Inequality: the Facts and the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

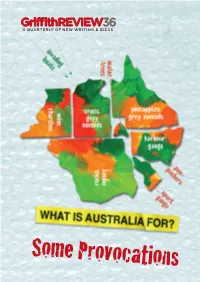

Griffith REVIEW Editon 36: What Is Australia For?

36 A QUARTERLY OF NEW WRITING & IDEAS ESSAYS & MEMOIR, FICTION & REPORTAGE Frank Moorhouse, Kim Mahood, Jim Davidson, Robyn Archer Dennis Altman, Michael Wesley, Nick Bryant, Leah Kaminsky, Romy Ash, David Astle, Some Provocations Peter Mares, Cameron Muir, Bruce Pascoe GriffithREVIEW36 SOME PROVOCATIONS eISBN 978-0-9873135-0-8 Publisher Marilyn McMeniman AM Editor Julianne Schultz AM Deputy Editor Nicholas Bray Production Manager Paul Thwaites Proofreader Alan Vaarwerk Editorial Interns Alecia Wood, Michelle Chitts, Coco McGrath Administration Andrea Huynh GRIFFITH REVIEW South Bank Campus, Griffith University PO Box 3370, South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Ph +617 3735 3071 Fax +617 3735 3272 [email protected] www.griffithreview.com TEXT PUBLISHING Swann House, 22 William St, Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia Ph +613 8610 4500 Fax +613 9629 8621 [email protected] www.textpublishing.com.au SUBSCRIPTIONS Within Australia: 1 year (4 editions) $111.80 RRP, inc. P&H and GST Outside Australia: 1 year (4 editions) A$161.80 RRP, inc. P&H Institutional and bulk rates available on application. COPYRIGHT The copyright of all material published in Griffith REVIEW and on its website remains the property of the author, artist or photographer, and is subject to copyright laws. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. ||| Opinions published in Griffith REVIEW are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, Griffith University or Text Publishing. FEEDBACK AND COMMENT www.griffithreview.com ADVERTISING Each issue of Griffith REVIEW has a circulation of at least 4,000 copies. Full-page adverts are available to selected advertisers. -

Political Finance in Australia

Political finance in Australia: A skewed and secret system Prepared by Sally Young and Joo-Cheong Tham for the Democratic Audit of Australia School of Social Sciences The Australian National University Report No.7 Table of contents An immigrant society PAGE ii The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be The Democratic Audit of Australia vii PAGE iii taken to represent the views of either the Democratic Audit of Australia or The Tables iv Australian National University Figures v Abbreviations v © The Australian National University 2006 Executive Summary ix National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data 1 Money, politics and the law: Young, Sally. Questions for Australian democracy Political Joo-Cheong Tham 1 Bibliography 2 Private funding of political parties Political finance in Australia: a skewed and secret system. Joo-Cheong Tham 8 ISBN 0 9775571 0 3 (pbk). 3 Public funding of political parties Sally Young 36 ISBN 0 9775571 1 1 (online). 4 Government and the advantages of office 1. Campaign funds - Australia. I. Tham, Joo-Cheong. II. Sally Young 61 Australian National University. Democratic Audit of 5 Party expenditure Australia. III. Title. (Series: Democratic Audit of Sally Young 90 Australia focussed audit; 7). 6 Questions for reform Joo-Cheong Tham and Sally Young 112 324.780994 7 Conclusion: A skewed and secret system 140 An online version of this paper can be found by going to the Democratic Audit of Australia website at: http://democratic.audit.anu.edu.au References and further -

Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia's

PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment This research paper is a project of the Chifley Research Centre, the official think tank of the Australian Labor Party. This paper has been prepared in conjunction with the Labor Environment Action Network (LEAN). The report is not a policy document of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party. Publication details: Wade, Felicity. Gale, Brett. “Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment” Chifley Research Centre, November 2018. PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment FOREWORD Australians are immensely proud of our natural environment. From our golden beaches to our verdant rainforests, Australia seems to be a nation blessed with an abundance of nature’s riches. Our natural environment has played a starring role in Australian movies and books and it is one of our key selling points in attracting tourists down under. We pride ourselves on our clean, green country and its contrast to many other places around the world. Why is it then that in recent decades pride in our The mission of the Chifley Research Centre (CRC) is to natural environment has very rarely translated into champion a Labor culture of ideas. The CRC’s policy action to protect it? work aims to set the groundwork for a fairer and more progressive Australia. Establishing a long-term agenda We have one of the highest rates of fauna extinctions for solving societal problems for progressive ends in the world, globally significant rates of deforestation, is a key aspect of the work undertaken by the CRC. plastics clogging our waterways, and in many regions, The research undertaken by the CRC is designed to diminishing air, water and soil quality threaten human stimulate public policy debate on issues outside of day wellbeing and productivity. -

