The Growing Number of Given Names As a Clue to the Beginning of the Demographic Transition in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C21 Ambiti Paesaggio Ptrc

COMUNE DI TRIBANO Provincia di Padova P.A.T. Elaborato Scala 1:10.000 Ambiti di paesaggio - estratto PTRC Allegato al Documento Preliminare COMUNE diTribano VANZO PAT CONSELVE SAN COSMA Ufficio di Piano Responsabile Geom. David Trivellato TRIBANO Gruppo di lavoro multidisciplinare Pianificazione urbanistica - quadro conoscitivo - coordinamento - POZZONOVO OLMO DI TRIBANO Arch. Giancarlo Ghinello OLMO DI BAGNOLI Studio Giotto Associato BAGNOLETTO Sistema ambientale - sistema BAGNOLI DI SOPRA agricolo - paesaggio rurale Dr. Agr. Giacomo Gazzin Studio Agriplan Sistema ambientale fisico - difesa del suolo - compatibilità geologica Dr. Geol. Alberto Stella Georicerche s.r.l. Compatibilità idraulica Ing. Giuliano Zen Relazione ambientale - vas Dr. Antonio Buggin Giugno 2012 PTRC Ambiti di paesaggio 392 0.0 2.5 5.0 7.5 10.0 12.5 Km Superfi cie dell’ambito: 32 BASSA PIANURA 664.36 Km2 TRA IL BRENTA E L’ADIGE Incidenza sul territorio regionale: 3.61% insediamenti produttivi fasce alberate campi di forma allungata sistema dei corsi d’acqua edifi cazione diffusa Insediamenti diffusi in pianura e taglio Brenta (Unipd) PTRC Ambiti di paesaggio 1. IDENTIFICAZIONE GENERALE FISIOGRAFIA Ambito di bassa pianura. L’ambito è posto tra l’area della Riviera del Brenta a nord e l’area delle bonifi che del Polesine a sud; è delimitato ad est dall’area lagunare di gronda ed a ovest dalla Strada Statale 16 Adriatica. INQUADRAMENTO NORMATIVO La parte dell’ambito situata ad est verso la laguna è disciplinata dal Piano di Area della Laguna e dell’Area Veneziana (PALAV), approvato dalla Regione Veneto nel novembre 1995, in attuazione dell’area di tutela paesaggistica di interesse regionale individuata dal PTRC 1991. -

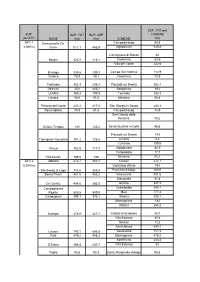

POSTI PER Contratti a Tempo Determinato

Profilo Collaboratore scolastico: Posti disponibili per CONTRATTI A TEMPO DETERMINATO a.s. 2020/21 posti part- posti al posti al Scuola Comune time Ore Note 31/8/2021 30/6/2021 30/6/2021 IC DI ABANO TERME ABANO TERME 1 18 ore IIS ALBERTI ABANO TERME 1 30 ore IPSAR P.D'ABANO ABANO TERME 1 24 ore CTP ALBIGNASEGO ALBIGNASEGO 1 12 ore 18 ore IC DI ALBIGNASEGO ALBIGNASEGO 7 2 12 ore IC E. DE AMICIS BORGO VENETO 1 30 ore IC DI BORGORICCO BORGORICCO 1 1 12 ore IC DI CADONEGHE CADONEGHE 1 1 18 ore IC DI CAMPODARSEGO CAMPODARSEGO 1 1 24 ore I.C. DI CAMPOSAMPIERO "PARINI" CAMPOSAMPIERO 1 1 18 ore IIS I.NEWTON-PERTINI CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPOSAMPIERO 2 1 18 ore IC CARMIGNANO-FONTANIVA CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA 6 1 30 ore 18 ore IC CASALE DI SCODOSIA CASALE DI SCODOSIA 2 12 ore IC DI CASALSERUGO CASALSERUGO 1 DI CERVARESE SANTA CROCE CERVARESE SANTA CROCE 1 1 1 18 ore CTP CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 1 I.I.S. "A MEUCCI" - CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 1 30 ore IC DI CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 9 1 IIS T.LUCREZIO CARO-CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 1 1 18 ore posti part- posti al posti al Scuola Comune time Ore Note 31/8/2021 30/6/2021 30/6/2021 ITE GIRARDI -CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 1 12 ore IC DI CODEVIGO CODEVIGO 2 2 1 18 ore IC DI CONSELVE CONSELVE 1 1 18 ore IC DI CORREZZOLA CORREZZOLA 3 1 24 ore IC DI CURTAROLO CURTAROLO 1 24 ore IC CARRARESE EUGANEO DUE CARRARE 1 1 30 ore IC PASCOLI ESTE 1 1 1 21 ore IIS "ATESTINO" ESTE 1 1 18 ore IIS "EUGANEO" ESTE 1 1 IIS "FERRARI" ESTE 1 2 12 ore; 12 ore; IC DI GALLIERA VENETA GALLIERA VENETA 1 1 1 24 ore 13 ore; 18 ore; IC GRANTORTO E S. -

