The River Teno System (70ºN, 28ºE) Has a Catchment Area of 16 386 Km² One-Third of It Being Located in Finland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migratory Fish Stock Management in Trans-Boundary Rivers

Title Migratory fish stock management in trans-boundary rivers Author(s) Erkinaro, Jaakko フィンランド-日本 共同シンポジウムシリーズ : 北方圏の環境研究に関するシンポジウム2012(Joint Finnish- Citation Japanese Symposium Series Northern Environmental Research Symposium 2012). 2012年9月10日-14日. オウル大学 、オウランカ研究所, フィンランド. Issue Date 2012-09-10 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/51370 Type conference presentation File Information 07_JaakkoErkinaro.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Migratory fish stock management in trans-boundary rivers Jaakko Erkinaro Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Oulu Barents Sea Atlantic ocean White Sea Baltic Sea Finland shares border river systems with Russia, Norway and Sweden that discharge to the Baltic Sea or into the Atlantic Ocean via White Sea or Barents Sea Major trans-boundary rivers between northern Finland and neighbouring countries Fin-Swe: River Tornionjoki/ Torneälven Fin-Nor: River Teno / Tana Fin-Rus: River Tuuloma /Tuloma International salmon stock management • Management of fisheries in international waters: International fisheries commissions, European Union • Bilateral management of trans-boundary rivers: Bilateral agreements between governments • Regional bilateral management Bilateral agreements between regional authorities Advice from corresponding scientific bodies International and bilateral advisory groups International Council for the Exploration of the Sea - Advisory committee for fisheries management - Working groups: WG for Baltic salmon and sea trout -

Troms Og Finnmark

Kommunestyre- og fylkestingsvalget 2019 Valglister med kandidater Fylkestingsvalget 2019 i Troms og Finnmark Valglistens navn: Partiet De Kristne Status: Godkjent av valgstyret Kandidatnr. Navn Fødselsår Bosted Stilling 1 Svein Svendsen 1993 Alta 2 Karl Tobias Hansen 1992 Tromsø 3 Torleif Selseng 1956 Balsfjord 4 Dag Erik Larssen 1953 Skånland 5 Papy Zefaniya 1986 Sør-Varanger 6 Aud Oddrun Grønning 1940 Tromsø 7 Annbjørg Watnedal 1939 Tromsø 8 Arlene Marie Hansen 1949 Balsfjord 04.06.2019 12:53:00 Lister og kandidater Side 1 Kommunestyre- og fylkestingsvalget 2019 Valglister med kandidater Fylkestingsvalget 2019 i Troms og Finnmark Valglistens navn: Høyre Status: Godkjent av valgstyret Kandidatnr. Navn Fødselsår Bosted Stilling 1 Christine Bertheussen Killie 1979 Tjeldsund 2 Jo Inge Hesjevik 1969 Porsanger 3 Benjamin Nordberg Furuly 1996 Bardu 4 Tove Alstadsæter 1967 Sør-Varanger 5 Line Fusdahl 1957 Tromsø 6 Geir-Inge Sivertsen 1965 Senja 7 Kristen Albert Ellingsen 1961 Alta 8 Cecilie Mathisen 1994 Tromsø 9 Lise Svenning 1963 Vadsø 10 Håkon Rønning Vahl 1972 Harstad 11 Steinar Halvorsen 1970 Loppa 12 Tor Arne Johansen Morskogen 1979 Tromsø 13 Gro Marie Johannessen Nilssen 1963 Hasvik 14 Vetle Langedahl 1996 Tromsø 15 Erling Espeland 1976 Alta 16 Kjersti Karijord Smørvik 1966 Harstad 17 Sharon Fjellvang 1999 Nordkapp 18 Nils Ante Oskal Eira 1975 Lavangen 19 Johnny Aikio 1967 Vadsø 20 Remi Iversen 1985 Tromsø 21 Lisbeth Eriksen 1959 Balsfjord 22 Jan Ivvar Juuso Smuk 1987 Nesseby 23 Terje Olsen 1951 Nordreisa 24 Geir-Johnny Varvik 1958 Storfjord 25 Ellen Kristina Saba 1975 Tana 26 Tonje Nilsen 1998 Storfjord 27 Sebastian Hansen Henriksen 1997 Tromsø 28 Ståle Sæther 1973 Loppa 29 Beate Seljenes 1978 Senja 30 Joakim Breivik 1992 Tromsø 31 Jonas Sørum Nymo 1989 Porsanger 32 Ole Even Andreassen 1997 Harstad 04.06.2019 12:53:00 Lister og kandidater Side 2 Kommunestyre- og fylkestingsvalget 2019 Valglister med kandidater Fylkestingsvalget 2019 i Troms og Finnmark Valglistens navn: Høyre Status: Godkjent av valgstyret Kandidatnr. -

