Paper We Use the Following Definitions: Neonatal Mortality (First Month), Early Mortality (First Three Months), and Infant Mortality (First Year)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stato Delle Acque Sotterranee Della Provincia Di Padova

STATO DELLE ACQUE SOTTERRANEE DELLA PROVINCIA DI PADOVA Anno 2017 ARPAV Commissario Straordinario Riccardo Guolo Direttore Tecnico Carlo Terrabujo Dipartimento Provinciale di Padova Alessandro Benassi Progetto e realizzazione: Servizio Monitoraggio e Valutazioni Claudio Gabrieli Redazione: Glenda Greca Gruppo di lavoro: Paola Baldan, Cinthia Lanzoni, Roberta Millini, Silvia Rebeschini, Daniele Suman Analisi di laboratorio: Dipartimento Regionale Laboratori Supporto e collaborazione del Servizio Acque Interne È consentita la riproduzione di testi, tabelle, grafici ed in genere del contenuto del presente rapporto esclusivamente con la citazione della fonte. 2 INDICE 1. Presentazione ............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Quadro normativo ....................................................................................................................... 4 3. Quadro territoriale di riferimento .................................................................................................. 5 3.1 Inquadramento idrogeologico ................................................................................................ 5 4. Le pressioni sul territorio ............................................................................................................. 9 5. La rete di monitoraggio delle acque sotterranee........................................................................ 11 5.1 Parametri e frequenze: monitoraggio qualitativo ................................................................. -

Euganean Hills the Euganean Hills Are Located in the Veneto Region

Euganean Hills The Euganean Hills are located in the Veneto region. They are often referred to as “sea cliffs” that stand proudly at the heart of the eastern part of the river Po Valley. This group of hills stands out on the south-westerly horizon of the province of Padua, at approx. 60 kilometres from Venice and on a clear day the clock tower in St. Mark's Square can be seen from the top of Mount Gemola. The Euganean Hills cover a total area of approx. 19,000 hectares. The perimeter of the area is 65 kilometres, with around one hundred hills which reach a maximum height of 604 meters asl, as in the case of Mount Venda. The area is made up of 15 municipalities areas and since 1989 they have been protected by the Euganean Hills Regional Park authority. The hills were formed by a series of volcanic eruptions. The first activity dates at about 43 million years ago, but it was only the second volcanic phase, about 35 million years ago, that gave the region its present shape. From the the lava cooled down rocks like trachyte, rhyolite, latite, and strands of basalt were formed. The climate The climate is milder than that of the surrounding plain, in winter the thermometer doesn't drop below zero as frequently and for as long as it does in the plain. In summer it is cooler and less humid then the lowlands. This explains how the hills with a southern exposure, bathed by direct sunlight, can easily support vegetation like olive trees, cypresses, laurels, and other species of Mediterranean flora. -

Baone Anc Castelfranco, Italy

REPORT ON STUDY VISIT, TRAINING AND KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE SEMINAR IN VILLA BEATRICE D’ESTE (BAONE – Version 1 PADUA) AND CASTELFRANCO 04/2018 VENETO (TREVISO), ITALY D.T3.2.2 D.T3.5.1 D.T4.6.1 Table of Contents REPORT ON STUDY VISIT IN VILLA BEATRICE D’ESTE (BAONE - PADUA) on 07/03/2018…………….…. Page 3 1. ORGANISATIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING THE STUDY VISIT ........................................................................... 3 1.1. Agenda of study visit to Villa Beatrice d’Este, 07/03/2018 ................................................................................... 3 1.2. List of study visit participants .............................................................................................................................. 5 2. HISTORY OF VILLA BEATRICE D’ESTE ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.1. History of the property and reconstruction stages ............................................................................................... 6 2.2. Adaptations and conversions of some parts of the monastery............................................................................. 8 3. Characteristics of the contemporarily existing complex ........................................................................................ 12 3.1. Villa Beatrice d’Este and the surrounding areas - the current condition Characteristics of the area where the ruin is located ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Distretto Militare Di Padova- Ruoli Matricolari