PUBLISHED VERSION Carol Johnson "Incorporating Gender Equality : Tensions and Synergies in the Relationship Between Feminism and Australian Social Democracy"

PUBLISHED VERSION Carol Johnson "Incorporating gender equality : tensions and synergies in the relationship between feminism and Australian social democracy" Copyright the Author PERMISSIONS Copyright the Author 23 September, 2016 http://hdl.handle.net/2440/101240 “Incorporating gender equality: Tensions and synergies in the relationship between feminism and Australian social democracy.” Carol Johnson Politics and International Studies Department, University of Adelaide “Incorporating gender equality: Tensions and synergies in the relationship between feminism 36 and Australian social democracy.” This essay focuses on exploring the tensions and synergies in the relationship between feminism and social democracy via an analysis of Australian Labor governments. The Australian Labor Party (ALP) is Australia’s longstanding social democratic party and one of the first in the world to achieve government.1 Yet, it is important to recognise that without the influence of feminism, social democracy in Australia (as elsewhere) would have been a much diminished movement that risked representing only half of the population, not only in terms of policy but also in terms of gender representation. As late as 1973, Gough Whitlam (1973: 1152) acknowledged that the ALP was “a male dominated Party, in a male dominated Parliament in a male dominated society”. Indeed, there were no female Labor members of parliament at that time (Whitlam 1973: 1152).2 Twenty years later, there were still only nine female Labor members of the House of Representatives and four -

A Passion for Policy

A Passion for Policy Essays in Public Sector Reform A Passion for Policy Essays in Public Sector Reform Edited by John Wanna Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/policy_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Wanna, John. A passion for policy : ANZOG lecture series 2005-2006. ISBN 9781921313349 (pbk.). ISBN 9781921313356 (web). 1. Policy sciences. 2. Political planning - Australia. I. Australia and New Zealand School of Government. II. Title. (Series : ANSOG monographs). 320.60994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2007 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). He is also a joint appointment with the Department of Politics and Public Policy at Griffith University and a principal researcher with two research centres: the Governance and Public Policy Research Centre and the nationally-funded Key Centre in Ethics, Law, Justice and Governance at Griffith University. -

Make Australia Fair Again: the Case for Employee Representation on Company Boards

Make Australia Fair Again: the Case for Employee Representation on Company Boards The Australian way of life is premised on a basic set of assumptions: decent pay, working conditions and job security, a fair say for working women and men in our workplaces and parliaments, and a fair say in the nation’s civic life. In 2017, the Australian way is fraying. Globalisation and technological disruption, declining manufacturing and the collapse of mass unionism paired with decentralised wage determination, have combined to challenge its core ethos. Full-time jobs are declining in favour of part-time, casualised and precarious contract work. Wage theft and workplace exploitation is rife. Company profits grow apace yet annual wages growth is at record low rates, underpinning levels of inequality not seen since the 1940s. There is abundant evidence that the fruits of 26 years of continuous, record national economic growth have not been shared equally. The erosion of the Australian way is not just bad for working people but bad for the national economy and bad for our democracy, and at odds with the national interest. To address the big challenges facing our country we need to fashion a new politics of the common good. In this second John Curtin Research Centre policy essay Nick Dyrenfurth makes the case for employee representation on company boards. This vital reform to our corporate governance, he argues, is necessary to rebuild a pro-worker, pro-business economy: fostering workplace cooperation, boosting productivity, and tackling rising inequality and stagnating real wages. No less than the future of the Australian way is at stake. -

Accepted Version

ACCEPTED VERSION Carol Johnson The Australian Right in the “Asian Century”: Inequality and the Implications for Social Democracy Journal of Contemporary Asia, 2018; 48(4):1-27 © 2018 Journal of Contemporary Asia This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Journal of Contemporary Asia 06 Mar 2018 available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1441894 PERMISSIONS http://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/sharing-your-work/ Accepted Manuscript (AM) As a Taylor & Francis author, you can post your Accepted Manuscript (AM) on your personal website at any point after publication of your article (this includes posting to Facebook, Google groups, and LinkedIn, and linking from Twitter). To encourage citation of your work we recommend that you insert a link from your posted AM to the published article on Taylor & Francis Online with the following text: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in [JOURNAL TITLE] on [date of publication], available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/[Article DOI].” For example: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Africa Review on 17/04/2014, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/12345678.1234.123456. N.B. Using a real DOI will form a link to the Version of Record on Taylor & Francis Online. The AM is defined by the National Information Standards Organization as: “The version of a journal article that has been accepted for publication in a journal.” This means the version that has been through peer review and been accepted by a journal editor. -