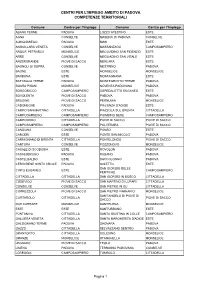

Centri Per L'impiego Ambito Di Padova Competenze Territoriali

CENTRI PER L'IMPIEGO AMBITO DI PADOVA COMPETENZE TERRITORIALI Comune Centro per l’Impiego Comune Centro per l’Impiego ABANO TERME PADOVA LOZZO ATESTINO ESTE AGNA CONSELVE MASERA' DI PADOVA CONSELVE ALBIGNASEGO PADOVA MASI ESTE ANGUILLARA VENETA CONSELVE MASSANZAGO CAMPOSAMPIERO ARQUA' PETRARCA MONSELICE MEGLIADINO SAN FIDENZIO ESTE ARRE CONSELVE MEGLIADINO SAN VITALE ESTE ARZERGRANDE PIOVE DI SACCO MERLARA ESTE BAGNOLI DI SOPRA CONSELVE MESTRINO PADOVA BAONE ESTE MONSELICE MONSELICE BARBONA ESTE MONTAGNANA ESTE BATTAGLIA TERME PADOVA MONTEGROTTO TERME PADOVA BOARA PISANI MONSELICE NOVENTA PADOVANA PADOVA BORGORICCO CAMPOSAMPIERO OSPEDALETTO EUGANEO ESTE BOVOLENTA PIOVE DI SACCO PADOVA PADOVA BRUGINE PIOVE DI SACCO PERNUMIA MONSELICE CADONEGHE PADOVA PIACENZA D'ADIGE ESTE CAMPO SAN MARTINO CITTADELLA PIAZZOLA SUL BRENTA CITTADELLA CAMPODARSEGO CAMPOSAMPIERO PIOMBINO DESE CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPODORO CITTADELLA PIOVE DI SACCO PIOVE DI SACCO CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPOSAMPIERO POLVERARA PIOVE DI SACCO CANDIANA CONSELVE PONSO ESTE CARCERI ESTE PONTE SAN NICOLO' PADOVA CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA CITTADELLA PONTELONGO PIOVE DI SACCO CARTURA CONSELVE POZZONOVO MONSELICE CASALE DI SCODOSIA ESTE ROVOLON PADOVA CASALSERUGO PADOVA RUBANO PADOVA CASTELBALDO ESTE SACCOLONGO PADOVA CERVARESE SANTA CROCE PADOVA SALETTO ESTE SAN GIORGIO DELLE CINTO EUGANEO ESTE CAMPOSAMPIERO PERTICHE CITTADELLA CITTADELLA SAN GIORGIO IN BOSCO CITTADELLA CODEVIGO PIOVE DI SACCO SAN MARTINO DI LUPARI CITTADELLA CONSELVE CONSELVE SAN PIETRO IN GU CITTADELLA CORREZZOLA PIOVE DI SACCO SAN PIETRO -