Pe:.R K\C...M\Ei'6Efi!E. B,\JOl.0 ')\fì,8 O ... C\KE: 'b, \J\....'.) u fF1 �,R Lt-. o .::cl·-rn \ e P\\.E. 1 f<.IVoL�E.�..SI ?,F.,'f:.'5So L UFF1 -Gio- ----SICRI C ES(;..,:Zc., rio - \.J\� E1Rl)R 1� '1...:, o::d.8� Ro1if\ I lé.L. 06. 4-=f- ..55 �558 C'?. 4b 9-i 3-i 6 "::f ot0aR.1 F, ce� )tt:: \ \. J · �.,\ "Ft::.:.A CASE�MPt N�tAK O '......iA ' { · ,. U\f\ �?t'R\Ol?ì dLt RorlA o�. C..1- 3581.0b MINISTERO PER I BENI CULTURALI E AMBIENTALI ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI PADOVA UFFICIO LEVA DI PADOVA - DISTRETTO DI PADOVA Le liste di leva di Padova risultano divise per mandamento e per classe. Vi sono compresi anche i volumi relativi alle liste di revisioni dei riformati e rivedibili di Padova e provincia . 1 mandamenti (n.9) comprendono a loro volta un certo numero di comuni secondo la seguente suddivisione: 1. Mandamento di Camposampiero. Comprende i seguenti 15 comuni: · Borgoricco San Giorgio delle Pe1tiche Campo San Martino San Michele delle Badesse Campodarsego Sant'Eufemia Camposampiero Santa Giustina in Colle Cmtarolo Trebaseleghe · Loreggia Villa del Conte Massanzago Villanova di Camposampiero Piombino Dese - 2. Mandamento di Cittadella. Comprende i seguenti 10 comuni: Cittadella Gazzo Padovano Carmignano di Brenta San Giorgio in Bosco Fontaniva San Martino di Lupari Galliera Veneta San Pietro in Gù Grantorto Tombolo Classe 1857: Mandamento di CAMPOSAMPIERO n. 100 Mandamento di CITTADELLA n. 101 Mandamento di CONSELVE n. 102 Mandamento di ESTE n. 103 Mandamento di MONSELICE n. -

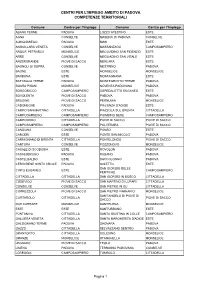

Centri Per L'impiego Ambito Di Padova Competenze Territoriali

CENTRI PER L'IMPIEGO AMBITO DI PADOVA COMPETENZE TERRITORIALI Comune Centro per l’Impiego Comune Centro per l’Impiego ABANO TERME PADOVA LOZZO ATESTINO ESTE AGNA CONSELVE MASERA' DI PADOVA CONSELVE ALBIGNASEGO PADOVA MASI ESTE ANGUILLARA VENETA CONSELVE MASSANZAGO CAMPOSAMPIERO ARQUA' PETRARCA MONSELICE MEGLIADINO SAN FIDENZIO ESTE ARRE CONSELVE MEGLIADINO SAN VITALE ESTE ARZERGRANDE PIOVE DI SACCO MERLARA ESTE BAGNOLI DI SOPRA CONSELVE MESTRINO PADOVA BAONE ESTE MONSELICE MONSELICE BARBONA ESTE MONTAGNANA ESTE BATTAGLIA TERME PADOVA MONTEGROTTO TERME PADOVA BOARA PISANI MONSELICE NOVENTA PADOVANA PADOVA BORGORICCO CAMPOSAMPIERO OSPEDALETTO EUGANEO ESTE BOVOLENTA PIOVE DI SACCO PADOVA PADOVA BRUGINE PIOVE DI SACCO PERNUMIA MONSELICE CADONEGHE PADOVA PIACENZA D'ADIGE ESTE CAMPO SAN MARTINO CITTADELLA PIAZZOLA SUL BRENTA CITTADELLA CAMPODARSEGO CAMPOSAMPIERO PIOMBINO DESE CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPODORO CITTADELLA PIOVE DI SACCO PIOVE DI SACCO CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPOSAMPIERO POLVERARA PIOVE DI SACCO CANDIANA CONSELVE PONSO ESTE CARCERI ESTE PONTE SAN NICOLO' PADOVA CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA CITTADELLA PONTELONGO PIOVE DI SACCO CARTURA CONSELVE POZZONOVO MONSELICE CASALE DI SCODOSIA ESTE ROVOLON PADOVA CASALSERUGO PADOVA RUBANO PADOVA CASTELBALDO ESTE SACCOLONGO PADOVA CERVARESE SANTA CROCE PADOVA SALETTO ESTE SAN GIORGIO DELLE CINTO EUGANEO ESTE CAMPOSAMPIERO PERTICHE CITTADELLA CITTADELLA SAN GIORGIO IN BOSCO CITTADELLA CODEVIGO PIOVE DI SACCO SAN MARTINO DI LUPARI CITTADELLA CONSELVE CONSELVE SAN PIETRO IN GU CITTADELLA CORREZZOLA PIOVE DI SACCO SAN PIETRO -

