A Passion for Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Griffith REVIEW Editon 36: What Is Australia For?

36 A QUARTERLY OF NEW WRITING & IDEAS ESSAYS & MEMOIR, FICTION & REPORTAGE Frank Moorhouse, Kim Mahood, Jim Davidson, Robyn Archer Dennis Altman, Michael Wesley, Nick Bryant, Leah Kaminsky, Romy Ash, David Astle, Some Provocations Peter Mares, Cameron Muir, Bruce Pascoe GriffithREVIEW36 SOME PROVOCATIONS eISBN 978-0-9873135-0-8 Publisher Marilyn McMeniman AM Editor Julianne Schultz AM Deputy Editor Nicholas Bray Production Manager Paul Thwaites Proofreader Alan Vaarwerk Editorial Interns Alecia Wood, Michelle Chitts, Coco McGrath Administration Andrea Huynh GRIFFITH REVIEW South Bank Campus, Griffith University PO Box 3370, South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Ph +617 3735 3071 Fax +617 3735 3272 [email protected] www.griffithreview.com TEXT PUBLISHING Swann House, 22 William St, Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia Ph +613 8610 4500 Fax +613 9629 8621 [email protected] www.textpublishing.com.au SUBSCRIPTIONS Within Australia: 1 year (4 editions) $111.80 RRP, inc. P&H and GST Outside Australia: 1 year (4 editions) A$161.80 RRP, inc. P&H Institutional and bulk rates available on application. COPYRIGHT The copyright of all material published in Griffith REVIEW and on its website remains the property of the author, artist or photographer, and is subject to copyright laws. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. ||| Opinions published in Griffith REVIEW are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, Griffith University or Text Publishing. FEEDBACK AND COMMENT www.griffithreview.com ADVERTISING Each issue of Griffith REVIEW has a circulation of at least 4,000 copies. Full-page adverts are available to selected advertisers. -

Additional Estimates 2010-11

Dinner on the occasion of the First Meeting of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Kirribilli House, Kirribilli, Sydney Sunday, 19 October 2008 Host Mr Francois Heisbourg The Honourable Kevin Rudd MP Commissioner (France) Prime Minister Chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Official Party Security Policy, Special Adviser at the The Honourable Gareth Evans AO QC Foundation pour la Recherche Strategique Co-Chair International Commission on Nuclear Non- General (Ret'd) Jehangir Karamat proliferation and Disarmament Commissioner (Pakistan) and President of the International Crisis Director, Spearhead Research Group Mrs Nilofar Karamat Ms Yoriko Kawaguchi General ((Ret'd) Klaus Naumann Co-Chair Commissioner (Germany) International Commission on Nuclear Non- Member of the International Advisory Board proliferation and Disarmament and member of the World Security Network Foundation of the House of Councillors and Chair of the Liberal Democratic Party Research Dr William Perry Commission on the Environment Commissioner (United States) Professor of Stanford University School of Mr Ali Alatas Engineering and Institute of International Commissioner (Indonesia) Studies Adviser and Special Envoy of the President of the Republic of Indonesia Ambassador Wang Yingfan Mrs Junisa Alatas Commissioner (China) Formerly China's Vice Foreign Minister Dr Alexei Arbatov (1995-2000), China's Ambassador and Commissioner (Russia) Permanent Representative to the United Scholar-in-residence -

Closing State Infrastructure Gaps 4-1

Introduction Rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure Back in the 1960s, California was known for Business leaders echo the public’s concern about 4 more than just Hollywood, The Beach Boys and the widening gap between infrastructure needs beautiful scenery. The state was also famous and current spending. Among surveyed senior for its unparalleled infrastructure. California had business executives, 77 percent believe that the one of the world’s most extensive transportation current level of public infrastructure is inadequate to infrastructure programs in the late 1950s and support their companies’ long-term growth. These early 1960s, which paved the way for much of executives believe that over the next few years, the state’s subsequent economic prosperity. infrastructure will become a more important factor in determining where they locate their operations.65 Those times seem like ancient history in California and throughout America. Today, crowded schools, While there is widespread agreement on the traffic-choked roads, deteriorating bridges, and need to address the growing public infrastructure aged and overused water and sewer treatment deficit, both to create jobs in the short term and facilities undercut the economy’s efficiency and as a prerequisite for enhancing economic develop- erode the quality of American life (see figure 4-1). ment and competitiveness in the longer term, The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) states find themselves in a difficult and precarious estimates that the United States currently only position with respect to how to pay for it. invests about half of what is needed to bring the nation’s infrastructure up to a good condition. -

