Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAREWELL the TRUMPETS an Imperial Retreat Read by Roy Mcmillan

NON- FICTION UNABRIDGED JanJan MorrisMorris FAREWELL THE TRUMPETS An Imperial Retreat Read by Roy McMillan PAX BRITANNICA • 3 NA0038 Farewell the Trumpets (U) booklet.indd 1 30/09/2011 14:38 CD 1 1 An Introduction… 3:26 2 Farewell the Trumpets… 4:39 3 2. My people… 5:56 4 3. The origins… 4:15 5 4. They were uniquely… 5:30 6 5. There were few... 5:13 7 6. Still the public... 4:26 8 Chapter 2: An Explorer in Diffi culties 7:20 9 2. Britain’s was not... 7:04 10 3. The day after... 6:29 11 4. This engaging... 6:43 12 5. The British also... 6:39 13 Chapter 3: Following the Flags 1:17 14 2. There was hardly... 4:17 15 3. There was no escaping it... 3:00 16 4. And if to the public... 2:47 Total Time on CD 1: 79:11 2 NA0038 Farewell the Trumpets (U) booklet.indd 2 30/09/2011 14:38 CD 2 1 Languages especially... 1:27 2 5. Behind this... 4:29 3 For by now... 5:51 4 6. Yet if there was... 5:08 5 7. It was too late anyway 7:34 6 8. Chamberlain never... 0:52 7 Chapter 4: The Life We Always Lead 3:05 8 2. The British and the Boers... 5:49 9 3. On the face of it... 5:17 10 4. As Buller sailed... 5:28 11 5. Let us peer... 6:31 12 6. For a very different battlefi eld.. -

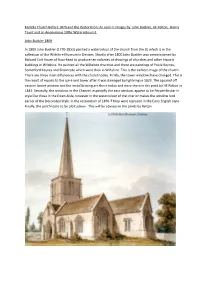

Kemble Church Before 1876 and the Restoration: As Seen in Images by John Buckler, HE Relton, Henry Taunt and an Anonymous 19Thc Watercolourist

Kemble Church Before 1876 and the Restoration: As seen in images by John Buckler, HE Relton, Henry Taunt and an Anonymous 19thc Watercolourist. John Buckler 1809 In 1809 John Buckler (1770-1851) painted a watercolour of the church from the SE which is in the collection of the Wiltshire Museum in Devizes. Shortly after 1800 John Buckler was commissioned by Richard Colt Hoare of Stourhead to produce ten volumes of drawings of churches and other historic buildings in Wiltshire. He painted all the Wiltshire churches and there are paintings of Poole Keynes, Somerford Keynes and Shorncote which were then in Wiltshire. This is the earliest image of the church. There are three main differences with the church today. Firstly, the tower windows have changed. This is the result of repairs to the spire and tower after it was damaged by lightning in 1823. The squared off eastern lancet window and the metal bracing are there today and were there in the print by HE Relton in 1843. Secondly, the windows in the Chancel, especially the east window, appear to be Perpendicular in style like those in the Ewen Aisle, however in the watercolour of the interior makes the window look earlier of the Decorated Style. In the restoration of 1876-7 they were replaced in the Early English style. Finally, the porch looks to be a bit askew. This will be obvious in the prints by Relton. H. E. Relton 1843 These two prints are from ‘Sketches of Churches, with Short Descriptions’ by H. E. Relton; London (1843). He visited quite a few churches in Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Berkshire and he wrote a few notes on each of the churches. -

Studental Dental Practice

brookesunion.org.ukbrookesunion.org.uk | fb.com/BrookesUnion | fb.com/BrookesUnion | | @BrookesUnion @brookesunion Advertisement STUDENTAL DENTAL PRACTICE CONTENTs Studental is currently accepting new nhs Patients! • e re se of e r en rcice i Introduction qualified, caring and respectful team of dentists 4-5 and staff. Areas of Oxford • e re oce on e for Brookes 7–8 Headington Campus in the Colonnade building. Sites to see and things to do • We are taking on new NHS and private patients, 10-17 even if only for short term periods. • We can cater for the families of students as well as Events students themselves. 18–19 • Even if you have a dentist elsewhere (back home), Food and drink you are still able to come and see us (you do not ind s n ms 20-25 need to deregister from your other dental surgery). for Brookes Clubbing guide • Some of you might be eligible for exemption from Headington Campus, 26-27 en crges ese enuire uen Colonnade Building, Getting around reception. 3rd Floor, OX3 0BP 30-31 • We are able to provide emergency appointments. • We have an Intra-oral camera for a closer view of Where to go shopping dental problems. We can also provide wisdom 32-35 eebring our t er tooth extractions, specialist periodontal treatment, Sustainability specialist prosthodontic treatments, implants, 36-39 tooth whitening, specialist root canal treatments with our microscope, and invisalign treatments. 40-41 Staying safe State of the art dental care is now 42-46 Welfare within everyone’s reach 47-52 Directory [email protected] intments esi n r site While care has been taken to ensure that all information is correct at the time of going to print, we do www.studental.co.uk not assume responsibility for any errors. -

