Panchatantra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION ’ P”(Bha.t.tikāvya) is one of the boldest “B experiments in classical literature. In the formal genre of “great poem” (mahākāvya) it incorprates two of the most powerful Sanskrit traditions, the “Ramáyana” and Pánini’s grammar, and several other minor themes. In this one rich mix of science and art, Bhatti created both a po- etic retelling of the adventures of Rama and a compendium of examples of grammar, metrics, the Prakrit language and rhetoric. As literature, his composition stands comparison with the best of Sanskrit poetry, in particular cantos , and . “Bhatti’s Poem” provides a comprehensive exem- plification of Sanskrit grammar in use and a good introduc- tion to the science (śāstra) of poetics or rhetoric (alamk. āra, lit. ornament). It also gives a taster of the Prakrit language (a major component in every Sanskrit drama) in an easily ac- cessible form. Finally it tells the compelling story of Prince Rama in simple elegant Sanskrit: this is the “Ramáyana” faithfully retold. e learned Indian curriculum in late classical times had at its heart a system of grammatical study and linguistic analysis. e core text for this study was the notoriously difficult “Eight Books” (A.s.tādhyāyī) of Pánini, the sine qua non of learning composed in the fourth century , and arguably the most remarkable and indeed foundational text in the history of linguistics. Not only is the “Eight Books” a description of a language unmatched in totality for any language until the nineteenth century, but it is also pre- sented in the most compact form possible through the use xix of an elaborate and sophisticated metalanguage, again un- known anywhere else in linguistics before modern times. -

Literatura Orientu W Piśmiennictwie Polskim XIX W

Recenzent dr hab. Kinga Paraskiewicz Projekt okładki Igor Stanisławski Na okładce wykorzystano fragment anonimowego obrazu w stylu kad żarskim „Kobieta trzymaj ąca diadem” (Iran, poł. XIX w.), ze zbiorów Państwowego Muzeum Ermita żu, nr kat. VP 1112 Ksi ąż ka finansowana w ramach programu Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego pod nazw ą „Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” w latach 2013-2017 © Copyright by individual authors, 2016 ISBN 978-83-7638-926-4 KSI ĘGARNIA AKADEMICKA ul. św. Anny 6, 31-008 Kraków tel./faks 12-431-27-43, 12-421-13-87 e-mail: [email protected] Ksi ęgarnia internetowa www.akademicka.pl Spis tre ści Słowo wst ępne . 7 Ignacy Krasicki, O rymotwórstwie i rymotwórcach. Cz ęść dziewi ąta: o rymotwórcach wschodnich (fragmenty) . 9 § I. 11 § III. Pilpaj . 14 § IV. Ferduzy . 17 Assedy . 18 Saady . 20 Suzeni . 22 Katebi . 24 Hafiz . 26 § V. O rymotwórstwie chi ńskim . 27 Tou-fu . 30 Lipe . 31 Chaoyung . 32 Kien-Long . 34 Diwani Chod ża Hafyz Szirazi, zbiór poezji Chod ży Hafyza z Szyrazu, sławnego rymotwórcy perskiego przez Józefa S ękowskiego . 37 Wilhelm Münnich, O poezji perskiej . 63 Gazele perskiego poety Hafiza (wolny przekład z perskiego) przeło żył Jan Wiernikowski . 101 Józef Szujski, Rys dziejów pi śmiennictwa świata niechrze ścija ńskiego (fragmenty) . 115 Odczyt pierwszy: Świat ras niekaukaskich z Chinami na czele . 119 Odczyt drugi: Aryjczycy. Świat Hindusów. Wedy. Ksi ęgi Manu. Budaizm . 155 Odczyt trzeci: Epopeja indyjskie: Mahabharata i Ramajana . 183 Odczyt czwarty: Kalidasa i Dszajadewa [D źajadewa] . 211 Odczyt pi ąty: Aryjczycy. Lud Zendów – Zendawesta. Firduzi. Saadi. Hafis . 233 Piotr Chmielowski, Edward Grabowski, Obraz literatury powszechnej w streszczeniach i przekładach (fragmenty) . -

