Accepted Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Misconduct: the Case for a Federal Icac

MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS A HISTORY OF MISCONDUCT: THE CASE FOR A FEDERAL ICAC INDEPENDENT JO URNALISTS MICH AEL WES T A ND CALLUM F OOTE, COMMISSIONED B Y G ETUP 1 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS MISCONDUCT IN RESOURCES, WATER AND LAND MANAGEMENT Page 5 MISCONDUCT RELATED TO UNDISCLOSED CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Page 8 POTENTIAL MISCONDUCT IN LOBBYING MISCONDUCT ACTIVITIES RELATED TO Page 11 INAPPROPRIATE USE OF TRANSPORT Page 13 POLITICAL DONATION SCANDALS Page 14 FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON THE POLITICAL PROCESS Page 16 ALLEGEDLY FRAUDULENT PRACTICES Page 17 CURRENT CORRUPTION WATCHDOG PROPOSALS Page 20 2 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS FOREWORD: Trust in government has never been so low. This crisis in public confidence is driven by the widespread perception that politics is corrupt and politicians and public servants have failed to be held accountable. This report identifies the political scandals of the and other misuse of public money involving last six years and the failure of our elected leaders government grants. At the direction of a minister, to properly investigate this misconduct. public money was targeted at voters in marginal electorates just before a Federal Election, In 1984, customs officers discovered a teddy bear potentially affecting the course of government in in the luggage of Federal Government minister Australia. Mick Young and his wife. It had not been declared on the Minister’s customs declaration. Young This cheating on an industrial scale reflects a stepped aside as a minister while an investigation political culture which is evolving dangerously. into the “Paddington Bear Affair” took place. The weapons of the state are deployed against journalists reporting on politics, and whistleblowers That was during the prime ministership of Bob in the public service - while at the same time we Hawke. -

Budget Estimates 2011-12

Senate Standing Committee on Economics ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Innovation, Industry, Science and Research Portfolio Budget Estimates Hearing 2011-12 30 May 2011 AGENCY/DEPARTMENT: INNOVATION, INDUSTRY, SCIENCE AND RESEARCH TOPIC: PMSEIC REFERENCE: Written Question – Senator Colbeck QUESTION No.: BI-132 Senator COLBECK: Is a list of attendees documented for each of the PMSEIC meetings? If so, could these lists be provided for each of the meetings of 23 April 2008, 9 October 2008, 5 June 2009, 18 March 2010 and 4 February 2011? Alternatively, could you please provide a full breakdown of which Departmental secretaries have attended each of these meetings respectively? ANSWER Yes, full lists of attendees are documented for each of the PMSEIC meetings. -

City of Palmerston

CITY OF PALMERSTON Notice of Council Meeting To be held in Council Chambers Civic Plaza, Palmerston Ricki Bruhn on Tuesday 4 April 2017 at 6.30pm. Chief Executive Officer Any member of Council who may have a conflict of interest, or a possible conflict of interest in regard to any item of business to be discussed at a Council meeting or a Committee meeting should declare that conflict of interest to enable Council to manage the conflict and resolve it in accordance with its obligations under the Local Government Act and its policies regarding the same. Audio Disclaimer An audio recording of this meeting is being made for minute taking purposes as authorised by City of Palmerston Policy MEE3 Recording of Meetings, available on Council’s Website. Acknowledgement of Traditional Ownership I respectfully acknowledge the past and present Traditional Custodians of this land on which we are meeting, the Larrakia people. It is a privilege to be standing on Larrakia country. 1 PRESENT 2 APOLOGIES Alderman Bunker – Leave of Absence ACCEPTANCE OF APOLOGIES AND LEAVE OF ABSENCE 3 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES RECOMMENDATION 1. THAT the minutes of the Council Meeting held Tuesday, 21 March 2017 pages 9031 to 9088, be confirmed. 2. THAT the Confidential minutes of the Council Meeting held Tuesday, 21 March 2017 page 291 to 292, be confirmed. 3. THAT the minutes of the Special Council Meeting held Tuesday, 28 March 2017 pages 9089 to 9091, be confirmed. 4. THAT the confidential minutes of the Special Council Meeting held Tuesday, 28 March 2017 pages 293 to 294, be confirmed. -

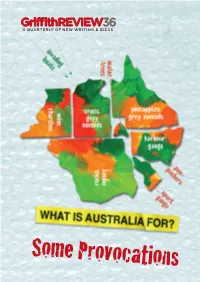

Griffith REVIEW Editon 36: What Is Australia For?