Reclaiming Progressive Australia Demographic Change and Progressive Political Strategy in Australia

Reclaiming Progressive Australia Demographic Change and Progressive Political Strategy in Australia The Chifley Research Centre April 2011 The “Demographic Change and Progressive Political Strategy” series of papers is a joint project organized under the auspices of the Global Progress and Progressive Studies programs and the Center for American Progress. The research project was launched following the inaugural Global Progress conference held in October 2009 in Madrid, Spain. The preparatory paper for that conference, “The European Paradox,” sought to analyze why the fortunes of European progressive parties had declined following the previous autumn’s sudden financial collapse and the global economic recession that ensued. The starting premise was that progressives should, in principle, have had two strengths going for them: • Modernizing trends were shifting the demographic terrain in their political favor. • The intellectual and policy bankruptcy of conservatism, which had now proven itself devoid of creative ideas of how to shape the global economic system for the common good. Despite these latent advantages, we surmised that progressives in Europe were struggling for three pri- mary reasons. First, it was increasingly hard to differentiate themselves from conservative opponents who seemed to be wholeheartedly adopting social democratic policies and language in response to the eco- nomic crisis. Second, the nominally progressive majority within their electorate was being split between competing progressive movements. Third, their traditional working-class base was increasingly being seduced by a politics of identity rather than economic arguments. In response, we argued that if progressives could define their long-term economic agenda more clearly— and thus differentiate themselves from conservatives—as well as establish broader and more inclusive electoral coalitions, and organize more effectively among their core constituencies to convey their mes- sage, then they should be able to resolve this paradox. -

Dissenting Report

Annexure A BOO Kendall Schedule A (Pages 9-10/26 of the BOO Kendall Report.) ATM Cash Withdrawal Transactions Commonwealth Bank Mastercard- Mr Craig Thomson Schedule A covering the period 13th April 2007 24th November 2007. 1.50 500.00 1.50 300.00 1.50 500.00 1.50 300.00 1.25 500.00 1.25 500.00 1.50 500.00 1.50 500.00 it 1.50 500.00 1.25 400.00 1.50 500.00 1;50' 500.00 1.50 g~ 500.00 1.25 500.00 ?.~ 1.50 500.00 ..... ·. 1 ..50 500,00' 1.50 500.00 1:5.0 500.00 1'.25 500.00 1.50 50000 1.50 500.00 1.$0 500.00 1.25 500.00 1.50 500.00 1.50 500.00 1.50 300.00 1.50 500.00 1:25 500.00 1.25 Page 9 of26 · - -~ :cl ~ ocu!G of ATM Cash Withdrawal Transactions ;ommonwealth B ank Mastercard - r•!ir. Craig Thc:m;on Scheduie A :ard No.: 5587 0131 6388 0019 >ate ATM Amount )8/10//.007 CBA ATM TERRIGAL. NSW 500.00 )8/10/2007 CBA CASH ADV CHRG 1.25 )9/10/2007 CBA AT tVI EASTERN BCH C 500.00 J9i1 0/2007 CBA CASH ADV CHRG 1.25 16/10/2007 CBA ATM BAY VILLAGE NSW 500.00 16'10/2007 CBA CASH ADV CHRG 1.25 22110/2007 CBA BATEAU BAY NSW 500.00 22/10/2007 CBA CASH ADV CHRG 1.25 30/10/2007 CBA BATEAU BAY NSW 500.00 30/10/2007 CBA CASH ADV CHRG 1.25 01/11/2007 AAMI GOSFORD 500.00 ; 01/11/2007 NON CBA ATM CASH ADV CHARGE 1.50 05/11/2007 CBA BATEAU BAY NSW 500.00 05/11/2007 CBA CASH AOV CHRG 1.25 12/11/2007 CBA BATEAU BAY NSW 500.00 12/11/2007 CBA CASH AOV CHRG 1.25 ~ ~-/11/2007 NAB KILLARNEY VALE 500.00 .i11/2007 CBA CASH AOV CHRG 1.25 102,034.45 Page 10 of26 Annexure B list of Reviews completed since 2007 list of Reviews completed since 2007 Year Party/Entity 2007 -

