The Dendroclimatological Potential of Willamette Valley Quercus Garryana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West-Side Prairies & Woodlands

Washington State Natural Regions Beyond the Treeline: Beyond the Forested Ecosystems: Prairies, Alpine & Drylands WA Dept. of Natural Resources 1998 West-side Prairies & Woodlands Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems West-side Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems in Grey San Juan Island Prairies 1. South Puget Sound prairies & oak woodlands 2. Island / Peninsula coastal prairies & woodlands Olympic Peninsula 3. Rocky balds Prairies South Puget Prairies WA GAP Analysis project 1996 Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems San Juan West-side Island South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Oak Woodland & Prairie Prairies Ecosystems in Grey Grasslands dominated by Olympic • Grasses Peninsula Herbs Prairies • • Bracken fern South • Mosses & lichens Puget Prairies With scattered shrubs Camas (Camassia quamash) WA GAP Analysis project 1996 •1 South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Mounded prairie Some of these are “mounded” prairies Mima Mounds Research Natural Area South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Scattered shrubs Lichen mats in the prairie Serviceberry Cascara South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems As unique ecosystems they provide habitat for unique plants As unique ecosystems they provide habitat for unique critters Camas (Camassia quamash) Mazama Pocket Gopher Golden paintbrush Many unique species of butterflies (Castilleja levisecta) (this is an Anise Swallowtail) Photos from Dunn & Ewing (1997) •2 South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Fire is -

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

Oaks for Nebraska Justin R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications Nebraska Statewide Arboretum 2013 Oaks for Nebraska Justin R. Evertson University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arboretumpubs Part of the Botany Commons, and the Forest Biology Commons Evertson, Justin R., "Oaks for Nebraska" (2013). Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications. 1. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arboretumpubs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Statewide Arboretum at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Oaks for Nebraska Justin Evertson, Nebraska Statewide Arboretum arboretum.unl.edu or retreenebraska.unl.edu R = belongs to red oak group—acorns mature over two seasons & leaves typically have pointed lobes. W = belongs to white oak group— acorns mature in one season & leaves typically have rounded lobes. Estimated size range is height x spread for trees growing in eastern Nebraska. A few places to see oaks: Indian Dwarf chinkapin oak, Quercus Cave State Park; Krumme Arboretum Blackjack oak, Quercus prinoides (W) in Falls City; Peru State College; marilandica (R) Variable habit from shrubby to Fontenelle Nature Center in Bellevue; Shorter and slower growing than tree form; prolific acorn producer; Elmwood Park in Omaha; Wayne most oaks with distinctive tri- can have nice yellow fall color; Park in Waverly; University of lobed leaves; can take on a very national champion grows near Nebraska Lincoln; Lincoln Regional natural look with age; tough and Salem Nebraska; 10-25’x 10-20’. -

Bur Oak Quercus Macrocarpa Tree Bark ILLINOIS RANGE

bur oak Quercus macrocarpa Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division: Magnoliophyta The deciduous bur oak tree may grow to 120 feet Class: Magnolioposida tall with a trunk diameter of five feet. Its bark is dark Order: Fagales brown or yellow-brown with deep furrows. The bud is rounded or slightly pointed at the tip, yellow- Family: Fagaceae brown to red-brown and hairy. The simple leaves are ILLINOIS STATUS arranged alternately along the stem. The leaf blade is broad at the upper end and coarsely round- common, native toothed. The leaf has five to seven lobes. Each leaf is © Guy Sternberg dark green and smooth or slightly hairy on the upper surface and pale and hairy on the lower surface. The leaf may be 14 inches long and seven inches wide with a one inch leaf stalk. Male and female flowers are separate but located on the same tree. Neither type of flower has petals. Male (staminate) flowers are arranged in drooping catkins, while the female (pistillate) flowers are clustered in a small group. The fruit is a solitary acorn. The dark brown acorn may be ovoid to ellipsoid and up to one and three- quarter inches long. The hairy cup covers half to nearly all of the nut and has a fringe of long scales. BEHAVIORS The bur oak may be found statewide in Illinois. This tree tree grows almost anywhere, from dry ridges to bottomland woods. The bur oak flowers in April and May, about the time that its leaves begin to unfold. ILLINOIS RANGE Its heavy, hard wood is used in making cabinets, for ship building, for fence posts and for fuel. -

A Trip to Study Oaks and Conifers in a Californian Landscape with the International Oak Society