36 A QUARTERLY OF NEW WRITING & IDEAS ESSAYS & MEMOIR, FICTION & REPORTAGE Frank Moorhouse, Kim Mahood, Jim Davidson, Robyn Archer Dennis Altman, Michael Wesley, Nick Bryant, Leah Kaminsky, Romy Ash, David Astle, Some Provocations Peter Mares, Cameron Muir, Bruce Pascoe GriffithREVIEW36 SOME PROVOCATIONS eISBN 978-0-9873135-0-8 Publisher Marilyn McMeniman AM Editor Julianne Schultz AM Deputy Editor Nicholas Bray Production Manager Paul Thwaites Proofreader Alan Vaarwerk Editorial Interns Alecia Wood, Michelle Chitts, Coco McGrath Administration Andrea Huynh GRIFFITH REVIEW South Bank Campus, Griffith University PO Box 3370, South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Ph +617 3735 3071 Fax +617 3735 3272 [email protected] www.griffithreview.com TEXT PUBLISHING Swann House, 22 William St, Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia Ph +613 8610 4500 Fax +613 9629 8621 [email protected] www.textpublishing.com.au SUBSCRIPTIONS Within Australia: 1 year (4 editions) $111.80 RRP, inc. P&H and GST Outside Australia: 1 year (4 editions) A$161.80 RRP, inc. P&H Institutional and bulk rates available on application. COPYRIGHT The copyright of all material published in Griffith REVIEW and on its website remains the property of the author, artist or photographer, and is subject to copyright laws. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. ||| Opinions published in Griffith REVIEW are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, Griffith University or Text Publishing. FEEDBACK AND COMMENT www.griffithreview.com ADVERTISING Each issue of Griffith REVIEW has a circulation of at least 4,000 copies. Full-page adverts are available to selected advertisers. -

Political Finance in Australia

Political finance in Australia: A skewed and secret system Prepared by Sally Young and Joo-Cheong Tham for the Democratic Audit of Australia School of Social Sciences The Australian National University Report No.7 Table of contents An immigrant society PAGE ii The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be The Democratic Audit of Australia vii PAGE iii taken to represent the views of either the Democratic Audit of Australia or The Tables iv Australian National University Figures v Abbreviations v © The Australian National University 2006 Executive Summary ix National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data 1 Money, politics and the law: Young, Sally. Questions for Australian democracy Political Joo-Cheong Tham 1 Bibliography 2 Private funding of political parties Political finance in Australia: a skewed and secret system. Joo-Cheong Tham 8 ISBN 0 9775571 0 3 (pbk). 3 Public funding of political parties Sally Young 36 ISBN 0 9775571 1 1 (online). 4 Government and the advantages of office 1. Campaign funds - Australia. I. Tham, Joo-Cheong. II. Sally Young 61 Australian National University. Democratic Audit of 5 Party expenditure Australia. III. Title. (Series: Democratic Audit of Sally Young 90 Australia focussed audit; 7). 6 Questions for reform Joo-Cheong Tham and Sally Young 112 324.780994 7 Conclusion: A skewed and secret system 140 An online version of this paper can be found by going to the Democratic Audit of Australia website at: http://democratic.audit.anu.edu.au References and further -

Ministry List As at 19 March 2014

Commonwealth Government TURNBULL MINISTRY 19 July 2016 TITLE MINISTER Prime Minister The Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP Minister for Indigenous Affairs Senator the Hon Nigel Scullion Minister for Women Senator the Hon Michaelia Cash Cabinet Secretary Senator the Hon Arthur Sinodinos AO Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for the Public Service Senator the Hon Michaelia Cash Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Counter-Terrorism The Hon Michael Keenan MP Minister Assisting the Cabinet Secretary Senator the Hon Scott Ryan Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Cyber Security The Hon Dan Tehan MP Assistant Minister to the Prime Minister Senator the Hon James McGrath Assistant Minister for Cities and Digital Transformation The Hon Angus Taylor MP Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources The Hon Barnaby Joyce MP Assistant Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources Senator the Hon Anne Ruston Assistant Minister to the Deputy Prime Minister The Hon Luke Hartsuyker MP Minister for Foreign Affairs The Hon Julie Bishop MP Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment The Hon Steven Ciobo MP Minister for International Development and the Pacific Senator the Hon Concetta Fierravanti-Wells Assistant Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment The Hon Keith Pitt MP Attorney-General Senator the Hon George Brandis QC (Vice-President of the Executive Council) (Leader of the Government in the Senate) Minister for Justice The Hon Michael Keenan MP Treasurer The Hon Scott Morrison MP Minister for Revenue and Financial Services -

Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45Th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief Lists

