Tailor-Made: Does This Song Look Good on Me? the Voices That Inspired Vocal Music History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

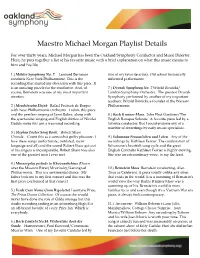

Michael Morgan Playlist

Maestro Michael Morgan Playlist Details For over thirty years, Michael Morgan has been the Oakland Symphony Conductor and Music Director. Here, he puts together a list of his favorite music with a brief explanation on what this music means to him and his life. 1.) Mahler Symphony No. 7. Leonard Bernstein two of my favorite artists. Old school historically conducts New York Philharmonic. This is the informed performance. recording that started my obsession with this piece. It is an amazing puzzle for the conductor. And, of 7.) Dvorak Symphony No. 7 Witold Rowicki/ course, Bernstein was one of my most important London Symphony Orchestra. The greatest Dvorak mentors. Symphony performed by another of my important teachers: Witold Rowicki, a founder of the Warsaw 2.) Mendelssohn Elijah. Rafael Frubeck de Burgos Philharmonic. with New Philharmonia Orchestra. I adore this piece and the peerless singing of Janet Baker, along with 8.) Bach B minor Mass. John Eliot Gardiner/The the spectacular singing and English diction of Nicolai English Baroque Soloists. A favorite piece led by a Gedda make this just a treasured recording. favorite conductor. But I could endorse any of a number of recordings by early music specialists. 3.) Stephen Foster Song Book. Robert Shaw Chorale. Count this as a somewhat guilty pleasure. I 9.) Schumann Frauenlieben und Leben. Any of the love these songs (unfortunate, outdated, racist recordings by Kathleen Ferrier. The combination of language and all) and the sound Robert Shaw got out Schumann's heartfelt song cycle and the great of his singers is incomparable. Robert Shaw was also English Contralto Kathleen Ferrier is highly moving. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Francesco Cavalli

OPÉRA DE MONTPELLIER Francesco Cavalli Opéra de Montpellier Ville de 11, boulevard Victor Hugo - CS 89024 - 34967 Montpellier Cedex 2 Montpellier Tél. 04 67 60 19 99 Fax 04 67 60 19 90 Adresse Internet : http://www.opera-montpellier.com — Email : [email protected] La Didone OPÉRA EN UN PROLOGUE ET TROIS ACTES DE FRANCESCO CAVALLI LIVRET DE FRANCESCO BUSENELLO CRÉATION A VENISE EN 1641 AU THEATRE SAN CASSIANO. PRODUCTION DE L'OPÉRA DE LAUSANNE 18, 20 et 21 janvier 2002 à l'Opéra Comédie Les Talens Lyriques Choeurs de l'Opéra de La Didone Direction, clavecin et orgue Montpellier Christophe Rousset Direction musicale Didone, Creusa, Ombra di Creusa Franck Bard Christophe Rousset Juanita Lascarro ORCHESTRE Marie-Anne Benavoli Fialho Direction des choeurs Violons Elina Bordry Enea Enrico Gatti, Nathalie Cazenave Noêlle Geny Topi Lehtipuu Gilone Gaubert-Jacques Eric Chabrol Altos Christian Chauvot Réalisation larba Judith Depoutot, Ernesto Fuentes Mezco Éric Vigner Ivan Ludlow Jun Okada Josiane Houpiez-Bainvel Étienne Leclercq Costumes Flûtes à bec Paul Quenson Anna, Cassandra Jacques Maresch Héloïse Gaillard, Katalin Varkonyi Hervé Martin Lumières Meillane Wilmotte Christophe Delarue Jean-Claude Pacuil Venere, una damigella Cornets Béatrice Parmentier Anne-Lise Sollied Frithjof Smith, Sherri Sassoon-Deschler David Gebhard, Dramaturgie et surtitres Olga Tichina Rita de Letteriis Doron Sherwin Ascanio, Amore Trombones Assistant à la direction musicale Valérie Gabail Jean-Marc Aymes Franck Poitrineau, Junon, una damigella Stefan Legée, -

Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, L. C.(2019). Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5248 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher by Lara C. Wilson Bachelor of Music Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 1991 Master of Music Indiana University, 1997 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: E. Jacob Will, Major Professor J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Lynn Kompass, Committee Member Janet Hopkins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Lara C. Wilson, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my family, David, Dawn and Lennon Hunt, who have given their constant support and unconditional love. To my Mom, Frances Wilson, who has encouraged me through this challenge, among many, always believing in me. Lastly and most importantly, to my husband Andy Hunt, my greatest fan, who believes in me more sometimes than I believe in myself and whose backing has been unwavering. -