Mortality Selection in the First Three Months of Life and Survival in the Following Thirty-Three Months in Rural Veneto (North-East Italy) from 1816 to 1835

Mortality selection in the first three months of life and survival in the following thirty-three months in rural Veneto (North-East Italy) from 1816 to 1835 Leonardo Piccione, University of Padova, Italy Gianpiero Dalla-Zuanna, University of Padova, Italy Alessandra Minello, European University Institute, Italy Abstract BACKGROUND A number of studies have examined the influence of life conditions in infancy (and pregnancy) on mortality risks in adulthood or old age. For those individuals who survived difficult life conditions, some scholars have found a prevalence of positive selection (relatively low mortality within the population), while others have observed the prevalence of a so-called scar-effect (relatively high mortality within the population). OBJECTIVE Using micro-data characterized by broad internal mortality differences before the demographic transition (forty-three parishes within the region of Veneto, North-East Italy, 1816-35), we aim to understand whether children who survived high mortality risks during the first three months of life (early infant mortality) had a higher or a lower probability of surviving during the following 33 months (late infant mortality). METHODS Using a Cox regression, we model the risk of dying during the period of 3-35 months of age, considering mortality level survived at age 0-2 months of age as the main explanatory variable. 1 RESULTS We show that positive selection prevailed. For cohorts who survived very severe early mortality selection (q0-2 > 400‰, where the subscripts are months of age), the risk of dying was 20-30% lower compared to the cohorts where early mortality selection was relatively small (q0-2 < 200‰). -

Padova-Piove Di Sacco-Correzzola-Cantarana

Linea - E002 - PADOVA-PIOVE DI SACCO-CORREZZOLA-CANTARANA Vettore Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Cadenza fer fer fer fsc fVsc Sfns fsc fVsc Ssc fVsc fVns fVsc Sfns Note PP YH PADOVA AUTOSTAZIONE 10.45 . 12.25 12.40 13.15 13.15 . 14.10 14.10 17.45 17.45 18.30 18.30 PADOVA P.BOSCHETTI 10.48 . 12.28 12.43 13.18 13.18 . 14.13 14.13 17.48 17.48 18.33 18.33 PADOVA OSPEDALE 10.50 . 12.30 12.45 13.20 13.20 . 14.16 14.15 17.51 17.50 18.36 18.35 PADOVA PONTECORVO V.FACCIOLATI 10.53 . 12.33 12.48 13.23 13.23 . 14.20 14.18 17.55 17.53 18.40 18.38 PADOVA VOLTABAROZZO 11.00 . 12.40 12.55 13.30 13.30 . 14.28 14.25 18.06 18.00 18.51 18.45 RONCAGLIA 11.03 . 12.43 12.58 13.33 13.33 . 14.31 14.28 18.10 18.03 18.55 18.48 P.TE SAN NICOLO' 11.07 . 12.47 13.02 13.37 13.37 . 14.35 14.32 18.14 18.07 18.59 18.52 LEGNARO 11.11 . 12.51 13.06 13.41 13.41 . 14.39 14.36 18.18 18.11 19.03 18.56 VIGOROVEA 11.17 . 12.57 13.12 13.47 13.47 . 14.45 14.42 18.24 18.17 19.09 19.02 BV. BRUGINE 11.18 . -