Barton Deakin Brief: Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief lists individuals and institutions on Twitter relevant to policy and political developments in the federal government domain. These institutions and individuals either break policy-political news or contribute in some form to “the conversation” at national level. Being on this list does not, of course, imply endorsement from Barton Deakin. This Brief is organised by categories that correspond generally to portfolio areas, followed by categories such as media, industry groups and political/policy commentators. This is a “living” document, and will be amended online to ensure ongoing relevance. We recognise that we will have missed relevant entities, so suggestions for inclusions are welcome, and will be assessed for suitability. How to use: If you are a Twitter user, you can either click on the link to take you to the author’s Twitter page (where you can choose to Follow), or if you would like to follow multiple people in a category you can click on the category “List”, and then click “Subscribe” to import that list as a whole. If you are not a Twitter user, you can still observe an author’s Tweets by simply clicking the link on this page. To jump a particular List, click the link in the Table of Contents. Barton Deakin Pty. Ltd. Suite 17, Level 2, 16 National Cct, Barton, ACT, 2600. T: +61 2 6108 4535 www.bartondeakin.com ACN 140 067 287. An STW Group Company. SYDNEY/MELBOURNE/CANBERRA/BRISBANE/PERTH/WELLINGTON/HOBART/DARWIN -

Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia's

PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment This research paper is a project of the Chifley Research Centre, the official think tank of the Australian Labor Party. This paper has been prepared in conjunction with the Labor Environment Action Network (LEAN). The report is not a policy document of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party. Publication details: Wade, Felicity. Gale, Brett. “Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment” Chifley Research Centre, November 2018. PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment FOREWORD Australians are immensely proud of our natural environment. From our golden beaches to our verdant rainforests, Australia seems to be a nation blessed with an abundance of nature’s riches. Our natural environment has played a starring role in Australian movies and books and it is one of our key selling points in attracting tourists down under. We pride ourselves on our clean, green country and its contrast to many other places around the world. Why is it then that in recent decades pride in our The mission of the Chifley Research Centre (CRC) is to natural environment has very rarely translated into champion a Labor culture of ideas. The CRC’s policy action to protect it? work aims to set the groundwork for a fairer and more progressive Australia. Establishing a long-term agenda We have one of the highest rates of fauna extinctions for solving societal problems for progressive ends in the world, globally significant rates of deforestation, is a key aspect of the work undertaken by the CRC. plastics clogging our waterways, and in many regions, The research undertaken by the CRC is designed to diminishing air, water and soil quality threaten human stimulate public policy debate on issues outside of day wellbeing and productivity. -

Terry Mccrann: Which Is It Labor … Are We in Recession Or Can We Afford Higher Power Prices? Terry Mccrann, Herald Sun, March 11, 2019 8:00Pm Subscriber Only

Terry McCrann: Which is it Labor … are we in recession or can we afford higher power prices? Terry McCrann, Herald Sun, March 11, 2019 8:00pm Subscriber only Labor’s top duo Bill Shorten and Chris Bowen want to have it both ways. On the one hand, they say the economy is in deep trouble — indeed, that it has actually already slid into recession, according to Bowen, in “per capita” (per person) terms. MORE MCCRANN: WHY BOWEN’S RECESSION CALL IS RUBBISH JAMES CAMPBELL: SCOMO IS ROLLING THE DICE ON BOATS Yet on the other, that households — and even more, small and medium-sized businesses — who are already paying cripplingly high gas and electricity prices, are actually in such great financial shape that they can happily pay higher and higher prices yet. And further, that an incoming Labor government can hit investors with over $200 billion of new taxes and the economy will just keep riding smoothly on. Shadow treasurer Chris Bowen says Australia is already in a “per capita” recession. At least they can’t be accused of hiding any of this. The disastrous economic managers they promise to be — especially Bowen who is on the record as thinking Wayne Swan was one of Australia’s greatest treasurers — is ‘hiding’ not just in plain sight, but in right-in-your face sight. The so-called “per capita recession” that Bowen came out with last week was just rubbish. Yes, the economy slowed in the second half of last year. In the first half, GDP — the measure of Australia’s economic output — was growing at close to a 4 per cent annual rate. -

Trends in Australian Political Opinion Results from the Australian Election Study 1987– 2019