Introduction

1 Introduction A jackal who had fallen into a vat of indigo dye decided to exploit his mar- velous new appearance and declared himself king of the forest. He ap- pointed the lions and other animals as his vassals, but took the precaution of having all his fellow jackals driven into exile. One day, hearing the howls of the other jackals in the distance, the indigo jackal’s eyes filled with tears and he too began to howl. The lions and the others, realizing the jackal’s true nature, sprang on him and killed him. This is one of India’s most widely known fables, and it is hard to imagine that anyone growing up in an Indian cultural milieu would not have heard it. The indigo jackal is as familiar to Indian childhood as are Little Red Rid- ing Hood or Snow White in the English-speaking world. The story has been told and retold by parents, grandparents, and teachers for centuries in all the major Indian languages, both classical and vernacular. Versions of the collec- tion in which it first appeared, the Pañcatantra, are still for sale at street stalls and on railway platforms all over India. The indigo jackal and other narratives from the collection have successfully colonized the contemporary media of television, CD, DVD, and the Internet. I will begin by sketching the history and development of the various families of Pañcatantra texts where the story of the indigo jackal first ap- peared, starting with Pu–rnabhadra’s. recension, the version on which this inquiry is based. -

Abstract 2005

Seminar on Subh¢¾hita, Pa®chatantra and Gnomic Literature in Ancient and Medieval India Saturday, 27th December 2008 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS ‘Shivshakti’, Dr. Bedekar’s Hospital, Naupada, Thane 400 602 Phone: 2542 1438, 2542 3260 Fax: 2544 2525 e-mail: [email protected] URL : http://www.orientalthane.com 1 I am extremely happy to present the book of abstracts for the seminar “Subhashita, Panchatantra and Gnomic Literature in Ancient and Medieval India”. Institute for Oriental Study, Thane has been conducting seminars since 1982. Various scholars from India and abroad have contributed to the seminars. Thus, we have a rich collection of research papers in the Institute. Indian philosophy and religion has always been topics of interest to the west since opening of Sanskrit literature to the West from late 18th century. Eminent personalities both in Europe and American continents have further contributed to this literature from the way they perceived our philosophy and religion. The topic of this seminar is important from that point of view and almost all the participants have contributed something new to the dialogue. I am extremely thankful to all of them. Dr. Vijay V. Bedekar President Institute for Oriental Study, Thane 2 About Institute Sir/Madam, I am happy to inform you that the Institute for Oriental Study, Thane, founded in 1984 has entered into the 24th year of its existence. The Institute is a voluntary organization working for the promotion of Indian culture and Sanskrit language. The Institute is registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860 (No.MAH/1124/Thane dated 31st Dec.,1983) and also under the Bombay Public Trusts Act 1950 (No.F/1034/Thane dated 14th March, 1984). -

The Semiotics of Axiological Convergences and Divergences1 Ľubomír Plesník

DOI: 10.2478/aa-2020-0004 West – East: The semiotics of axiological convergences and divergences1 Ľubomír Plesník Professor Ľubomír Plesník works as a researcher and teacher at the Institute of Literary and Artistic Communication (from 1993 to 2003 he was the director of the Institute, and at present he is the head of the Department of Semiotic Studies within the Institute). His research deals primarily with problems of literary theory, methodology and semiotics of culture. Based on the work of František Miko, he has developed concepts relating to pragmatist aesthetics, reception poetics and existential semiotics with a special focus on comparison of Western and oriental epistemes (Pragmatická estetika textu 1995, Estetika inakosti 1998, Estetika jednakosti 2001, Tezaurus estetických výrazových kvalít 2011). Abstract: This study focuses on the verbal representation of life strategies in Vetalapanchavimshati, an old Indian collection of stories, which is part of Somadeva’s Kathasaritsagara. On the basis of the aspect of gain ~ loss, two basic life strategies are identified. The first one, the lower strategy, is defined by an attempt to obtain material gain, which is attained at the cost of a spiritual loss. The second one, the higher strategy, negates the first one (spiritual gain attained at the cost of a material loss) and it is an internally diversified series of axiological models. The core of the study explains the combinatorial variants which, in their highest positions, even transcend the gain ~ loss opposition. The final part of the study demonstrates the intersections between the higher strategy and selected European cultural initiatives (gnosis). 1. Problem definition, area of concern and material field Our goal is to reflect on the differences and intersections in the iconization of gains and losses in life between the Western and Eastern civilizations and cultural spheres. -

