Transformative Learning in College Students: a Mixed Methods Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

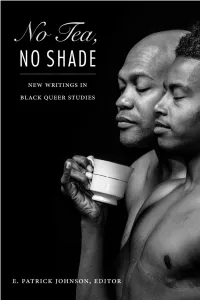

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Weirdo Canyon Dispatch 2018

Review: Roadburn Thursday 19th April 2017 By Sander van den Driesche It’s that time of the year again, the After Yellow Eyes it’s straight to the much anticipated annual pilgrimage to Main Stage to see Dark Buddha Rising Tilburg to join with many hundreds of perform with Oranssi Pazuzu as the travellers for Walter’s party at Waste of Space Orchestra, which is Roadburn. As I get off the train the another highly anticipated show, and in heat kicks me right in the face, what a this case one that won’t be played massive difference to the dull and rainy anywhere else (as far as I know). What morning I left behind in Scotland. This happened on that big stage was is glorious weather for a Roadburn phenomenal, we witnessed a near hour Festival! Bring it on! of glorious drone-infused psychedelic proggy doom. In fact, it felt a bit too early for me personally in the timing of the festival to experience such an extraordinarily mind-blowing set, but it was a remarkable collaboration and performance. I can’t wait for the Live at Roadburn release to come out (someone make it happen please!). Yellow Eyes by Niels Vinck After getting my bearings with the new venues, I enter Het Patronaat for the first of my highly anticipated performances of the festival, Yellow Eyes. But after three blistering minutes of ferocious black metal the PA system seems to disagree and we have our first “Zeal & Ardor moment” of 2018. It’s Waste of Space Orchestra by Niels Vinck not even remotely funny to see the On the same Main Stage, Earthless Roadburn crew frantically trying to played the first of their sets as figure out what went wrong, but luckily Roadburn’s artist in residence. -

Critical Reflection and Imaginative Engagement: Towards an Integrated Theory of Transformative Learning

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press 2018 Conference Proceedings (Victoria, BC Adult Education Research Conference Canada) Critical Reflection and Imaginative Engagement: Towards an Integrated Theory of Transformative Learning John M. Dirkx Michigan State University, [email protected] Benjamin D. Espinoza Michigan State University, [email protected] Steven Schlegel Michigan State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Dirkx, John M.; Espinoza, Benjamin D.; and Schlegel, Steven (2018). "Critical Reflection and Imaginative Engagement: Towards an Integrated Theory of Transformative Learning," Adult Education Research Conference. https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2018/papers/4 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adult Education Research Conference by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adult Education Research Conference 2018, University of Victoria, Canada, June 7-10 Critical Reflection and Imaginative Engagement: Towards an Integrated Theory of Transformative Learning John M. Dirkx, Benjamin D. Espinoza & Steven Schlegel Michigan State University Abstract: Based on a review of the literature, we propose an integrated approach to transformative learning grounded in a concept of multiple selves that recognizes the importance of both the rational and affective and the personal and the social dimensions in fostering self- understanding. Key words: transformative learning, affective experiences, self-understanding Introduction and Rationale Over 40 years ago, Jack Mezirow (1978) introduced the idea of transformative learning as a way to theoretically represent the relative uniqueness of learning in adulthood. -

New Releases & Discoveries 2017 (Click for PDF)