The Tocsin | Issue 4, 2018

Contents The Tocsin | Issue 4, 2018. Editorial | 4 Launch of JCRC|Vision Super Richard Marles delivers the policy report | Page 11 2018 John Curtin Lecture | 5 Jim Chalmers launches Super Ideas report | 11 Nick Dyrenfurth – Super Ideas |14 On the road: JCRC events in images| 16 Adam Slonim – Foreign Choices | 18 Mike Kelly – Labor and National Security | 21 Michael Easson pays his respects to two labour movement icons | 27 Getting to know … JCRC Deputy Chair Adam Slonim responds to the 2017 Andrew Porter | 32 Foreign Policy White Paper | Page 18 JCRC in the news | 34 Mike Kelly outlines Labor’s national security agenda | Page 21 The Tocsin, Flagship Publication of the John Curtin Research Centre. Issue 4, 2018. Copyright © 2018 All rights reserved. Editor: Nick Dyrenfurth | [email protected] www.curtinrc.org www.facebook.com/curtinrc/ twitter.com/curtin_rc 3 Editorial Executive Director, Dr Nick Dyrenfurth ‘There has never been a more exciting time to be an Andrew’s memory be a blessing; I wish his family a Australian’. It was a laughable statement when Liberal long life. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull assumed the nation’s top job in September 2015. But for working Published in tandem with this edition the John Australians in 2018 it is nothing short of a sick joke. Curtin Research is delighted to release a special According to a recent Australian Council of Trade discussion paper on Trumpism and the lessons for Unions survey, more than 70 per cent of workers social democrats in the United States, with much say they are working harder for less, are expected to food for thought for those of us down under. -

LETTER from CANBERRA Saving You Time

LETTER FROM CANBERRA Saving you time. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. 19 MAY TO 17 JUNE 2010 Issue No. 25: Winter Edition (in much of Australia) Letter From Canberra, established 2008, is a sister publication of Letter From Melbourne, established 1994 INSIDE Minerals PM’s Malcolm Obama’s visit Israel’s diplomat Australia’s Unlimited Minimum wage tax debate popularity Turnbull’s back on hold again told to take new advertising up. More union lengthens slips more with his ETS plan passport and go campaign demands on way What Australians in each State believe are the ‘Most important problems facing Australia.’ - Pages 11-13 19 MAY TO 17 JUNE 2010 14 Collins Street Melbourne, 3000 EDITORIAL: SURPRISES ALL ROUND Victoria, Australia Some things come seemingly out of nowhere. Tony Abbott’s discussion on what is the truth! Queensland P 03 9654 1300 F 03 9654 1165 MP Michael Johnson’s issues with coal commissions! Turnbull (quietly) applying pressure to the Government on the ETS! The on-going resources tax issue, including the advertisements that are coming [email protected] www.letterfromcanberra.com.au out from both/various sides to this particular debate! And now the government advertisements on health and the national broadband network, spelling out all of the facts! The media is having a field day. And will also earn some serious criticism. The media wants respect, or some of them do. They need respect from politicians! None of this ‘pass the parcel’ stuff.. It will be a very weird and nasty election. -

Letters Chronicle Politics

June2013 No.497 VolumeLVII,Number6 , Frank Pulsford, Jan Cooper, Damien Cremean, Sam Bateman Letters 2 Harvey Broadbent, John Williams Keith Windschuttle chronicle 5 Daryl McCann Legacy Rudd–Gillard the of Ruins the Raking politics 7 Michael O’Connor Issue Election an Be Not Will Defence Why 12 Ron Wilson Monash to Came Thatcher Margaret When 16 Robert Conquest James Clive of Verse Extraordinary The poetry 18 Gregory Haines Trailblazer a as Career Kramer’s Leonie biography 22 Peter Coleman (I) Arts Liberal the of Cultivation The universities 26 Keith Windschuttle (II) Arts Liberal the of Cultivation The 28 Julia Patrick Philosophy Sixties of Ravages Social The society 30 Christopher Akehurst Marriage of Faces Two The 34 Zachary Gorman Party Liberal the of Father Founding Forgotten The history 36 Exchange and Barter Truck, to Propensity the and Smith Adam economics 40 Ray Evans 44 Keynes as Social Philosopher Geoffrey Luck Wolfgang Kasper Alps the in Prosperity of Pocket A europe 50 Modernists Christopher Heathcote the of Exodus the and Clark Kenneth art 58 Stephen Buckle Theory Political Feminist in Spot Blind The philosophy&ideas 68 Michael Connor Affairs Family theatre 72 J.B. Paul Judiciary the and Powers Reserve The law 76 Michael Giffin Reason of Limitation The religion 79 Iain Bamforth Tree Upas The science 82 Maurice Nestor Shapes Storm Sounds, Storm firstperson 88 Best Overend 1937 Force, Police Volunteer Shanghai the with Duty On 92 Alan Gould Collected Neglected the and Anthology Ubiquitous The poetry 98 Neil McDonald Achievement Ealing The film 100 Morris Lurie Pain Show to Ways Many Are There story 105 Patrick Morgan Windle Kevin by Undesirable books 108 Tanveer Ahmed Kahn P.