Istanbul 2016 T.C. Fatih Sultan Mehmet Vakif Üniversitesi

T.C. FATİH SULTAN MEHMET VAKIF ÜNİVERSİTESİ MEDENİYETLER İTTİFAKI ENSTİTÜSÜ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ BİLİMSEL BİR SÖYLEM FORMU OLARAK TEMSİL: MANDEVİLLE’İN ARILAR MASALI ÜZERİNE BİR İNCELEME FİRDEVS BULUT 130401003 TEZ DANIŞMANI: PROF. DR. RECEP ŞENTÜRK PROF. DR. TAHSİN GÖRGÜN ISTANBUL 2016 T.C. FATİH SULTAN MEHMET VAKIF ÜNİVERSİTESİ MEDENİYETLER İTTİFAKI ENSTİTÜSÜ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ BİLİMSEL BİR SÖYLEM FORMU OLARAK TEMSİL: MANDEVİLLE’İN ARILAR MASALI ÜZERİNE BİR İNCELEME FİRDEVS BULUT 130401003 Enstitü Anabilim Dalı: Medeniyet Araştırmaları Enstitü Bilim Dalı: Medeniyet Araştırmaları Bu tez 23/06/2016 tarihinde aşağıdaki jüri tarafından oy birliğiyle kabul edilmiştir. BEYAN Bu tezin yazımında bilimsel ahlâk kurallarının gözetildiğini, başkalarının eserlerinden yararlanırken bilimsel normlara uygun olarak kaynak gösteriminin yapıldığını, kullanılan veriler üzerinde herhangi bir değişiklik yapılmadığını, tezin herhangi bir kısmının bu üniversite veya başka bir üniversitedeki başka bir tez çalışmasına ait olarak sunulmadığını beyan ederim. FİRDEVS BULUT ÖZET Bu tezde, Bernard de Mandeville’in 1714 yılında kaleme aldığı ve klasik temsili anlatım türünün bir örneği olan Arılar Masalı (The Fable of the Bees) eseri incelenecek, metinde öne çıkan kavramlar ve metnin yazıldığı dönemin özellikleri, temsili anlatım ile bilgi üretimi arasındaki ilişkiyi ortaya koyması açısından ele alınacaktır. Ortaya koyduğu toplum teorisi ve erken modern Batı toplumu örnekliği ile yazıldığı dönemin ender eserlerinden biri olan Arılar Masalı, bu çalışmada öncelikle döneminin düşünsel birikiminin bir parçası olarak değerlendirilecektir. Daha sonra metnin şu ana kadarki iktisadi ve ahlaki açıklama ve yorumlarının ötesine geçilmeye çalışılarak, edebi bir metin olarak ele alınacaktır. Fabl türü ve temsil getirme metodu ile siyasi ve ahlaki bir toplum teorisi kuran eserin, bir edebiyat ürünü olarak döneminin neresinde bulunduğu açıklanacaktır. -

Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets

Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2016 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2018 © Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets submitted by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies Examining Committee: Adheesh Sathaye, Asian Studies Supervisor Thomas Hunter, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Anne Murphy, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Additional Examiner ii Abstract In this thesis, I discuss classical Sanskrit women poets and propose an alternative reading of two specific women’s works as a way to complicate current readings of Classical Sanskrit women’s poetry. I begin by situating my work in current scholarship on Classical Sanskrit women poets which discusses women’s works collectively and sees women’s work as writing with alternative literary aesthetics. Through a close reading of two women poets (c. 400 CE-900 CE) who are often linked, I will show how these women were both writing for a courtly, educated audience and argue that they have different authorial voices. In my analysis, I pay close attention to subjectivity and style, employing the frameworks of Sanskrit aesthetic theory and Classical Sanskrit literary conventions in my close readings. -

