Oxford Heritage Walks Book 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Letter Template

North Area Committee 4th March 2010 Central South and West Area Committee 9th March 2010 Strategic Development Control Committee 25th March 2010 Application Number: 09/02466/FUL, 09/02467/LBD, 09/02468/CAC Decision Due by: 10th February 2010 Proposal: 09/02466/FUL: Demolition of buildings on part of Acland site, retaining the main range of 25 Banbury Road, erection of 5 storey building fronting Banbury Road and 4 storey building fronting Woodstock Road to provide 240 student study bedrooms, 6 fellows flats, 3 visiting fellows flats with associated teaching office and research space and other ancillary facilities. Alteration to existing vehicular accesses to Banbury Road and Woodstock Road, provision of 27 parking spaces (including 4 disabled spaces) and 160 cycle parking spaces, recycling and waste bin storage, substation and including landscaping scheme. 09/02467/LBD: Listed Building Demolition. Demolition of buildings on part of Acland site, retaining the main range of 25 Banbury Road, (demolishing service range and later additions). Erection of extensions as part of a new college quad to provide 240 student study bedrooms, 6 fellows flats, 3 visiting fellows flats with associated teaching, office and research space and other ancillary facilities. External alterations including the removal of a chimney stack, underpinning and replacement of roof over staircase. Internal alterations to remove modern partitions, form new doorways, install en-suite facilities and reinstate staircase to 3rd floor. 09/02468/CAC: Conservation Area Consent. Demolition of 46 Woodstock Road. Site Address: Keble College Land At The Former Acland Hospital And 46 Woodstock Road 25 Banbury Road, (Site Plan - Appendix 1) Ward: North Agent: John Philips Planning Applicant: Keble College Consultancy REPORT Recommendation: Application for Planning Permission The North Area and Central South and West Area Committees are recommended to support the application for planning permission. -

9-10 September 2017

9-10 September 2017 oxfordpreservation.org.uk Contents and Guide A B C D E F G A44 A34 To Birmingham (M40) 1 C 1 h d a To Worcester and Northampton (A43) oa d R n l to i Lin n g t B o a n P&R n R b o P&R Water Eaton W u a r d Pear o y N Contents Guide o R o & d Tree o r s d t a a o h t R o n d o m ns c awli k R o Page 2 Page 12 – Thursday 7 Sept – City centre map R o A40 o r a R Oxford To Cheltenham d o a 2 d 2 Page 4 – Welcome Page 13 – Friday 8 Sept W d oodst A40 Roa et’s r Banbur arga Page 5 – Highlights - Hidden Oxford Page 15 – Saturday 9 Sept M St ock R A34 y R oad M arst anal oad Page 7 Pages 20 & 21 To London (M40) – Highlights - Family Fun – OPT – what we do ace on R d C n Pl A40 W so or wn en Oxford a To B oad xf lt ark O P o City Page 8 Page 29 n ad – OPT venues – Sunday 10 Sept o S R d n a F P&R Centre oad t o o y P&R r d R fi e rn Seacourt a ad m e ondon R e F o a L Thornhill ry R h l t r 3 rbu No d 3 e R Page 9 t – OPT member only events an o C a d B r Botley Road e a rad d ad a m o th P k R Abingdon R r o No Cric A4142 r e I ffley R R Co o wley R a d s oad oad d n oad oa de R ar A420 rd G Red – OPT venues, FF – Family friendly, R – Refreshments available, D – Disabled access, fo am To Bristol ck rh Le No ad (D) – Partial disabled access Ro 4 ton P&R 4 ing Bev Redbridge A34 To Southampton For more specific information on disabled access to venues, please contact OPT or the venue. -

SPATIAL CHANGES in an OXFORD PUBLIC ASYLUM YUXIN PENG1 Introduction Existing Anthropological Literature on Mental Health in Publ