Development in the Pink Salmon Catches in the Transboundary Rivers

Development in the Pink salmon catches in the transboundary rivers of Tana and Neiden-in Norway and Finland Niemelä, Hassinen, Johansen, Kuusela, Länsman, Haantie, Kylmäaho • Who can identify pink and Atlantic salmon • Feelings against pink salmon • First catches in the history • Distribution in the River Tana watershed • Total catches in the rivers Tana and Neiden • Timing of the catches • Ecology ©© NaturalNatural ResourcesResources InstituteInstitute FinlandFinland To recognize silvery pink salmon might be difficult for tourist fishermen or even for some local fishermen early in the summer 2 6.2.2018 © Natural Resources Institute Finland In the second half of July and especially in August fishermen have no problem to distinguish Atlantic salmon and Pacific salmon in the catches 3 6.2.2018 © Natural Resources Institute Finland Fishermen do not like this new fish species in their catches especially in the end of July and August. Why? 4 6.2.2018 © Natural Resources Institute Finland Why not pink salmon in the catches? • Local fishermen are not get used to catch other species than salmon and seatrout • Tourist fishermen have payed a lot of money to catch silvery Atlantic salmon • Local fishermen catching Atlantic salmon with gillnets and weirs have an opinion that pink salmon in their fishing gears are scaring the real target, Atlantic salmon, away. Does this scaring help Atlantic salmon to avoid to be caught with traditional fishing methods? • In rod fishing from shore and boat pink salmon is disturbing the real Atlantic salmon fishery. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic. -

DRAINAGE BASINS of the WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA and KARA SEA Chapter 1

38 DRAINAGE BASINS OF THE WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA Chapter 1 WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA 39 41 OULANKA RIVER BASIN 42 TULOMA RIVER BASIN 44 JAKOBSELV RIVER BASIN 44 PAATSJOKI RIVER BASIN 45 LAKE INARI 47 NÄATAMÖ RIVER BASIN 47 TENO RIVER BASIN 49 YENISEY RIVER BASIN 51 OB RIVER BASIN Chapter 1 40 WHITE SEA, BARENT SEA AND KARA SEA This chapter deals with major transboundary rivers discharging into the White Sea, the Barents Sea and the Kara Sea and their major transboundary tributaries. It also includes lakes located within the basins of these seas. TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS IN THE BASINS OF THE BARENTS SEA, THE WHITE SEA AND THE KARA SEA Basin/sub-basin(s) Total area (km2) Recipient Riparian countries Lakes in the basin Oulanka …1 White Sea FI, RU … Kola Fjord > Tuloma 21,140 FI, RU … Barents Sea Jacobselv 400 Barents Sea NO, RU … Paatsjoki 18,403 Barents Sea FI, NO, RU Lake Inari Näätämö 2,962 Barents Sea FI, NO, RU … Teno 16,386 Barents Sea FI, NO … Yenisey 2,580,000 Kara Sea MN, RU … Lake Baikal > - Selenga 447,000 Angara > Yenisey > MN, RU Kara Sea Ob 2,972,493 Kara Sea CN, KZ, MN, RU - Irtysh 1,643,000 Ob CN, KZ, MN, RU - Tobol 426,000 Irtysh KZ, RU - Ishim 176,000 Irtysh KZ, RU 1 5,566 km2 to Lake Paanajärvi and 18,800 km2 to the White Sea. Chapter 1 WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA 41 OULANKA RIVER BASIN1 Finland (upstream country) and the Russian Federation (downstream country) share the basin of the Oulanka River. -