Female Soprano Roles in Handel's Operas Simple

Female Soprano Roles in Handel's 39 Operas compiled by Jennifer Peterson, operamission a recommended online source for plot synopses Key Character Singer who originated role # of Arias/Ariosos/Duets/Accompagnati Opera, HWV (Händel-Werke-Verzeichnis) Almira, HWV 1 (1705) Almira unknown 8/1/1/2 Edilia unknown 4/1/1/0 Bellante unknown 2/2/1/1 NOTE: libretto in both German and Italian Rodrigo, HWV 5 (1707) Esilena Anna Maria Cecchi Torri, "La Beccarina" 7/1/1/1 Florinda Aurelia Marcello 5/1/0/0 Agrippina, HWV 6 (1709) Agrippina Margherita Durastanti 8/0/0 (short quartet)/0 Poppea Diamante Maria Scarabelli 9/0/0 (short trio)/0 Rinaldo, HWV 7 (1711) Armida Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti, "Pilotti" 3/1/2/1 Almirena Isabella Girardeau 3/1/1/0 Il Pastor Fido, HWV 8 (1712) Amarilli Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti, "Pilotti" 3/0/1/1 Eurilla Francesca Margherita de l'Épine, "La Margherita" 4/1/0/0 Page 1 of 5 Teseo, HWV 9 (1712) Agilea Francesca Margherita de l'Épine, "La Margherita" 7/0/1/0 Medea – Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti, "Pilotti" 5/1/1/2 Clizia – Maria Gallia 2/0/2/0 Silla, HWV 10 (?1713) Metella unknown 4/0/0/0 Flavia unknown 3/0/2/0 Celia unknown 2/0/0/0 Amadigi di Gaula, HWV 11 (1715) Oriana Anastasia Robinson 6/0/1/0 Melissa Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti, "Pilotti" 5/1/1/0 Radamisto, HWV 12 (1720) Polissena Ann Turner Robinson 4/1/0/0 Muzio Scevola, HWV 13 (1721) Clelia Margherita Durastanti 2/0/1/1 Fidalma Maddalena Salvai 1/0/0/0 Floridante, HWV 14 (1721) Rossane Maddalena Salvai 5/1/1/0 Ottone, HWV 15 (1722) Teofane Francesca -

RSTD OPERN Ma Rz April Ok 212X433

RSTD OPERN_März April_ok_212x433 12.02.13 09:40 Seite 1 Opernprogramm März 2013 März Gaetano Donizetti Anna Bolena 20.00 - 22.55 Anna Bolena: Edita Gruberova, Giovanna Seymour: Delores Ziegler, Enrico VIII.: Stefano Palatchi, Lord Rochefort: Igor Morosow, 2 Lord Riccardo Percy: José Bros, Smeton: Helene Schneiderman, Sir Hervey: José Guadalupe Reyes. Samstag Chor und Orchester des Ungarischen Rundfunks und Fernsehens, Leitung: Elio Boncompagni, 1994. März Richard Wagner Das Liebesverbot 20.00 - 22.40 Friedrich: Hermann Prey, Luzio: Wolfgang Fassler, Claudio: Robert Schunk, Antonio: Friedrich Lenz, Angelo: Kieth Engen, 5 Isabella: Sabine Hass, Mariana: Pamela Coburn, Brighella: Alfred Kuhn. Dienstag Chor der Bayerischen Staatsoper, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Leitung: Wolfgang Sawallisch, 1983. März Georg Friedrich Händel Alessandro 20.00 - 23.20 Alessandro Magno: Max Emanuel Cencic, Rossane: Julia Lezhneva, Lisaura: Karina Gauvin, Tassile: Xavier Sabata, 7 Leonato: Juan Sancho, Clito: In-Sung Sim, Cleone: Vasily Khoroshev. Donnerstag The City of Athens Choir, Armonia Atenea, Leitung: George Petrou, 2011. März Giuseppe Verdi Aroldo 20.00 - 22.15 Aroldo: Neil Shicoff, Mina: Carol Vaness, Egberto: Anthony Michaels-Moore, Briano: Roberto Scandiuzzi, 9 Godvino: Julian Gavin, Enrico: Sergio Spina, Elena: Marina Comparato. Samstag Coro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Leitung: Zubin Mehta, 2001. März Wolfgang Amadé Mozart La finta giardiniera 20.00 - 23.10 Sandrina: Sophie Karthäuser, Contino Belfiore: Jeremy Ovenden, Arminda: Alex Penda, 12 Cavaliere Ramiro: Marie-Claude Chappuis, Podestà: Nicolas Rivenq, Serpetta: Sunhae Im, Roberto: Michael Nagy. Dienstag Freiburger Barockorchester, Leitung: René Jacobs, 2011. Der neue Konzertzyklus im Mozarthaus Vienna: mozartakademie 2013 „Magic Moments – Magische Momente in den Werken großer Meister“ 20.03. -

President Douglas M. Knight Resigns from Lawrenci1 Ex-Yale Professor Accepts Duke University Presidency 7 Lawrentfanpresident Douglas Maitland Knight of Lawrence Voi