A Trip to Study Oaks and Conifers in a Californian Landscape with the International Oak Society Harry Baldwin and Thomas Fry - 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Aims and Objectives: .................................................................................................................................................. 4 How to achieve set objectives: ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Sharing knowledge of experience gained: ....................................................................................................................... 4 Map of Places Visited: ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Itinerary .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Background to Oaks .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Cosumnes River Preserve ........................................................................................................................................ -

Planting Native Oak in the Pacific Northwest. Gen

United States Department of Agriculture Planting Native Oak Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest Pacific Northwest Research Station Warren D. Devine and Constance A. Harrington General Technical Report PNW-GTR-804 February 2010 D E E P R A U R T LT MENT OF AGRICU The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and National Grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Pesticide Precautionary Statement This publication reports research involving pesticides. -

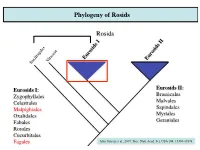

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

Heritage Trees of Portland

Heritage Trees of Portland OREGON WHITE OAK (Quercus garryana) FAGACEAE z Native from southern B.C. to central California. z Height can be greater than 150'. z Leaves very dark green, leathery, 5-7 rounded lobes; brown leaves remain well into winter. z Acorns 1" long, ovoid, cup is shallow. z Somewhat common in Portland; a few 150-200 yr olds saved from development. #19 is perhaps the largest in the city. #179 was saved from developer’s ax in 1998. 4 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 2137 SE 32nd Pl* H 40, S 80, C 14.7 8 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 7168 N. Olin H 80, S 96, C 15.17 10 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) NW 23rd & Overton* H 80, S 86, C 14.33 19 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 1815 N. Humboldt* H 80, S 97, C 20.08 21 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 1224 SE Sellwood* H 65, S 78, C 15.83 23 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 825 SE Miller* H 80, S 75, C 15.33 27 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 5000 N. Willamette Blvd*, University of Portland H 50, S 90, C 13.75 71 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 9107 N. Richmond* H 80, S 75, C 15.5 75 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 4620 SW 29th Pl* H 60, S 100, C 16 141 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 4825 SW Dosch Park Ln* 142 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 4825 SW Dosch Park Ln* H 73-120, S 64-100, C 12-12.4 143 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 4825 SW Dosch Park Ln* 157 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) SW Patton Rd, Portland Heights Park H 87, S 94, C 17 171 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) SW Macadam & Nevada, Willamette Park H 102, S 72, C 17 179 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) SW Corbett & Lane, Corbett Oak Park H 73, S 73, C 13.3 198 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 199 200 7654 N. -

Blue Oak Plant Communities of Southern

~ United States ~ Department Blue Oak Plant Communities of Southern of Agriculture Forest Service San Luis Obispo and Northern Santa Bar Pacific Southwest Research Station bara Counties, California General Technical Report PSW-GTR-139 Mark I. Borchert Nancy D.Cunha Patricia C. Kresse Marcee L. Lawrence Borchert. M:1rk I.: Cunha. N,mcy 0.: Km~,e. Patr1c1a C.: Lawrence. Marcec L. 1993. Blue oak plan! communilies or:.outhern San Luis Ob L<ipo and northern Santa Barbara Counties, California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-139. Albany. CA: P:u:ilic Southwest Rcsc:arch Stution. Forest Service. U.S. Dcpurtment of Agriculture: 49 p. An ccologic:11clu,-sili.::uion '),,cm h:b Ileen developed for the Pacifil' Southwest Region of the Forest Service. As part of that c1a....,11ica1ion effort. blue oak rQ11('rrn., tlo11i;lusi1 / woodlands and forests ol ~out hem San Lub Ohi,po and northern Santa Barham Countie, in LO!> Padre!> Nationul Forest were cl:",ilicd imo i.\ plant communitic, using vegetation colkctcd from 208 plot:.. 0. 1 acre e:ach . Tim.'<.' di,tinct region, of vegetation were 1dentilicd 111 the ,tudy :1rea: Avcn:1lc,. Mirnndn Pinc Moun11,ln :ind Branch Mountnin. Communitie.., were dassilied ,eparntel) for plot, in each region. Each region ha, n woodland community thut occupies 11:u orgently slopmg bcnt·he..,.1oc,lopc~. and valley bo110111s. Thc,:c rnmmunitics possess a reltuivcly high proportion oflarge trcc, ( 2: I!( an. d.b.h.l 311d appcarro be heavily gnu cd. In s•ach region an extensive woodland or fore,t communit) covers modcr:uc , lope, with low ,olar in,ol:11io11 . -

