Planting Native Oak in the Pacific Northwest. Gen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West-Side Prairies & Woodlands

Washington State Natural Regions Beyond the Treeline: Beyond the Forested Ecosystems: Prairies, Alpine & Drylands WA Dept. of Natural Resources 1998 West-side Prairies & Woodlands Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems West-side Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems in Grey San Juan Island Prairies 1. South Puget Sound prairies & oak woodlands 2. Island / Peninsula coastal prairies & woodlands Olympic Peninsula 3. Rocky balds Prairies South Puget Prairies WA GAP Analysis project 1996 Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems San Juan West-side Island South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Oak Woodland & Prairie Prairies Ecosystems in Grey Grasslands dominated by Olympic • Grasses Peninsula Herbs Prairies • • Bracken fern South • Mosses & lichens Puget Prairies With scattered shrubs Camas (Camassia quamash) WA GAP Analysis project 1996 •1 South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Mounded prairie Some of these are “mounded” prairies Mima Mounds Research Natural Area South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Scattered shrubs Lichen mats in the prairie Serviceberry Cascara South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems As unique ecosystems they provide habitat for unique plants As unique ecosystems they provide habitat for unique critters Camas (Camassia quamash) Mazama Pocket Gopher Golden paintbrush Many unique species of butterflies (Castilleja levisecta) (this is an Anise Swallowtail) Photos from Dunn & Ewing (1997) •2 South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Fire is -

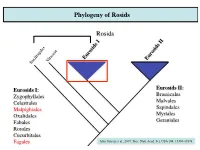

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

Heritage Trees of Portland

Heritage Trees of Portland OREGON WHITE OAK (Quercus garryana) FAGACEAE z Native from southern B.C. to central California. z Height can be greater than 150'. z Leaves very dark green, leathery, 5-7 rounded lobes; brown leaves remain well into winter. z Acorns 1" long, ovoid, cup is shallow. z Somewhat common in Portland; a few 150-200 yr olds saved from development. #19 is perhaps the largest in the city. #179 was saved from developer’s ax in 1998. 4 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 2137 SE 32nd Pl* H 40, S 80, C 14.7 8 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 7168 N. Olin H 80, S 96, C 15.17 10 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) NW 23rd & Overton* H 80, S 86, C 14.33 19 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 1815 N. Humboldt* H 80, S 97, C 20.08 21 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 1224 SE Sellwood* H 65, S 78, C 15.83 23 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 825 SE Miller* H 80, S 75, C 15.33 27 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 5000 N. Willamette Blvd*, University of Portland H 50, S 90, C 13.75 71 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 9107 N. Richmond* H 80, S 75, C 15.5 75 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 4620 SW 29th Pl* H 60, S 100, C 16 141 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 4825 SW Dosch Park Ln* 142 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 4825 SW Dosch Park Ln* H 73-120, S 64-100, C 12-12.4 143 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 4825 SW Dosch Park Ln* 157 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) SW Patton Rd, Portland Heights Park H 87, S 94, C 17 171 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) SW Macadam & Nevada, Willamette Park H 102, S 72, C 17 179 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) SW Corbett & Lane, Corbett Oak Park H 73, S 73, C 13.3 198 Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) 199 200 7654 N. -

Acorn Planting

Oak Harbor Garry Oak (Quercus garryana) Acorn Planting 10/09/14 by Brad Gluth Acorn Acquisition 1) Garry oak acorns have to be collected and planted in the Autumn that they are shed from the trees unless stored in refrigeration. 2) Gather acorns from beneath local trees only. Oaks hybridize easily and we are trying to preserve the genetics of the local trees. Acorn Selection 3) Float test the acorns. Place the acorns in a container of water. Remove and discard those that float. This is a density test and the floating acorns have been compromised through pests or other causes. Select the largest acorns from those that sank for planting. The larger acorns have more vigorous seedling growth. 4) Do not allow the acorns to dry out. It is best to not store them indoors. Planting Containers 5) Pots should be a minimum of 10” deep with drain holes. (Garry oaks quickly develop a deep tap root of up to 10” in the first season.) Soil Mix 6) The soil mix should be a well-draining mix. Sand mixed with potting soil works well. Planting 7) Soak acorns in water for 5 to 10 minutes prior to planting. 8) Plant 2-3 of the largest acorns on their side in each pot. Cover each acorn with about 1/4” of soil. (If more than one acorn germinates, the seedlings can be thinned, or separated from the pots for replanting.) 9) After planting, 1” of mulch should be placed on top of the soil. If available, oak leaf mulch is recommended. -

Quercus Garryana Pacific University Oregon White Oak Rehabilitation Case Study Jared Kawatani, ‘17 Center for a Sustainable Society, Pacific University

