Politics, Policy and Public Administration in Theory and Practice Essays in Honour of Professor John Wanna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V. J. Carroll and the Essence of Journalism the Oldest Rule Of

V. J. Carroll and the essence of journalism The oldest rule of journalism – and the most forgotten – is to tell the customers what is really going on - Stanley Cecil (Sol) Chandler. Monday 22 April 2013: to Macquarie University with Max Suich to observe the installation of Vic (The Sorcerer) Carroll, as Doctor of Letters (honoris causa). In his address to graduates, Dr Carroll said: “That CV the vice chancellor just read to you in no way prepared me for how to respond to the letter I received from him last November telling me that the University Council had decided to confer on me a Doctor of Letters honoris causa in recognition of my contributions to journalism. “I have been ever conscious of what journalism has done for me in providing me with a living wage for an important phase of my life and particularly for driving my continuing education for the last 60 years. But what I had done for journalism? “That was a foreign country I had not risked exploring. Fortunately, help was at hand. I had been reading a review of a new book containing letters written around 1903 by the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke [1875-1926]. “Rilke had gone to Paris to soak up the culture and write about the sculptor [Auguste] Rodin [1840-1917]. Rilke was shocked. Rodin didn’t wait around for inspiration. Rodin worked all the time. And he worked on the special thing that he saw in everything. Rilke got the message. Der Ding, the Thing, to be observed in everything, was paramount.” Michael Egan, Chancellor of Macquarie University, and Honorary Doctor Victor Carroll. -

Parliamentary Library Wa

Premiers of Western Australia PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY WA PREMIERS OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA The Fast Facts on the Premiers of Western Australia THE FIRST PREMIER THE LONGEST THE ONLY PREMIER THEOFTHE FIRST WESTERN FIRST PREMIER PREMIER OF PREMIERSHIP IS HELD BY TO DIE IN OFFICE IN AUSTRALIAWESTERNOF WESTERN AUSTRALIA WAS SIR SIR DAVID BRAND WHO WA WAS GEORGE JOHNWASAUSTRALIA SIRFORREST JOHN FORRESTINWAS 1890 SIR. SERVED FOR 11 YEARS: LEAKE. HE DIED OF JOHN FORRESTIN 1890. IN 1890. 2 APRIL 1959 - 3 MARCH PNEUMONIA ON 24 1971 JUNE 1902. THE YOUNGEST THE SHORTEST WA PREMIER IN WA WAS PREMIERSHIP IS HELD JOHN SCADDAN AGED 35 BY HAL COLEBATCH YEARS WHO HELD OFFICE WHO SERVED FOR ONE BETWEEN 1911 AND 1914. CALENDAR MONTH IN 1919. THE ONLY PREMIER TO HE WAS ALSO THE ALSO BE A GOVERNOR OF ONLY PREMIER WHO WESTERN AUSTRALIA WAS A MEMBER OF WAS SIR JAMES MITCHELL. THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL. THE LONGEST WA THE OLDEST PREMIERSHIP IS HELD BY PREMIER IN WA WHEN SIR DAVID BRAND WHO SWORN IN WAS JOHN SERVED FOR 11 YEARS IN TONKIN AGED 69 YEARS 1971. IN 1971. THE ONLY FATHER THE FIRST WOMAN AND SON PREMIERS IN PREMIER IN WA AND WA WERE SIR CHARLES AUSTRALIA WAS COURT AND RICHARD CARMEN LAWRENCE COURT. FROM 1990 TO 1993. November 5, 2013 History Notes: Premiers of Western Australia Premiers of Western Australia “COURTESY TITLE” Premier’s Role: ‘first among equals’ When Western Australia first commenced responsible The Premier is the Head of Government of the State in Western government in 1890 the word Australia with executive power that is subject to the advice of the premier was merely a courtesy Cabinet. -

Fabian Society

SOS POLITICAL SCIENCE & PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE II SEM POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY: MODERN POLITICAL THOUGHT, THEORY & CONTEMPORARY IDEOLOGIES UNIT-III Topic Name-fabian socialism WHAT IS MEANT BY FABIAN SOCIALISM? • The Fabian Society is a British socialistorganisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow WHO STARTED THE FABIAN SOCIETY? • Its nine founding members were Frank Podmore, Edward R. Pease, William Clarke, Hubert Bland, Percival Chubb, Frederick Keddell, H. H. Champion, Edith Nesbit, and Rosamund Dale Owen. WHO IS THE PROPOUNDER OF FABIAN SOCIALISM? • In the period between the two World Wars, the "Second Generation" Fabians, including the writers R. H. Tawney, G. D. H. Cole and Harold Laski, continued to be a major influence on socialistthought. But the general idea is that each man should have power according to his knowledge and capacity. WHAT IS THE FABIAN POLICY? • The Fabian strategy is a military strategy where pitched battles and frontal assaults are avoided in favor of wearing down an opponent through a war of attrition and indirection. While avoiding decisive battles, the side employing this strategy harasses its enemy through skirmishes to cause attrition, disrupt supply and affect morale. Employment of this strategy implies that the side adopting this strategy believes time is on its side, but it may also be adopted when no feasible alternative strategy can be devised. HISTORY • This -

