildings 30 Listed parks and gardens 33 Summary 33 Character areas 34 Norham Manor 34 Park Town 36 Bardwell Estate 38 Kingston Road 40 St Margaret’s 42 251 Banbury Road 44 North Parade 46 Lathbury and Staverton Roads 49 Opportunities for enhancement and change 51 Designation 51 Protection for unlisted buildings 51 Improvements in the Public Domain 52 Development Management 52 Non-residential use and institutionalisation large houses 52 SOURCES 53 APPENDICES 54 APPENDIX A: MAP INDICATING CHARACTER AREAS 54 APPENDIX B: LISTED BUILDINGS 55 APPENDIX C: LOCALLY SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS 59 252 North Oxford Victorian Suburb Conservation Area SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE This Conservations Area’s primary significance derives from its character as a distinct area, imposed in part by topography as well as by land ownership from the 16th century into the 20th century. At a time when Oxford needed to expand out of its historic core centred around the castle, the medieval streets and the major colleges, these two factors enabled the area to be laid out as a planned suburb as lands associated with medieval manors were made available. This gives the whole area homogeneity as a residential suburb. -

Oxford University's Bodleian Library Buildings

international · peer reviewed · open access From Bodleian to Idea Stores: The Evolution of English Library Design Rebecca K. Miller MSLS candidate School of Information and Library Science University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States Library Student Journal, January 2008 Abstract Library architecture, along with planning and design, is a significant consideration for librarians, architects, and city and institutional planners. Meaningful library architecture and planning has a history as old and rich as the very idea of libraries themselves, and can provide insight into the most dynamic library communities. This essay examines England’s history of library architecture and what it reveals, using three specific institutions to document the evolution of library design, planning, and service within a single, national setting. Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, the British Library, and the Idea Stores of London’s Tower Hamlets Borough represent— respectively, the past, present, and future of library architecture and design in England. The complex tension between rich tradition and cutting-edge innovation within England’s libraries and surrounding communities exposes itself through the changing nature of English library architecture, ultimately revealing the evolution of a national attitude concerning libraries and library service for the surrounding communities. Introduction Meaningful library architecture and planning has a long and complex history, and has the power to provide insight into the most dynamic library communities. There exists perhaps no better example of this phenomenon than the libraries of England; this country has a rich history of library architecture and continues to lead the way in library technology and innovation. -

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 3

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 3 On foot from Catte Street to Parson’s Pleasure by Malcolm Graham © Oxford Preservation Trust, 2015 This is a fully referenced text of the book, illustrated by Edith Gollnast with cartography by Alun Jones, which was first published in 2015. Also included are a further reading list and a list of common abbreviations used in the footnotes. The published book is available from Oxford Preservation Trust, 10 Turn Again Lane, Oxford, OX1 1QL – tel 01865 242918 Contents: Catte Street to Holywell Street 1 – 8 Holywell Street to Mansfield Road 8 – 13 University Museum and Science Area 14 – 18 Parson’s Pleasure to St Cross Road 18 - 26 Longwall Street to Catte Street 26 – 36 Abbreviations 36 Further Reading 36 - 38 Chapter 1 – Catte Street to Holywell Street The walk starts – and finishes – at the junction of Catte Street and New College Lane, in what is now the heart of the University. From here, you can enjoy views of the Bodleian Library's Schools Quadrangle (1613–24), the Sheldonian Theatre (1663–9, Christopher Wren) and the Clarendon Building (1711–15, Nicholas Hawksmoor).1 Notice also the listed red K6 phone box in the shadow of the Schools Quad.2 Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, architect of the nearby Weston Library, was responsible for this English design icon in the 1930s. Hertford College occupies the east side of Catte Street at this point, having incorporated the older buildings of Magdalen Hall (1820–2, E.W. Garbett) and created a North Quad beyond New College Lane (1903–31, T.G. -

The Clarendon Building Conservation Plan

The Clarendon Building The Clarendon Building, OxfordBuilding No. 1 144 ConservationConservation Plan, April Plan 2013 April 2013 Estates Services University of Oxford April 2013 The Clarendon Building, Oxford 2 Conservation Plan, April 2013 THE CLARENDON BUILDING, OXFORD CONSERVATION PLAN CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Purpose of the Conservation Plan 7 1.2 Scope of the Conservation Plan 8 1.3 Existing Information 9 1.4 Methodology 9 1.5 Constraints 9 2 UNDERSTANDING THE SITE 13 2.1 History of the Site and University 13 2.1.1 History of the Bodleian Library complex 14 2.2 History of the Clarendon Building 16 3 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CLARENDON BUILDING 33 3.1 Significance as part of the City Centre, Broad Street, Catte Street, and the 33 Central (City and University) Conservation Area 3.2 Significance as a constituent element of the Bodleian Library complex 35 3.3 Architectural Significance 36 3.3.1 Exterior Elevations 36 3.3.2 Internal Spaces 39 3.3.2.1 The Delegates’ Room 39 3.3.2.2 Reception 40 3.3.2.3 Admissions Office 41 The Clarendon Building, Oxford 3 Conservation Plan, April 2013 3.3.2.4 The Vice-Chancellor’s Office 41 3.3.2.5 Personnel Offices 43 3.3.2.6 Staircases 44 3.3.2.7 First-Floor Spaces 45 3.3.2.8 Second-Floor Spaces 47 3.3.2.9 Basement Spaces 48 3.4 Archaeological Significance 48 3.5 Historical and Cultural Significance 49 3.6 Significance of a functioning library administration building 49 4 VULNERABILITIES 53 4.1 Accessibility 53 4.2 Maintenance 54 4.2.1 Exterior Elevations and Setting 54 4.2.2 Interior Spaces 55 5 CONSERVATION -