Mitrasamprapthi Preliminary

i ^GÈ8ZHB ^GD^09 QP9·¦R ^B¦J¿ºP^»f ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ ¥¶D˶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ )¶X¶À» ˶Ç˶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç· 2·Ç¦~º»À¥»¶Td¶Ç¶}˶·ª·¶U¶ ¶Ç·¶2¶¶» X· #˶ X· 2À$d 2¶»¤¶»»¶¤¶¢£ ¶··Ç9¶ ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· » ÀÇQ¡d2·¡ÀºI»$¤¶¶^ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» ii Blank iii ¤¶»»¶»Y ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» 2ÀºÇ¶ ¥§¶¦¥· »¶ ¶Ç¶}˶ #¶»¶ ¤¶»ÇX¶´»» )¶X¶Àº À¥»¶Td 2·Ç ¶¶¥ ˶¶9¶~» ¶Ç¶}˶ ¥·Æ9¶´9À¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ¥¶D˶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶·9¶¤¶¶»¶U¶¤¶·: 9¶¶Y®À ·¶~º» ¶Ç¶}~» ¶J·P¶ °·9¶½ ¤¶¸¶¥º» ¤¶¿Â 9¶³¶¶C¶»2À4¶Ç¶}˶·ª·¶»¶#˶¤¶§¶2¶¤·:À ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ ¥¶D˶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç·» & ¶U¶¤¶¶» #·¶2¶ °·9¶½ ¥·Æ¤¶ÄǶ2À4 #¶»2¶½ ¤·9¶»¤¶ º~»¢£ ¶2· 2À4®¶y¶Y®2À½QTX·#˶°·9¶½X·2À$d2¶»¤¶»»¶¤¶¢£ #¤¶9À¶¶¤·¶9¶³¶» ¶Ç¶}˶ #·¶2¶¶» °·9¶½ ¥·Æ9¶³¶» & 2¶Ä~»¶» ¶¶»¶½º9¶¶XÀ»»¤¶ÀǶ»$¨¶»ËÀºÀ À¾vJ·ÀRd '¶2¶» ¶~9¶³¶» ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· » ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» iv Blank v ¶Ç·¶2¶¶¶»Y ¶Ç¶}˶ ·±Ë¶ ¶2·¶9¶³¶¢£ ,Ç·¶ 2¶··±Ë¶¤¶¼ ¥§¶¦¶®¶y¤·¶»¶»%Ç˶°¶·±Ë¶¶#¶»¶¤¶¼%Ç9¶½#˶Ç˶ ¶¶»Ë¶¤·:À & 2¶··±Ë¶ 9¶Ç¶9¶³¶¢£ ¶¤¶»»5¤·¶ ,Ƕ» 2¶Ä~ ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ¥¶D˶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶vÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· »¶ ¶Ç¶}˶ #¶»¶ ¤¶»ÇX¶´»» Àº §ÀÁ2¶¬`2¶ ¤¶ª¶ÆǶ J·9À z¶»¤¶ÇËÀ ¦~º» À¥»¶Td 2·Ç ˶¶9¶~9À ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç·» ,Ƕ» ·9¶¤¶¶» ¶U¶¤¶·: 9¶¶Y®Ë¶» %¶¶ ¶Ç·¶·2·»Æ¤¶¶»¶¤¶»9À¤¶±®Ë¶»¤¶»ÇX¶´»¶½C¶À»ÇËÀ #·¶2¶¶» °·9¶½ ¥·Æ9¶´9À #¶»2¶½ ¤·9¶»¤¶ º~»¢£ & ¶U¶¤¶¶»®¶y¶Y¶¡·:À ¤¶»½ ¶Ç¶}˶ ¶U¶·9¶¤¶¶» 2¶Äª¶|·¶ #2·X¶¥» ¤·¶1·® ¶2¶Q¶Y®¶»¤¶X·¶»·2¶¶¤¶¸ ¥º»%¤¶¶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¤¶¿d )Çz2¶Ä~»Ç¶®¦º2¶¶¡·:À &¶U¶2À4JÀ¶£¨Ç9d°ÂdÀ°¶¢X·¶¥ºd2¶»¤¶¸d ¶M¸ ¤¶»Ë¶» X· #ÇI· %¤¶¶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¤¶¿d ¶¼¶2¶¶ $Ç9¶£ #¶»¤·¶¤¶¶» »·¤¶Ë·: ®¦º2¶¶¡·:À & ¶U¶¶¼¶2¶¶ ¶C¶À»¢£ #Àº2¶ 2¶Ä~9¶³¶ ¶°·»¤¶¶» ¶XÀ»¡·:À & )¡·£ 9¶Ç¶2¶Ë¶ÄÆ9¶´9¶½·¤¶¼$·¸:¶»ËÀº¤À & ¶U¶¶ 2¶¶X¶ -

