After-School Mentorship Program and Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Middle-School Students Atia D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

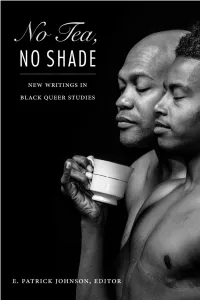

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Weirdo Canyon Dispatch 2018

Review: Roadburn Thursday 19th April 2017 By Sander van den Driesche It’s that time of the year again, the After Yellow Eyes it’s straight to the much anticipated annual pilgrimage to Main Stage to see Dark Buddha Rising Tilburg to join with many hundreds of perform with Oranssi Pazuzu as the travellers for Walter’s party at Waste of Space Orchestra, which is Roadburn. As I get off the train the another highly anticipated show, and in heat kicks me right in the face, what a this case one that won’t be played massive difference to the dull and rainy anywhere else (as far as I know). What morning I left behind in Scotland. This happened on that big stage was is glorious weather for a Roadburn phenomenal, we witnessed a near hour Festival! Bring it on! of glorious drone-infused psychedelic proggy doom. In fact, it felt a bit too early for me personally in the timing of the festival to experience such an extraordinarily mind-blowing set, but it was a remarkable collaboration and performance. I can’t wait for the Live at Roadburn release to come out (someone make it happen please!). Yellow Eyes by Niels Vinck After getting my bearings with the new venues, I enter Het Patronaat for the first of my highly anticipated performances of the festival, Yellow Eyes. But after three blistering minutes of ferocious black metal the PA system seems to disagree and we have our first “Zeal & Ardor moment” of 2018. It’s Waste of Space Orchestra by Niels Vinck not even remotely funny to see the On the same Main Stage, Earthless Roadburn crew frantically trying to played the first of their sets as figure out what went wrong, but luckily Roadburn’s artist in residence. -

New Releases & Discoveries 2017 (Click for PDF)

January 1, 2016 56 seasons by flyingdeadman (France) https://flyingdeadman.bandcamp.com/album/56-seasons-2 released January 5, 2017 When You're Young You're Invincible by Dayluta Means Kindness (El Paso, Texas) https://dayluta.bandcamp.com/album/when-youre-young-youre-invincible released January 6, 2017 Icarus by Sound Architects (Quezon City, Philippines) https://soundarchitects.bandcamp.com/track/icarus released January 6, 2017 0 by PHONOGRAPHIA (attenuation circuit - Augsburg, Germany) https://emerge.bandcamp.com/album/0-2 released January 1, 2017 Chill Kingdom by The American Dollar (New York) https://theamericandollar.bandcamp.com/track/chill-kingdom released January 1, 2017 Anticipation of an Uncertain Future by Various Artists (Preserved Sound - Hebden Bridge, UK) https://preservedsound.bandcamp.com/album/anticipation-of-an-uncertain-future released January 1, 2017 Swimming Through Dreams by Black Needle Noise with Mimi Page (Oslo, Norway) https://blackneedlenoise.bandcamp.com/track/swimming-through-dreams released January 1, 2017 The New Empire by cétieu (Warsaw, Poland) https://cetieu.bandcamp.com/album/the-new-empire released January 1, 2017 Live at the Smilin' Buddha Cabaret by Seven Nines & Tens (Vancouver) https://sevenninesandtens.bandcamp.com/album/live-at-the-smilin-buddha-cabaret released January 1, 2017 EUPANA @ VIVID POST-ROCK FESTIVAL-2016 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcX3VKgaVsE Published on 1 Jan 2017 Clones by Vacant Stations (UK) https://vacantstations.bandcamp.com/album/clones released January 1, 2017 Presence, -