Ing. Andrea Martini

ing. Indirizzo corrente: Andrea Martini Via Cavalieri di Vittorio Veneto, 11 I ‐ 35020 Pernumia (PD) Tel.: +39 (0) 429 779149 Fax: +39 (0) 429 763329 Mob.: +39 334 8451987 e‐mail: [email protected] Luogo e data di nascita: Monselice, 15/04/1976 Esperienze lavorative Martini Andrea Studio di Ingegneria Pernumia (PD) MAR. 2007 Progettazione di edifici ad elevata efficienza energetica e OGGI di impianti ad energie rinnovabili. Sicurezza O.C.S. SpA Divisione Architettura LUG. 2005 Albignasego (PD) MAR. 2007 Serramenti, Facciate continue. Uff. tecnico e cantiere. MANOLI srl SETT. 2004 Torreglia (PD) Manutenzione impianti di distribuzione carburanti. GIU. 2005 Uff. tecnico e cantiere. CM Brunello snc GEN. 2003 Pernumia (PD) AGO. 2004 Serramenti, Facciate continue. Uff. tecnico e cantiere. MARTINI snc Pernumia (PD) Progettazione e realizzazione di macchine speciali per l’industria meccanica. Collaboratore. Referenze professionali ATTIVITA’ IN AMBITO PROTEZIONE CIVILE Incarico per la redazione dei Piani Comunali di Protezione Civile 2012 ‐ Oggi dei Comuni di Abano Terme, Montegrotto Terme, Due Carrare. Redazione del Piano Comunale di Protezione Civile per il Comune 2007 di Pernumia (PD). ATTIVITA’ IN AMBITO PROGETTAZIONE INTEGRATA Progettazione edile ed impiantistica, coordinamento della 2014 sicurezza per l’ampliamento di un edificio ad uso produttivo. Progettazione edile ed impiantistica, coordinamento della 2013 sicurezza per l’ampliamento di un edificio ad uso residenziale. Progettazione edile ed impiantistica, coordinamento della 2013 sicurezza per la ristrutturazione di un edificio ad uso residenziale bifamiliare. Progettazione per l’efficientamento energetico, smaltimento 2013 amianto ed installazione impianto fotovoltaico da 104,75 kWp su edificio produttivo sito a Camponogara (VE). ATTIVITA’ IN AMBITO COORDINAMENTO SICUREZZA 2011 ‐ 2014 Progetti per la sicurezza in occasione della convocazione delle 1 Commissioni Comunali di Vigilanza sui Locali di Pubblico Spettacolo ‐ Comuni di Piove di Sacco, Campodoro, Santa Margherita d’Adige. -

SUP. SUP. TOT Per COMUNE Per

SUP. TOT per SUP. SUP. TOT SUP. ASP COMUNE per ATC NOME (ha) (ha) COMUNE (ha) ATC 1Barrucchella Ca' Campodarsego 84,3 3.086 haFarini 611,1 456,9 Vigodarzere 526,8 Carmignano di Brenta 42 Boschi 125,9 115,1 Fontaniva 83,9 Villa del Conte 222,6 Busiago 335,5 299,3 Campo San Martino 112,9 Colonia 72,9 40,1 Fontaniva 72,9 Contarina 352,4 236,4 Piazzola sul Brenta 352,4 Desman 503 405,7 Borgoricco 503 La Mira 160,3 109,8 Tombolo 160,3 Lissaro 55,8 51,8 Mestrino 55,8 Palazzo del Conte 243,3 217,8 San Giorgio in Bosco 243,3 Reschigliano 74,5 61,8 Campodarsego 74,5 San Giorgio delle Pertiche 89,2 Guizze-Tergola 148 125,4 Santa Giustina in Colle 58,8 Piazzola sul Brenta 143 Tremignon Vaccarino 151,2 125,5 Limena 8,2 Curtarolo 109,6 Vanzo 142,5 117,3 Vigodarzere 32,9 Campodoro 17,7 Villa Kerian 109,8 106 Mestrino 92,1 ATC 2 Abbazia 272,7 252,1 Carceri 272,7 6.204 ha Vighizzolo d'Este 154 Barchessa al Lago 314,6 303,5 Piacenza d'Adige 160,6 Boara Pisani 481,6 463,2 Vescovana 481,6 Stanghella 57,4 Ca' Conti/2 404,6 383,5 Granze 347,2 Campagnazza Castelbaldo 348,1 Pajette 525,5 509,9 Masi 177,4 Campagnon 399,1 376,1 Urbana 399,1 Montagnana 182 Urbana 268,2 Grompe 478,9 427,1 Casale di Scodosia 28,7 Villa Estense 31,6 Granze 14,2 Sant'Urbano 540,1 Lavacci 743,1 696,8 Vescovana 157,2 Palù 475,2 448,3 Montagnana 475,2 Sant'Elena 233,4 S.Elena 298,4 287,7 Villa Estense 65 Taglie 95,8 93,3 Santa Margherita d'Adige 95,8 Tre Canne 218,4 216,8 Vighizzolo d'Este 218,4 Val Vecchia - Val Casale di Scodosia 348,8 Nuova 673 662,3 Merlara 324,2 Valli 202,8 197,3 -