Political Finance in Australia

Political finance in Australia: A skewed and secret system Prepared by Sally Young and Joo-Cheong Tham for the Democratic Audit of Australia School of Social Sciences The Australian National University Report No.7 Table of contents An immigrant society PAGE ii The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be The Democratic Audit of Australia vii PAGE iii taken to represent the views of either the Democratic Audit of Australia or The Tables iv Australian National University Figures v Abbreviations v © The Australian National University 2006 Executive Summary ix National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data 1 Money, politics and the law: Young, Sally. Questions for Australian democracy Political Joo-Cheong Tham 1 Bibliography 2 Private funding of political parties Political finance in Australia: a skewed and secret system. Joo-Cheong Tham 8 ISBN 0 9775571 0 3 (pbk). 3 Public funding of political parties Sally Young 36 ISBN 0 9775571 1 1 (online). 4 Government and the advantages of office 1. Campaign funds - Australia. I. Tham, Joo-Cheong. II. Sally Young 61 Australian National University. Democratic Audit of 5 Party expenditure Australia. III. Title. (Series: Democratic Audit of Sally Young 90 Australia focussed audit; 7). 6 Questions for reform Joo-Cheong Tham and Sally Young 112 324.780994 7 Conclusion: A skewed and secret system 140 An online version of this paper can be found by going to the Democratic Audit of Australia website at: http://democratic.audit.anu.edu.au References and further -

1.The Indian Administrative Service (Cadre) Rules, 1954

1.THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE (CADRE) RULES, 1954 In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section 1 of Section 3 of the All India Services Act, 1951 (LXI of 1951), the Central Government, after consultation with the Governments of the States concerned, hereby makes the following rules namely:- 1. Short title: - These rules may be called the Indian Administrative Service (Cadre) Rules, 1954. 2. Definitions: - In these rules, unless the context otherwise requires - (a) ‘Cadre officer’ means a member of the Indian Administrative Service; 1(b) ‘Cadre post’ means any of the post specified under item I of each cadre in schedule to the Indian Administrative Service (Fixation of Cadre Strength) Regulations, 1955. (c) ‘State’ means 2[a State specified in the First Schedule to the constitution and includes a Union Territory.] 3(d) ‘State Government concerned’, in relation to a Joint cadre, means the Joint Cadre Authority. 3. Constitution of Cadres - 3(1) There shall be constituted for each State or group of States an Indian Administrative Service Cadre. 3(2) The Cadre so constituted for a State or a group of States is hereinafter referred to as a ‘State Cadre’ or, as the case may be, a ‘Joint Cadre’. 4. Strength of Cadres- 4(1) The strength and composition of each of the cadres constituted under rule 3 shall be determined by regulations made by the Central Government in consultation with the State Governments in this behalf and until such regulations are made, shall be as in force immediately before the commencement of these rules. 4(2) The Central Government shall, 4[ordinarily] at the interval of every 4[five] years, re-examine the strength and composition of each such cadre in consultation with the State Government or the State Governments concerned and may make such alterations therein as it deems fit: Provided that nothing in this sub-rule shall be deemed to affect the power of the Central Government to alter the strength and composition of any cadre at any other time: 1Substituted vide MHA Notification No.14/3/65-AIS(III)-A, dated 05.04.1966. -

Minutes of Proceedings

1 2001 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIFTH ASSEMBLY MONDAY, 12 NOVEMBER 2001 ___________________________ The Legislative Assembly for the Australian Capital Territory convened at 2.00 p.m. in the Legislative Assembly Chamber, Canberra, on Monday, 12 November 2001. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Fifth Assembly for the despatch of business pursuant to a Notice of the Speaker, Mark McRae, Clerk of the Legislative Assembly and Thomas Duncan, Deputy Clerk and Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the Assembly according to their duty, the said Notice was read at the Table by the Clerk: NOTICE CONVENING THE FIRST MEETING OF THE FIFTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Pursuant to subsection 17 (2) of the Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988 (Commonwealth), I, Gregory Gane Cornwell, Speaker of the Legislative Assembly for the Australian Capital Territory, do by this Notice convene the first meeting of the Fifth Legislative Assembly for the Australian Capital Territory at 2.00 p.m. on Monday, 12 November 2001, in the Chamber of the Legislative Assembly, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory. Dated 6 November 2001. GREGORY GANE CORNWELL Speaker, Legislative Assembly for the Australian Capital Territory 2 OATH OR AFFIRMATION OF ALLEGIANCE The Clerk informed the Assembly of the requirements under section 9 of the Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988 and section 6A of the Oaths and Affirmations Act 1984 for Members to make and subscribe an oath and/or affirmation before the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory. -

