Hawaiian Historical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaii Been Researched for You Rect Violation of Copyright Already and Collected Into Laws

COPYRIGHT 2003/2ND EDITON 2012 H A W A I I I N C Historically Speaking Patch Program ABOUT THIS ‘HISTORICALLY SPEAKING’ MANUAL PATCHWORK DESIGNS, This manual was created Included are maps, crafts, please feel free to contact TABLE OF CONTENTS to assist you or your group games, stories, recipes, Patchwork Designs, Inc. us- in completing the ‘The Ha- coloring sheets, songs, ing any of the methods listed Requirements and 2-6 waii Patch Program.’ language sheets, and other below. Answers educational information. Manuals are books written These materials can be Festivals and Holidays 7-10 to specifically meet each reproduced and distributed 11-16 requirement in a country’s Games to the individuals complet- patch program and help ing the program. Crafts 17-23 individuals earn the associ- Recipes 24-27 ated patch. Any other use of these pro- grams and the materials Create a Book about 28-43 All of the information has contained in them is in di- Hawaii been researched for you rect violation of copyright already and collected into laws. Resources 44 one place. Order Form and Ship- 45-46 If you have any questions, ping Chart Written By: Cheryle Oandasan Copyright 2003/2012 ORDERING AND CONTACT INFORMATION SPECIAL POINTS OF INTEREST: After completing the ‘The Patchwork Designs, Inc. Using these same card types, • Celebrate Festivals Hawaii Patch Program’, 8421 Churchside Drive you may also fax your order to Gainesville, VA 20155 (703) 743-9942. • Color maps and play you may order the patch games through Patchwork De- Online Store signs, Incorporated. You • Create an African Credit Card Customers may also order beaded necklace. -

The Dread Taboo, Human Sacrifice, and Pearl Harbor

The Dread Taboo, Human Sacrifice, and Pearl Harbor RDKHennan The word taboo, or tabu, is well known to everyone, but it is especially interesting that it is one of but two or possibly three words from the Polynesian language to have been adopted by the English-speaking world. While the original meaning of the taboo was "Sacred" or "Set apart," usage has given it a decidedly secular meaning, and it has become a part of everyday speech all over the world. In the Hawaiian lan guage the word is "kapu," and in Honolulu we often see a sign on a newly planted lawn or in a park that reads, not, "Keep off the Grass," but, "Kapu." And to understand the history and character of the Hawaiian people, and be able to interpret many things in our modern life in these islands, one must have some knowledge of the story of the taboo in Hawaii. ANTOINETTE WITHINGTON, "The Dread Taboo," in Hawaiian Tapestry Captain Cook's arrival in the Hawaiian Islands signaled more than just the arrival of western geographical and scientific order; it was the arrival of British social and political order, of British law and order as well. From Cook onward, westerners coming to the islands used their own social civil codes as a basis to judge, interpret, describe, and almost uniformly condemn Hawaiian social and civil codes. With this condemnation, west erners justified the imposition of their own order on the Hawaiians, lead ing to a justification of colonialism and the loss of land and power for the indigenous peoples. -

Visibility Analysis of Oahu Heiau

Visibility Analysis of Oahu Heiau A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN GEOGRAPHY May 2012 By Kepa Lyman Thesis Committee: Matthew McGranaghan, Chair Hong Jiang William Chapman Keywords: heiau, intervisibility, viewshed analysis Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................... IV INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER OUTLINE ..................................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER I. HAWAIIAN HEIAU ............................................................................................................ 8 HEIAU AS SYMBOL ..................................................................................................................................... 8 HEIAU AS FORTRESS ................................................................................................................................. 12 TYPES ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Ad E& MAY 2 6 1967