January 1, 2016 56 seasons by flyingdeadman (France) https://flyingdeadman.bandcamp.com/album/56-seasons-2 released January 5, 2017 When You're Young You're Invincible by Dayluta Means Kindness (El Paso, Texas) https://dayluta.bandcamp.com/album/when-youre-young-youre-invincible released January 6, 2017 Icarus by Sound Architects (Quezon City, Philippines) https://soundarchitects.bandcamp.com/track/icarus released January 6, 2017 0 by PHONOGRAPHIA (attenuation circuit - Augsburg, Germany) https://emerge.bandcamp.com/album/0-2 released January 1, 2017 Chill Kingdom by The American Dollar (New York) https://theamericandollar.bandcamp.com/track/chill-kingdom released January 1, 2017 Anticipation of an Uncertain Future by Various Artists (Preserved Sound - Hebden Bridge, UK) https://preservedsound.bandcamp.com/album/anticipation-of-an-uncertain-future released January 1, 2017 Swimming Through Dreams by Black Needle Noise with Mimi Page (Oslo, Norway) https://blackneedlenoise.bandcamp.com/track/swimming-through-dreams released January 1, 2017 The New Empire by cétieu (Warsaw, Poland) https://cetieu.bandcamp.com/album/the-new-empire released January 1, 2017 Live at the Smilin' Buddha Cabaret by Seven Nines & Tens (Vancouver) https://sevenninesandtens.bandcamp.com/album/live-at-the-smilin-buddha-cabaret released January 1, 2017 EUPANA @ VIVID POST-ROCK FESTIVAL-2016 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcX3VKgaVsE Published on 1 Jan 2017 Clones by Vacant Stations (UK) https://vacantstations.bandcamp.com/album/clones released January 1, 2017 Presence, -

After-School Mentorship Program and Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Middle-School Students Atia D

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2018 After-School Mentorship Program and Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Middle-School Students Atia D. Mark Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Education This is to certify that the doctoral study by Atia D. Mark has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Steve Wells, Committee Chairperson, Education Faculty Dr. Gloria Jacobs, Committee Member, Education Faculty Dr. Michael Brunn, University Reviewer, Education Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2018 Abstract After-School Mentorship Program and Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Middle-School Students by Atia D. Mark MA, Concordia University, 2012 BS, University of the West Indies, 2009 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education Walden University August 2018 Abstract Middle-school students in Nova Scotia are perceived to have low self-efficacy for achieving learning outcomes. Strong self-efficacy beliefs developed through effective curricula have been linked to improved academic performance. However, there is a need for the formal evaluation of effective curricula that aim to improve self-efficacy. -

Exploring the Impacts of a Short-Term International Teaching Practicum in Hong Kong

Up, up, and away: Exploring the impacts of a short-term international teaching practicum in Hong Kong by Natalie Chow Department of Integrated Studies in Education McGill University, Montréal June 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Natalie Chow, 2015 ii Abstract The option of teaching abroad in some teacher education programs encourages teacher candidates to enrich pedagogical strategies and increase cross-cultural sensitivity (Maynes, Allison, & Julien-Schultz, 2013). Despite these benefits, international practica today represent one of the least well-developed types of study abroad programs (Kissock & Richardson, 2010). This qualitative study investigated the experiences of eight Quebec teacher candidates specializing in Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL) who participated in an 8-week teaching practicum in Hong Kong. Transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1978) and situated learning perspectives (Conceição & Skibba, 2008; Cushner & Mahon, 2002; Lave & Wenger, 1991; McLellan, 1996;) were used as primary lenses to conceptualize and analyze data in order to illuminate the depth of individual experiences. Data collection methods included pre- and post-experience questionnaires, an online discussion forum, journal entries, and semi-structured interviews. Thematic analysis was used as the main form of data analysis. Students reported on various facets of teaching in Hong Kong as pivotal in their professional and personal development. The findings reveal that participating in an international practicum promotes ongoing reflection and transformative learning while boosting teacher confidence for educating learners in increasingly globalized classrooms. Recommendations for how teacher education programs might establish or further support international field experiences are provided. -