Quercus garryana Pacific University Oregon White Oak Rehabilitation Case Study Jared Kawatani, ‘17 Center for a Sustainable Society, Pacific University Introduction Quercus garryana can be found in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. Some of its common names are: Gary Oak, Oregon White Oak, and Oregon Oak. They are large slow growing hardwood trees that grow in woodlands, savannahs, and prairies. They are very versatile trees as they can grown in cool climates, humid coastal climates to hot, dry inland environments. But they prefer moist, fertile sites over the very dry conditions that they can grow in as well. Unfortunately, there are multiple problems that Oregon white oaks face over all as a species on the west coast. One of those issues is that they are threatened by the encroachment of other trees because they are sun loving and have a low tolerance for shade and thus get outcompeted. Historical records show this encroachment originally started to occur due to a loss of forest fire management done by the Native Americans in the area. These fires played a part in preventing the woodlands, savannahs, and prairies from being encroached on by the surrounding forests, and prevent bugs from eating the acorns that the Native Americans preferring to eat. The oaks have adapted to the environment that the Native Americans had created. Not only are they being out competed by the Douglas firs, their habitats are being lost to development. Oregon white oaks are also threatened by sudden oak death by the plant pathogen Phytophthora ramorum that was found in the south range of the trees (California and southern Oregon). -

Vegetation Classification for San Juan Island National Historical Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science San Juan Island National Historical Park Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR—2012/603 ON THE COVER Red fescue (Festuca rubra) grassland association at American Camp, San Juan Island National Historical Park. Photograph by: Joe Rocchio San Juan Island National Historical Park Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR—2012/603 F. Joseph Rocchio and Rex C. Crawford Natural Heritage Program Washington Department of Natural Resources 1111 Washington Street SE Olympia, Washington 98504-7014 Catharine Copass National Park Service North Coast and Cascades Network Olympic National Park 600 E. Park Ave. Port Angeles, Washington 98362 . December 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization. -

Stand Structures of Oregon White Oak Woodlands, Regeneration, and Their Relationships to the Environment in Southwestern Oregon

Laurie A. Gilligan1 and Patricia S. Muir, Oregon State University, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 2082 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Stand Structures of Oregon White Oak Woodlands, Regeneration, and Their Relationships to the Environment in Southwestern Oregon Abstract Although Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) woodlands are a characteristic landscape component in southwestern Or- egon, little is known about their current or historical stand structures. Meanwhile, fuel reduction thinning treatments that change stand structures in non-coniferous communities are ongoing and widespread on public lands in this region; some of these treatments also have restoration objectives. Managers need baseline information on which to base prescriptions that have a restoration focus. We inventoried 40 Oregon white oak dominated woodlands across two study areas in southwestern Oregon, and describe here their stand characteristics and age structures. We assessed whether these varied systematically with site conditions or recorded fire history. Stands included various proportions of single- and multiple-stemmed trees and a range of tree densities and diameter- and age-class distributions. Variables that may indicate site moisture status were weakly associated with multivariate gradients in stand structure. Peak establishment of living Oregon white oaks generally occurred during 1850-1890, sometimes occurred in the early 1900s, and recruitment rates were low post-fire suppression (~1956). Recruitment of sapling-sized oak trees (<10 cm diameter at breast height, q 1.3 m tall) was generally low and their ages ranged from 5 to 164 yr; they were not necessarily recent recruits. The observed wide range of variability in stand characteristics likely reflects the diversity of mechanisms that has shaped them, and suggests that a uniform thinning approach is unlikely to foster this natural range of variability. -

Dendrochronology Across Borders: Developing a Network of Quercus Garryana Tree-Ring Chronologies for the Pacific Northwest

DENDROCHRONOLOGY ACROSS BORDERS: DEVELOPING A NETWORK OF QUERCUS GARRYANA TREE-RING CHRONOLOGIES FOR THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST David A. Jordan1, Gabriel I. Yospin2, Bart R. Johnson3, and Doug McCutchen4 1 Department of Geography and Environment, Trinity Western University, Langley, BC 2 InsUtute on Ecosystems, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 3 Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 4 San Juan County Land Bank, Friday Harbour, WA Cascadia Prairie Oak Partnership 2015 Conference, October 26-29, 2015, Tacoma, Washington CONSERVATION WITHOUT BORDERS: Working Across Boundaries to Restore Prairie and Oak CommuniMes Acknowledgements Co-authors: Dr. Bart Johnson, University of Oregon, Dr. Gabe Yospin, University of Oregon/ Montana State Univ Co-author: Doug McCutchen, Ruthie Dougherty, Steve Ulvi Jane KerMs, U.S. Forest Service, Staff at Finley Nature Refuge City of Victoria Parks staff: Thomas Munson, Dan MarZoco and Craig Pelton Research funding provided by Naonal Science Foundaon Outline 1. Background • The problem, why does it maer, goals and objecves 2. Methods • Dendrochronology (Tree-ring science) • Field and Laboratory • Study Areas 3. Results and Discussion 4. Summary Background:The fate of oak habitat? 44% Agriculture 30% Forest 14% Other natural vegetaUon 8% Built features 4% Unknown 2-10% remains, 90-95% on private land Hulse, Gregory and Baker. 2002. Willame[e River Basin planning atlas Background: Why does it maYer? Willame[e Valley oak savanna & woodland: • >95 nave vertebrate species associated w/ Willame[e Valley grasslands (Veseley and Rosenberg 2010) • >714 nave plant species of which more than 391 are found principally or exclusively in grassland habitats (Ed Alverson, TNC, unpublished data). -

