The Flood of June 2013 in Germany: How Much Do We Know About Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

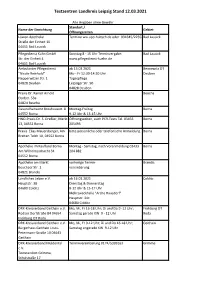

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 12.03.2021

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 12.03.2021 Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr Standort / Name der Einrichtung Gebiet Öffnungszeiten Löwen Apotheke Termine ww.apo-hultsch.de oder 034345/22352Bad Lausick Straße der Einheit 10 04651 Bad Lausick Pflegedienst Kühn GmbH Sonntag 8 - 15 Uhr Terminvergabe: Bad Lausick Str. der Einheit 4 www.pflegedienst-kuehn.de 04651 Bad Lausick Ambulanter Pflegedienst ab 15.03.2021 Bennewitz OT "Nicole Reinhold" Mo - Fr 12:30-14:30 Uhr Deuben Nepperwitzer Str. 1 Tagespflege 04828 Deuben Leipziger Str. 90 04828 Deuben Praxis Dr. Rainer Arnold Beucha Dorfstr. 53a 04824 Beucha Gesundheitsamt Brauhausstr. 8 Montag-Freitag Borna 04552 Borna 9-12 Uhr & 13-15 Uhr HNO-Praxis Dr. S. Dreßler, Markt Öffnungszeiten, auch PCR-Tests Tel. 03433 Borna 13, 04552 Borna 205495 Praxis Elias Mauersberger, Am bitte persönliche oder telefonische Anmeldung. Borna Breiten Teich 10, 04552 Borna Apotheke im Kaufland Borna Montag - Samstag, nach Voranmeldung 03433 Borna Am Wilhelmsschacht 34 204 882 04552 Borna Apotheke am Markt vorherige Termin- Brandis Beuchaer Str. 1 vereinbarung 04821 Brandis Ländliches Leben e.V. ab 16.03.2021 Colditz Hauptstr. 38 Dienstag & Donnerstag 04680 Colditz 8-12 Uhr & 15-17 Uhr Mehrzweckhalle "Arche Hausdorf" Hauptstr. 34c 04680 Colditz DRK-Kreisverband Geithain e.V. Mo, Mi, Fr 16-18 Uhr; Di und Do 9 -12 Uhr; Frohburg OT Rodaer Dorfstraße 84 04654 Samstag gerade KW 9 - 12 Uhr Roda Frohburg OT Roda DRK-Kreisverband Geithain e.V. Mo, Mi, Fr 9-12 Uhr; Di und Do 16-18 Uhr; Geithain Bürgerhaus Geithain Louis- Samstag ungerade KW 9-12 Uhr Petermann-Straße 10 04643 Geithain DRK-Kreisverband Muldental Terminvereinbarung 0174/5399163 Grimma e.V. -