Il Tesoretto Dimenticato in Banca Oltre 1400 Conti Correnti E Libretti Di Deposito «Dormienti» Di Claudio Malfitano Più Di 1.400 Conti Dormienti Nel Padovano

MC6POM...............06.12.2008.............20:31:09...............FOTOC24 il mattino DOMENICA 7 dicembre 2008 25 PADOVAECONOMIA Il ministro dell’Economia Giulio Tremonti ha annuciato che il Tesoro incasserà le somme in giacenza negli istituti di credito Il tesoretto dimenticato in banca Oltre 1400 conti correnti e libretti di deposito «dormienti» di Claudio Malfitano Più di 1.400 conti dormienti nel Padovano. In pratica al- meno 1 milione e 200 mila eu- La benzina ro «dimenticati» tra depositi Quasi 800 milioni e libretti, in banca come in po- sta, che non registrano movi- incassati dallo Stato prezzi bassi menti da almeno 10 anni. E Il caso del signor che verranno «incamerati» I prezzi dei carburanti dallo Stato tra dieci giorni, Eugenio Antico continuano a scendere sul- quando scade il termine per la scia del crollo delle quo- «risvegliare» il proprio conto di Pontelongo e di tazioni internazionali del dimenticato rivolgendosi alle petrolio. E per il primo banche. Per chi non lo farà ci Jessica Bellotto ponte invernale sulla na- sarà un’altra possibilità, ma ve è una notizia positiva: bisogna rivolgersi al ministe- un risparmio rispetto alle ro dell'Economia. I soldi po- Feste 2007 di oltre 11 euro tranno essere recuperati per per ogni rifornimento com- altri 10 anni. pleto di un'auto di media UN MILIONE DI EURO. cilindrata se la vettura è a Alcuni proprietari risultano benzina, oltre 8,5 euro in nati più di cento anni fa: po- meno se è diesel. Per chi trebbero essere morti senza ha deciso di trascorrere eredi. Oppure gli eredi ignora- questo primo ponte del- no l'esistenza del conto. -