District 108TA3.Pdf

Club Health Assessment for District 108TA3 through December 2015 Status Membership Reports LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice No Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Active Activity Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Email ** Report *** Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs less than two years old 121893 Padova Galileo Galilei 04/16/2014 Active 24 0 0 0 0.00% 25 2 T 2 Clubs more than two years old 21027 ABANO TERME EUGANEE 11/10/1966 Active 38 0 1 -1 -2.56% 40 14 0 N 0 47788 ABANO TERME GASPARA 10/15/1987 Active 35 1 3 -2 -5.41% 33 7 0 N 0 STAMPA 56818 ARQUA' PETRARCA 04/17/1995 Active 20 0 0 0 0.00% 21 0 N 0 60304 BADIA POLESINE ADIGE PO 01/19/1998 Active 31 0 0 0 0.00% 30 0 N 0 59133 CADONEGHE GRATICOLATO 02/12/1997 Active 39 0 1 -1 -2.50% 17 10 0 2 N 0 ROMANO 21036 CAMPOSAMPIERO 02/16/1966 Active 63 2 2 0 0.00% 62 37 0 N 0 56849 CAORLE 04/24/1995 Active 33 0 0 0 0.00% 32 1 N 1 21043 CHIOGGIA SOTTOMARINA 04/09/1973 Active 34 0 2 -2 -5.56% 37 40 0 2 N 0 38336 CITTADELLA 04/07/1980 -

Geothermal State of Play Italy

Italy - State of the art of country and local situation Table of contents 1. Geothermal resources .......................................................................................................................................4 Geothermal potential ...................................................................................................................................4 Low-enthalpy geothermal potential ............................................................................................................5 Low-enthalpy geothermal reserves .............................................................................................................5 Location of geothermal reserves .................................................................................................................6 Hidrogeological considerations (lithology) .................................................................................................6 2. Geothermal exploitation installations ..............................................................................................................8 Locations of exploitation places ..................................................................................................................8 3. Hybrid geothermal installations .......................................................................................................................9 4. Case study ........................................................................................................................................................10 -

NOTIZIARIO PSN Nov-Dic-2018

PSNicolo novembre18_Layout 1 28/11/18 16:44 Pagina 1 STEFANO ZERBETTO EDITORE POSTE ITALIANE SPA - Sped. in abb. postale 45% - Art. 2 comma 20/b legge 662/96 - Filiale di Padova - N. 10/2018 Comune NOTIZIARIO COMUNALE e di Territorio Ponte San Nicolò www.comune.pontesannicolo.pd.it NOVEMBRE-DICEMBRE 2018 Numero 12 Progetto di recupero, ristrutturazione e ampliamento di Villa Crescente Studio di fattibilità e riqualificazione Studio di fattibilità per la riqualificazione del centro di Rio degli impianti sportivi di Rio Il sindaco: Maggioranza Associazioni un 2018 e opposizione e comunità SISTEMA QUALITÀ CERTIFICATO di grande consiliare di Ponte UNI EN ISO 9001 – CERT. n° 1977 impegno a confronto San Nicolò PSNicolo novembre18_Layout 1 28/11/18 16:44 Pagina 2 Il Piacere è: l’aroma di un buon caffè accompagnato dal gusto di un prodotto “Dolce Camilla” CAFFETTERIA PASTICCERIA PANIFICIO SERVIZIO RINFRESCHI A DOMICILIO TUTTO DI PONTE SAN NICOLÒ (PD) PRODUZIONE PROPRIA Via G. Marconi, 106/A Tel. e Fax 049 718341 OCCHIALI DI OGNI SPECIE! pronti in 15 minuti seguici su PONTE SAN NICOLÒ (Padova) Z.a. Roncajette - Viale Austria 4 Info 049 8962910 - [email protected] - www.outlet-occhiali.it PSNicolo novembre18_Layout 1 28/11/18 16:44 Pagina 3 S T EFANO ZERBETTO EDIT ORE POSTE ITALIANE SPA - Sped. in abb. postale 45% - Art. 2 comma 20/b legge 662/96 - Filiale di Padova - N. 10/2018 Comune NOTIZIARIO COMUNALE PONTE e di 3 SAN NICOLÒ Territorio Ponte San Nicolò www.comune.pontesannicolo.pd.it NOVEMBRE-DICEMBRE 2018 Numero 12 Progetto di recupero, -

