Debussy in Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debussy's Pelléas Et Mélisande

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore Pelléas et Mélisande is a strange, haunting work, typical of the Symbolist movement in that it hints at truths, desires and aspirations just out of reach, yet allied to a longing for transcendence is a tragic, self-destructive element whereby everybody suffers and comes to grief or, as in the case of the lovers, even dies - yet frequent references to fate and Arkel’s ascribing that doleful outcome to ineluctable destiny, rather than human weakness or failing, suggest that they are drawn, powerless, to destruction like moths to the flame. The central enigma of Mélisande’s origin and identity is never revealed; that riddle is reflected in the wispy, amorphous property of the music itself, just as the text, adapted from Maeterlinck’s play, is vague and allusive, rarely open or direct in its expression of the characters’ velleities. The opera was highly innovative and controversial, a gateway to a new style of modern music which discarded and re-invented operatic conventions in a manner which is still arresting and, for some, still unapproachable. It is a work full of light and shade, sunlit clearings in gloomy forest, foetid dungeons and sea-breezes skimming the battlements, sparkling fountains, sunsets and brooding storms - all vividly depicted in the score. Any francophone Francophile will delight in the nuances of the parlando text. There is no ensemble or choral element beyond the brief sailors’ “Hoé! Hisse hoé!” offstage and only once do voices briefly intertwine, at the climax of the lovers' final duet. -

Jules Massenet Werther Nedjelja, 16

Jules Massenet WERTHER Nedjelja, 16. ožujka 2014., 18 sati. Foto: Metropolitan opera Jules Massenet WERTHER Nedjelja, 16. ožujka 2014., 18 sati. SNIMKA THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Jules Massenet WERTHER Opera u četiri čina Libreto: Edouard Blau, Paul Milliet i Georges Hartmann prema romanu u pismima Patnje mladog Werthera Leiden des jungen Werthers Johanna Wolfganga von Goethea NEdjEljA, 16. OžUjkA 2014. POčETAK U 18 SATI. Praizvedba: Dvorska opera, Beč, 16. veljače 1892. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Hrvatsko zemaljsko kazalište, Zagreb, 29. listopada 1901. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 29. ožujka 1894. Premijera ove produkcije: 18. veljače 2014. CHARLOTTE Sophie Koch SCHMIDT Tony Stevenson SOPHIE Lisette Oropesa JOHANN Philip Cokorinos WERTHER Jonas Kaufmann KÄTCHEN Maya Lahyani ALBERT David Bizic SOLISTI Dječji zbor Metropolitana NačeLNIK /LE BAILLI Jonathan Summers ZBorovođa Anthony Piccolo Foto:Metropolitan opera ORKESTAR METROPOLITANA OBLIKOVATELJ RASVJETE Peter Mumford DIRIGENT Alain Altinoglu VIDEO PROJEKCIJE Wendall Harrington REDATELJ Richard Eyre KOREOGRAFKINJA Sara Erde SCENOGRAF I KOSTIMOGRAF Rob Howell Stanka nakon drugoga čina. Svršetak oko 21 sat i 15 minuta. Tekst: francuski. Titlovi: engleski. Foto:Metropolitan opera PRVI ČIN – Načelnikova kuća pjevati himnu ljepoti prirode - „O Nature, Prvi čin događa se u idiličnom ugođaju pleine de grâce“ - i sav taj prizor izvrsno Načelnikove kuće u Wetzlaru sedamdesetih odražava idilu iskrenog zanosa. Massenetovi godina 18. stoljeća. Ljeto je. Načelnik s libretisti crpili su nadahnuće za nju iz drugoga najmlađom djecom uvježbava božićne pjesme. -