Enthusiastic Cactus Promotes RHA at Stockton Get Involved Fair Artist

} “Remember, no one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” -Eleanor Roosevelt President Donald Trump’s First State of Union The Address Argo (gettyimages) The Independent Student Newspaper of Stockton University February 5, 2018 VOLUME 88 ISSUE 15 PAGE 7 Stockton in Manahawkin Opens Larger Site, Expands In This Issue Health Science Programs Diane D’Amico additional general education courses for the convenience FOR THE ARGO of students living in Ocean County. “I love it, said student Ann Smith, 21, of Ma- nahawkin, who along with classmates in the Accelerated BSN, or TRANSCEL program, used the site for the first time on Jan. 18. The Accelerated BSN students will spend one full (twitter) day a week in class at the site in addition to their clinical assignments and other classes. Former Stockton Employee is Art work from the Noyes Museum collection, in- Now Professional Wrester cluding some by Fred Noyes, is exhibited throughout the site, adding color and interest. PAGE 5 “It is much more spacious and very beautiful,” said student Christian Dy of Mullica Hill. The new site includes a lobby/lounge area with seating where students can eat lunch. There is a faculty lounge and small student hospitality area with snacks and (Photo courtesy of Stockton University) coffee. “They are here all day, and we want to them feel Students arriving for the spring semester at Stock- welcomed and comfortable,” said Michele Collins-Davies, ton University at Manahawkin discovered it had grown to the site manager. (liveforlivemusic) more than three times its size. “They did a really good job,” said student Lindsay The expansion into the adjacent 7,915 square-foot Carignan of Somers Point, who said her drive is a bit lon- LCD Soundsystem’s First building at 712 E. -

ED382869.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 382 869 CE 069 050 TITLE Occupational Literacy. A Training Profile Development Project for Ontario Basic Skills/Formation de base de l'Ontario. INSTITUTION Ontario Ministry of Skills Development, Toronto. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 361p. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; Adult Literacy; *Basic Skills; *Behavioral Objectives; *Communication Skills; Computer Literacy; Employer Attitudes; Foreign Countries; French; Job Skills; *Literacy Education; *Numeracy; Profiles; Science Process Skills; Vocational Adjustment IDENTIFIERS Ontario; *Workplace Literacy ABSTRACT This document resulted from a project undertaken to develop a set of program-specific and occupationally relevant performance (learning) obje :tives for the Ontario Basic Skills/Formation de Base de 1'Ontario (OBS/FBO) program. It describes project activities, including a literature review in three related areas: understanding what literacy means, occupational literacy research findings, and basic skills for the workplace. Two project stages are discussed. The first is a survey in English and French of 325 Ontario (Canada) employers in 9 industrial sectors. The survey identified the core basic skills required at three entry levels to employment. The second stage is the consolidation of the survey findings into preliminary performance objectives for each of the six subject areas in OBS/FBO: communications, numeracy, science, computer literacy, work adjustment, and technical hands-on. The terminal performance objectives are presented in the body of the report. Appendixes, amounting to over one-half of the report, include the following,: lists of employers surveyed; survey results; provincial, regional, and sectoral results; occupational sector job positions; onsite points of observation; OBS terminal and enabling objectives; and FBO terminal and enabling objectives. -

Journal of Agricultural Education 1 Volume 58, Issue 1, 2017

Journal of Agricultural Education 1 Volume 58, Issue 1, 2017 Journal of Agricultural Education A Publication of the American Association for Agricultural Education Volume 58, Issue 1, 2017 Editing Managing Board (Terms end on December 31) Member Region University Term Ends Ryan G. Anderson North Central Iowa State University 2019 Chris Estepp Southern Sul Ross State University 2018 Jeremy Falk Western University of Idaho 2017 Brad Greiman (Chair) North Central University of Minnesota 2017 Neil Knobloch North Central Purdue University 2018 Misty Lambert Western Oregon State University 2018 Dustin Perry Western Montana State University 2019 Chris Stripling Southern University of Tennessee 2019 Kirk Swortzel (Past Chair) Southern Mississippi State University 2017 Editorial Staff Harry N. Boone, Jr., Ph.D., Editor (2016-2018) Department of Agricultural and Extension Education, West Virginia University 4417 Agricultural Sciences Building, P.O. Box 6108 Morgantown, WV 26506 Phone: (304) 293-5451 Email: [email protected] D. Barry Croom, Past Editor, Oregon State University Tyson Sorensen, Utah State University, Assistant Editor Editorial Review Board (Terms end on December 31) Member Region University Term Ends Jessica Blythe North Central West Virginia University 2017 James Christiansen Western Texas A&M 2018 D. Barry Croom Western Oregon State University 2017 Catherine A. DiBenedetto Southern Clemson University 2018 John Ewing North Central Pennsylvania State University 2019 Jeremy Falk Western University of Idaho 2017 Jason McKibben -