Riding the Wave of Success Helsinkihelsinki Oslooslo

Riding the wave of success HelsinkiHelsinki OsloOslo StockholmStockholm h h 15 15 h h h h : : MoscowMoscow 25 25 02 02 10 10 : : : : h h 02 02 5 5 02 02 :0:0 0303 DuDublbinlin 0202 :30:30 h h VancouverVancouver8,3558,355 km km HamburgHamburg LondonLondon 1212: : 1010 h h BerlinBerlin h h WarsawWarsaw 07 07 : 0101 : TorontoToronto6,6356,635 km km :55:55 01 h h BrusselsBrussels 01 8:508:50 h h h h h h 0101 :10 :10 :30:30 :25:25 0101 h h 01 01 ChiChicagocago7,1727,172 km km KievKiev 0202:15:15 h h 1010:00:00 h h ParisParis 0101:35:35 NewNew Y orkYork6,4876,487 km km h h 0909:00:00 h h ViennaVienna 0101:05:05 h h WWashinashingtongton6,8246,824 km km hh :55:55 0909:35:35 h h BeijingBeijing 0909:35:35 h h 0000 7,7317,731 km km ZurichZurich 1010 SanSan F rFanranciscocisco9,4159,415 km km :40:40 h h SeoulSeoul 0101 8,5578,557 km km :55:55 h h :10:10 h h BucharestBucharest 1212 1111:30:30 h h ToTkyookyo LosLos Angeles Angeles9,6259,625 km km 9,3789,378 km km h h 1212:20:20 h h hh :4:04 0 2 2 30 30 0 0 : : 01 01 1111 :10:10 h h HongHong Kong Kong MMadadridrid 0707 9,0599,059 km km RomeRome :30:30 h h DelhiDelhi 10:5010:50 5,9275,927 km km h h BangkokBangkok h h 8:308:30 8,8058,805 km km 03:4003:40 h h h h h h MumbaiMumbai 30 30 : : 1212 11:45 11:45 :05:05 6,3366,336 km km 10 10 h h h h 4040 1919 SingaporeSingapore : : h h :45:45 10,07310,073 km km 1313 3535 h h : : 0505 RioRio de de Janeiro Janeiro 1212 SaoSao Paulo Paulo CapCape eTo Twnown JohannesburgJohannesburg TelTel Aviv Aviv :40:40 DubaiDubai SydneySydney 9,6069,606 km km 9,8689,868 km km 9,1619,161 km km 8,4528,452 km km 2,6442,644 km km h h 4,5704,570 km km 16,16,346346 km km High-tech | 26 Innovation | 18 4 5 Markets | 6 Culture | 22 Nature | 14 Welcome to a place where ambition meets success – where talented people can immerse themselves in a dynamic, fast-growing, inno- vative environment that is teeming with quality of life. -

Beyond the Boat

Beyond the Boat RIVER CRUISE EXTENSION TOURS Welcome! We know the gift of travel is a valuable experience that connects people and places in many special ways. When tourism closed its doors during the difficult months of the COVID-19 outbreak, Germany ranked as the second safest country in the world by the London Deep Knowled- ge Group, furthering its trust as a destination. When you are ready to explore, river cruises continue to be a great way of traveling around Germany and this handy brochure provides tour ideas for those looking to venture beyond the boat or plan a stand-alone dream trip to Bavaria. The special tips inside capture the spirit of Bavaria – traditio- nally different and full of surprises. Safe travel planning! bavaria.by/rivercruise facebook.com/visitbavaria instagram.com/bayern Post your Bavarian experiences at #visitbavaria. Feel free to contact our US-based Bavaria expert Diana Gonzalez: [email protected] TIP: Stay up to date with our trade newsletter. Register at: bavaria.by/newsletter Publisher: Photos: p. 1: istock – bkindler | p. 2: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, Gert Krautbauer | p. 3: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, fotolia – BAYERN TOURISMUS herculaneum79 | p. 4/5: BayTM – Peter von Felbert | p. 6: BayTM – Gert Krautbauer | p. 7: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, Gert Kraut- Marketing GmbH bauer (2), Gregor Lengler, Florian Trykowski (2), Burg Rabenstein | p. 8: BayTM – Gert Krautbauer | p. 9: FC Bayern München, Arabellastr. 17 Burg Rabenstein, fotolia – atira | p. 10: BayTM – Peter von Felbert | p. 11: Käthe Wohlfahrt | p. 12: BayTM – Jan Greune, Gert Kraut- 81925 Munich, Germany bauer | p. -