ORARI SERVIZI AGGIUNTIVI PADOVA Aggiornati Al 1° Febbraio 2021

ORARI SERVIZI AGGIUNTIVI PADOVA aggiornati al 1° Febbraio 2021 Noi andiamo a scuola con Busitalia! POLO 3 Marconi, Bernardi, Selvatico, Ruzza, Calvi INDICE • La sicurezza viaggia con noi, e tu? pag. 3 • Urbano Padova pag. 5 • Legenda servizi aggiuntivi extraurbani pag. 6 • Elenco linee extraurbane potenziate pag. 7 • Extraurbano Padova pag. 8 • Informazioni e contatti pag. 15 2 LA SICUREZZA VIAGGIA CON NOI, E TU? INDOSSA CORRETTAMENTE LA NON METTERTI IN VIAGGIO SE HAI MASCHERINA A COPERTURA DI NASO E SINTOMI INFLUENZALI COME FEBBRE, BOCCA PRIMA DI SALIRE A BORDO E PER TOSSE, RAFFREDDORE. TUTTA LA DURATA DEL VIAGGIO. tolto un paio di parole SE IL BUS HA RAGGIUNTO LA PER VIAGGIARE, È NECESSARIO UN CAPIENZA MASSIMA DI PASSEGGERI REGOLARE TITOLO DI VIAGGIO. CONSENTITA, INDICATA NELLA ACQUISTALO PRIMA DI SALIRE A BORDO, XX SEGNALETICA SULLA PORTA DI SE IL BUS HA RAGGIUNTO LA CAPIENZA PRIVILEGIANDO I CANALI DIGITALI. MASSIMAACCESSO, DI PASSEGGERI ATTENDI IL CONSENTITA,BUS SUCCESSIVO. 50 50 3 LA SICUREZZA VIAGGIA CON NOI, E TU? RISPETTA LA DISTANZA DI SICUREZZA RICORDA DI IGIENIZZARE ALLE FERMATE E A BORDO. FREQUENTEMENTE LE MANI UTILIZZANDO GLI APPOSITI DISPENCER. NON AVVICINARTI ALL’AUTISTA PER CHIEDERE INFORMAZIONI E RICORDA NON UTILIZZARE I CHE LA VENDITA A BORDO DEI TITOLI POSTI CONTRASSEGNATI. DI VIAGGIO È SOSPESA. 4 URBANO PADOVA - orari servizi aggiuntivi LINEE URBANE | LUNEDI' - VENERDI' Linea Descrizione Percorso Ora Da Ora A NAVU24 Mandriola Prato della Valle Severi 07:05 08:00 U13 Altichiero - Prato della Valle 07:05 07:40 U13 Prato della Valle Altichiero 13:45 14:10 U13 Prato della Valle - Limena 14:25 15:15 U16 Roncajette - Prato della Valle 06:55 07:35 U16 Ponte S. -