Rethinking Post-Humanitarianism in the Context of Social Media Logic

Department of Informatics & Media Digital Media and Society Programme Humanitarianism on social media: Rethinking post-humanitarianism in the context of social media logic Master Thesis Presents: Gulizhaer Yahefu Supervisor: Jakob Svensson Uppsala University- August 2016 Abstract In this master thesis project, I attempt to explore the potential of social media in humanitarian communication. One of the major contributions in recent humanitarian communication studies is Chouliaraki’s theorization of post-humanitarianism, which is technologization of action and de-emotionalization of the causes. However, no studies have taken logic of social media into consideration yet. Therefore, I decided to take social media logic, which are programmability, connectivity and popularity, as one of the theoretical frameworks to explore how it influences dynamics of humanitarian communication. At the same time, I aspire to investigate whether the humanitarian communication on social media fulfill any characteristics of post-humanitarianism. Through conducting in-depth interviews with campaign organizer, campaign participant (volunteer) and random social media users, the result shows that the logic of social media has certain impact on the outcome of humanitarian campaigns, for instance, programmability enables them to actively create their own content, especially they are able to post direct contents from the field, which could potentially build trust between audience and humanitarian practitioners. However, the study also shows that humanitarian communication on social media does show some characteristics of post-humanitarianism, such as compassion fatigue, because the large public seem to be reluctant to act due to the proliferation of similar humanitarian appeals. However, connectivity could change their view if their significant others share, like or comment on a campaign. -

Newvmusic Zine Issue 2

New V Music The Zine Volume. 2 June 25th , 2021 CCDE Takeover F.O.E. EP Review LGBTQ+ Playlist Summer Jams Juneteenth Unshelved #TAGGEDURIT Index: Credits & Special Page 3………… Credits Thanks Page 4……… Songs of the Summer Pages 6-13 ………CCDE Writers & Contributors: Angela Vance Takeover Gillian Brigance David Higgins Pages 16-17 ……… LGBTQ+ Joesph Higgins Lillian McConnell Thru The Decades Playlist Vivian ‘Twiggy’ Vance Publishing: Page 18……… EP Review: Gillian Brigance ʻT.I.M.E F.O.R. I.Tʼ F.O.E Production: Angela Vance Page 19………… Song Review Special Thanks and Acknowledgements to: ʻBop-Onʼ 1100 G-Way David Higgins, Joseph Higgins, Chinese Connection Dub Embassy, Negro Terror, DJ Paul, Frederick “Foe” Field IV, Nichole Morris, Pages 20-21……The Shelving Patrick Houston, Sir Elton John (for being of Juneteenth fabulous), Mid South Pride, Opal Lee, & Fox 4 KDFW Fort Worth Page 22 ……… #taggedurit Friends Chase Atlantic Songs of the This one came out in 2015, but thanks to TikTok it has gained popularity. The vocals are smooth and the flow is comfortable if that makes sense. You can picture yourself driving down the highway with this one on loud and nothing planned. We like it because it makes us feel good to see a story about success after years of hard work and patience finally paying off. Who doesn’t Summer want to believe the universe rewards us for being patient and never giving up? Favorite Crime Olivia Rodrigro Who doesn’t like Olivia Rodrigo right now? She seems to be the “it” artist, but this song we had to add for it’s actual value as a gift to the summer playlist. -

