Political Finance in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Misconduct: the Case for a Federal Icac

MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS A HISTORY OF MISCONDUCT: THE CASE FOR A FEDERAL ICAC INDEPENDENT JO URNALISTS MICH AEL WES T A ND CALLUM F OOTE, COMMISSIONED B Y G ETUP 1 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS MISCONDUCT IN RESOURCES, WATER AND LAND MANAGEMENT Page 5 MISCONDUCT RELATED TO UNDISCLOSED CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Page 8 POTENTIAL MISCONDUCT IN LOBBYING MISCONDUCT ACTIVITIES RELATED TO Page 11 INAPPROPRIATE USE OF TRANSPORT Page 13 POLITICAL DONATION SCANDALS Page 14 FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON THE POLITICAL PROCESS Page 16 ALLEGEDLY FRAUDULENT PRACTICES Page 17 CURRENT CORRUPTION WATCHDOG PROPOSALS Page 20 2 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS FOREWORD: Trust in government has never been so low. This crisis in public confidence is driven by the widespread perception that politics is corrupt and politicians and public servants have failed to be held accountable. This report identifies the political scandals of the and other misuse of public money involving last six years and the failure of our elected leaders government grants. At the direction of a minister, to properly investigate this misconduct. public money was targeted at voters in marginal electorates just before a Federal Election, In 1984, customs officers discovered a teddy bear potentially affecting the course of government in in the luggage of Federal Government minister Australia. Mick Young and his wife. It had not been declared on the Minister’s customs declaration. Young This cheating on an industrial scale reflects a stepped aside as a minister while an investigation political culture which is evolving dangerously. into the “Paddington Bear Affair” took place. The weapons of the state are deployed against journalists reporting on politics, and whistleblowers That was during the prime ministership of Bob in the public service - while at the same time we Hawke. -

1 Hyperlinks and Networked Communication: a Comparative

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The Australian National University 1 Hyperlinks and Networked Communication: A Comparative Study of Political Parties Online This is a pre-print for: R. Ackland and R. Gibson (2013), “Hyperlinks and Networked Communication: A Comparative Study of Political Parties Online,” International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(3), special issue on Computational Social Science: Research Strategies, Design & Methods, 231-244. Dr. Robert Ackland, Research Fellow at the Australian Demographic and Social Research Institute, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia *Professor Rachel Gibson, Professor of Politics, Institute for Social Change, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. *Corresponding author: Professor Rachel Gibson Institute for Social Change University of Manchester, Oxford Road Manchester M13 9PL UK Ph: + 44 (0)161 306 6933 Fax: +44 (0) 161 275 0793 [email protected] Word count: 6,062(excl title page and key words) 2 Abstract This paper analyses hyperlink data from over 100 political parties in six countries to show how political actors are using links to engage in a new form of ‘networked communication’ to promote themselves to an online audience. We specify three types of networked communication - identity reinforcement, force multiplication and opponent dismissal - and hypothesise variance in their performance based on key party variables of size and ideological outlook. We test our hypotheses using an original comparative hyperlink dataset. The findings support expectations that hyperlinks are being used for networked communication by parties, with identity reinforcement and force multiplication being more common than opponent dismissal. The results are important in demonstrating the wider communicative significance of hyperlinks, in addition to their structural properties as linkage devices for websites. -

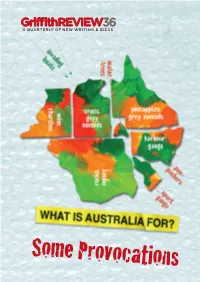

Griffith REVIEW Editon 36: What Is Australia For?