Formato Europeo P E R I L CURRICULUM VITAE

Formato europeo P E R I L CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome POLATO CARLO Indirizzo VIA VITTORIO 33/A 35040 PONSO PD Telefono 0429/656108 Fax 0429/95014 E-mail edilizia [email protected] Nazionalità Italiana Data di nascita 24/06/1951 DATORE DI LAVORO Unione dei Comuni della Megliadina dal 1° gennaio 2014 con la Qualifica di Responsabile area VII° Edilizia Privata e Patrimonio dell’UNione COMUNE DI PONSO A FAR DATA 1 SETTEMBRE 2008 Cat. D1 Responsabile del Servizio LL.PP Urbanistica Edilizia Privata e Patrimonio. ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA NELL’AMBITO DELL’URBANISTICA COMMITTENTE COMUNE DI BARBONA HO REDATTO COME PROGETTISTA UNA VARIANTE PARZIALE AL P.R.G. ANNO 2006 AI SENSI DELL’ART 48, COMMA 1 TER , DELLA L.R. 23 APRILE 2004 N. 11, COME MODIFICATA DALLA L.R. 2 DICEMBRE 2005 N. 23; ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA NELL’AMBITO DEI LAVORI PUBBLICI OPERA REALIZZATA NEL 2012 1) LAVORI AMPLIAMENTO CIMITERO DI BRESEGA PROGETTAZIONE E DIREZIONE LAVORI OPERA REALIZZATA NEL 2008 2) AMPLIAMENTO ILLUMINAZIONE PUBBLICA PONSO PROGETTAZIONE E DIREZIONE COMMITTENTE COMUNE DI PONSO LAVORI COMMITTENTE COMUNE DI 3) REALIZZAZIONE DI NUOVO BLOCCO CIMITERIALE A POZZONOVO FRAZIONE STROPPARE POZZONOVO PD OPERA REALIZZATA NEL 2006 COMMITTENTE CONSORZIO 4) PROGETTAZIONE DEI LAVORI DI ADEGUAMENTO DEL PLESSO SCOLASTICO AL FINE DI METROPOLIS ACCORPARE LE SCUOLE ELEMENTARI E MEDIE PER IL COMUNE DI POZZONOVO OPERA REALIZZATA NEL 2005 /2007 COMMITTENTE COMUNE DI SAN 5) INTERVENTI DI MANUTENZIONE E SISTEMAZIONE DEI CORPI STRADALI, IN PIETRO VIMINARIO PARTICOLARE VIA CRISTO 2° STRADA, VIA VALDOLMO 1° E 2° STRADA, VIA DEI OPERA REALIZZATA NEL 2005 /2006 RUBINI, VIA BARANE E PUNTI CRITICI. -

Este Baone Arquà Petrarca Monselice Pernumia Battaglia Terme Galzignano Terme Montegrotto Terme Abano Terme Teolo Treponti Torr

Bike l Pedalando s'impara Ciclovia L l Anello Colli Euganei 1 3 18 Ciclovia G Itinerario e beni culturali 27 28 41 54 Questo percorso ciclabile circonda interamente il Parco Regionale dei Colli Euganei, offrendo la 59 possibilità a quanti lo percorrono di immergersi in uno splendido paesaggio fatto di verdi colline 15 di origine vulcanica, limpidi corsi d’acqua e incantevoli borghi storici. 149 34 2 31 35 I siti d’interesse culturale lungo il tracciato ciclabile punteggiano il territorio in un susseguirsi 189 25 47 49 Selvazzano ravvicinato di ville venete, chiese, aree archeologiche, musei, palazzi storici, castelli e torri me- Dentro dievali. Visitarli tutti in un’unica giornata in sella alla bici è naturalmente impossibile: si consiglia 16 153 Treponti 19 85 116 di pianificare il proprio itinerario di viaggio in anticipo e di scegliere accuratamente i siti che si 121 143 17 20 intendono visitare. 18 65 177 Da questa incredibile concentrazione di evidenze culturali appare chiaro come i Colli rappresenti- 87 94 Abano Terme no da sempre un luogo di forte richiamo per quanti sono in cerca di quiete e intendono godersi il 154 21 74 relax lontano dalle affollate e caotiche città della pianura circostante: ad Arquà si ritirò Petrarca 123 151 92 per assaporare la pace dei Colli e il fascino antico del borgo, durante i suoi ultimi anni di vita; a Teolo 89 99 100 122 52 93 Montegrotto, già in epoca romana, si giungeva per rilassarsi (e per curarsi) immersi nelle calde 14 95 22 135 159 Montegrotto acque termali; ovunque i nobili padovani e veneziani hanno edificato, nel corso del Cinque-Sei e Torreglia Terme Settecento, le proprie lussuose residenze d’ozio. -