The Career Choices of the Victorian Sculptor

The Career Choices of the Victorian Sculptor: Establishing an economic model for the careers of Edward Onslow Ford and Henry Hope- Pinker through their works Department of History of Art University of Leiden Alexandra Nevill 1st reader Professor Jan Teeuwisse S1758829 2nd reader Professor CJ Zijlmans [email protected] Masters in Design and Decorative Arts 11 November 2016 (18,611 words) 1 The career choices of Victorian sculptors: Edward Onslow Ford and Henry Hope-Pinker Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1 Networking: it pays to stay in touch. ......................................................................................... 12 Apprenticeships and the early years: ......................................................................................................... 13 The Royal Academy and the Mass Media: ................................................................................................. 17 The Art Workers Guild: friends and influence: ...................................................................................... -

Booklet Final 0.Pdf

POISON, PERSUASION, AND PANACEAS From poison pigments to hypnotic cures, this conference explores the many political and cultural imperatives that have informed scientific practice throughout history. While Oh and Fitzpatrick explore the expansion of empire, Canepa and Sinclair explore the expansion of waistlines. Müller uncovers the forgotten impostures of William Morris, while Hunkler and Bonney examine the medical and political importance of forgetting. These papers and others navigate the disputed relationship between science and society, investing the role of science in the construction of gender, race, and empire. The broad array of topics presented today is proof of the continuing intrigue of past, present, and future science, which has been used alternately to obscure, to elucidate, and to alter political life. Was Byron anorexic? Has science fiction influenced perceptions of virtual technology? Did a jellyfish substantiate Spencer’s evolutionary theory? These and other questions continue to fascinate and baffle today’s speakers. Poisons, Persuasion, and Panaceas Postgraduate Conference 6 June 2014 09:55-10:00 Introduction: Erica Charters, Associate Professor of the History of Medicine, Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine 10:00-11:30 Part I - Perceptions of Dangers in Art and Technology Amélie Müller ‘The art of selling green poison in Britain: The arsenical wallpapers of William Morris, 1855-1896’ Evan Bonney ‘Wondrous results, dangerous consequences: Hypnotism in Britain, 1890-1913’ John Lidwell-Durnin ‘Medusae, the mental, -

Local Heroes Awardees

October 2008 2010 Anniversary Programme Local Heroes awardees Guernsey heroes of the Royal Society Grosvenor Museum Miscellaneous Fellows Chester Friends of the Priaulx Library Guernsey Eddington. The universe and beyond Arthur Eddington FRS Constructing the Heavens: the Bath astronomers Kendal Museum Caroline Herschel & William Herschel FRS Cumbria Herschel Museum of Astronomy Bath Close encounters with jelly fish, bi-planes and Dartmoor Star gazing: Admiral Smyth's celestial Frederick Stratten Russell FRS observations Marine Biological Association William Henry Smyth FRS Plymouth Cecil Higgins Art Gallery & Bedford Museum Bedford Mary Anning - the geological lioness of Lyme Regis Cornelius Vermuyden's fantastic feat and the Mary Anning continuous battle to maintain Fenland drainage Lyme Regis Museum Cornelius Vermuyden FRS Dorset Prickwillow Drainage Engine Museum Ely, Cambridgeshire The Bailey bridge- A tribute to Sir Donald Bailey Donald Bailey The science of sound Redhouse Museum & Gardens JW Strutt PRS Christchurch Whipple Museum of the History of Science Dorset Cambridge Barnes Wallis- The Yorkshire connection and Trilobites, toadstone and time beyond John Whitehurst FRS Barnes Wallis FRS Congleton Museum East Riding of Yorkshire Museum Service Cheshire Beverley Museum display and events to celebrate John No flies on him: the multi talented Professor Ray in the 21st Century Newstead John Ray FRS Robert Newstead FRS Braintree District Museum 1 Essex Fantastic Mr Ferranti Star gazing Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti FRS James Pound FRS -

Directions to Owls from Westgate Car Park Supplementum

Harry Potter Places Book TWO WCP to OWLs Directions Supplementum www.HarryPotterPlaces.com Directions from Westgate Car Park [WCP] to the 1 Bodleian Ticket Office MAP ONE Please Note: The map images used to create Harry Potter Places Directions Maps were obtained from Google Maps UK—© 2011 Google. Walk to the Bodleian Ticket Office Point A on Map One and on the Oxford Wizarding Locations Map WCP to the Bodleian Library is a 20 minute walk. Exit the WCP to the west. Depending on where you park, you’ll be exiting onto Norfolk Street or Castle Street. ♦ Turn right and walk north until Castle Street ends. ♦ Turn right and walk east on Bonn Square (street), continuing as it becomes Queen Street. When you reach the intersection of Saint Aldate’s (street) on your left and Cornmarket Street (on your right), Queen Street becomes High Street. ♦ Cross to the north side of High Street at this intersection. Continue east on the north side of High Street until you reach Catte Street. ♦ Turn left and walk north. After passing the Radcliffe Camera building (on your left), watch on your left for the Bodleian Library Great Gate. Alternate Route If you didn’t find the Westgate Car Park public toilet, after crossing to the north side of High Street (above) walk north on Cornmarket Street to Market Street. ♦ Turn right and watch on your right for the public toilet between the Wagamama noodle restaurant and the Covered Market entrance. When finished, turn right to resume walking east on Market Street. When you reach the place where Market Street turns north and becomes Turl Street, look straight ahead for Brasenose Lane, a pedestrian walkway.