36 A QUARTERLY OF NEW WRITING & IDEAS ESSAYS & MEMOIR, FICTION & REPORTAGE Frank Moorhouse, Kim Mahood, Jim Davidson, Robyn Archer Dennis Altman, Michael Wesley, Nick Bryant, Leah Kaminsky, Romy Ash, David Astle, Some Provocations Peter Mares, Cameron Muir, Bruce Pascoe GriffithREVIEW36 SOME PROVOCATIONS eISBN 978-0-9873135-0-8 Publisher Marilyn McMeniman AM Editor Julianne Schultz AM Deputy Editor Nicholas Bray Production Manager Paul Thwaites Proofreader Alan Vaarwerk Editorial Interns Alecia Wood, Michelle Chitts, Coco McGrath Administration Andrea Huynh GRIFFITH REVIEW South Bank Campus, Griffith University PO Box 3370, South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Ph +617 3735 3071 Fax +617 3735 3272 [email protected] www.griffithreview.com TEXT PUBLISHING Swann House, 22 William St, Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia Ph +613 8610 4500 Fax +613 9629 8621 [email protected] www.textpublishing.com.au SUBSCRIPTIONS Within Australia: 1 year (4 editions) $111.80 RRP, inc. P&H and GST Outside Australia: 1 year (4 editions) A$161.80 RRP, inc. P&H Institutional and bulk rates available on application. COPYRIGHT The copyright of all material published in Griffith REVIEW and on its website remains the property of the author, artist or photographer, and is subject to copyright laws. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. ||| Opinions published in Griffith REVIEW are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, Griffith University or Text Publishing. FEEDBACK AND COMMENT www.griffithreview.com ADVERTISING Each issue of Griffith REVIEW has a circulation of at least 4,000 copies. Full-page adverts are available to selected advertisers. -

Short Report

AUSTRALIAN EPHEMERA COLLECTION FINDING AID FORMED COLLECTION FEDERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGNS, 1901-2014 PRINTED AUSTRALIANA AUGUST 2017 The Library has been actively collecting Federal election campaign ephemera for many years. ACCESS The Australian Federal Elections ephemera may requested by eCall-slip and used through the Library’s Special Collections Reading Room. Readers are able to request files relating to a specific election year. Please note: . 1901-1913 election material all in one box . 1914-1917 election material all in one box OTHER COLLECTIONS See also the collection of related broadsides and posters, and within the PANDORA archive. See also ‘Referenda’ in the general ephemera run. CONTENT AND ARRANGEMENT OF THE COLLECTION 1901 29-30 March see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period 1903 16 December see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period 1906 12 December see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period 1910 13 April see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. Australian Labour Party Folder 2. Liberal Party 1913 31 May see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. Australian Labor Party Folder 2. Liberal Party Folder 3. Other candidates 1914 ― 5 September (double dissolution) see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. Australian Labor Party Folder 2. Liberal Party 1917 5 May see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. Australian Labor Party Folder 2. National Party Folder 3. Other candidates 1919 13 December see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

1 Heat Treatment This Is a List of Greenhouse Gas Emitting

Heat treatment This is a list of greenhouse gas emitting companies and peak industry bodies and the firms they employ to lobby government. It is based on data from the federal and state lobbying registers.* Client Industry Lobby Company AGL Energy Oil and Gas Enhance Corporate Lobbyists registered with Enhance Lobbyist Background Limited Pty Ltd Corporate Pty Ltd* James (Jim) Peter Elder Former Labor Deputy Premier and Minister for State Development and Trade (Queensland) Kirsten Wishart - Michael Todd Former adviser to Queensland Premier Peter Beattie Mike Smith Policy adviser to the Queensland Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, LHMU industrial officer, state secretary to the NT Labor party. Nicholas James Park Former staffer to Federal Coalition MPs and Senators in the portfolios of: Energy and Resources, Land and Property Development, IT and Telecommunications, Gaming and Tourism. Samuel Sydney Doumany Former Queensland Liberal Attorney General and Minister for Justice Terence John Kempnich Former political adviser in the Queensland Labor and ACT Governments AGL Energy Oil and Gas Government Relations Lobbyists registered with Government Lobbyist Background Limited Australia advisory Pty Relations Australia advisory Pty Ltd* Ltd Damian Francis O’Connor Former assistant General Secretary within the NSW Australian Labor Party Elizabeth Waterland Ian Armstrong - Jacqueline Pace - * All lobbyists registered with individual firms do not necessarily work for all of that firm’s clients. Lobby lists are updated regularly. This -