Discover Padua and Its Surroundings

2647_05_C415_PADOVA_GB 17-05-2006 10:36 Pagina A Realized with the contribution of www.turismopadova.it PADOVA (PADUA) Cittadella Stazione FS / Railway Station Porta Bassanese Tel. +39 049 8752077 - Fax +39 049 8755008 Tel. +39 049 9404485 - Fax +39 049 5972754 Galleria Pedrocchi Este Tel. +39 049 8767927 - Fax +39 049 8363316 Via G. Negri, 9 Piazza del Santo Tel. +39 0429 600462 - Fax +39 0429 611105 Tel. +39 049 8753087 (April-October) Monselice Via del Santuario, 2 Abano Terme Tel. +39 0429 783026 - Fax +39 0429 783026 Via P. d'Abano, 18 Tel. +39 049 8669055 - Fax +39 049 8669053 Montagnana Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 Castel S. Zeno Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 Tel. +39 0429 81320 - Fax +39 0429 81320 (sundays opening only during high season) Teolo Montegrotto Terme c/o Palazzetto dei Vicari Viale Stazione, 60 Tel. +39 049 9925680 - Fax +39 049 9900264 Tel. +39 049 8928311 - Fax +39 049 795276 Seasonal opening Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 nd TREVISO 2 Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 AIRPORT (sundays opening only during high season) MOTORWAY EXITS Battaglia Terme TOWNS Via Maggiore, 2 EUGANEAN HILLS Tel. +39 049 526909 - Fax +39 049 9101328 VENEZIA Seasonal opening AIRPORT DIRECTION TRIESTE MOTORWAY A4 Travelling to Padua: DIRECTION MILANO VERONA MOTORWAY A4 AIRPORT By Air: Venice, Marco Polo Airport (approx. 60 km. away) By Rail: Padua Train Station By Road: Motorway A13 Padua-Bologna: exit Padua Sud-Terme Euganee. Motorway A4 Venice-Milano: exit Padua Ovest, Padua Est MOTORWAY A13 DIRECTION BOLOGNA adova. -

Relazione Agronomica

COMUNE DI TERRASSA PADOVANA P.A.T. Provincia di Padova Elaborato B 2 10 Scala Relazione agronomica Sindaco Betto Ezio Responsabile Ufficio Tecnico Momolo geom. Massimo Studio Agronomico dott. Agr. Giuliano Bertoni Marzo 2013 PROVINCIA DI PADOVA COMUNE DI TERRASSA PADOVA PIANO DI ASSETTO DEL TERRITORIO RELAZIONE AGRONOMICA Pagina 1 di 29 INDICE 1) L’economia diffusa e policentrica del Veneto Pag. 3 2) Evoluzione storica dei sistemi agricoli Pag. 5 3) Analisi sintetica di alcuni indicatori socio-economici Pag. 8 4) Analisi del territorio comunale: Pag. 16 a) Copertura del suolo comunale (STC) Pag. 16 5) Attività agricola nel territorio rurale Pag. 18 a) Copertura del suolo agricolo Pag. 18 b) Classificazione agronomica dei suoli Pag. 20 c) Aree agro-ambientalmente fragili Pag. 22 d) Elementi produttivi strutturali Pag. 23 e) Aree soggette a frequenti e persistenti allagamenti Pag. 24 f) Rete idraulica minore e manufatti Pag. 25 4) Invarianti di natura agricolo – produttiva Pag. 26 5) Superficie Agricola Utilizzata (SAU) Pag. 27 7) Calcolo della SAU Trasformabile Pag. 29 Pagina 2 di 29 L’ECONOMIA DIFFUSA E POLICENTRICA DEL VENETO Il Veneto, importante regione italiana per la consistenza di molte produzioni agricole, costituisce un laboratorio interessante per comprendere quali siano stati i risultati, in termini di “sistema agricolo”, dell'azione di molteplici variabili endogene ed esogene al sistema stesso. Più in particolare sembra opportuno sottolineare che il ‘sistema agricolo Veneto’ è stato identificato come ‘nuovo’ non perché contrapposto al sistema agricolo Veneto del passato ma, piuttosto, perché pur avendo come base di partenza i valori e le potenzialità produttive ed organizzative della tradizione agricola della regione e pur avvalendosi della loro persistenza, ha sviluppato caratteri peculiari propri.