Dance & Visual Impairment

Dance & Visual Impairment For an Accessibility of Choreographic Practices ANDRÉ FERTIER Cemaforre-European Centre for Cultural Accessibility CENTRE3 NATIONAL DE LA DANSE Dance & Visual Impairment For an Accessibility of Choreographic Practices This digital edition of Dance & Visual Impairment: For an Accessibility of Choreographic Practices was produced in July 2017 by Centre national de la danse and Cemaforre-European Centre for Cultural Accessibility, adapted from Danse & handicap visuel : pour une accessibilité des pratiques chorégraphiques (ISBN : 978-2-914124-50-8 – ISSN: 1621-4153). This book is also available in accessible EPUB3 and DAISY format. CN D is a public institution with an industrial and commercial function funded by the Ministry of Culture. This digital edition was produced as part of the project The Humane Body. The Humane Body is co-funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union. This project was made possible thanks to the collaboration between CN D Centre national de la danse in Pantin and Wiener Tanzwochen/ImPulsTanz in Vienna, Kaaitheater in Brussels, The Place in London. Editorial Board: Patricia Darif (La Possible Échappée), Delphine Demont (Acajou), André Fertier (Cemaforre), Myrha Govindjee (Cemaforre), Brigitte Hyon (CND), Christine Lapoujade (Cemaforre), Florence Lebailly (CND), Amélie Leroy (Cemaforre), Kathy Mépuis (La Possible Échappée), Jonathan Rohman (Cemaforre). Centre national de la danse / www.cnd.fr Chairman of the board of directors: Marie-Vorgan Le Barzic Director and senior editor: -

Talking Tuggeranong with the Chief

Tuggeranong Community Council Newsletter Issue 8: September 2011 Talking Tuggeranong with the Chief Valley. He also conveyed the Council‟s opposition to developments that will in- crease air pollution. He pointed to the proposed industrial expansion at Hume, a planned crematorium and an increase in heavy vehicles on the Monaro High- way as a result of the proposed Can- berra Airport 24 hour freight hub. In regard to the crematorium, Mr. Johns- ton said residents in Fadden and Macar- thur are concerned about emissions from the proposed complex that will be close to their homes. He said the TCC sup- ported a new southern cemetery but has called on the ACT Government to inves- tigate less polluting technologies that achieve the same result. On the question of winter wood smoke pollution, the Chief Minister referred to the latest ACT Government Air Quality Report that showed that, overall, Can- berra enjoyed good air quality. Mr. TCC Vice President, Nick Tsoulias, (Left) and TCC President, Darryl Johnston (Right) following Johnston said while he welcomes the talks with ACT Chief Minister, Katy Gallagher. report it also recognised we still have a major problem with wood smoke pollu- One of the first tasks for re-elected TCC TCC welcomes infrastructure initiatives tion in many Tuggeranong neighbour- President, Darryl Johnston, and newly announced in the last Budget, overall hoods. He said he is also concerned elected TCC Vice President, Nick Tsou- figures suggest more funds are directed about the health impact from neighbour- lias, was to meet with ACT Chief Minis- to other areas of Canberra at the ex- hood wood smoke. -

The Australian Women's Health Movement and Public Policy

Reaching for Health The Australian women’s health movement and public policy Reaching for Health The Australian women’s health movement and public policy Gwendolyn Gray Jamieson Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Gray Jamieson, Gwendolyn. Title: Reaching for health [electronic resource] : the Australian women’s health movement and public policy / Gwendolyn Gray Jamieson. ISBN: 9781921862687 (ebook) 9781921862670 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Birth control--Australia--History. Contraception--Australia--History. Sex discrimination against women--Australia--History. Women’s health services--Australia--History. Women--Health and hygiene--Australia--History. Women--Social conditions--History. Dewey Number: 362.1982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Preface . .vii Acknowledgments . ix Abbreviations . xi Introduction . 1 1 . Concepts, Concerns, Critiques . 23 2 . With Only Their Bare Hands . 57 3 . Infrastructure Expansion: 1980s onwards . 89 4 . Group Proliferation and Formal Networks . 127 5 . Working Together for Health . 155 6 . Women’s Reproductive Rights: Confronting power . 179 7 . Policy Responses: States and Territories . 215 8 . Commonwealth Policy Responses . 245 9 . Explaining Australia’s Policy Responses . 279 10 . A Glass Half Full… . 305 Appendix 1: Time line of key events, 1960–2011 . -

Who's Afraid of Human Rights?