Medal Y Cymmrodorion 2016 / the Cymmrodorion Medal 2016

185 MEDAL Y CYMMRODORION 2016 / THE CYMMRODORION MEDAL 2016 Presented to Jan Morris 9 October 2016 The Welsh historian, author, and travel writer, Jan Morris CBE FRSL FLSW, who celebrated her ninetieth birthday in October 2016, was awarded the Medal of the Cymmrodorion Society during a ceremony held at the Tŷ Newydd Writing Centre in Llanystumdwy, near Criccieth, on Sunday 9 October 2016. The Medal was awarded ‘for her distinguished contribution to literature and to Wales’. Following an introduction by the Society’s President, Professor Prys Morgan, the Presentation Address was given by Professor Jason Walford Davies of the School of Welsh at Bangor University, who spoke of Jan Morris’s immense contribution to Welsh writing in English and of the value of her work and its cultural significance in Welsh, British, and international contexts. Jan Morris, who lives in Llanystumdwy with her partner, Elizabeth, has been writing and publishing books since the 1950s. She is known particularly for the Pax Britannica trilogy (1968–78), a history of the British Empire; for various books on Wales, including Wales: Epic Views of a Small Country (first published as The Matter of Wales in 1984); and for portraits of cities, notably Oxford, Venice, Trieste, Hong Kong, and New York. Jan Morris has received honorary doctorates from the University of Wales and the University of Glamorgan, is an Honorary Fellow of Christ Church, Oxford, and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and of the Learned Society of Wales. She was appointed CBE in 1999 and, in 2005, she was awarded the Golden PEN Award by English PEN for ‘a Lifetime’s Distinguished Service to Literature’. -

Oxford Audio Admissions Tours

d on R ght O rou x elb f B o C r ad o h d n R o B N a C rt a e o r l a v n a r b t n b t S h u a u m r l r y y o R o North Mead R o r o R a a o d d a W d o d o a Ro d ton South Mead s in t L o c k R o a d ad n Ro inso Rawl ad d Ro stea Pol oad ll R ad we t’s Ro ard rgare B St Ma ad t’s Ro rgare St Ma Road ad on Ro F d m y rn a aW d h F oa r e R o a y N l ur d r rb n eW nt R b Ca o i o n a r d c o d h u oa e R g k s ic h r t C R e r d W R o o o a s d d d en oa s d R t ar rd o G fo c m ck k a e rh L R No o a k d d al on R W ingt rth Bev No W T a d h l oa o t ’s R r o ard n ern n St B W R P University a i S t l v t e a k r O e re r r e t Parks a e S k k C t n s W h io e at R a rw rv o lk e e a ll bs Oxford Audio Admissionsd Tours - Green Route - Life Sciences O Time: 60-90 minutes, Distance:B 3.2 km/2 miles a n alk b W outh t u S S r m y a h R 18 n o ra C a d d 19 e R l Keb B la d Great c oa 20 St k 17 R n h rks Meadow R o a a d ll P S o n R h Sports O e d t t ge r 1 2 16 u la o C x S C r Ground r f le m M o t u o C D it se s a L u a r s u n M d n d oa R d a R s l o m C S e a a t r l d a e d n n e a t R Sports W l 15 o a W a Ground y N d ad elson Richmond R d o S a R t S r O 3 4 o l P n xf t t a o a o t S M r e G r Wod rcester n C re t k t i s a S CollegeS J l n o e R na t l r o P h s o Spod rtsa e ’ a n t e n e h d 12 r t a Ground Cl S 14 t t a r re e Jow G e ett W t alk 11 M 7 M reet a 6 yw ont St g Hol ell Stree a t Beaum d C 10 g R E a 5 a 13 W e d a l t w s e a t l e t n e e l t s e e y S e S t tr n S t t ad R ro L B 8 Bus S o o t -

Togas Gradui Et Facultati Competentes: the Creation of New Doctoral Robes at Oxford, 1895–1920