"Gioconda" Rings Up-The Curtain At

Vol. XIX. No. 3 NEW YORK EDITED ~ ~ ....N.O.V.E.M_B_E_R_2_2 ,_19_1_3__ T.en.~! .~Ot.~:_:r.rl_::.: ... "GIOCONDA" RINGS "DON QUICHOTTE"HAS UP- THE CURTAIN AMERICANPREMIERE AT METROPOLITAN Well Performed by Chicago Com pany in Philadelphia- Music A Spirited Performance with Ca in Massenet's Familiar Vein ruso in Good 'Form at Head B ureau of Musical A m erica, of the Cas t~Amato, Destinn Sixt ee nth and Chestn ut Sts., Philadel phia, Novem ber 17. 1913.. and Toscanini at Their Best T HE first real novelty of the local opera Audience Plays Its Own Brilliant season was offered at the Metropolitan Part Brilliantly-Geraldine Far last Saturday afternoon, when Mas senet's "Don Quichotte" had its American rar's Cold Gives Ponchielli a premiere, under the direction of Cleofonte Distinction That Belonged to Campanini, with Vanni Marcoux in the Massenet title role, which he had sung many times in Europe; Hector Dufranne as Sancho W ITH a spirited performance of "Gio- Panza, and Mary Garden as La Belle Dul conda" the Metropolitan Opera cinea. The performance was a genuine Company began its season last M'o;day success. The score is in Massenet's fa night. The occasion was as brilliant as miliar vein: It offers a continuous flow of others that have gone before, and if it is melody, light, sometimes almost inconse quential, and not often of dramatic signifi not difficult to recall premieres of greater cance, but at all times pleasing, of an ele artistic pith and moment it behooves the gance that appeals to the aesthetic sense, chronicler of the august event to record and in all its phases appropriate to the the generally diffused glamor as a matter story, sketched rather briefly by Henri Cain from the voluminous romance of Miguel de of necessary convention, As us~al there Cervantes. -

2Cd Set Songs to the Moon Cd2

2CD SET SONGS TO THE MOON CD2 1 Nocturne, Op. 13 No. 4 MF Samuel Barber [3.32] 2 Sun, Moon and Stars MB Elizabeth Maconchy [3.51] CD1 3 Clair de lune, Op. 83 No. 1 AC Joseph Szulc [3.25] 1 The Night AC Peter Warlock [2.11] 4 Damunt de tu només les flors CM Federico Mompou [4.22] 5 Guitares et mandolines MF Camille Saint-Saëns [1.49] 2 Nächtens, Op. 112 No. 2 MB CM AC MF Johannes Brahms [1.45] 6 Apparition MB Claude Debussy [3.48] 3 Vor der Tür, Op. 28 No. 2 MB MF Johannes Brahms [1.58] 7 La nuit, Op. 11 No. 1 MB MF Ernest Chaussan [2.47] 4 Unbewegte laue Luft, Op. 57 No. 8 MF Johannes Brahms [4.07] 8 L’heure exquise CM Reynaldo Hahn [2.51] 5 Der Gang zum Liebchen, Op. 31 No. 3 MB CM AC MF Johannes Brahms [3.14] 9 La fuite CM MF Henri Duparc [3.15] 6 Walpurgisnacht, Op. 75 No. 4 MB CM Johannes Brahms [1.32] 0 7 Rêvons, c’est l’heure MB CM Jules Massenet [5.04] Ständchen, Op. 106 No. 1 CM Johannes Brahms [1.43] 8 Der Abend, Op. 64 No. 2 MB CM AC MF Johannes Brahms [3.51] q Clair de lune, Op. 46 No. 2 AC Gabriel Fauré [2.56] 9 Vergebliches Ständchen, Op. 84 No. 4 CM MF Johannes Brahms [1.43] w Pleurs d’or, Op. 72 AC MF Gabriel Fauré [2.47] e 0 Tarentelle, Op. -

The Mezzo-Soprano Onstage and Offstage: a Cultural History of the Voice-Type, Singers and Roles in the French Third Republic (1870–1918)