Who’s Afraid of Human Rights? Jon Stanhope Introduction It is my great privilege to talk today about human rights, in our national parliament, and in conjunction with International Human Rights Day. In so doing I want to reinforce the critical importance a commitment to human rights has as the foundation of those core values that characterise our society. I will look at the experience of the operation of the ACT‘s Human Rights Act 2004. And I will suggest there are three paths for us to take to improve human rights of Australians: bold policy ideas, strong political leadership, and more active community engagement. When I talk about human rights, I mean equality and fairness for everyone. A society that commits to human rights, commits to ensuring that everyone is treated with dignity and respect. In Australia, the values that we regard as core to our national character—values such as freedom, respect, fairness, justice, democracy and equality—each stem from a commitment to human rights. They are the values we enshrine in our vernacular as ‗a fair go for all‘. I believe the protection of human rights is everyone‘s responsibility. A shared understanding and respect for human rights provides the foundation for peace, harmony, security and freedom in our community and, importantly, the right for the most vulnerable and marginalised members of our community to have their dignity respected and their basic needs fulfilled. I took, in my decade as chief minister, greatest satisfaction from the way my government implemented social justice, freedom from discrimination, human rights, equality of opportunity, and the rule of law. -

Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia's

PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment This research paper is a project of the Chifley Research Centre, the official think tank of the Australian Labor Party. This paper has been prepared in conjunction with the Labor Environment Action Network (LEAN). The report is not a policy document of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party. Publication details: Wade, Felicity. Gale, Brett. “Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment” Chifley Research Centre, November 2018. PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment FOREWORD Australians are immensely proud of our natural environment. From our golden beaches to our verdant rainforests, Australia seems to be a nation blessed with an abundance of nature’s riches. Our natural environment has played a starring role in Australian movies and books and it is one of our key selling points in attracting tourists down under. We pride ourselves on our clean, green country and its contrast to many other places around the world. Why is it then that in recent decades pride in our The mission of the Chifley Research Centre (CRC) is to natural environment has very rarely translated into champion a Labor culture of ideas. The CRC’s policy action to protect it? work aims to set the groundwork for a fairer and more progressive Australia. Establishing a long-term agenda We have one of the highest rates of fauna extinctions for solving societal problems for progressive ends in the world, globally significant rates of deforestation, is a key aspect of the work undertaken by the CRC. plastics clogging our waterways, and in many regions, The research undertaken by the CRC is designed to diminishing air, water and soil quality threaten human stimulate public policy debate on issues outside of day wellbeing and productivity. -

Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change

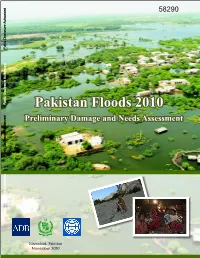

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Title and back page photos by Gerhard Juren and M. Ismail Khan Pakistan Floods 2010 Preliminary Damage and Needs Assessment Preliminary Damage and Needs Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary . .13 Disaster Overview . .13 About the Damage and Needs Assessment . .13 Report Overview . .15 Summary Table of Total Damage and Reconstruction Needs . .15 A. Background of the 2010 Floods . .19 Overview . .19 National Response . .20 Civil Society and Private Sector Response . .20 International Donor Response . .20 B. Pakistan’s social and economic context . .21 Political and Social Context . .21 Economic Framework . .22 C. Damage and Needs Assessment Approach and Methodology . .22 Build Back Smarter (BBS) . .22 Data Collection . .23 Damage Quantification . .23 Validation . .23 D. Economic Impact . .24 E. Summary of Damage and Needs by sector . .26 Housing . .26 Health . .27 Education . .28 Irrigation and Flood Protection . .28 Transport and Communications . .29 Water Supply and Sanitation . .29 Energy . .30 Agriculture, Livestock & Fisheries . .31 Private Sector & Industries . .31 Financial Sector . .32 Social Protection and Livelihoods . .33 Governance . .33 Environment . .33 F. Guiding Principles of the Needs Assessment and Recovery Strategy . .34 G. Governance and Institutional Considerations . .36 Institutional Framework . .36 Outline Institutional Structure . .38 Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) System . .39 Pakistan Floods 2010 H. Social Aspects . .40 I. Environmental Aspects . .42 Environmental and Social Safeguards . .42 J. Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change . .43 Pakistan Disaster Risk Profile and the Current Flood Event . .43 Key Lessons Learnt from Flood Response 2010 . .43 Climate Change and Flood Linkages . .43 Institutional Structure, Legal and Policy Framework for Disaster Management .