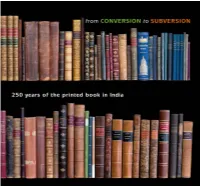

From Conversion to Subversion a Selection.Pdf

2014 FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India 2014 From Conversion to Subversion: 250 years of the printed book in India. A catalogue by Graham Shaw and John Randall ©Graham Shaw and John Randall Produced and published in 2014 by John Randall (Books of Asia) G26, Atlas Business Park, Rye, East Sussex TN31 7TE, UK. Email: [email protected] All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission in writing of the publisher and copyright holder. Designed by [email protected], Devon Printed and bound by Healeys Print Group, Suffolk FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India his catalogue features 125 works spanning While printing in southern India in the 18th the history of print in India and exemplify- century was almost exclusively Christian and Ting the vast range of published material produced evangelical, the first book to be printed in over 250 years. northern India was Halhed’s A Grammar of the The western technology of printing with Bengal Language (3), a product of the East India movable metal types was introduced into India Company’s Press at Hooghly in 1778. Thus by the Portuguese as early as 1556 and used inter- began a fertile period for publishing, fostered mittently until the late 17th century. The initial by Governor-General Warren Hastings and led output was meagre, the subject matter over- by Sir William Jones and his generation of great whelmingly religious, and distribution confined orientalists, who produced a number of superb to Portuguese enclaves. -

Report of the Jewish Publication Society of America

REPORT OF THE TWENTY-SIXTH YEAR OF THE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OF AMERICA 1913-1914 JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY 421 THE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OP AMERICA OFFICERS PRESIDENT SIMON MILLER, Philadelphia FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT DR. HENRY M. LEIPZIGER, New York SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT HORACE STERN, Philadelphia TREASURER HENRY FERNBERGER, Philadelphia SECRETARY BENJAMIN ALEXANDER, Philadelphia ASSISTANT SECRETARY I. GEORGE DOBSEVAGE, Philadelphia SECRETARY TO THE PUBLICATION COMMITTEE HENRIETTA SZOLD, New York TRUSTEES DR. CYRUS ADLER 3 Philadelphia HART BLUMENTHAL 2 Philadelphia CHARLES EISENMAN 2 Cleveland HENRY FERNBERGER * Philadelphia 2 DANIEL GUGGENHEIM New York 1 JOSEPH HAGEDORN Philadelphia 2 EPHRAIM LEDEEER Philadelphia DR. HENRY M. LEIPZIGER S New York SIMON MILLER2 Philadelphia ! MOBRIS NEWBUKGEE New York JULIUS ROSENWALD * Chicago SIGMUND B. SONNEBORN J Baltimore HORACE STERN * Philadelphia a SAMUEL STRAUSS New York 1 HON. SELIGMAN J. STRAUSS Wilkes-Barre, Pa. 1 CYRUS L. SULZBERGER New York 1 Term expires in 1915. 2 Term expires in 1916. 3 Term expires in 1917. 3 422 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK HON. MAYEB SULZBERGER 8 Philadelphia A. LEO WEIL3 Pittsburgh 2 HARBIS WEINSTOCK Sacramento EDWIN WOLF' Philadelphia HONORARY VICE-PRESIDENTS 1 ISAAC W. BERNHEIM Louisville REV. DR. HENRY COHEN 3 Galveston 8 Louis K. GTJTMAN Baltimore REV. DR. MAX HELLER * New Orleans 2 Miss ELLA JACOBS Philadelphia S. W. JACOBS • Montreal HON. JULIAN W. MACK * Washington REV. DR. MARTIN A. MEYER 2 San Francisco HON. SIMON W. ROSENDALE = Albany, N. Y. 8 MURRAY SEASONGOOD Cincinnati HON. M. C. SLOSS * San Francisco REV. DR. JOSEPH STOLZ * Chicago HON. SIMON WOLF * Washington, D. C. PUBLICATION COMMITTEE HON. MAYER SULZBERGER, Chairman Philadelphia DB. -