18-02 Newsflash

DRONE RECORDS ҉ NEWSFLASH ҉ FEBRUARY 2018 ҉ Dear Droners and Psychonauts, here is the NEWSFLASH for February 2018 ! [#1 this year] as usual SOME PERSONAL RECOMMENDATIONS of NEW releases first (stuff that endlessly drones in our heads & hearts) : DEISON / MINGLE - Innersurface CD St.An.Da. 1701 ROBERT CURGENVEN - Climata do-CD Dragon's Eye Recordings der012 / Recorded Field Editions rfe_03 2016 KASSEL JAEGER - Aster do-LP Editions Mego EMEGO 235 MYTRIP - Circle of Loss MC AMEK amek020 LIFE GARDEN - The Living Room Tapes MC Dawn Ride DR-1 EYVIND KANG - Plainlight LP Abduction ABDT060 RAISON D'ETRE - Alchymeia CD Cyclic Law 101st Cycle AUME - Elemental CD + DVD Mobilization Records 2017 Pre-orders & reservations are possible. Please note the PRICES with your order! Most of the titles listed are in stock, others are backorderable quickly. All prices are in EURO and do NOT include postage & handling costs! Usually the minimum order amount is 25 Euro. The FULL mailorder-backprogramme is viewable (with search- & orderfunction) on our website www.dronerecords.de . Please send your orders & all communication to: [email protected] BEST DRONES !! Le BaraQue LABEL & CAT- NR. TITLE FORMAT YEAR? SHORT INFO / EDITION / LIM.?/ SPECIALS PRICE MORE INFO WWW NR first vinyl re-issue of this not very well known album from 2001 (CD ADAMSON, BARRY + PAN on Kitchen Motors), the amazing collaboration of PAN SONIC with Cold Spring Records 1 SONIC + HAFLER TRIO - The LP 2017 BARRY ADAMSON (MAGAZINE, NICK CAVE & THE BAD SEEDS), €18,00 www.coldspring.co.uk CSR241LP Hymn of the 7th Illusion and a fabulous 23 min. remix by HAFLER TRIO, which is alone worth the money new dark ambient project consisting of PAR BOSTROM (KAMMARHEIT) and "magic plants & alchemy" specialist KENNETH HANSSON, subtle, dense, and ghostly drones...; "ALTARMANG 2 ALTARMANG - Void CD Cyclic Law CL 99 2017 offers uniquely intuitive and hypnotic atmospherics through reel-to- €13,00 cycliclaw.bandcamp.com/album/void reel tape loops and analog tonalities. -

Analysis and Decision-Making with Social Media

Analysis and Decision-Making with Social Media by Lydia Manikonda A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved May 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Subbarao Kambhampati, Chair Huan Liu Baoxin Li Munmun De Choudhury Ece Kamar ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY August 2019 ABSTRACT The rapid advancements of technology have greatly extended the ubiquitous nature of smart- phones acting as a gateway to numerous social media applications. This brings an immense con- venience to the users of these applications wishing to stay connected to other individuals through sharing their statuses, posting their opinions, experiences, suggestions, etc on online social networks (OSNs). Exploring and analyzing this data has a great potential to enable deep and fine-grained insights into the behavior, emotions, and language of individuals in a society. This proposed disser- tation focuses on utilizing these online social footprints to research two main threads – 1) Analysis: to study the behavior of individuals online (content analysis) and 2) Synthesis: to build models that influence the behavior of individuals offline (incomplete action models for decision-making). A large percentage of posts shared online are in an unrestricted natural language format that is meant for human consumption. One of the demanding problems in this context is to leverage and develop approaches to automatically extract important insights from this incessant massive data pool. Efforts in this direction emphasize mining or extracting the wealth of latent information in the data from multiple OSNs independently. The first thread of this dissertation focuses on analytics to investigate the differentiated content-sharing behavior of individuals. -