SPATIAL CHANGES IN AN OXFORD PUBLIC ASYLUM YUXIN PENG1 Abstract This article examines spatial changes at Littlemore hospital in Oxford between 1846 and 1956, the period since its foundation as a Victorian public asylum to the very last years before a radical psychiatric reform was implemented. I propose to see the asylum and later hospital spaces of Littlemore as being bodily sensed and co-productive with social processes. Specifically, I discuss the entanglement of these spaces with three factors: (panoptical) control, considerations of cost, and residents’ comfort. With emphases on residents’ bodily well-being and experiences, I aim to present a dynamic account of this part of the history of institutionalized mental health. Introduction Existing anthropological literature on mental health in public institutions has a strong interest in power. As noted by Lorna Rhodes in her ethnography of maximum-security prisons in the USA, although she does not see her project as ‘an application of Foucault to prisons’, she has found it impossible not to address the distinction between reason and madness and the phenomenon of panoptical observation (Rhodes 2004: 15). Regarding the specificity of her research topic, which is about severe mental health in the most secure prisons in America, an orientation towards these themes is both reasonable and suitable. Rhodes’ later work on psychiatric citizenship looks at it from the inmate’s perspective. By analysing the interviews, letters, poems, and drawings she obtained from Sam, an inmate whose mental health worsened in this supermax prison, Rhodes discusses how psychiatric citizenship is formed in a strictly controlled institutional setting by one’s attachment to a psychological report made on one’s case, which also led Sam to a new way of making sense of his own history (Rhodes 2010). -

Quality As a Space to Spend Time Proximity and Quality of Alternatives Active Travel Networks Heritage Concluaiona Site No. Site

Quality as a space to spend Proximity and quality of Active travel networks Heritage Concluaiona time alternatives GI network (More than 1 of: Activities for different ages/interests Where do spaces currently good level of public use/value, Within such as suitability for informal sports and play/ provide key walking/cycling links? Biodiversity, cta, sports, Public Access Visual interest such as variety and colour Number of other facilities Which sites do or Agricultural Active Travel Networks curtilage/a Historic Local Landscape value variety of routes/ walking routes Level of anti-social behaviour (Public rights of way SSS Conservation Ancient OC Flood Zone In view allotments, significant visual Individual GI Site No. Site Name (Unrestricted, Description of planting, surface textures, mix of green Level of use within a certain distance that could best provide Land SAC LNR LWS (Directly adjacent or djoining In CA? park/garde Heritage Landscape Type of open space in Local Value Further Details/ Sensitivity to Change Summary Opportunities /presence, quality and usage of play and perceptions of safety National Cycle Network I Target Areas Woodlands WS (Worst) cone? interest or townscape protections Limited, Restricted) and blue assets, presence of public art perform the same function alternatives, if any Classification containing a network) listed n Assets this area equipment/ Important local connections importance, significant area of building? presence of interactive public art within Oxford) high flood risk (flood zone 3)) Below ground Above ground archaeology archaeology Areas of current and former farmland surrounded by major roads and edge of city developments, such as hotels, garages and Yes - contains two cycle Various areas of National Cycle Routes 5 and 51 Loss of vegetation to development and Northern Gateway a park and ride. -

Uplands 06.01.2020

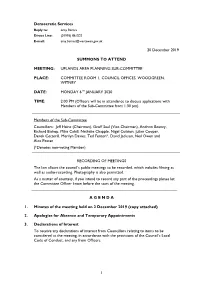

Democratic Services Reply to: Amy Barnes Direct Line: (01993) 861522 E-mail: [email protected] 20 December 2019 SUMMONS TO ATTEND MEETING: UPLANDS AREA PLANNING SUB-COMMITTEE PLACE: COMMITTEE ROOM 1, COUNCIL OFFICES, WOODGREEN, WITNEY DATE: MONDAY 6TH JANUARY 2020 TIME: 2.00 PM (Officers will be in attendance to discuss applications with Members of the Sub-Committee from 1:30 pm) Members of the Sub-Committee Councillors: Jeff Haine (Chairman), Geoff Saul (Vice-Chairman), Andrew Beaney, Richard Bishop, Mike Cahill, Nathalie Chapple, Nigel Colston, Julian Cooper, Derek Cotterill, Merilyn Davies, Ted Fenton*, David Jackson, Neil Owen and Alex Postan (*Denotes non-voting Member) RECORDING OF MEETINGS The law allows the council’s public meetings to be recorded, which includes filming as well as audio-recording. Photography is also permitted. As a matter of courtesy, if you intend to record any part of the proceedings please let the Committee Officer know before the start of the meeting. _________________________________________________________________ A G E N D A 1. Minutes of the meeting held on 2 December 2019 (copy attached) 2. Apologies for Absence and Temporary Appointments 3. Declarations of Interest To receive any declarations of interest from Councillors relating to items to be considered at the meeting, in accordance with the provisions of the Council’s Local Code of Conduct, and any from Officers. 1 4. Applications for Development (Report of the Business Manager – Development Management – schedule attached) Purpose: To consider applications for development, details of which are set out in the attached schedule. Recommendation: That the applications be determined in accordance with the recommendations of the Business Manager – Development Management. -