Discover Padua and Its Surroundings

2647_05_C415_PADOVA_GB 17-05-2006 10:36 Pagina A Realized with the contribution of www.turismopadova.it PADOVA (PADUA) Cittadella Stazione FS / Railway Station Porta Bassanese Tel. +39 049 8752077 - Fax +39 049 8755008 Tel. +39 049 9404485 - Fax +39 049 5972754 Galleria Pedrocchi Este Tel. +39 049 8767927 - Fax +39 049 8363316 Via G. Negri, 9 Piazza del Santo Tel. +39 0429 600462 - Fax +39 0429 611105 Tel. +39 049 8753087 (April-October) Monselice Via del Santuario, 2 Abano Terme Tel. +39 0429 783026 - Fax +39 0429 783026 Via P. d'Abano, 18 Tel. +39 049 8669055 - Fax +39 049 8669053 Montagnana Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 Castel S. Zeno Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 Tel. +39 0429 81320 - Fax +39 0429 81320 (sundays opening only during high season) Teolo Montegrotto Terme c/o Palazzetto dei Vicari Viale Stazione, 60 Tel. +39 049 9925680 - Fax +39 049 9900264 Tel. +39 049 8928311 - Fax +39 049 795276 Seasonal opening Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 nd TREVISO 2 Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 AIRPORT (sundays opening only during high season) MOTORWAY EXITS Battaglia Terme TOWNS Via Maggiore, 2 EUGANEAN HILLS Tel. +39 049 526909 - Fax +39 049 9101328 VENEZIA Seasonal opening AIRPORT DIRECTION TRIESTE MOTORWAY A4 Travelling to Padua: DIRECTION MILANO VERONA MOTORWAY A4 AIRPORT By Air: Venice, Marco Polo Airport (approx. 60 km. away) By Rail: Padua Train Station By Road: Motorway A13 Padua-Bologna: exit Padua Sud-Terme Euganee. Motorway A4 Venice-Milano: exit Padua Ovest, Padua Est MOTORWAY A13 DIRECTION BOLOGNA adova. -

Padua Demo, Fstechnology

PADUA DEMO Stakeholder Meeting – 2nd Feb 2021 Riccardo Santoro, Alessandra Berto, Marco Tognaccini, Albino Penna, Simone Salviati This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 881825. Informazione ad uso interno KEY ACTORS FROM FSI GROUP IN R2R PROJECT R2R Partner FSTechnology (owned by the “Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane – FSI” Group) is one of the partners of the Ride2Rail Project. FSTechnology is the IT service provider of the FSI Group, dedicated to technology and innovation. Through commercial applications, as App Trenitalia and Viaggiatreno, and data managed by NUGO App, it can easily manage an integrated commercial platform for electronic ticketing, booking, infomobility. FST Supporting Partners Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane SpA, one of the largest company in Italy, controls its operating companies in the four sectors of supply chain, transport, infrastructure, real estate services and other services, and, notwithstanding the independent legal responsibilities of the individual companies, carries out activities of an organisational nature that are typical of a holding company (the management of shares, shareholding control, etc.), as well as those of an industrial nature. Busitalia Veneto S.p.A. is the company operating in Veneto offering urban and extra-urban mobility services in the provinces of Padua and Rovigo NUGO, company part of the FSI Group, is the application for shared mobility that provides planning, information, one-stop-shop services through a network of strategic agreements with local TSPs 2 Informazione ad uso interno Contract No. 881825 PADUA DEMO OVERVIEW Objective The demo has the purpose to demonstrate RIDE2RAIL functionalities in a real-life environment, a 20 Km area surrounding the city of Padua (Italy) with regular commuter flows from/to suburban and rural areas. -

Le Elezioni Comunali 2017 in Veneto

CONSIGLIO REGIONALE DEL VENETO LE ELEZIONI COMUNALI 2017 IN VENETO REPORT RISULTATI DEFINITIVI 26 giugno 2017 CONSIGLIO REGIONALE DEL VENETO INDICE DEI CONTENUTI AFFLUENZA ALLE URNE AL PRIMO TURNO ........................................................................................................ 3 AFFLUENZA ALLE URNE AL SECONDO TURNO ................................................................................................... 6 RISULTATI DELLE ELEZIONI ................................................................................................................................ 7 PROVINCIA DI BELLUNO ................................................................................................................................ 7 PROVINCIA DI PADOVA ................................................................................................................................ 13 PROVINCIA DI ROVIGO ................................................................................................................................ 22 PROVINCIA DI TREVISO ................................................................................................................................ 25 PROVINCIA DI VENEZIA ................................................................................................................................ 32 PROVINCIA DI VERONA ................................................................................................................................ 39 PROVINCIA DI VICENZA...............................................................................................................................