Acorn Planting

Oak Harbor Garry Oak (Quercus garryana) Acorn Planting 10/09/14 by Brad Gluth Acorn Acquisition 1) Garry oak acorns have to be collected and planted in the Autumn that they are shed from the trees unless stored in refrigeration. 2) Gather acorns from beneath local trees only. Oaks hybridize easily and we are trying to preserve the genetics of the local trees. Acorn Selection 3) Float test the acorns. Place the acorns in a container of water. Remove and discard those that float. This is a density test and the floating acorns have been compromised through pests or other causes. Select the largest acorns from those that sank for planting. The larger acorns have more vigorous seedling growth. 4) Do not allow the acorns to dry out. It is best to not store them indoors. Planting Containers 5) Pots should be a minimum of 10” deep with drain holes. (Garry oaks quickly develop a deep tap root of up to 10” in the first season.) Soil Mix 6) The soil mix should be a well-draining mix. Sand mixed with potting soil works well. Planting 7) Soak acorns in water for 5 to 10 minutes prior to planting. 8) Plant 2-3 of the largest acorns on their side in each pot. Cover each acorn with about 1/4” of soil. (If more than one acorn germinates, the seedlings can be thinned, or separated from the pots for replanting.) 9) After planting, 1” of mulch should be placed on top of the soil. If available, oak leaf mulch is recommended. -

Soil Characteristics of Blue Oak and Coast Live Oak Ecosystems1

Soil Characteristics of Blue Oak and Coast Live Oak Ecosystems1 Denise E. Downie2 Ronald D. Taskey2 Abstract: In northern San Luis Obispo County, California, soils associated with blue oaks (Quercus douglasii) are slightly more acidic, have finer textures, stronger argillic horizons, and sometimes higher gravimetric water content at -1,500 kPa than soils associated with coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia). Soils associated with coast live oaks generally are richer in organic matter than those associated with blue oaks. Blue oaks seem to grow more frequently on erosional surfaces and in soils that sometimes have a paralithic contact at about 1 m depth, whereas coast live oaks may be found more frequently on depositional surfaces. Although the two species sometimes occupy seemingly comparable sites, results point to significant microsite differences between them. Full, conclusive characterizations useful in managing and enhancing oak woodlands will require study of many more sites. he distribution and productivity of California’s 3 million hectares of oak Twoodlands are controlled in part by the soils of these ecosystems; moreover, proficient management of oak woodlands requires ample knowledge of one of the most important, but least understood, habitat components—the soil. Blue oak (Quercus douglasii Hook. & Arn.) and coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia Née) are two important species in the central coast region that commonly grow in proximity, including in mixed stands. Nonetheless, the two species may have different site preferences, suggesting that different approaches to stand evaluation and management may be appropriate. An important step in determining site preferences is to adequately characterize the soils of these ecosystems. -

Quercus Garryana Pacific University Oregon White Oak Rehabilitation Case Study Jared Kawatani, ‘17 Center for a Sustainable Society, Pacific University

Quercus garryana Pacific University Oregon White Oak Rehabilitation Case Study Jared Kawatani, ‘17 Center for a Sustainable Society, Pacific University Introduction Quercus garryana can be found in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. Some of its common names are: Gary Oak, Oregon White Oak, and Oregon Oak. They are large slow growing hardwood trees that grow in woodlands, savannahs, and prairies. They are very versatile trees as they can grown in cool climates, humid coastal climates to hot, dry inland environments. But they prefer moist, fertile sites over the very dry conditions that they can grow in as well. Unfortunately, there are multiple problems that Oregon white oaks face over all as a species on the west coast. One of those issues is that they are threatened by the encroachment of other trees because they are sun loving and have a low tolerance for shade and thus get outcompeted. Historical records show this encroachment originally started to occur due to a loss of forest fire management done by the Native Americans in the area. These fires played a part in preventing the woodlands, savannahs, and prairies from being encroached on by the surrounding forests, and prevent bugs from eating the acorns that the Native Americans preferring to eat. The oaks have adapted to the environment that the Native Americans had created. Not only are they being out competed by the Douglas firs, their habitats are being lost to development. Oregon white oaks are also threatened by sudden oak death by the plant pathogen Phytophthora ramorum that was found in the south range of the trees (California and southern Oregon).