FEBRUARY, 1966 254 &Ad e& MAY 2 6 1967 Amstrong, Richard,presents census report 145; Minister of Public Abbott, Dr. Agatin 173 Instruction 22k; 227, 233, 235, 236, Abortion 205 23 7 About A Remarkable Stranger, Story 7 Arnlstrong, Mrs. Richard 227 Adms, Capt . Alexander, loyal supporter Armstrong, Sam, son of Richard 224 of Kamehameha I 95; 96, 136 Ashford, Volney ,threatens Kalakaua 44 Adans, E.P., auctioneer 84 Ashford and Ashford 26 Adams, Romanzo, 59, 62, 110, 111, ll3, Asiatic cholera 113 Ilk, 144, 146, 148, 149, 204, 26 ---Askold, Russian corvette 105, 109 Adams Gardens 95 Astor, John Jacob 194, 195 Adams Lane 95 Astoria, fur trading post 195, 196 Adobe, use of 130 Atherton, F.C, 142 ---mc-Advertiser 84, 85 Attorney General file 38 Agriculture, Dept. of 61 Auction of Court House on Queen Street kguiar, Ernest Fa 156 85 Aiu, Maiki 173 Auhea, Chiefess-Premier 132, 133 illmeda, Mrs. Frank 169, 172 Auld, Andrew 223 Alapai-nui, Chief of Hawaii 126 Austin, James We 29 klapai Street 233 Automobile, first in islands 47 Alapa Regiment 171 ---Albert, barkentine 211 kle,xander, Xary 7 Alexander, W.D., disputes Adams 1 claim Bailey, Edward 169; oil paintings by 2s originator of flag 96 170: 171 Alexander, Rev. W.P., estimates birth mile: House, Wailuku 169, 170, 171 and death rates 110; 203 Bailey paintings 170, 171 Alexander Liholiho SEE: Kamehameha IV Baker, Ray Jerome ,photographer 80, 87, 7 rn Aliiolani Hale 1, 41 opens 84 1 (J- Allen, E.H., U.S. Consul 223, 228 Baker, T.J. -

Pacific Islands Program

/ '", ... it PACIFIC ISLANDS PROGRAM ! University of Hawaii j Miscellaneous Work Papers 1974:1 . BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE MATERIALS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII, MANOA CAMPUS Second Printing, 1979 Photocopy, Summer 1986 ,i ~ Foreword Each year the Pacific Islands Program plans to duplicate inexpensively a few work papers whose contents appear to justify a wider distribution than that of classroom contact or intra-University circulation. For the most part, they will consist of student papers submitted in academic courses and which, in their respective ways, represent a contribution to existing knowledge of the Pacific. Their subjects will be as varied as is the multi-disciplinary interests of the Program and the wealth of cooperation received from the many Pacific-interested members of the University faculty and the cooperating com munity. Pacific Islands Program Room 5, George Hall Annex 8 University of Hawaii • PRELIMINARY / BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE MATERIALS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII, MANOA CAMPUS Compiled by Nancy Jane Morris Verna H. F. Young Kehau Kahapea Velda Yamanaka , . • Revised 1974 Second Printing, 1979 PREFACE The Hawaiian Collection of the University of Hawaii Library is perhaps the world's largest, numbering more than 50,000 volumes. As students of the Hawaiian language, we have a particular interest in the Hawaiian language texts in the Collection. Up to now, however, there has been no single master list or file through which to gain access to all the Hawaiian language materials. This is an attempt to provide such list. We culled the bibliographical information from the Hawaiian Collection Catalog and the Library she1flists. We attempted to gather together all available materials in the Hawaiian language, on all subjects, whether imprinted on paper or microfilm, on tape or phonodisc. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

U·M·I University Microfilms International a Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adverselyaffect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrightmaterial had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9429649 Subversive dialogues: Melville's intertextual strategies and nineteenth-century American ideologies Shin, Moonsu, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 V·M·I 300 N. -

Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons All Theses & Dissertations Student Scholarship 2014 Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840 Anatole Brown MA University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd Part of the Other American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Anatole MA, "Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840" (2014). All Theses & Dissertations. 62. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd/62 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL ENCOUNTERS AND THE MISSIONARY POSITION: NEW ENGLAND’S SEXUAL COLONIZATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, 1778–1840 ________________________ A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF THE ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE AMERICAN AND NEW ENGLAND STUDIES BY ANATOLE BROWN _____________ 2014 FINAL APPROVAL FORM THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE AMERICAN AND NEW ENGLAND STUDIES June 20, 2014 We hereby recommend the thesis of Anatole Brown entitled “Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England’s Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778 – 1840” Be accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Professor Ardis Cameron (Advisor) Professor Kent Ryden (Reader) Accepted Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has been churning in my head in various forms since I started the American and New England Studies Masters program at The University of Southern Maine. -

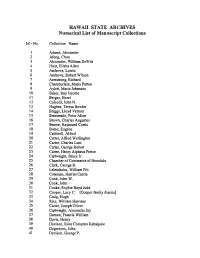

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

Commemorating the Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial

Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial Commemorating the Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th-century in the United States. During this time, several missionary societies were formed. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was organized under Calvinist ecumenical auspices at Bradford, Massachusetts, on the June 29, 1810. The first of the missions of the ABCFM were to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and India, as well as to the Cherokee and Choctaw of the southeast US. In October 1816, the ABCFM established the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, CT, for the instruction of native youth to become missionaries, physicians, surgeons, schoolmasters or interpreters. By 1817, a dozen students, six of them Hawaiians, were training at the Foreign Mission School to become missionaries to teach the Christian faith to people around the world. One of those was ʻŌpūkahaʻia, a young Hawaiian who came to the US in 1809, who was being groomed to be a key figure in a mission to Hawai‘i. ʻŌpūkahaʻia yearned “with great earnestness that he would (return to Hawaiʻi) and preach the Gospel to his poor countrymen.” Unfortunately, ʻŌpūkahaʻia died unexpectedly at Cornwall on February 17, 1818. The life and memoirs of ʻŌpūkahaʻia inspired other missionaries to volunteer to carry his message to the Hawaiian Islands. On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of ABCFM missionaries from the northeast US, set sail on the Thaddeus for the Hawaiian Islands. They first sighted the Islands and arrived at Kawaihae on March 30, 1820, and finally anchored at Kailua-Kona, April 4, 1820. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Mission Stations

Mission Stations The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), based in Boston, was founded in 1810, the first organized missionary society in the US. One hundred years later, the Board was responsible for 102-mission stations and a missionary staff of 600 in India, Ceylon, West Central Africa (Angola), South Africa and Rhodesia, Turkey, China, Japan, Micronesia, Hawaiʻi, the Philippines, North American native American tribes, and the "Papal lands" of Mexico, Spain and Austria. On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of ABCFM missionaries set sail on the Thaddeus to establish the Sandwich Islands Mission (now known as Hawai‘i). Over the course of a little over 40-years (1820- 1863 - the “Missionary Period”), about 180-men and women in twelve Companies served in Hawaiʻi to carry out the mission of the ABCFM in the Hawaiian Islands. One of the earliest efforts of the missionaries, who arrived in 1820, was the identification and selection of important communities (generally near ports and aliʻi residences) as “Stations” for the regional church and school centers across the Hawaiian Islands. As an example, in June 1823, William Ellis joined American Missionaries Asa Thurston, Artemas Bishop and Joseph Goodrich on a tour of the island of Hawaiʻi to investigate suitable sites for mission stations. On O‘ahu, locations at Honolulu (Kawaiahaʻo), Kāne’ohe, Waialua, Waiʻanae and ‘Ewa served as the bases for outreach work on the island. By 1850, eighteen mission stations had been established; six on Hawaiʻi, four on Maui, four on Oʻahu, three on Kauai and one on Molokai. Meeting houses were constructed at the stations, as well as throughout the district.