Salmon Sans Borders

Scandinavia TRADITIONAL FISHING Salmon Sans Borders Fishing for salmon along the Deatnu or Tana river has long been fundamental to the culture of the indigenous Sámi people along the Finland-Norway border ishing for salmon (Salmo Danish-Norwegian jurisdiction. This salar) along the over 200-km had consequences for the territorial Fwatercourse on the border of division of the Tana river valley too. Finland and Norway, called Deatnu From then until the present border (in the Sámi language) or Tana (in was drawn in 1751, Denmark-Norway Norwegian), has been going on for at had exclusive jurisdiction over the least 7,000 to 8,000 years, or for as long lowest 30-40 km of the river. Juridical as human existence after the last Ice and clerical jurisdiction over the rest Age. The Tana river valley is situated in of the valley belonged to the Swedish an area in which the Sámi are the oldest realm. But the Sámi still had to pay known ethnic group. Sámi culture, as taxes to Denmark-Norway. it exists in northern Scandinavia and Until 1809, Finland belonged to 4 the northwestern parts of Russia, is at Sweden. Then it became a Grand Duchy least 2,000 to 3,000 years old. Salmon under the Russian Tsar. The border fishing remains a fundamental part along the Tana watercourse became the of Sámi culture on both sides of the border between Finland and Norway. Finland-Norway border. Neither this change, nor the separation The first written sources from this of Norway from Denmark in 1814 river district date to the end of the 16th and its union with Sweden, had any century. -

General Fishing Rules for Visitors Anglers in Tana River System

Tanavassdragets fiskeforvaltning- Deanučázádaga guolástanhálddahus-Tana River Fish Management General fishing rules for visitors anglers in Tana River System 1. Fishing areas Persons living permanently in Norway are permitted to fish on the border area, in the Norwegian tributaries and in the lower, Norwegian part of Tana River. Persons not living permanently in Norway, are not allowed to fish in the Norwegian tributaries of Tana river, except in the lower part of Tana main stem and the lower part of Kárášjohka downstream the joint of Iešjohka and Kárášjohka. The fishing rules for the Tana River applies for the salmon-area. In some of the tributaries that area is marked with signs. Above the salmon-area, the ordinary rules and fishing license for freshwater fisheries in Finnmark, apply. 2. Fishing time Fishing is prohibited from Sunday 18:00 hrs to Monday 180:0 hrs (Norwegian time). There is one exception: the area from Tana River mouth up to Langnes. 3. Minimum size Catching salmon, trout or char smaller than 25 cm is prohibited. Kelts must be released to the river. 4. Forbidden methods and areas Prohibited baits: prawns, shrimps, fish and earthworms. Using the fishing gear to hook the fish is not allowed. Rod fishing is prohibited within the fish fence guide-nets, within 50 m downstream of the fence, and 10 m to either side. Fishing is also prohibited within a 10 m distance from gill nets. In the main river it is prohibited to fish with rod from shore and boat within a 50 m distance downstream and upstream of the river mouths of salmon tributaries. -

Status of the River Tana Salmon Populations

STATUS OF THE RIVER TANA SALMON POPULATIONS REPORT 1-2012 OF THE WORKING GROUP ON SALMON MONITORING AND RESEARCH IN THE TANA RIVER SYSTEM Contents 1 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2 The group mandate and presentation of members ..................................................................... 10 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 11 4 The River Tana, the Tana salmon, salmon fisheries and management ........................................ 12 4.1 The Tana and its salmon ....................................................................................................... 12 4.2 Tana salmon fisheries ........................................................................................................... 17 4.3 Management of the Tana salmon fishing ............................................................................. 28 5 Local/traditional knowledge and local contact ............................................................................. 29 5.1 How the Group will approach these issues........................................................................... 29 5.2 Current locally raised issues .................................................................................................. 31 5.2.1 Predation ...................................................................................................................... -

Riessler/Wilbur: Documenting the Endangered Kola Saami Languages

BERLINER BEITRÄGE ZUR SKANDINAVISTIK Titel/ Språk og språkforhold i Sápmi title: Autor(in)/ Michael Riessler/Joshua Wilbur author: Kapitel/ »Documenting the endangered Kola Saami languages« chapter: In: Bull, Tove/Kusmenko, Jurij/Rießler, Michael (Hg.): Språk og språkforhold i Sápmi. Berlin: Nordeuropa-Institut, 2007 ISBN: 973-3-932406-26-3 Reihe/ Berliner Beiträge zur Skandinavistik, Bd. 11 series: ISSN: 0933-4009 Seiten/ 39–82 pages: Diesen Band gibt es weiterhin zu kaufen. This book can still be purchased. © Copyright: Nordeuropa-Institut Berlin und Autoren. © Copyright: Department for Northern European Studies Berlin and authors. M R J W Documenting the endangered Kola Saami languages . Introduction The present paper addresses some practical and a few theoretical issues connected with the linguistic field research being undertaken as part of the Kola Saami Documentation Project (KSDP). The aims of the paper are as follows: a) to provide general informa- tion about the Kola Saami languages und the current state of their doc- umentation; b) to provide general information about KSDP, expected project results and the project work flow; c) to present certain soft- ware tools used in our documentation work (Transcriber, Toolbox, Elan) and to discuss other relevant methodological and technical issues; d) to present a preliminary phoneme analysis of Kildin and other Kola Saami languages which serves as a basis for the transcription convention used for the annotation of recorded texts. .. The Kola Saami languages The Kola Saami Documentation Project aims at documenting the four Saami languages spoken in Russia: Skolt, Akkala, Kildin, and Ter. Ge- nealogically, these four languages belong to two subgroups of the East Saami branch: Akkala and Skolt belong to the Mainland group (together with Inari, which is spoken in Finland), whereas Kildin and Ter form the Peninsula group of East Saami. -