The mezzo-soprano onstage and offstage: a cultural history of the voice-type, singers and roles in the French Third Republic (1870–1918) Emma Higgins Dissertation submitted to Maynooth University in fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Maynooth University Music Department October 2015 Head of Department: Professor Christopher Morris Supervisor: Dr Laura Watson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page number SUMMARY 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 LIST OF FIGURES 5 LIST OF TABLES 5 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER ONE: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO AS A THIRD- 19 REPUBLIC PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN 1.1: Techniques and training 19 1.2: Professional life in the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique 59 CHAPTER TWO: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO ROLE AND ITS 99 RELATIONSHIP WITH THIRD-REPUBLIC SOCIETY 2.1: Bizet’s Carmen and Third-Republic mores 102 2.2: Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila, exoticism, Catholicism and patriotism 132 2.3: Massenet’s Werther, infidelity and maternity 160 CHAPTER THREE: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO AS MUSE 188 3.1: Introduction: the muse/musician concept 188 3.2: Célestine Galli-Marié and Georges Bizet 194 3.3: Marie Delna and Benjamin Godard 221 3.3.1: La Vivandière’s conception and premieres: 1893–95 221 3.3.2: La Vivandière in peace and war: 1895–2013 240 3.4: Lucy Arbell and Jules Massenet 252 3.4.1: Arbell the self-constructed Muse 252 3.4.2: Le procès de Mlle Lucy Arbell – the fight for Cléopâtre and Amadis 268 CONCLUSION 280 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 APPENDICES 305 2 SUMMARY This dissertation discusses the mezzo-soprano singer and her repertoire in the Parisian Opéra and Opéra-Comique companies between 1870 and 1918. -

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1 Renata Suchowiejko ( Jagiellonian University, Kraków) [email protected] The 20-year interwar period was a crucial time for Polish music. After Poland regained independence in 1918, the development of Polish musical culture was supported by government institutions. Infrastructure serving the concert life and the education system considerably improved along with the development of mass media and printing industries. International co-operation also got reinvigorated. New societies, associations and institutions were established to promote Polish culture abroad. And the mobility of musicians considerably increased. At that time the preferred destination of the artists’ rush was Paris. The journeys were taken mostly by young musicians in their twenties or thirties. Amongst them were instrumentalists, singers and directors who wished to improve their performance skills and to try their skills before the public of concert halls. Composers wanted to taste the musical climate of the metropolis and to learn the latest trends in music of that time. They strongly believed that 1. This paper has been prepared within the framework of the research programme Presence of Polish Music and Musicians in the Artistic Life of Interwar Paris, supported from the means of the National Science Centre, Poland, OPUS programme, under contract No. UMO-2016/23/B/ HS2/00895. The final effect of the project is the publication of a study Muzyczny Paryż à la polonaise w okresie międzywojennym. Artyści – Wydarzenia – Konteksty [Musical Paris à la polonaise In the Interwar Period: Artists – Events – Contexts] by Renata Suchowiejko, Kraków, Księgarnia Akademicka, 2020. -

[ News and Comment of Concert and Opera I To-Night

NEWS AND ___-;-,1- . COMMENT OF AND I [ .=============^_-_-___^^^-:-1^5^----= =____-_ CONCERT OPERA cnt-day desolation and destruction in . -'.-" a uatanic fury. The artist will lccturo \Chicago Opera Co, on the exhibition of thrilling scenes, all of which wcro made in their natural Mme. to Sing colors a new Hempel by process. Tho former ' Last Week Minister of War, M. Millcrand, is the I Begins executive president of the Committee in 'Le Nozze di for tho Relief of the Wounded and Sick Figaro Presentation Will Include Soldiers. President Poincaró is chair¬ Two Operas man of tho honorary committee. Will- Caruso To Be Heard as Radames in New to New York Audiences: (iLeSau- Jam Saneloz was sent to this country aa a special commissioner in charge of and teriot," by Lazzari, and <(Isabeau,T the exhibition. "Aida," Lázaro, Spanish Tenor, Tho American executive committee is Will headed by Mrs. Robert Appear 'Again in "Rigoletto" fourth and la^t week of the Chi- Bacon and Mrs. The which Rosa LeRoy Edgar. Th« list of season at the Raisa, Giuseppi Gandcnzi, patronesses rneo Opera Company's Giacomo Rimini, Louise at tho French Theatre exhibition in¬ i Mme. Frieda lícmpcl will make lier will dance. Mr. Bodanzky will conduct. Theatre will include two op¬ Swartz Berat, Jcska Lexington and others of its former cast cludes over fifty prominent last appearance this season with the "Mrfrouf" will be the'Saturday mat¬ eras new to New York, which had their will society appear, with M. Charlier at women. Among them are Mrs. -