Oxford Audio Admissions Tours

d on R ght O rou x elb f B o C r ad o h d n R o B N a C rt a e o r l a v n a r b t n b t S h u a u m r l r y y o R o North Mead R o r o R a a o d d a W d o d o a Ro d ton South Mead s in t L o c k R o a d ad n Ro inso Rawl ad d Ro stea Pol oad ll R ad we t’s Ro ard rgare B St Ma ad t’s Ro rgare St Ma Road ad on Ro F d m y rn a aW d h F oa r e R o a y N l ur d r rb n eW nt R b Ca o i o n a r d c o d h u oa e R g k s ic h r t C R e r d W R o o o a s d d d en oa s d R t ar rd o G fo c m ck k a e rh L R No o a k d d al on R W ingt rth Bev No W T a d h l oa o t ’s R r o ard n ern n St B W R P University a i S t l v t e a k r O e re r r e t Parks a e S k k C t n s W h io e at R a rw rv o lk e e a ll bs Oxford Audio Admissionsd Tours - Green Route - Life Sciences O Time: 60-90 minutes, Distance:B 3.2 km/2 miles a n alk b W outh t u S S r m y a h R 18 n o ra C a d d 19 e R l Keb B la d Great c oa 20 St k 17 R n h rks Meadow R o a a d ll P S o n R h Sports O e d t t ge r 1 2 16 u la o C x S C r Ground r f le m M o t u o C D it se s a L u a r s u n M d n d oa R d a R s l o m C S e a a t r l d a e d n n e a t R Sports W l 15 o a W a Ground y N d ad elson Richmond R d o S a R t S r O 3 4 o l P n xf t t a o a o t S M r e G r Wod rcester n C re t k t i s a S CollegeS J l n o e R na t l r o P h s o Spod rtsa e ’ a n t e n e h d 12 r t a Ground Cl S 14 t t a r re e Jow G e ett W t alk 11 M 7 M reet a 6 yw ont St g Hol ell Stree a t Beaum d C 10 g R E a 5 a 13 W e d a l t w s e a t l e t n e e l t s e e y S e S t tr n S t t ad R ro L B 8 Bus S o o t -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Samuel Lipscomb Seckham

Samuel Lipscomb Seckham By PETER HOWELL l TIL recently the name of Samuel Lipscomb Seckham was fairly widely U known in Oxford as that of the architect of Park Town. A few other facts, such as that he was City Surveyor, were known to the cognoscenti. No-one, however, had been able to discover anything significant about his background, let alone what happened to him after he built the Oxford Corn Exchange in 1861-2. In '970 a fortunate chance led to the establishment of contact with Dr. Ann Silver, a great-granddaughter of Seckham, and as a result it has been po ible to piece together the outline ofhis varied career.' He was born on 25 October ,827,' He took his names from his grandparents, Samuel Seckham (1761-1820) and Susan Lipscomb (d. 18'5 aged 48).3 His father, William ('797-,859), kept livery stables at 20 Magdalen Street, Oxford,. and prospered sufficiently to retire and farm at Kidlington.5 The family came from Devon, where it is aid that Seccombes have occupied Seccombe Farm at Germans week, near Okehampton, since Saxon limes. Seccombes are still living there, farming. It is thought that Seckllam is the earlier spelling, but tombstones at Germansweek show several different versions. 6 It is not known how the family reached Oxford, but Samuel Lipscomb Seckham's great-grandmother Elizabeth was buried at St. Mary Magdalen in 1805.7 His mother was Harriett Wickens (1800-1859). Her grandfather and father were both called James, which makes it difficult to sort out which is which among the various James W;ckens' recorded in I The fortunate chance occurred when Mrs. -

Strategy 2018-2022

BODLEIAN LIBRARIES STRATEGY 2018–2022 Sharing knowledge, inspiring scholarship Advancing learning, research and innovation from the heart of the University of Oxford through curating, collecting and unlocking the world’s information. MESSAGE FROM BODLEY’S LIBRARIAN The Bodleian is currently in its fifth century of serving the University of Oxford and the wider world of scholarship. In 2017 we launched a new strategy; this has been revised in 2018 to be in line with the University’s new strategic plan (www.ox.ac.uk/about/organisation/strategic-plan). This new strategy has been formulated to enable the Bodleian Libraries to achieve three key aims for its work during the period 2018-2022, to: 1. help ensure that the University of Oxford remains at the forefront of academic teaching and research worldwide; 2. contribute leadership to the broader development of the world of information and libraries for society; and 3. provide a sustainable operation of the Libraries. The Bodleian exists to serve the academic community in Oxford and beyond, and it strives to ensure that its collections and services remain of central importance to the current state of scholarship across all of the academic disciplines pursued in the University. It works increasingly collaboratively with other parts of the University: with college libraries and archives, and with our colleagues in GLAM, the University’s Gardens, Libraries and Museums. A key element of the Bodleian’s contribution to Oxford, furthermore, is its broader role as one of the world’s leading libraries. This status rests on the depth and breadth of its collections to enable scholarship across the globe, on the deep connections between the Bodleian and the scholarly community in Oxford, and also on the research prowess of the libraries’ own staff, and the many contributions to scholarship in all disciplines, that the library has made throughout its history, and continues to make. -