Freizeit- Und Bildungsprogramm

August 2016 bis Januar 2017 Freizeit- und Bildungsprogramm für Menschen mit und ohne Behinderung und deren Angehörige Fotos v.li.o.: pixelio.de: Bernd von Dahlen, Joujou, www.reisen-sehenswuerdigkeiten.de, Sturm Joujou, Rainer Lanznaster, Dahlen, Maria von Bernd pixelio.de: v.li.o.: Fotos 02 Seite Seite 03 03 Vorwort Monatliches Programm Liebe Leser, liebe Nutzer, 04 Organisatorisches 15 • August 05 Geschäfts-Bedingungen / 23 • September Sie halten unser Freizeit- und Bildungsheft Wie wäre es mit der zweitägigen Fahrt in Zeichenerklärung 31 • Oktober mit weiteren Überraschungen in der Hand. den Bayerischen Wald oder haben Sie Lust 40 • November Wir wollen Sie mit neuen Ideen und kreativen das neue Programm mit zu gestalten? Angebote 47 • Dezember Seiten begeistern. Dann ist die Presse-Werkstatt genau das 06 • Offene Treffs 51 • Januar 2017 Richtige ... Die Angebote in diesem Heft sind vielfältig 08 Erläuterung Gruppe/Werkstatt Mehrtägige Freizeiten und abwechslungsreich. Für ein schönes Viel Spaß beim Blättern und Gestalten 55 Fahrt in den Bayerischen Wald buntes Leben braucht es ein schönes buntes wünscht Ihnen Gruppen Programm! 09 • EM-Fieber 2016 56 Liebe & so Sachen Schöne Veranstaltungen freuen sich auf ihren Das Team der Offenen Hilfen 10 • Eishockey-Spiele Besuch und ihre Teilnahme. Neuburg-Schrobenhausen 11 • JuZe Schrobenhausen Geschäfts-Bedingungen 58 Betreuungskosten / Fahrtkosten Werkstatt 59 Reisen: Kosten / Abmeldung Wir sind auf facebook Freizeit-Sprechstunde 12 • Basteln in Neuburg 60 Kontakt jeden Donnerstag 13 • Presse-Werkstatt -

Student Residences

Contents Things to do before travelling to Germany ........................................... 3 Residence permit: for students who are not from an EU member country 4 Resident registration for all students ................................................... 4 Health insurance ............................................................................... 5 Opening a bank account .................................................................... 6 Accomodation and lifestyle ................................................................. 6 Accomodation – Student residences .................................................... 7 Private student residences ................................................................. 7 Advice/Tips & Tricks .......................................................................... 8 GEZ Licence fee for citizens ................................................................ 8 10 Facts you need to know about living in Germany ............................ 10 Map Deggendorf ............................................................................. 11 Important semester dates ................................................................ 12 Important telephone numbers .......................................................... 12 Contact and advice ......................................................................... 12 Library .......................................................................................... 13 Centre for studies .......................................................................... -

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 07.05.2021

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 07.05.2021 Zu den genannten Einrichtungen bieten auch Ärzte die Tests an Name der Einrichtung Standort / Gebiet Versorgungsform Öffnungszeiten TmH Transport mit Telefonische Terminvereinbarung mobil Sonstiges Herz,Hauptstr. 66 unter 034345 55751 Kerstin 04668 Otterwisch Engelmann DRK Kreisverband Terminvergabe: mobil Sonstiges Muldental e.V. www.drkmuldental.de/schnelltest Standorte Walther-Rathenau-Str. oder 0174 5499100 oder 0174 Nerchau, 1, 04808 Wurzen 5399163 Dürrweitzschen, Mutzschen, Großbardau, Großbothen lola-Aquarium Netto-Markt 9-17 Uhr mobil Sonstiges Ostenstr. 9 Montag: Carsdorfer Str. 8 Pegau Netto-Märkte in 08527 Plauen Dienstag: Schusterstr. 6 Groitzsch Pegau, Mittwoch / Freitag: Groitzsch und Pawlowstr. 2a Borna Borna Donnerstag: Deutzener Str. 7 Borna Löwen Apotheke Termine ww.apo-hultsch.de oder Bad Lausick Apotheke Straße der Einheit 10 034345/22352 04651 Bad Lausick Pflegedienst Kühn Mo - Fr von 13 - 14:30 Uhr, So von Bad Lausick amb. PD GmbH, Str. der Einheit 8 - 15 Uhr Terminvergabe: 4, 04651 Bad Lausick www.pflegedienst-kuehn.de DRK-Kreisverband Kur- und Freizeitbad Riff Bad Lausick Geithain e.V. Am Riff 3, 04651 Bad Lausick Kreisgeschäftsstelle Dresdener Str. 33 b Mo / Mi / Do 9 – 11 Uhr 04643 Geithain Di / Fr 16 – 18 Uhr Häusliche Kranken- Mittwoch 9 - 15 Uhr Bad Lausick Sonstiges und Altenpflege Dorothea Petzold GmbH, Fabianstr. 6 04651 Bad Lausick DRK-Kreisverband Kur- und Freizeitbad Riff Bad Lausick Hilforga- Geithain e.V. Am Riff 3, 04651 Bad Lausick nisation Kreisgeschäftsstelle Mo / Mi / Do 9 – 11 Uhr Dresdener Str. 33 b Di / Fr 16 – 18 Uhr 04643 Geithain DRK WPS im DRK Pflegedienst Bennewitz Bennewitz Sonstiges Muldental GmbH, Leipziger Str. -

Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt a New Lease of Life for the Isar River München

Landeshauptstadt Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt A New Lease of Life for the Isar River München A New Lease of Life for the Isar River presented by: RlfWlfRalf Wulf, Daniela Schaufuß City of Munich, Department of Civil Engineering 11th September 2013 Landeshauptstadt Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt A New Lease of Life for the Isar River München European Watersheds Catchment areas of European Rivers Landeshauptstadt Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt A New Lease of Life for the Isar River München Isar River sections 1 Upper Isar (alpine Character) 2 Isar in Munich (urban character) 3 Middle Isar (alluvial forest) 4 Lower Isar 5 Danube Landeshauptstadt Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt A New Lease of Life for the Isar River München Catchment area 9000 km² Length 270 km Medium Low Discharge 40 m³/s Medium discharge 90 m³/s Medium high discharge 420 m³/s DDiesign fld(flood (100 a) 1.100 m³/s Landeshauptstadt Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt A New Lease of Life for the Isar River München 100 years later Landeshauptstadt Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt A New Lease of Life for the Isar River München Isar in M uni ch ar oun d 1 930 Landeshauptstadt Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt A New Lease of Life for the Isar River München His tor ic Floo ds: collaps of the Ludwigsbridge 13.09.1813 collaps of the Prinzregenten- bridge 1899 Landeshauptstadt Isar-Plan Munich München Wasserwirtschaftsamt A New Lease of Life for the Isar River München Flauchersteg Landeshauptstadt -

The State Reservoir Administration of Saxony Property from Floods

Masthead Publisher: Landestalsperrenverwaltung des Freistaates Sachsen Bahnhofstraße 14, 01796 Pirna, Germany Internet: www.talsperren-sachsen.de Tel.: +49 (0) 3501 796 – 0, Fax: +49 (0) 3501 796-116 E-mail: [email protected] Editors: Press and Public Relations Copy Deadline: February 2007 Photographs: Landestalsperrenverwaltung des Freistaates Sachsen, Kirsten J. Lassig, www.photocase.com Circulation: 1,000 copies Design: Heimrich & Hannot GmbH Printing: Druckfabrik Dresden GmbH Paper: 100 % chlorine free bleached THE STATE RESERVOIR (No access for electronically signed as well as for encrypted electronic documents) ADMINIstrATION OF SAXONY Note This informational brochure is published by the Saxon State Government in the scope of its public relations work. It may not be used by parties or campaign Function – Organization – Projects aids for the purpose of election advertising. This is valid for all elections. CONTENts 4 10 12 14 18 24 FOREWORD ORGANIZATION OF THE THE NERVE CENTER ON-SITE EXPERTISE: Zwickauer Mulde/ FLOOD PROTECTION AND STATE RESERVOIR OF THE STATE RESERVOIR THE REGIONAL WORKS Obere Weiße Elster DRINKING WATER SUPPLy – 5 ADMINISTRATION OF SAXONY ADMINISTRATION OF SAXONY: TWO EXAMPLES STEWARDSHIP HEADQUARTERS IN PIRNA 14 20 OF SAXony’S WATERS Oberes Elbtal Spree/Neiße 24 Function of the State Reservoir Comprehensive flood protection Administration of Saxony 16 22 for the city of Torgau Freiberger Mulde/ Elbaue/Mulde/ Zschopau Untere Weiße Elster 26 Complex overhaul of the Klingenberg dam 2 CONTENTS 3 FOREWORD The first water reservoirs in Saxony were built as Saxony was founded in 1992 as the first public early as 500 years ago. The mining industry was enterprise in Saxony. -

Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany

Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany This book is about the ethics of nursing and midwifery, and how these were abrogated during the Nazi era. Nurses and midwives actively killed their patients, many of whom were disabled children and infants and patients with mental (and other) illnesses or intellectual disabilities. The book gives the facts as well as theoretical perspectives as a lens through which these crimes can be viewed. It also provides a way to teach this history to nursing and midwifery students, and, for the first time, explains the role of one of the world’s most historically prominent midwifery leaders in the Nazi crimes. Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Susan Benedict is Professor of Nursing, Director of Global Health, and Co- Director of the Campus-Wide Ethics Program at the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Nursing in Houston. Linda Shields is Professor of Nursing—Tropical Health at James Cook Uni- versity, Townsville, Queensland, and Honorary Professor, School of Medi- cine, The University of Queensland. Routledge Studies in Modern European History 1 Facing Fascism 9 The Russian Revolution of 1905 The Conservative Party and the Centenary Perspectives European dictators 1935–1940 Edited by Anthony Heywood and Nick Crowson Jonathan D. Smele 2 French Foreign and Defence 10 Weimar Cities Policy, 1918–1940 The Challenge of Urban The Decline and Fall of a Great Modernity in Germany Power John Bingham Edited by Robert Boyce 11 The Nazi Party and the German 3 Britain and the Problem of Foreign Office International Disarmament Hans-Adolf Jacobsen and Arthur 1919–1934 L. -

Demographisches Profil Für Den Landkreis Ostallgäu

Beiträge zur Statistik Bayerns, Heft 553 Regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Bayern bis 2039 x Demographisches Profil für den xLandkreis Ostallgäu Hrsg. im Dezember 2020 Bestellnr. A182AB 202000 www.statistik.bayern.de/demographie Zeichenerklärung Auf- und Abrunden 0 mehr als nichts, aber weniger als die Hälfte der kleins- Im Allgemeinen ist ohne Rücksicht auf die Endsummen ten in der Tabelle nachgewiesenen Einheit auf- bzw. abgerundet worden. Deshalb können sich bei der Sum mierung von Einzelangaben geringfügige Ab- – nichts vorhanden oder keine Veränderung weichun gen zu den ausgewiesenen Endsummen ergeben. / keine Angaben, da Zahlen nicht sicher genug Bei der Aufglie derung der Gesamtheit in Prozent kann die Summe der Einzel werte wegen Rundens vom Wert 100 % · Zahlenwert unbekannt, geheimzuhalten oder nicht abweichen. Eine Abstimmung auf 100 % erfolgt im Allge- rechenbar meinen nicht. ... Angabe fällt später an X Tabellenfach gesperrt, da Aussage nicht sinnvoll ( ) Nachweis unter dem Vorbehalt, dass der Zahlenwert erhebliche Fehler aufweisen kann p vorläufiges Ergebnis r berichtigtes Ergebnis s geschätztes Ergebnis D Durchschnitt ‡ entspricht Publikationsservice Das Bayerische Landesamt für Statistik veröffentlicht jährlich über 400 Publikationen. Das aktuelle Veröffentlichungsverzeich- nis ist im Internet als Datei verfügbar, kann aber auch als Druckversion kostenlos zugesandt werden. Kostenlos Publikationsservice ist der Download der meisten Veröffentlichungen, z.B. von Alle Veröffentlichungen sind im Internet Statistischen -

Influential Parameters of Surface Waters on the Formation of Coating Onto Tio2 Nanoparticles Under Natural Conditions