Transactions of the Burgon Society Volume 10 Article 4 1-1-2010 Togas gradui et facultati competentes: The Creation of New Doctoral Robes at Oxford, 1895–1920 Alan J. Ross Wolfson College Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/burgonsociety Recommended Citation Ross, Alan J. (2010) "Togas gradui et facultati competentes: The Creation of New Doctoral Robes at Oxford, 1895–1920," Transactions of the Burgon Society: Vol. 10. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2475-7799.1084 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Burgon Society by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transactions of the Burgon Society, 10 (2010), pages 47–70 Togas gradui et facultati competentes: The Creation of New Doctoral Robes at Oxford, 1895–1920 by Alan J. Ross 1. Introduction During the academic year 2009/10, 18,755 students in the United Kingdom completed a doctoral degree after either full- or part-time study.1 The vast majority of these doctorates were obtained by young researchers immediately after the completion of a first degree or master’s programme, and were undertaken in many cases as an entry qualification into the academic profession. Indeed, the PhD today is the sine qua non for embarkation upon an academic career, yet within the United Kingdom the degree itself and the concept of professionalized academia are less than a hundred years old. The Doctorate of Philosophy was first awarded in Oxford in 1920, having been established by statute at that university in 1917. -

MINUTES of the 84Th MEETING of AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD at the VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO on WEDNESDAY 27Th JANUARY 2016

MINUTES OF THE 84th MEETING OF AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD AT THE VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO ON WEDNESDAY 27th JANUARY 2016 Present: - Rupert Clark – Chairman & Treasurer Peter Cole - Secretary. 1. Chairman’s Report Copies of Nicholas Cooper’s Aynho book have become available for sale at £15. A visit to Rousham House suggested last year would have to be on a Sunday afternoon. Let Rupert know if you would like this to be arranged. 2. Secretary’s Report Rupert, Keith and Peter as representatives of the Cartwright Archive have met Sarah Bridges (Archivist) at the Northants Records Office to discuss the Archive’s conservation and future. Further updates once the Charity Committee has met in February. 3. “A History of the University of Oxford” by Alastair Lack Oxford is the third oldest university in Europe, behind Bologna in Italy and the Sorbonne in Paris. There were students in Oxford in the 1090s, but this was not under grad education, as we know it, more like private tutoring. Various people established “halls” (like a boarding house) around the Church of St Mary the Virgin. Students were between 12 and 15 years old, they drank, they gambled and as the untrained hall owners did the teaching they didn’t learn much. Little changed much until 1170 when King Henry II demanded that all English students at the Sorbonne should return to England as he was concerned about a brain drain. Oxford was the only established place of study for them to return to. In 1196, the first account of these academic halls was written by Geoffrey of Monmouth; he was a prominent intellect of the day and had visited Oxford to presented three lectures on law. -

Corpus Christi College the Pelican Record

CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LII December 2016 i The Pelican Record Editor: Mark Whittow Design and Printing: Lynx DPM Published by Corpus Christi College, Oxford 2016 Website: http://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk Email: [email protected] The editor would like to thank Rachel Pearson, Julian Reid, Joanna Snelling, Sara Watson and David Wilson. Front cover: Detail of the restored woodwork in the College Chapel. Back cover: The Chapel after the restoration work. Both photographs: Nicholas Read ii The Pelican Record CONTENTS President’s Report .................................................................................... 3 Carol Service 2015 Judith Maltby.................................................................................................... 12 Claymond’s Dole Mark Whittow .................................................................................................. 16 The Hallifax Bowl Richard Foster .................................................................................................. 20 Poisoning, Cannibalism and Victorian England in the Arctic: The Discovery of HMS Erebus Cheryl Randall ................................................................................................. 25 An MCR/SCR Seminar: “An Uneasy Partnership?: Science and Law” Liz Fisher .......................................................................................................... 32 Rubbage in the Garden David Leake ..................................................................................................... -

Hertford College

HERTFORD COLLEGE COLLEGE HANDBOOK 2020–21 1 1. OVERVIEW The College Handbook is published annually, and the most recent version is always available on the college website and intranet. It contains vital information, so you should keep it as a reference guide to your life at Hertford. This handbook should be read in the context of the most up-to-date public health advice issued in light of the ongoing global coronavirus (covid-19) pandemic. Any new measures to be applied on College sites and beyond which arise from University, College and general public health guidance will always supersede, as applicable, any relevant sections below. University information for students: https://www.ox.ac.uk/coronavirus. College information for students: https://www.hertford.ox.ac.uk/intranet. NHS advice on coronavirus: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/. If this guide does not answer your query, please contact one of the following by email: for academic matters, including tuition, the Senior Tutor; on matters of finance or domestic services, the Bursar; for welfare matters the Dean, Chaplain, Nurses, or Junior Deans; on matters relating to College regulations, the Dean or Student Conduct Officer. The Academic Office is a useful first point of contact, open Monday to Friday, 9am – 5pm. 2 CONTENTS 1. OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. HISTORY OF THE COLLEGE ......................................................................................... -