Article (176.8Kb)

garcin de tassy Origin and Diffusion of Hindustani [translator’s note: Presented here is the translation of a memorandum entitled ìOrigine et Diffusion de líHindoustani Appelé Language Générale ou Nationale de líIndeî (Origin and Diffusion of Hindustani, Called the Common or National Language of India) by Garcin de Tassy (1871) published in the transactions of the Royal Academy of Science, Arts, and Belles-Lettres of Caen, France. Written in the last decade of his life, this brief memorandum contains some of his observations and conclusions based on over half a century of involvement with Indian languagesóespecially Urdu, which was gener- ally called Hindustani during his time. Most of his peer academy members, to whom this communication was directed, probably did not know much about Urdu. Consequently, he includes some explanations and background information that would seem too elementary nowadays. Nevertheless, some of his remarks still seem fresh and surprising. Even his digressionary remarks, which are dispersed throughout the note and which often seem factitious, contain much information about the historical and cultural factors influencing the development of Urdu. The note also reveals de Tassyís passionate at- tachment to Urdu and his angst over the Urdu-Hindi controversy which, he thought, was going to lead to disastrous religious and political strife in India.] We can only make conjectures about the exact dates of Indiaís invasion by the Aryans and the diffusion of their language; the language was called Sanskrit (well-formed), in contrast to the language of the natives and its various dialects that were together given the name Prakrit (ill-formed) by the scornful victors. -

Buddhacarita

CLAY SANSKRIT LIBRARY Life of the Buddka by AsHvaghosHa NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS & JJC EOUNDATION THE CLAY SANSKRIT LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JOHN & JENNIFER CLAY GENERAL EDITORS RICHARD GOMBRICH SHELDON POLLOCK EDITED BY ISABELLE ONIANS SOMADEVA VASUDEVA WWW.CLAYSANSBCRITLIBRARY.COM WWW.NYUPRESS.ORG Copyright © 2008 by the CSL. All rights reserved. First Edition 2008. The Clay Sanskrit Library is co-published by New York University Press and the JJC Foundation. Further information about this volume and the rest of the Clay Sanskrit Library is available at the end of this book and on the following websites: www.ciaysanskridibrary.com www.nyupress.org ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-6216-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-6216-6 (cloth : alk. paper) Artwork by Robert Beer. Typeset in Adobe Garamond at 10.2$ : 12.3+pt. XML-development by Stuart Brown. Editorial input from Linda Covill, Tomoyuki Kono, Eszter Somogyi & Péter Szântà. Printed in Great Britain by S t Edmundsbury Press Ltd, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on acidffee paper. Bound by Hunter & Foulis, Edinburgh, Scotland. LIFE OF THE BUDDHA BY ASVAGHOSA TRANSLATED BY PATRICK OLIVELLE NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS JJC FOUNDATION 2008 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Asvaghosa [Buddhacarita. English & Sanskrit] Life of the Buddha / by Asvaghosa ; translated by Patrick Olivelle.— ist ed. p. cm. - (The Clay Sanskrit library) Poem. In English and Sanskrit (romanized) on facing pages. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-6216-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-6216-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Gautama Buddha-Poetry. I. Olivelle, Patrick. II.