Quercus Garryana) in Central Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1981 The biogeography of Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) in central Oregon Robert Allen Voeks Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Spatial Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Voeks, Robert Allen, "The biogeography of Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) in central Oregon" (1981). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3545. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5429 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Robert Allen Voeks for the Master of Science in Geography presented April, 1981. Title: The Biogeography of Oregon White Oak (Quercus garryana) in Central Oregon. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Larry Price, C~,9':i.rman Clarke Brooke Robert Tinnin 2 ABSTRACT Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) is distributed along a north-south swath from British Columbia to central California, bounded on the west by the Coast Range and on the east by the Sierra/Cascade cordillera. It departs from this li~ear path near latitude 46°N, where it passes east through the Columbia River Gorge into central Oregon and Washington. Here it occupies a distinct eastern Cascade foothill zone between Douglas fir/ponder osa pine associations and juniper/sagebrush/grassland habitats. This thesis examines g_. -

Western Gray Squirrel Recovery Plan

STATE OF WASHINGTON November 2007 Western Gray Squirrel Recovery Plan by Mary J. Linders and Derek W. Stinson by Mary J. Linders and Derek W. Stinson Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE Wildlife Program In 1990, the Washington Wildlife Commission adopted procedures for listing and de-listing species as en- dangered, threatened, or sensitive and for writing recovery and management plans for listed species (WAC 232-12-297, Appendix E). The procedures, developed by a group of citizens, interest groups, and state and federal agencies, require preparation of recovery plans for species listed as threatened or endangered. Recovery, as defined by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is the process by which the decline of an en- dangered or threatened species is arrested or reversed, and threats to its survival are neutralized, so that its long-term survival in nature can be ensured. This is the final Washington State Recovery Plan for the Western Gray Squirrel. It summarizes the historic and current distribution and abundance of western gray squirrels in Washington and describes factors af- fecting the population and its habitat. It prescribes strategies to recover the species, such as protecting the population and existing habitat, evaluating and restoring habitat, potential reintroduction of western gray squirrels into vacant habitat, and initiating research and cooperative programs. Interim target population objectives and other criteria for reclassification are identified. The draft state recovery plan for the western gray squirrel was reviewed by researchers and representatives from state, county, local, tribal, and federal agencies, and regional experts. This review was followed by a 90-day public comment period. -

Distribution. Th

QUGA4 6 OREGON WHITE OAK/HEDGEHOG DOGTAIL Quercus garryana/Cynosurus echinatus QUGA4/CYEC (N=43; BLM=39, FS=4) Distribution. This Association occurs on the North Umpqua and Tiller Ranger Districts, Umpqua National Forest, the Grants Pass, Ashland, and Butte Falls Resource Areas, Medford District, and the Swiftwater Resource Area, Roseburg District, Bureau of Land Management. It may also occur on the Galice and Illinois Valley Ranger Districts, Siskiyou National Forest, and all Districts of the Rogue River National Forest. Distinguishing Characteristics. Douglas-fir is generally absent. This Association supports high grass species richness (approximately 18 species). Herb/grass cover is high. The average annual temperature is 50 degrees F and the average annual precipitation is 33 inches, drier than the Oregon White Oak-Douglas-fir/Poison Oak Association. Soils. Parent material is variable, consisting of meta-volcanics, serpentine, basalt, QUGA4 7 tuffs, sandstone, mixed-sediments, welded tuffs, and andesite. Surface gravel, rock, and bedrock covers are low, averaging less than 6 percent for each component. Based on four plots sampled, soils are shallow to moderately deep and well drained. The surface texture is silt loam or loam, with 0 to 22 percent gravel, 5 to 25 percent cobbles, and 21 to 25 percent clay. Subsurface textures are silty clay loams or clay loams, with 0 to 10 percent gravel, 0 to 25 percent cobbles, and 35 percent clay. The soil moisture regime is probably xeric and the soil temperature regime is probably mesic. Soils classify to the following subgroups: Typic Haploxeroll, Lithic Haploxeroll, and Lithic Argixeroll. Environment. Elevation averages 2130 feet.