JSCEM Submission K Bonham

Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters: Inquiry into and report on all aspects of the conduct of the 2013 Federal Election and matters related thereto. by Dr Kevin Bonham, submitted 10 April 2014 Summary This submission concerns the system for voting in Senate elections. Following the 2013 Australian federal elections, the existing Senate system of group ticket voting is argued to be broken on account of the following problems: * Candidates being elected through methods other than genuine voter intention from very low primary votes. * Election outcomes depending on irrelevant events involving uncompetitive parties early in preference distributions. * The frequent appearance of perverse outcomes in which a party would have been more successful had it at some stage had fewer votes. * Oversized ballot papers, contributing to confusion between similarly-named parties. * Absurd preference deals and strategies, resulting in parties assigning their preferences to parties their supporters would be expected to oppose. * The greatly increased risk of close results that are then more prone to being voided as a result of mistakes by electoral authorities. This submission recommends reform of the Senate system. The main proposed reform recommended is the replacement of Group Ticket Voting with a system in which a voter can choose to: * vote above the line for one or more parties, with preferences distributed to those parties and no other; or * vote below the line with preferences to at least a prescribed minimum number of candidates -

Copyright by Gregory Scott Brown 2004 the Dissertation Committee for Gregory Scott Brown Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Gregory Scott Brown 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Gregory Scott Brown Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Coping with Long-distance Nationalism: Inter-ethnic Conflict in a Diaspora Context Committee: Gary P. Freeman, Supervisor John Higley Zoltan Barany Alan Kessler Ross Terrill Coping with Long-distance Nationalism: Inter-ethnic Conflict in a Diaspora Context by Gregory Scott Brown, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2004 Dedication To Dale Acknowledgements Many people helped me finish this dissertation and deserve thanks. My advisor, Gary Freeman, provided guidance, encouragement, and a helpful prod now and again. I owe him a special debt for his generous support and patience. Special thanks are also due John Higley who provided personal and institutional support throughout the process—even when he had neither the time nor obligation to do so. I also thank the other members of my dissertation committee, Ross Terrill, Alan Kessler, and Zoltan Barany. Each of them offered sound advice and counsel during my fieldwork and the writing phase of this project. I also benefited greatly from numerous funding programs; including, the Edward A. Clark Center for Australian and New Zealand Studies, the Australian and New Zealand Studies Association of North America, and various funding sources in the Department of Government, UT-Austin. My fieldwork was also facilitated by generous support from the Australian Centre at Melbourne University and the Parliamentary Internship/Public Policy program at the Australian National University. -

Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia's

PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment This research paper is a project of the Chifley Research Centre, the official think tank of the Australian Labor Party. This paper has been prepared in conjunction with the Labor Environment Action Network (LEAN). The report is not a policy document of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party. Publication details: Wade, Felicity. Gale, Brett. “Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment” Chifley Research Centre, November 2018. PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment FOREWORD Australians are immensely proud of our natural environment. From our golden beaches to our verdant rainforests, Australia seems to be a nation blessed with an abundance of nature’s riches. Our natural environment has played a starring role in Australian movies and books and it is one of our key selling points in attracting tourists down under. We pride ourselves on our clean, green country and its contrast to many other places around the world. Why is it then that in recent decades pride in our The mission of the Chifley Research Centre (CRC) is to natural environment has very rarely translated into champion a Labor culture of ideas. The CRC’s policy action to protect it? work aims to set the groundwork for a fairer and more progressive Australia. Establishing a long-term agenda We have one of the highest rates of fauna extinctions for solving societal problems for progressive ends in the world, globally significant rates of deforestation, is a key aspect of the work undertaken by the CRC. plastics clogging our waterways, and in many regions, The research undertaken by the CRC is designed to diminishing air, water and soil quality threaten human stimulate public policy debate on issues outside of day wellbeing and productivity. -

Markets, Rights and Power in Australian Social Policy Cilities Have Been Sold to Private Organisations), but Other Marketising Instruments Have Been More Common