President Douglas M. Knight Resigns from Lawrenci1 Ex-Yale Professor Accepts Duke University Presidency 7 LawrentfanPRESIDENT Douglas Maitland Knight of Lawrence Voi. 82— No. 7 Lawrence College, Appleton, Wis. Fri., Nov. 2, 1962 college was named fifth president of Duke university this morning at a meeting of the Duke board of trust Anthony Wedgwood Benn ees in Durham, N. C. Dr. Knight was in Durham for the meeting. The election of the 41-year old Yale- trained President Knight cli- rnaxed a nation-wide search Knight also has edited and British Politician to Speak on the part of a trustee Pres written several chapters of a idential Selection Committee, book. “The Federal Govern of which Wright Tisdale, ment and Higher Educa At Convocation Thursday Dearborn. Mich., was chair tion, brought out by the ANTHONY WEDGWOOD BENN, the brilliant and man. The Duke trustees have American Assembly in 1960. newsmaking young British politician, will speak in been discussing the matter At Lawrence. Knight’s nine convocation on Thursday, Nov. 8. The topic of his with President Knight since years have brought about a summer. speech will be “Report from London.” 100 |H*r cent increase in the ACCORDING to the an book value of the college phy Elected to the House of Commons at the age of 25 nouncement by B u n y a n sical plant and a 150 per cent in 1950, Benn was returned to Snipes Womble, chairman of increase in the hook value Parliament three times in the Viscount Stansgate, has add the Duke trustees, Dr. -

Dossier De Presse Nomination Bartoli EN

New director for Monte-Carlo Opera appointed Cecilia Bartoli to take over from Jean-Louis Grinda on 1 January 2023 At a press conference in Salle Garnier on Tuesday 3 December, H.R.H. the Princess of Hanover, Chair of the Monte-Carlo Opera Board of Directors, made an important announcement: Cecilia Bartoli will take over from Jean-Louis Grinda as director of the Monegasque institution on 1 January 2023. “In March 2019, Jean-Louis Grinda informed Me and H.S.H. the Sovereign Prince of his intention to eventually leave his post as director of the Monte-Carlo Opera. Having occupied this position since July 2007, he felt that, in all good conscience, the time had come to hand over to someone who would bring new ideas to opera in the Principality. Jean-Louis Grinda then mentioned the name of Cecilia Bartoli, whom he had informally consulted. In addition to her personal and professional qualities, Cecilia already has strong ties to the Principality, having led the Musicians of the Prince as artistic director since the ensemble was established in 2016. This attractive proposition naturally caught my interest and attention as Chair of the Opera’s Board of Directors. After receiving the agreement of H.S.H. the Sovereign Prince, a proposal was officially made to Cecilia Bartoli which, I am delighted to say, she accepted,” said Her Royal Highness. Cecilia Bartoli will thus become the first woman to lead the Monte-Carlo Opera. She will also stay on as director of the Musicians of the Prince. “Cecilia Bartoli will, of course, be free to pursue her exceptional career as a singer, just as Jean-Louis Grinda has been free to work as a stage director,” concluded the Chair of the Board of Directors. -

6.5 X 11.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-45613-5 - The Cambridge Companion to Handel Edited by Donald Burrows Index More information Index Abraham, Gerald, 126–7, 308, 310 Armenia, 260 Abell, John, 87 Arne, Susanna, see Cibber, Susanna Abingdon (Oxfordshire), 255 Arne, Thomas Augustine, 69, 73, 75, 91, 153, Dall’Abaco, Giuseppe, 80 296 Academy of Vocal [Ancient] Music, 70–1, 152 Arsinoe, see Clayton Accademia della Crusca, 27 Atterbury Plot, 97, 175 Accademia Filarmonica (Bologna, Verona), 32 Augsburg, 39, 320 Accademia della Morte (Ferrara), 32 August, Duke of Saxony, 12–13, 15–16 Accademia dello Spirito Santo (Ferrara), 32 Augusta, Princess of Saxe-Gotha, Princess of Ackermann, Rudolph, 268 Wales, 178 Act of Settlement, 46 Austria, Emperor of, see Leopold I Adlington Hall, Cheshire, 217 Austrian Succession, War of the, 179–80 Addison, John, 52, 85, 90 Avelloni, Casimiro Aix-la-Chapelle, 178 Aix-la-Chapelle, Treaty/Peace of, 180 Babell, William, 69 d’Alay, Mauro, 80 Bach, J. S., 172, 195, 208, 218 Alberti, Johann Friedrich, 21, 210 Baker, Janet, 327 Albinoni, Tomaso, 38–9, 197–8 Banister, John, 68, 193 Aldrovandini, Giuseppe, 38 Barberini, Signora [Campanini, Barbarina], 85 Alexander the Great, 155–6 Barbier, Jane, 76 Alexander VIII, Pope (Ottoboni), 28 Baretti, Julia, 88 Amadei, Filippo, 80, 242 Barn-Elms [Barnes], Surrey, 66 Amiconi, Jacopo, 86 Barsanti, Francesco, 80–1 Amsterdam, 24, 39, 214, 217 Bartolotti, Girolamo, 80 Ancona, 26 Basel, 40 Andrews, Mr, 66 Baselt, Bernd, 22, 316 Angelini, Antonio Giuseppe, 41, 310 Bath, 84 Anne, Queen