Cohesion of Composer and Singer: the Female Singers of Poulenc

COHESION OF COMPOSER AND SINGER: THE FEMALE SINGERS OF POULENC DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susan Joanne Musselman, B.M., M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Document Committee: J. Robin Rice, Adviser Approved by: Hilary Apfelstadt Wayne Redenbarger ________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Music Copyright by Susan Joanne Musselman 2007 ABSTRACT Every artist’s works spring from an aspiring catalyst. One’s muses can range from a beloved city to a spectacular piece of music, or even a favorite time of year. Francis Poulenc’s inspiration for song-writing came from the high level of intimacy he had with his close friends. They provided the stimulation and encouragement needed for a lifetime of composition. There is a substantial amount of information about Francis Poulenc’s life and works available. We are fortunate to have access to his own writings, including a diary of his songs, an in-depth interview with a close friend, and a large collection of his correspondence with friends, fellow composers, and his singers. It is through these documents that we not only glean knowledge of this great composer, but also catch a glimpse of the musical accuracy Poulenc so desired in the performance of his songs. A certain amount of scandal surrounded Poulenc during his lifetime and even well after his passing. Many rumors existed involving his homosexuality and his relationships with other male musicians, as well as the possible fathering of a daughter. The primary goal of this document is not to unearth any hidden innuendos regarding his personal life, however, but to humanize the relationships that Poulenc had with so many of his singers. -

Tailor-Made: Does This Song Look Good on Me? the Voices That Inspired Vocal Music History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: TAILOR-MADE: DOES THIS SONG LOOK GOOD ON ME? THE VOICES THAT INSPIRED VOCAL MUSIC HISTORY Theresa Rose Bickham, Doctor of Musical Arts in Vocal Performance, 2019 Dissertation directed by: Professor Carmen Balthrop, School of Music The history of tailor-made repertoire is celebrated, and, in many cases, the composer and the works live on in perpetuity while the performing artist is remembered only in historical documents. Timbres, agilities, ranges, and personalities of singers have long been a source of inspiration for composers. Even Mozart famously remarked that he wrote arias to fit singers like a well-tailored suit. This dissertation studies the vocal and dramatic profiles of ten sopranos and discovers how their respective talents compelled famed composers to create music that accommodated each singer’s unique abilities. The resulting repertoire advanced the standard of vocal music and encouraged new developments in the genres and styles of compositions for the voice. This is a performance dissertation and each singer is depicted through the presentation of repertoire originally created for and by them. The recital series consisted of one lecture recital and two full recitals performed at the University of Maryland, College Park. I was joined in the performance of these recitals by pianist Andrew Jonathan Welch, clarinetist Melissa Morales, and composer/pianist Dr. Elaine Ross. The series was presented chronologically, and the first recital included works of the Baroque and Classical music eras written for Marie Le Rochois, Faustina Bordoni, Catarina Cavalieri, and Adriana Ferrarese del Bene. The second recital advanced into the nineteenth-century with repertoire composed for Anna Milder-Hauptmann, Giulia Grisi, and Mary Garden. -

Maurice Ravel Chronology

Maurice Ravel Chronology by Manuel Cornejo 2018 English Translation by Frank Daykin Last modified date: 10 June 2021 With the kind permission of Le Passeur Éditeur, this PDF, with some corrections and additions by Dr Manuel Cornejo, is a translation of: Maurice Ravel : L’intégrale : Correspondance (1895-1937), écrits et entretiens, édition établie, présentée et annotée par Manuel Cornejo, Paris, Le Passeur Éditeur, 2018, p. 27-62. https://www.le-passeur-editeur.com/les-livres/documents/l-int%C3%A9grale In order to assist the reader in the mass of correspondence, writings, and interviews by Maurice Ravel, we offer here some chronology which may be useful. This chronology attempts not only to complete, but correct, the existent knowledge, notably relying on the documents published herein1. 1 The most recent, reliable, and complete chronology is that of Roger Nichols (Roger Nichols, Ravel: A Life, New Haven, Yale University, 2011, p. 390-398). We have attempted to note only verifiable events with documentary sources. Consultation of many primary sources was necessary. Note also the account of the travels of Maurice Ravel made by John Spiers on the website http://www.Maurice Ravel.net/travels.htm, which closed down on 31 December 2017. We thank in advance any reader who may be able to furnish us with any missing information, for correction in the next edition. Maurice Ravel Chronology by Manuel Cornejo English translation by Frank Daykin 1832 19 September: birth of Pierre-Joseph Ravel in Versoix (Switzerland). 1840 24 March: birth of Marie Delouart in Ciboure. 1857 Pierre-Joseph Ravel obtains a French passport. -