Imagereal Capture

TWO NATIONS, TWO DESTINIES: A REFLECTION ON THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE WESTERNAUSTRALLAN SECESSION MOVEMENT TO AUSTRALIA, CANADAAND THE BRITISH EMPIRE CHRISTOPHER W BESANT* Society is indeed a contract. Subordinate contracts for objects of mere occa- sional interest may be dissolved at pleasure - but the state ought not to be considered as nothing better than a partnership agreement in a trade of pepper and coffee, callico or tobacco, or some other such low concern, to be taken up for a little temporary interest, and to be dissolved by the fancy of the parties. It is to be looked on with other reverence; because it is not a partnership in things subservient only to the gross animal existence of a temporary and perishable nature. It is a partnership in all science; a partnership in all art; a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection. As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born. Each contract of each particular state is but a clause in the great primaeval contract of eternal society .... The municipal corporations of that universal kingdom are not morally at liberty at their pleasure, and on their speculations of a contingent improvement, wholly to separate and tear asunder the bands of their suboldinate community ....I Burke in Reflections on the Revolution in France * BA (McMast) ARCT LLB (Toronto) LLM (Cantab). Visiting Lecturer in Law, University of Western Australia. -

Some Aspects of the Federal Political Career of Andrew Fisher

SOME ASPECTS OF THE FEDERAL POLITICAL CAREER OF ANDREW FISHER By EDWARD WIL.LIAM I-IUMPHREYS, B.A. Hans. MASTER OF ARTS Department of History I Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degr'ee of Masters of Arts (by Thesis only) JulV 2005 ABSTRACT Andrew Fisher was prime minister of Australia three times. During his second ministry (1910-1913) he headed a government that was, until the 1940s, Australia's most reformist government. Fisher's second government controlled both Houses; it was the first effective Labor administration in the history of the Commonwealth. In the three years, 113 Acts were placed on the statute books changing the future pattern of the Commonwealth. Despite the volume of legislation and changes in the political life of Australia during his ministry, there is no definitive full-scale biographical published work on Andrew Fisher. There are only limited articles upon his federal political career. Until the 1960s most historians considered Fisher a bit-player, a second ranker whose main quality was his moderating influence upon the Caucus and Labor ministry. Few historians have discussed Fisher's role in the Dreadnought scare of 1909, nor the background to his attempts to change the Constitution in order to correct the considered deficiencies in the original drafting. This thesis will attempt to redress these omissions from historical scholarship Firstly, it investigates Fisher's reaction to the Dreadnought scare in 1909 and the reasons for his refusal to agree to the financing of the Australian navy by overseas borrowing. -

Centenary of Canberra Reaching out Wrap-Up

CANBERRA100.COM.AU REACHING OUT ACT FRINGES This is one of a series of UNMADE EDGES- five Centenary of Canberra DISTINCTIVE publications which capture PLACES the essence of the year-long The stories of Tharwa, Hall, Oaks Estate, Pialligo, Uriarra and Stromlo inspired a series of art projects culminating in installations, celebration exhibitions, art workshops and storytelling. IMAGE: DAVID WONG Uriarra “One of the great achievements of Dan Stewart-Moore’s new sculpture Loop was designed to be assembled the Centenary of Canberra, in my by the community. Made from pine, historically significant to the area, mind, has been the unearthing of ARTWORK BY CAROLYN YOUNG the 100 pieces represent the 100 community and city pride. This is blocks in Uriarra. something we must carry forward as “By continuing to bring a legacy—the means to a permanent Hall the residents together Intimate engagements with in this way we are able departure from Canberra bashing artworks, including performance and to celebrate the strong photography which responded to the and self-deprecation about our city. rich history, natural resources and community bonds A city brand is far more than a logo. culture of the Hall village and that residents of this its community. wonderful place have It’s a collective idea—and a collective This event showcased photomedia maintained for more advocacy—about who we are and artists John Reid, Carolyn Young, than 85 years” Kevin Miller and Marzena Wasikowska; what we have to offer” and sculptors Amanda Stuart and IMAGE: BROOKE SMALL Jess Agnew, resident Heike Qualitz. Chief Minister Katy Gallagher, 2013 Blackfriars Stromlo Lecture at the Australian Catholic University “An inspired project and a great Artists Dan Maginnity and Hana Hoyne ran a series of workshops in response from the Stromlo Settlement to construct chairs, “When we devise and launch a Hall contingent. -

Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915

5 Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915. Andrew Fisher became the 5th prime minister when the Liberal- Labor coalition government headed by Alfred Deakin collapsed due to loss of parliamentary Labor support. Fisher’s first period as prime minister ended when the new Fusion Party of Deakin and Joseph Cook defeated the government in parliament. His second term resulted from an overwhelming Labor victory at elections in 1910. However, Labor lost power by one seat at the 1913 elections. Fisher was prime minister again in 1914, as a result of a double-dissolution election. Fisher resigned from office in October 1915, his health affected by the pressures of political life. Member of the Australian Labor Party c1901-28. Member of the House of Representatives for the seat of Wide Bay (Queensland) 1901-15; Minister for Trade and Customs 1904; Treasurer 1908-09, 1910-13, 1914-15. Main achievements (1904-1915) Under his prime ministership, the Commonwealth Government issued its first currency which replaced bank and State currency as the only legal tender. Also, the Commonwealth Bank was established. Strengthened the Conciliation and Arbitration Act. Introduced a progressive land tax on unimproved properties. Construction began on the trans-Australian railway, linking Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie. Established the Australian Capital Territory and brought the Northern Territory under Commonwealth control. Established the Royal Australian Navy. Improved access to invalid and aged pensions and brought in maternity allowances. Introduced workers’ compensation for federal public servants. -

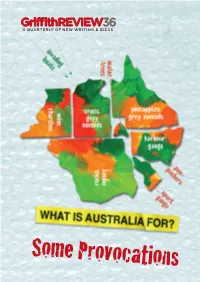

Griffith REVIEW Editon 36: What Is Australia For?

36 A QUARTERLY OF NEW WRITING & IDEAS ESSAYS & MEMOIR, FICTION & REPORTAGE Frank Moorhouse, Kim Mahood, Jim Davidson, Robyn Archer Dennis Altman, Michael Wesley, Nick Bryant, Leah Kaminsky, Romy Ash, David Astle, Some Provocations Peter Mares, Cameron Muir, Bruce Pascoe GriffithREVIEW36 SOME PROVOCATIONS eISBN 978-0-9873135-0-8 Publisher Marilyn McMeniman AM Editor Julianne Schultz AM Deputy Editor Nicholas Bray Production Manager Paul Thwaites Proofreader Alan Vaarwerk Editorial Interns Alecia Wood, Michelle Chitts, Coco McGrath Administration Andrea Huynh GRIFFITH REVIEW South Bank Campus, Griffith University PO Box 3370, South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Ph +617 3735 3071 Fax +617 3735 3272 [email protected] www.griffithreview.com TEXT PUBLISHING Swann House, 22 William St, Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia Ph +613 8610 4500 Fax +613 9629 8621 [email protected] www.textpublishing.com.au SUBSCRIPTIONS Within Australia: 1 year (4 editions) $111.80 RRP, inc. P&H and GST Outside Australia: 1 year (4 editions) A$161.80 RRP, inc. P&H Institutional and bulk rates available on application. COPYRIGHT The copyright of all material published in Griffith REVIEW and on its website remains the property of the author, artist or photographer, and is subject to copyright laws. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. ||| Opinions published in Griffith REVIEW are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, Griffith University or Text Publishing. FEEDBACK AND COMMENT www.griffithreview.com ADVERTISING Each issue of Griffith REVIEW has a circulation of at least 4,000 copies. Full-page adverts are available to selected advertisers. -

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution Or Black Hole?