Enthusiastic Cactus Promotes RHA at Stockton Get Involved Fair Artist

} “Remember, no one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” -Eleanor Roosevelt President Donald Trump’s First State of Union The Address Argo (gettyimages) The Independent Student Newspaper of Stockton University February 5, 2018 VOLUME 88 ISSUE 15 PAGE 7 Stockton in Manahawkin Opens Larger Site, Expands In This Issue Health Science Programs Diane D’Amico additional general education courses for the convenience FOR THE ARGO of students living in Ocean County. “I love it, said student Ann Smith, 21, of Ma- nahawkin, who along with classmates in the Accelerated BSN, or TRANSCEL program, used the site for the first time on Jan. 18. The Accelerated BSN students will spend one full (twitter) day a week in class at the site in addition to their clinical assignments and other classes. Former Stockton Employee is Art work from the Noyes Museum collection, in- Now Professional Wrester cluding some by Fred Noyes, is exhibited throughout the site, adding color and interest. PAGE 5 “It is much more spacious and very beautiful,” said student Christian Dy of Mullica Hill. The new site includes a lobby/lounge area with seating where students can eat lunch. There is a faculty lounge and small student hospitality area with snacks and (Photo courtesy of Stockton University) coffee. “They are here all day, and we want to them feel Students arriving for the spring semester at Stock- welcomed and comfortable,” said Michele Collins-Davies, ton University at Manahawkin discovered it had grown to the site manager. (liveforlivemusic) more than three times its size. “They did a really good job,” said student Lindsay The expansion into the adjacent 7,915 square-foot Carignan of Somers Point, who said her drive is a bit lon- LCD Soundsystem’s First building at 712 E. -

Transformational Learning: an Investigation of the Emotional Maturation Advancement in Learners Aged 50 and Older Susan Lorraine Lundry University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 12-18-2015 Transformational Learning: An Investigation of the Emotional Maturation Advancement in Learners Aged 50 and Older Susan Lorraine Lundry University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Lundry, Susan Lorraine, "Transformational Learning: An Investigation of the Emotional Maturation Advancement in Learners Aged 50 and Older" (2015). Dissertations. 131. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/131 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSFORMATIONAL LEARNING: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE EMOTIONAL MATURATION ADVANCEMENT IN LEARNERS AGED 50 AND OLDER Susan L. Lundry A.A., St. Louis Community College, 2000 B.A., University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2002 M.Ed., University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2005 M.Ed., University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2013 Ed.S., University of Missouri-Columbia, 2015 A Dissertation Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri-St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education December 2015 Advisory Committee E. Paulette Isaac-Savage, Ed.D. Chairperson Kathleen M. Haywood, Ph.D. Paul J. Wilmarth, Ph.D. John A. Henschke, Ed.D. Transformational Learning ii Abstract Human beings have spent much time and effort in trying to understand themselves, others, and their world. Mankind uses intellect when trying to understand life but the majority of people continue to encounter frustration, confusion, and a variety of obstacles when dealing with daily challenges and people. -

Transformative Learning Through Mindfulness: Exploring the Mechanism of Change Thomas Howard Morris

Australian Journal of Adult Learning Volume 60, Number 1, April 2020 Transformative learning through mindfulness: Exploring the mechanism of change Thomas Howard Morris School of Education, Bath Spa University Making appropriate perspective transformations as we age is necessary to meet the demands of the rapidly changing conditions within our world. Accordingly, there has been a growing interest in the role of mindfulness in enabling transformations. Still, how mindfulness may facilitate perspective transformations is not well understood. The present paper draws from empirical evidence from psychology and cognitive science to discuss the theoretical possibility that mindfulness may facilitate perspective transformations. A theoretical model is presented that depicts an incremental transformative learning process that is facilitated through mindfulness. Mindfulness affords the adult enhanced attention to their thoughts, feelings, and sensations as they arise in the present moment experience. This metacognitive awareness may moderate the expression of motivational disposition for the present moment behaviour, enabling a more objective assessment of the conditions of the situation. Nonetheless, in accordance with transformative learning theory, an adult would have to become critically aware of and analyse the assumptions that underlie the reasons why they experience as they do in order to convert behaviour change to perspective transformation. Further empirical studies are Transformative learning through mindfulness: Exploring the mechanism of change 45 necessary to test this assumption of the theoretical model presented in the present paper. Keywords: Adult learning, Jack Mezirow, transformative learning theory, mindfulness, perspective transformation, lifelong learning Introduction Understanding how to realise the potential of humans and our sustainable development consists of considering human development from diverse perspectives (Cunningham, 2019; Duke, 2018). -

In Pursuit of Transformative Learning: Exploring the Stimulation of Curiosity Through Critical Reflection in the College Classroom