Hertford College

HERTFORD COLLEGE COLLEGE HANDBOOK 2020–21 1 1. OVERVIEW The College Handbook is published annually, and the most recent version is always available on the college website and intranet. It contains vital information, so you should keep it as a reference guide to your life at Hertford. This handbook should be read in the context of the most up-to-date public health advice issued in light of the ongoing global coronavirus (covid-19) pandemic. Any new measures to be applied on College sites and beyond which arise from University, College and general public health guidance will always supersede, as applicable, any relevant sections below. University information for students: https://www.ox.ac.uk/coronavirus. College information for students: https://www.hertford.ox.ac.uk/intranet. NHS advice on coronavirus: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/. If this guide does not answer your query, please contact one of the following by email: for academic matters, including tuition, the Senior Tutor; on matters of finance or domestic services, the Bursar; for welfare matters the Dean, Chaplain, Nurses, or Junior Deans; on matters relating to College regulations, the Dean or Student Conduct Officer. The Academic Office is a useful first point of contact, open Monday to Friday, 9am – 5pm. 2 CONTENTS 1. OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. HISTORY OF THE COLLEGE ......................................................................................... -

Brookes Goes Walking : a Guide to the Route

Brookes Goes Walking : A Guide to the Route Starting from Brookes Students' Union: Follow the path to the bridge over the main road. This bridge was built in 1877 to link the two parts of the large Morrell estate on each side of the road below. The road was originally the Stokenchurch Turnpike constructed in 1775. Don't cross the bridge, instead walk down the road and turn right into Headington Park. The park was originally part of the ornamental garden belonging to the Hall where the Morrells lived. Turn left out of the park and cross the road with care. Take the path opposite down to the river. The large new stone building is the new Oxford University Centre for Islamic Studies. The building on the right by the River Cherwell was once the King’s Mill. It dates from the Middle Ages but stopped working in 1832. Turn right along the path. This area is called Mesopotamia, from the Greek for “between two rivers”. The original two rivers were the Euphrates and the Tigris so this Oxford version is on a slightly smaller scale! Along this stretch you will see many pollarded willows, trees which have been cut at about head height. The regrowth was used by local people for poles for building and fencing. Pollarding also prevents the trees from splitting when they get top heavy. On a map of 1887 a ferry was shown to operate here. The fields on both sides are often quite wet. Several fields you will see along the route contain rushes and sedges showing the marshy ground. -

Parks Road, Oxford

Agenda Item 5 West Area Planning Committee 8 June 2011 Application (i): 10/03210/CAC Numbers: (ii): 10/03207/FUL Decision Due by: 23 February 2011 Proposals: (i): 10/03210/CAC : Removal of existing ornamental gates and sections of railings fronting Lindemann building and to University parks. (ii): 10/03207/FUL : Demolition of former lodge building and removal of temporary waste stores. Erection of new physics research building on 5 levels above ground plus 2 basement levels below with 3 level link to Lindemann building. Creation of landscaped courtyard to South of new building and cycle parking to North. Re-erection of Lindemann gates to repositioned entrance to University Parks and of University Park gates to new entrance further north opposite Dept of Materials. Re-alignment of boundary railings. Site Address: Land adjacent to the Clarendon Laboratory, Parks Road, Appendix 1 . Ward: Holywell Ward Agent: DPDS Consulting Group Applicant: The University Of Oxford Recommendations: Committee is recommended to grant conservation area consent and planning permission, subject to conditions. Reasons for Approval. 1. The Council considers that the proposal accords with the policies of the development plan as summarised below. It has taken into consideration all other material matters, including matters raised in response to consultation and publicity. Any material harm that the development would otherwise give rise to can be offset by the conditions imposed. 2. The Council considers that the proposal, subject to the conditions imposed, would accord with the special character and appearance of the conservation areas it adjoins. It has taken into consideration all other material matters, including matters raised in response to consultation and publicity.