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Author Tiernan, Anne-Maree Published 2005 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Department of Politics and Public Policy DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3587 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367746 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Ministerial Staff under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Anne-Maree Tiernan BA (Australian National University) BComm (Hons) (Griffith University) Department of Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2004 Abstract This thesis traces the development of the ministerial staffing system in Australian Commonwealth government from 1972 to the present. It explores four aspects of its contemporary operations that are potentially problematic. These are: the accountability of ministerial staff, their conduct and behaviour, the adequacy of current arrangements for managing and controlling the staff, and their fit within a Westminster-style political system. In the thirty years since its formal introduction by the Whitlam government, the ministerial staffing system has evolved to become a powerful new political institution within the Australian core executive. Its growing importance is reflected in the significant growth in ministerial staff numbers, in their increasing seniority and status, and in the progressive expansion of their role and influence. There is now broad acceptance that ministerial staff play necessary and legitimate roles, assisting overloaded ministers to cope with the unrelenting demands of their jobs. However, recent controversies involving ministerial staff indicate that concerns persist about their accountability, about their role and conduct, and about their impact on the system of advice and support to ministers and prime ministers. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction Tuesday 19th February 2019 at 10.00 Viewing: For enquiries relating to the auction Monday 18th February 2019 10:00 - 16:00 please contact: 09:00 morning of auction Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One 81 Greenham Business Park NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment Music www.specialauctionservices.com As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indications of the provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. ORDER OF AUCTION Music Hall & other Disc Records 1-68 Cylinder Records 69-108 Phonographs & Gramophones 109-149 Technical Apparatus 150-155 Musical Boxes 156-171 Jazz/ other 78s 172-184 Vinyl Records 185-549 Reel to Reel Tapes 550-556 CDs/ CD Box Sets 557-604 DVDs 605-612 Music Memorabilia 613-658 Music Posters 659-666 Film & Entertainment Memorabilia Including items from the Estate of John Inman 667-718 Film Posters 719-743 Musical Instruments 744-759 Hi-Fi 760-786 2 www.specialauctionservices.com MUSIC HALL & OTHER DISC RECORDS 18. Music hall and similar records, 10 inch, 67, by Geo Robey (G & T 2-2721 & 18 1. -

Limp Election Campaign Launch Does Anna Bligh No Favours

Limp election campaign launch does Anna Bligh no favours • by:Steven Wardill • From:The Courier-Mail • February 20, 2012 12:01AM Yet the backdrop for Anna Bligh's first campaign contribution after her scheduled trip to see the Governor actually demonstrated Labor's weaknesses as much, if not more, than its strengths. The location was Ashgrove State School, where the "Keep Kate" team were blowing up balloons and painting signage in the pink hue Labor incumbent Kate Jones has chosen for her campaign. Labor's aim was to keep the Ashgrove electorate firmly in the forefront of voter's minds as the campaign for the March 24 election began in earnest. They wanted to sow seeds of doubt about the LNP's leadership by demonstrating just how hard they were fighting to retain the inner-western Brisbane seat. The aim was to continue pushing the issue of what happens in the event that the LNP wins but leader Campbell Newman loses Ashgrove. However, the Ashgrove campaign is also a graphic demonstration of the problem Labor has at this election. Jones is campaigning as "a local girl made good", not as a member of the Bligh Government. The Labor brand and Bligh herself are all but invisible amid the pink propaganda. This is not a campaign about winning an election with a positive agenda and a united team. It is about an individual candidate trying to separate herself from the baggage of her political brand. The contrast with Newman's launch could not have been more stark. He appeared at a golf club just a few kilometres away, with LNP candidates used as living cardboard cutouts behind the cameras. -

The Queensland Election 2012: a Voters’ Firestorm

THE QUEENSLAND ELECTION 2012: A VOTERS’ FIRESTORM I. BACKGROUND & ANALYSIS The official Latin Motto for the State of Queensland is “Audax At Fidelis”, translated as “Bold But Faithful.” Both concepts were severely tested and sharply called into question by the historic and devastating result of the 2012 Queensland State Election. The heavily defeated Australian Labor Party Government of former Premier Anna Bligh attempted to be bold but was regarded by hundreds of thousands of voters as lacking in faithfulness. It was this clear perception of Labor in the eyes of voters as being out-of-touch, incompetent and unwilling to listen that cost the ALP Government in Queensland what is the worst electoral defeat in the Party’s own history. It was only the sixth time a sitting Government had been ousted since 1915, with the Parliamentary majority given to the Liberal National Party being the highest ever recorded in the State’s 152 year electoral history. 1 The following Table shows the general trend of results. Election/Votes LNP ALP Katter’s Party 2009 Election 34 Seats 51 Seats - 2012 Election 77 Seats 7 Seats 2 Seats Votes Gained 1,115,303 599,122 256,633 % Of Vote 49.85% 26.78% 11.47% % Swing Plus 8.25% Minus 15.47% Plus 11.47% The extent of the political destruction overtaking Labor can also be seen from the large number of former Ministers of the Crown who humiliatingly lost their seats. Minister Portfolio Seat Andrew Fraser Deputy Premier Mt Coot-tha Stirling Infrastructure Stafford Hinchcliffe Karen Struthers Women Algester Geoff Wilson