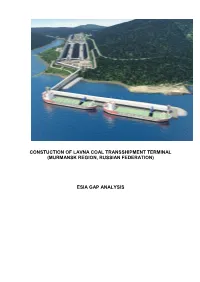

Lavna Coal Transshipment Terminal Gap-Analysis

CONSTUCTION OF LAVNA COAL TRANSSHIPMENT TERMINAL (MURMANSK REGION, RUSSIAN FEDERATION) ESIA GAP ANALYSIS CONSTUCTION OF LAVNA COAL TRANSSHIPMENT TERMINAL (MURMANSK REGION, RUSSIAN FEDERATION) ESIA GAP ANALYSIS Prepared by: Ecoline Environmental Assessment Centre (Moscow, Russia) Director: Dr. Marina V. Khotuleva ___________________________ Tel./Fax: +7 495 951 65 85 Address: 21, Build.8, Bolshaya Tatarskaya, 115184, Moscow, Russian Federation Mobile: +7 903 5792099 e-mail: [email protected] Prepared for: Black Sea Trade and Development Bank (BSTDB) © Ecoline EA Centre NPP, 2018 CONSTUCTION OF LAVNA COAL TRANSSHIPMENT TERMINAL (MURMANSK REGION, RUSSIAN FEDERATION). ESIA GAP ANALYSIS REPORT DETAILS OF DOCUMENT PREPARATION AND ISSUE Version Prepared by Reviewed Authorised for Issue Date Description by issue 0 Dr. Marina Dr. Olga Dr. Marina 23/11/2018 Version for Khotuleva Demidova Khotuleva BSTDB’s Dr. Tatiana internal review Laperdina Anna Kuznetsova 3 CONSTUCTION OF LAVNA COAL TRANSSHIPMENT TERMINAL (MURMANSK REGION, RUSSIAN FEDERATION). ESIA GAP ANALYSIS REPORT LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS BAT Best Available Techniques BREF BAT Reference Document BSTDB Black Sea Trade and Development Bank CLS Core Labour Standards CTS Conveyor transport system CTT Coal Transshipment Terminal E&S Environmental and Social EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EEC European Economic Council EES Environmental and Engineering Studies EHS Environmental, Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIB European Investment Bank EPC Engineering, -

The European Union and the Barents Region

The European Union and the Barents Region lt) (W) ........... v - . ww f () I '"../'::!")/-) -) U 'Ll7 n../c- V t./i ::I -, t../d' ~, <-?•'' )/ '1 What is the European Union? Growing from six Members States in 1952 to 15 by The European Commission, headed by 20 Commis 1995, the European Union today embraces more than sioners, is the motor of European integration. It 370 million people, from the Arctic Circle to Portugal , suggests the policies to be developed and also from Ireland to Crete. Though rich in diversity, the implements them. The Commission is the executive Member States share certain common values. By instrument of the European Union. It sees to it that the entering into partnership together, their aim is to Member States adequately apply the decisions taken promote democracy, peace, prosperity and a fairer and situates itself in the middle of the decision-making distribution of wealth. process of the European Union . The Members of the Commission operate with a clear distribution of tasks. After establishing a true frontier-free Europe by For example, Mr Hans van den Broek has overall eliminating the remaining barriers to trade among responsibility for external relations with European themselves, the Member States of t he European Countries and the New Independent States. Union have resolved to respond to the major economic and social challenges of the day - to The European Parliament represents the people of establish a common currency, boost employment and Europe. It examines law proposals and has the final strengthen Europe's role in world affairs. In so doing, word on the budget. -

FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL and BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O

JOURNAL OF INNISH TUDIES F S Volume 19 Number 1 June 2016 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-937875-94-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University; hilary.virtanen@finlandia. edu Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Titus Hjelm, Reader, University College London Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of Finnish Literature, University of Helsinki Juha