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship 1 The politics of market encroachment: Policymaker rationales and voter responses Gabrielle Meagher and Shaun Wilson In recent decades, market ideas and practices have increasingly en- croached on activities previously organised by different logics, primar- ily the bureaucratic logic of the public sector and the associational logics of churches and non-government organisations. One highly vis- ible trend has been privatisation of public assets. Universally accessed public utilities in telecommunications, energy and water have been sold off, along with publicly owned financial institutions and transport car- riers. Less visible, but no less important, has been the marketisation of publicly funded social services. The growing use of contracts, com- petition, and quasi-vouchers to allocate funds and service users to the organisations that provide services are examples of this development. Another has been the disproportionate growth of the share of for-profit providers in Australia’s mixed economy of social services. In Australian social policy, market practices and organisations have played an increasingly significant role in shaping the delivery of ser- vices, but in ways that ordinary voters may not identify as connected to ‘privatisation’, understood as asset sales. Asset sales have also taken place in social services (for example, publicly owned residential care fa- Meagher G. & Wilson S. 2015, ‘The politics of market encroachment: policy maker rationales and voter responses’, in Markets, rights and power in Australian social pol- icy, eds G. Meagher & S. Goodwin, Sydney University Press, Sydney. 29 Markets, Rights and Power in Australian Social Policy cilities have been sold to private organisations), but other marketising instruments have been more common. -

An Examination of Australians of Hellenic Descent in the State Parliament of Victoria

LOUCA.qxd 15/1/2001 3:19 ìì Page 115 Louca, Procopis 2003. An Examination of Australians of Hellenic Descent in the State Parliament of Victoria. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and G. Frazis (Eds.) “Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Conference of Greek Studies, Flinders University, September 2001”. Flinders University Department of Languages – Modern Greek: Adelaide, 115-132. An Examination of Australians of Hellenic Descent in the State Parliament of Victoria Procopis Louca Victoria, the second most populated State in Australia, is widely claimed to include as its capital the third largest Grecophone city in the world, after Athens and Thessaloniki. The Victorian State Parliament has more members of Greek and Cypriot (Hellenic) background, than any other jurisdiction in the Commonwealth of Australia. Continuing a series of analyses of the role of elected State and Federal representatives of Hellenic descent in Australia (Louca, 2001), this paper will focus on the Victorian State Parliament, but with reference also to current and former Victorian Federal parliamentarians. There is an exploration of the cultural, political, social and personal influ- ences that guided these individuals to seek election to Parliament and their experiences as politicians with a Hellenic background. As at the beginning of 2002, six sitting members in the Victorian Parliament have a Hellenic background. Four represent the Australian Labor Party (ALP), two the Liberal Party. They are: Alex Andrianopoulos ALP Peter Katsambanis Liberal Nicholas Kotsiras Liberal Jenny Mikakos ALP John Pandazopoulos ALP Theo Theophanous ALP In addition to these current members, there are also two others who have re- tired from Parliament, or are deceased, Theo Sidiropoulos ALP (deceased) 115 Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au LOUCA.qxd 15/1/2001 3:19 ìì Page 116 PROCOPIS LOUCA and Dimitri Dollis ALP (retired). -

Senate Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES Senate Official Hansard No. 3, 2004 TUESDAY, 7 DECEMBER 2004 FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIRST PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2004 Month Date February 10, 11, 12 March 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 22, 23, 24, 25, 29, 30, 31 April 1 May 11, 12, 13 June 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24 August 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 30 November 16, 17, 18, 29, 30 December 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Net- work radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM GOSFORD 98.1 FM BRISBANE 936 AM GOLD COAST 95.7 FM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 747 AM NORTHERN TASMANIA 92.5 FM DARWIN 102.5 FM FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIRST PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency Major-General Michael Jeffery, Companion in the Order of Australia, Com- mander of the Royal Victorian Order, Military Cross Senate Officeholders President—Senator the Hon. Paul Henry Calvert Deputy President and Chairman of Committees—Senator John Joseph Hogg Temporary Chairmen of Committees—Senators the Hon.