The Impact of a Rap Writing Music Therapy Intervention on Self-Esteem

We're Free: The Impact of a Rap Writing Music Therapy Intervention on Self-Esteem of At-Risk Adolescents in a Public Middle School Setting A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Music Jessica L. Schlabach May 2015 © 2015 Jessica L. Schlabach. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled We're Free: The Impact of a Rap Writing Music Therapy Intervention on Self-Esteem of At-Risk Adolescents in a Public Middle School Setting by JESSICA L. SCHLABACH has been approved for the School of Music and the College of Fine Arts by Kamile Geist Associate Professor of Music Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT SCHLABACH, JESSICA L., M.M., May 2015, Music Therapy We're Free: The Impact of a Rap Writing Music Therapy Intervention on Self-Esteem of At-Risk Adolescents in a Public Middle School Setting Director of Thesis: Kamile Geist The negative behaviors displayed by adolescents who are at-risk can have detrimental effects on society. Developmentally appropriate, engaging treatments that adolescents enjoy may be the most successful as preventative interventions. The purpose of this study was to investigate rap writing as a possible treatment intervention to improve self-esteem of at-risk adolescents. A convergent, mixed methods design was used to provide qualitative insight into quantitative results. Quantitative measures include the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and a frequency count of low self-esteem behaviors. Qualitative measures included a thematic analysis of a post study questionnaire, a session transcription, and lyrics written by the participants. -

IMOJP17 528 Songs, 1.6 Days, 9.15 GB

Page 1 of 21 IMOJP17 528 songs, 1.6 days, 9.15 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 What Do I Do 7:48 Thawing Dawn A. Savage 2 One Thing at a Time 3:56 HaHa HuHu Aaron Roche @AaronRoche 3 Like Why I 6:56 HaHa HuHu Aaron Roche @AaronRoche 4 K Is Manic 1:31 HaHa HuHu Aaron Roche @AaronRoche 5 Failure In Chrome 7:10 AZD Actress 6 SLEEPlessinIndonesia 21:47 agf 7 1_AGF_theSELF 4:27 the self / the other AGF @poemproducer 8 Takamba (Gulls DUB) 5:07 FAMILY ALBUM 2017 Aghali Ag Amoumine @ag_amoumine 9 Each Other 4:12 Each Other Aidan Knight 10 My Brain is a Human Body 2:14 The Bible 2 AJJ 11 Darkness at Noon 3:51 You & I ALA.NI 12 Sagrado Corazon de Jesu Second Attempt 13:27 Solo Guitar Alan Sparhawk 13 How the Weather Hits the Freighter 1:52 Solo Guitar Alan Sparhawk 14 Horizon 4:10 Party Aldous Harding 15 Party 5:45 Party Aldous Harding 16 Swell Does The Skull 5:48 Party Aldous Harding 17 Ty 2:29 Arcadian Pages Alex Rose @alexrosebb 18 Tres Piezas - III. Danza Rustica 2:16 OFF THE EDGE Alicia Terzian 19 Start My Center 6:56 Start My Center American Anymen 20 Less Complex 4:45 Oui EP American Anymen + Lise 21 I'm Not A Loser 1:50 Big Attraction Amyl and the Sniffers 22 Stole My Push Bike 1:00 Giddy Up Amyl and the Sniffers 23 Iso 5:58 Ore Andrea Belfi @AndreaBelfi IMOJP17 Page 2 of 21 Name Time Album Artist 24 Kiuá 5:51 Outro Tempo: Electronic And Contemporary Musi… Andréa Daltro 25 Animal 4:29 Realisationship Andrew Hung @ndrewhung 26 Unsetting Sun 3:39 Intent Andy The Doorbum & Justin Aswell 27 Equality & Death (mothers, fathers, where are Ye-) 7:38