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1 Renata Suchowiejko ( Jagiellonian University, Kraków) [email protected] The 20-year interwar period was a crucial time for Polish music. After Poland regained independence in 1918, the development of Polish musical culture was supported by government institutions. Infrastructure serving the concert life and the education system considerably improved along with the development of mass media and printing industries. International co-operation also got reinvigorated. New societies, associations and institutions were established to promote Polish culture abroad. And the mobility of musicians considerably increased. At that time the preferred destination of the artists’ rush was Paris. The journeys were taken mostly by young musicians in their twenties or thirties. Amongst them were instrumentalists, singers and directors who wished to improve their performance skills and to try their skills before the public of concert halls. Composers wanted to taste the musical climate of the metropolis and to learn the latest trends in music of that time. They strongly believed that 1. This paper has been prepared within the framework of the research programme Presence of Polish Music and Musicians in the Artistic Life of Interwar Paris, supported from the means of the National Science Centre, Poland, OPUS programme, under contract No. UMO-2016/23/B/ HS2/00895. The final effect of the project is the publication of a study Muzyczny Paryż à la polonaise w okresie międzywojennym. Artyści – Wydarzenia – Konteksty [Musical Paris à la polonaise In the Interwar Period: Artists – Events – Contexts] by Renata Suchowiejko, Kraków, Księgarnia Akademicka, 2020. -

18.5 Vocal 78S. Sagi-Barba -Zohsel, Pp 135-170

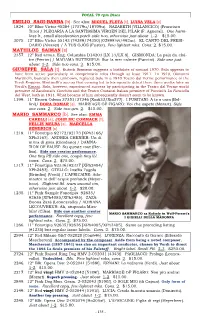

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs EMILIO SAGI-BARBA [b]. See also: MIGUEL FLETA [t], LUISA VELA [s] 1824. 10” Blue Victor 45284 [17579u/18709u]. NAZARETH [VILLANCICO] (Francisco Titto) / PLEGARIA A LA SANTISSIMA VIRGEN DEL PILAR (F. Agüeral). One harm- less lt., small discoloration patch side two, otherwise just about 1-2. $15.00. 3075. 12” Blue Victor 55143 (74389/74350) [02898½v/492ac]. EL CANTO DEL PRESI- DARIO (Alvarez) / Á TUS OJOS (Fuster). Few lightest mks. Cons . 2. $15.00. MATHILDE SAIMAN [s] 2357. 12” Red acous. Eng. Columbia D14203 [LX 13/LX 8]. GISMONDA: La paix du cloï- tre (Février) / MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Sur la mer calmée (Puccini). Side one just about 1-2. Side two cons . 2. $15.00. GIUSEPPE SALA [t]. Kutsch-Riemens suggests a birthdate of around 1870. Sala appears to have been active particularly in comprimario roles through at least 1911. 1n 1910, Giovanni Martinelli, basically then unknown, replaced Sala in a 1910 Teatro dal Verme performance of the Verdi Requiem . Martinelli’s sucess that evening led to his operatic debut there three weeks later as Verdi’s Ernani. Sala, however, experienced success by participating in the Teatro dal Verme world premiere of Zandonai’s Conchita and the Teatro Costanzi Italian premiere of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West , both in 1911. What became of him subsequently doesn’t seem to be known. 1199. 11” Brown Odeon 37351/37346 [Xm633/Xm577]. I PURITANI: A te o cara (Bel- lini)/ DORA DOMAR [s]. MARRIAGE OF FIGARO: Voi che sapete (Mozart). Side one cons. 2. Side two gen . 2.