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Environmental Science: Nano. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2021 Influential parameters of surface waters on the formation of coating onto TiO2 nanoparticles under natural conditions Narjes Tayyebi Sabet Khomami a, Parthvi Mayurbhai Patel a, Cynthia Precious Jusi a, Vanessa Trouillet b, Jan Davida, Gabrielle. E. Schaumanna, Allan Philippe a* * Corresponding author a iES Landau, Institute for Environmental Sciences, Koblenz-Landau University, Fortstrasse 7, 76829 Landau, Germany. b Institute for Applied Materials (IAM) and Karlsruhe Nano Micro Facility (KNMF), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), 76344 Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany. 1 Table S1: The locations of surface water (SW) sites and their descriptions. Abbr. Site GPS Location Type of Description landscape SW1 Rehbach 49° 21′ 20″ N urban Is tributary of the Speyerbach river which flows through the Winziger 8° 9′ 19″ E Wassergescheid in Neustadt Weinstrasse. SW2 Speyerbach 49°19'04.8"N urban The Speyerbach is a left tributary of the Rhine river and flows through the 8°26'49.5"E southern palatinate forest as splits into smaller water courses before emptying out into the Rhine. SW3 Bischofsweiher 49°20'40.4"N forest Bischofsweier is an artificial lake dammed from inflows from the 8°05'18.2"E Kaltenbrunnertalbach stream and serves as a recreational fishing lake. SW4 Kaltenbrunnertal 49°20'40.4"N forest Kaltenbrunnertalbach is a stream that flows from the northern summit of -bach 8°05'18.2"E Hüttenhohl and maintains its course through the southern palatinate forest before emptying into Rehbach. SW5 Modenbach 49°16'12.4"N agricultural Modenbach is a stream, just under 30 kilometers long, and a right-hand tributary 8°10'58.4'' E of the Speyerbach. -

Land Use Effects and Climate Impacts on Evapotranspiration and Catchment Water Balance

Institut für Hydrologie und Meteorologie, Professur für Meteorologie climate impact Q ∆ ∆ E ● p basin impact ∆Qobs − ∆Qclim P ● ● ● P ● ● ● ●● ●● ● ●● ● −0.16 ●●● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●●●●●● ●●●●● ● ●●● ●● ● ●● ●● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●●● U −0.08 ● ● ●● ●● ●●● ● ● ●● ● ●● ● ● ●● ●● ● ● ●● ∆ ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●● ● ● ●●● ●● ● ● ●●●●●● ● ●●●● ●● ●●●● ●●● ● ●●●● ● ● 0 ● ●● ● ●●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●● ● ● ●●●●●● ● ●● ● ● ● ●● ● ● ●● ● ●● ● ● ●● ●● ● ●● ●● ●●● ●●● ● ● ● ●● ●● ● ● ●● 0.08 ● ● ●●● ●●● ●●● ● ●● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●●●●●●● ●● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 0.16 ● ● ●● ●● ● ●●● ● ●● ● ●● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ● climate impact ● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ● Q ● ● ● ●● ● ● ● ● ● − ∆ ● ● ● ● ● ●● − ∆ ● ● ● E ● ● p basin impact ● P −0.2 −0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 −0.2 −0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 ∆W Maik Renner● Land use effects and climate impacts on evapotranspiration and catchment water balance Tharandter Klimaprotokolle - Band 18: Renner (2013) Herausgeber Institut für Hydrologie und Meteorologie Professur für Meteorologie Tharandter Klimaprotokolle http://tu-dresden.de/meteorologie Band 18 THARANDTER KLIMAPROTOKOLLE Band 18 Maik Renner Land use effects and climate impacts on evapotranspiration and catchment water balance Tharandt, Januar 2013 ISSN 1436-5235 Tharandter Klimaprotokolle ISBN 978-3-86780-368-7 Eigenverlag der Technischen Universität Dresden, Dresden Vervielfältigung: reprogress GmbH, Dresden Druck/Umschlag: reprogress GmbH, Dresden Layout/Umschlag: Valeri Goldberg Herausgeber: Christian Bernhofer und Valeri Goldberg Redaktion: Valeri Goldberg Institut für