Trends in Australian Political Opinion Results from the Australian Election Study 1987– 2019 Sarah Cameron & Ian McAllister School of Politics & International Relations ANU College of Arts & Social Sciences australianelectionstudy.org Trends in Australian Political Opinion Results from the Australian Election Study 1987– 2019 Sarah Cameron Ian McAllister December, 2019 Sarah Cameron School of Social and Political Sciences The University of Sydney E [email protected] Ian McAllister School of Politics and International Relations The Australian National University E [email protected] Contents Introduction 5 The election campaign 7 Voting and partisanship 17 Election issues 31 The economy 51 Politics and political parties 71 The left-right dimension 81 The political leaders 85 Democracy and institutions 97 Trade unions, business and wealth 107 Social issues 115 Defence and foreign affairs 129 References 143 Appendix: Methodology 147 Introduction The Liberal-National Coalition The results also highlight how In 2019 two further surveys are win in the 2019 Australian federal voter attitudes contributed available to complement the election came as a surprise to the to the election result. Factors AES. The first is Module 5 of the nation. The media and the polls advantaging the Coalition in the Comparative Study of Electoral australianelectionstudy.org had provided a consistent narrative 2019 election include: the focus Systems project (www.cses. in the lead up to election day that on economic issues (p. 32), an org). This survey used the Social > Access complete data files and Labor was headed for victory. area in which the Coalition has Research Centre’s ‘Life in Australia’ documentation to conduct your When we have unexpected election a strong advantage over Labor panel and was fielded just after the own analysis results, how do we make sense of (p. -

Corona GOVERNANCE

CORONA STIMULUS & RECOVERY © SERIES REPORT # 2 N A T I O N A L G O V E R N A N C E E F F E C T I V E N E S S in line with ACCEPTED BUDGETTING, PLANNING & ENGAGEMENT PROTOCOLS ROBERT GIBBONS 18 NOVEMBER 2020 © see copyright statement on last page INTRODUCTION Bubonic Plague hit Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne in 1900 and the Sydney response was the world’s most famous, the “social laboratory of the world”. Governance was key to that response, medicine was supportive. 120 years later the Novel Coronavirus thence COVID-19 was mayhem, warnings had been ignored and Australia was sliding backwards economically. There is supposed to be a self-correcting mechanism called “budget repair” when a government finds it mismanaged bushfires and rorts so that the next one would be better planned and organised. The opposite happened, repair (MYEFO) was cancelled, delays became critical, mistakes abounded as the “Canberra Bubble” did not know how to prepare a “plan” as I had done in 2 days when BHP announced the closure of steelmaking in Newcastle in 1997. The States pushed PM Morrison into setting up a cooperative National Cabinet on 13 March 2020. It emerged from the Canberra Bubble without any explanation of logic, objectives, modus operandi or budget, and this analyst predicted it would fail as soon as a member’s self-interest clashed with the collective view – and that was a safe bet as NSW’s Premier, Glady Berejiklian, is an habitual renegade and regularly attacks her peers. It has been under the control of the PM’s department head who has a NSW reputation for negative practices (he used to report to Berejiklian). -

![Re Canavan, Re Ludlam, Re Waters, Re Roberts [No 2], Re Joyce, Re Nash, Re Xenophon (2017) 349 Alr 534](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0915/re-canavan-re-ludlam-re-waters-re-roberts-no-2-re-joyce-re-nash-re-xenophon-2017-349-alr-534-1610915.webp)

Re Canavan, Re Ludlam, Re Waters, Re Roberts [No 2], Re Joyce, Re Nash, Re Xenophon (2017) 349 Alr 534

Kyriaco Nikias* DUAL CITIZENS IN THE FEDERAL PARLIAMENT: RE CANAVAN, RE LUDLAM, RE WATERS, RE ROBERTS [NO 2], RE JOYCE, RE NASH, RE XENOPHON (2017) 349 ALR 534 ‘where ignorance is bliss, ‘Tis folly to be wise.’1 I INTRODUCTION n mid-2017, it emerged that several Federal parliamentarians may have been ineligible to be elected on account of their dual citizenship status by operation of Is 44(i) of the Constitution. In Re Canavan,2 the High Court, sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns, found five of them ineligible. This case note interrogates the Court’s interpretation of s 44(i), and analyses the judgment with reference to its political context and its constitutional significance. It is argued that the Court has left unclear the question of how it will treat foreign law in respect of s 44(i), and that the problems which this case has highlighted might only be resolved by constitutional reform. II THE POLITICAL CONTEXT A Background In July 2017, two Greens senators, Scott Ludlam and Larissa Waters, resigned from the Senate, upon announcing that they were, respectively, New Zealand and Canadian citizens. Politicians soon traded blows. The Prime Minister accused the Greens of ‘careless[ness]’ with respect to their eligibility for nomination.3 But soon * Student Editor, Adelaide Law Review, University of Adelaide. 1 Thomas Gray, ‘Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College’ in D C Tovey (ed), Gray’s English Poems (Cambridge University Press, first published 1898, 2014 ed) 4, 7, lines 99–100. 2 Re Canavan, Re Ludlam, Re Waters, Re Roberts [No 2], Re Joyce, Re Nash, Re Xenophon (2017) 349 ALR 534 (‘Re Canavan’).