University of San Diego Digital USD Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2018-05-20 In Pursuit of Transformative Learning: Exploring the Stimulation of Curiosity Through Critical Reflection in the College Classroom Bo Y. Bae University of San Diego Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/dissertations Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Commons, Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Leadership Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, Higher Education and Teaching Commons, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons Digital USD Citation Bae, Bo Y., "In Pursuit of Transformative Learning: Exploring the Stimulation of Curiosity Through Critical Reflection in the College Classroom" (2018). Dissertations. 106. https://digital.sandiego.edu/dissertations/106 This Dissertation: Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN PURSUIT OF TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING: EXPLORING THE STIMULATION OF CURIOSITY THROUGH CRITICAL REFLECTION IN THE COLLEGE CLASSROOM by Bo Bae A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 Dissertation Committee Cheryl Getz, EdD Robert Donmoyer, PhD Marcus -

Theories of Learning

Theories of Learning SAGE Library of Educational Thought & Practice Edited by David Scott Institute of Education Four-Volume Set In recent years, research into learning has become increasingly important as a significant academic pursuit. Bringing together a wide range of articles, written by internationally renowned scholars, this four-volume collection provides an overview of the many theories of learning, from Aristotle to Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Michel Foucault. Editor David Scott, in an extensive introduction, presents a comprehensive account of the subject, which ranges from philosophical, sociological and psychological perspectives on learning and models of learning, to those important relations between learning, curriculum, pedagogy and assessment, and finally concludes with ideas and themes related to learning dispositions, life-long learning and learning environments. The whole work consists of 80 articles (including the introduction) organized into four volumes: Volume One: Philosophical, Sociological and Psychological Theories of Learning Volume Two: Models of Learning Volume Three: Learning, Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment Volume Four: Learning Dispositions, Lifelong Learning and Learning Environments October 2012 • 1600 pages Cloth (978-1-4462-0907-3) Price £600.00 Special Introductory Offer • £550.00 (on print orders received before the end of month of publication) Contents VOLUME ONE: PHILOSOPHICAL, 16. Where Is the Mind? 30. Vygotsky, Tutoring SOCIOLOGICAL AND Constructivist and and Learning PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORIES Sociocultural Perspectives on David Wood and OF LEARNING Mathematical Development Heather Wood Paul Cobb 31. Aporias Webs and 1. Intellectual Evolution from 17. Multiple Intelligences Go Passages: Doubt as an Adolescence to Adulthood to School: Educational Opportunity to Learn Jean Piaget Implications of the Theory Nicholas Burbules, 2. -

Narrative Theories and Learning in Contemporary Art Museums: a Theoretical Exploration

Narrative Theories and Learning in Contemporary Art Museums: A Theoretical Exploration Dr. Emilie Sitzia Stories are an integral part of our experience as human beings. As Roland Barthes put forward, narrative “is present at all times, in all places, in all societies; indeed narrative starts with the very history of mankind; there is not, there has never been anywhere, any people without narratives; all classes, all human groups have their stories….”1 Narrative theories (in literature, media studies, psychology, or neurology) have explored the impacts of narratives on our ways of being, thinking, dreaming, and remembering. This article will explore the implications of narrative theories for learning in a contemporary art museum context. The different discourses of the museum, the way narratives are constructed in museum spaces, and how museum spaces can be considered syntactical have been explored by scholars such as Mieke Bal, Bruce W. Ferguson, and Tony Bennett.2 This article proposes to build on this existing literature as well as other areas of narrative theory to investigate beyond the discursive system of the museum display and its narrative qualities, in order to focus on the impact of these narratives on learning processes.3 The art museum, and the contemporary art museum in particular, implies a certain frame for the visitor and a certain set of expectations: an openness of interpretation, a type of experience, a kind of authorial voice, etc. As Ferguson argues, in art exhibitions “the idea that meanings are impossibly unstable is embraceable because inevitable. With works of art, meanings are only produced in context and that is a collective, negotiated, debated and shifting consensual process of determination.