NORTH OXFORD VICTORIAN SUBURB CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Consultation Draft - January 2017

NORTH OXFORD VICTORIAN SUBURB CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Consultation Draft - January 2017 249 250 CONTENTS SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE 5 Reason for appraisal 7 Location 9 Topography and geology 9 Designation and boundaries 9 Archaeology 10 Historical development 12 Spatial Analysis 15 Special features of the area 16 Views 16 Building types 16 University colleges 19 Boundary treatments 22 Building styles, materials and colours 23 Listed buildings 25 Significant non-listed buildings 30 Listed parks and gardens 33 Summary 33 Character areas 34 Norham Manor 34 Park Town 36 Bardwell Estate 38 Kingston Road 40 St Margaret’s 42 251 Banbury Road 44 North Parade 46 Lathbury and Staverton Roads 49 Opportunities for enhancement and change 51 Designation 51 Protection for unlisted buildings 51 Improvements in the Public Domain 52 Development Management 52 Non-residential use and institutionalisation large houses 52 SOURCES 53 APPENDICES 54 APPENDIX A: MAP INDICATING CHARACTER AREAS 54 APPENDIX B: LISTED BUILDINGS 55 APPENDIX C: LOCALLY SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS 59 252 North Oxford Victorian Suburb Conservation Area SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE This Conservations Area’s primary significance derives from its character as a distinct area, imposed in part by topography as well as by land ownership from the 16th century into the 20th century. At a time when Oxford needed to expand out of its historic core centred around the castle, the medieval streets and the major colleges, these two factors enabled the area to be laid out as a planned suburb as lands associated with medieval manors were made available. This gives the whole area homogeneity as a residential suburb. -

London Metropolitan Archives Mayor's Court

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 MAYOR'S COURT, CITY OF LONDON CLA/024 Reference Description Dates COURT ROLLS Early Mayor's court rolls CLA/024/01/01/001 Roll A 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/002 Roll B 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/003 Roll C 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/004 Roll D 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/005 Roll E 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/006 Roll F 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/007 Roll G 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/008 Roll H 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/009 Roll I 1298 - 1307 1 roll Plea and memoranda rolls CLA/024/01/02/001 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1323-1326 Former Reference: A1A CLA/024/01/02/002 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1327-1336 A sample image is available to view online via the Player and shows an llustration of a pillory (membrane 16 on Mayor's Court Plea and Memoranda Roll). To see more entries please consult the entire roll at London Metropolitan Archives. Former Reference: A1B LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 MAYOR'S COURT, CITY OF LONDON CLA/024 Reference Description Dates CLA/024/01/02/003 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1332 Former Reference: A2 CLA/024/01/02/004 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1338-1341 Former Reference: A3 CLA/024/01/02/005 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1337-1338, Former Reference: A4 1342-1345 CLA/024/01/02/006 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1337-1339, Former Reference: A5 1341-1345 CLA/024/01/02/007 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1349-1350 Former Reference: A6 CLA/024/01/02/008 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1354-1355 12 April 1355 - Names of poulterers sworn to supervise the trade in Leaderhall, Poultry and St. -

Oxford University's Bodleian Library Buildings

international · peer reviewed · open access From Bodleian to Idea Stores: The Evolution of English Library Design Rebecca K. Miller MSLS candidate School of Information and Library Science University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States Library Student Journal, January 2008 Abstract Library architecture, along with planning and design, is a significant consideration for librarians, architects, and city and institutional planners. Meaningful library architecture and planning has a history as old and rich as the very idea of libraries themselves, and can provide insight into the most dynamic library communities. This essay examines England’s history of library architecture and what it reveals, using three specific institutions to document the evolution of library design, planning, and service within a single, national setting. Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, the British Library, and the Idea Stores of London’s Tower Hamlets Borough represent— respectively, the past, present, and future of library architecture and design in England. The complex tension between rich tradition and cutting-edge innovation within England’s libraries and surrounding communities exposes itself through the changing nature of English library architecture, ultimately revealing the evolution of a national attitude concerning libraries and library service for the surrounding communities. Introduction Meaningful library architecture and planning has a long and complex history, and has the power to provide insight into the most dynamic library communities. There exists perhaps no better example of this phenomenon than the libraries of England; this country has a rich history of library architecture and continues to lead the way in library technology and innovation.