A Systems Inquiry Into Organizational Learning for Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social System of Systems Intelligence – a Study Based on Search Engine Method

In Essays on Systems Intelligence, eds. Raimo P. Hämäläinen and Esa Saarinen: pp. 119-133 Espoo: Aalto University, School of Science and Technology, Systems Analysis Laboratory Chapter 5 The Social System of Systems Intelligence – A Study Based on Search Engine Method Kalevi Kilkki This essay offers an preliminary study on systems intelligence as a social system based on four cornerstones: writings using the terminology of systems intelligence, search engines, models to describe the behavior of social phenomena, and a theory of social systems. As a result we provide an illustration of systems intelligence field as a network of key persons. The main conclusion is that the most promising area for systems intelligence as social system is to systematically apply positive psychology to develop organizational management and to solve our everyday problems. Introduction The social system of systems intelligence is an ambitious topic, particularly for a person without any formal studies in sociology. Moreover, systems intelligence is a novel area of science and, hence, the development of its social structures is in early phase. It is even possible to argue that there is not yet any social system of systems intelligence. The approach of this study is based on four cornerstones: first, the literature that has used concept of systems intelligence, second, search engines, third, models to describe the behavior of social phenomena, and forth, a theory of social systems. As a result we may be able to say something novel about the development of systems intelligence as a social system. As to the social systems this essay relies on the grand theory developed by Niklas Luhmann (Luhmann 1995). -

What Is Systems Theory?

What is Systems Theory? Systems theory is an interdisciplinary theory about the nature of complex systems in nature, society, and science, and is a framework by which one can investigate and/or describe any group of objects that work together to produce some result. This could be a single organism, any organization or society, or any electro-mechanical or informational artifact. As a technical and general academic area of study it predominantly refers to the science of systems that resulted from Bertalanffy's General System Theory (GST), among others, in initiating what became a project of systems research and practice. Systems theoretical approaches were later appropriated in other fields, such as in the structural functionalist sociology of Talcott Parsons and Niklas Luhmann . Contents - 1 Overview - 2 History - 3 Developments in system theories - 3.1 General systems research and systems inquiry - 3.2 Cybernetics - 3.3 Complex adaptive systems - 4 Applications of system theories - 4.1 Living systems theory - 4.2 Organizational theory - 4.3 Software and computing - 4.4 Sociology and Sociocybernetics - 4.5 System dynamics - 4.6 Systems engineering - 4.7 Systems psychology - 5 See also - 6 References - 7 Further reading - 8 External links - 9 Organisations // Overview 1 / 20 What is Systems Theory? Margaret Mead was an influential figure in systems theory. Contemporary ideas from systems theory have grown with diversified areas, exemplified by the work of Béla H. Bánáthy, ecological systems with Howard T. Odum, Eugene Odum and Fritj of Capra , organizational theory and management with individuals such as Peter Senge , interdisciplinary study with areas like Human Resource Development from the work of Richard A. -

Strategy+Business Issue 40 Works on His Most Ambitious Computer Model: a General Such Complacency

strate gy+business The Prophet of Unintended Consequences by Lawrence M. Fisher from strate gy+business issue 40, Autumn 2005 reprint number 05308 Reprint f e a t u r e s The Prophet of t h e c r e a t i v e m Unintended i n d Consequences 1 by Lawrence M. Fisher Jay Forrester’s computer models show the nonlinear roots of calamity and reveal the leverage that can help us avoid it. Photographs by Steve Edson d n i m e v i t a e r c e h t s e r u t a e 2 f Lawrence M. Fisher ([email protected]), a contributing editor to strategy+ business, covered technology for the New York Times for 15 years and has written for dozens of other business publications. Mr. Fisher is based in San Francisco. A visitor traveling from Boston to Jay Forrester’s maintain its current weight, producing cravings for fat- f home in the Concord woods must drive by Walden tening food. Similarly, a corporate reorganization, how- e a Pond, where the most influential iconoclast of American ever well designed, tends to provoke resistance as t u r literature spent an insightful couple of years. Jay employees circumvent the new hierarchy to hang on to e s Forrester, the Germeshausen Professor Emeritus of their old ways. To Professor Forrester, these kinds of dis- t h e Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Tech- comfiting phenomena are innate qualities of systems, c nology’s Sloan School of Management, also has a repu- and they routinely occur when people try to instill ben- r e a tation as an influential and controversial iconoclast, at eficial change. -

Communities of Commitment: the Heart of Learning Organizations

Work at the MIT Center for Organizatiotial Learning shows that developing new organizational capabilities requires deep reflection and testing. Communities of Commitment: The Heart of Learning Organizations FRED KOFMAN PETER M. SENGE hy do we confront learning opportuni- breakthroughs via partnership between re- W ties witb fear rather than wonder? Why searchers and practitioners. do we derive our self-esteem from knowing Two years of intense practice and reflec- as opposed to learning? Why do we criticize tion have gone by. Some pilot projects are be- before we even understand? Why do we cre- ginning to produce striking results. But we ate controlling bureaucracies when we at- also have learned that it is crucial to address tempt to form visionary enterprises? And the opening questions. We have not found why do we persist in fragmentation and any definitive answers—nor were we looking piecemeal analysis as the world becomes for them—but, dwelling in the questions, we more and more interconnected? have found guiding principles for action. Such questions have been the heart of our Building learning organizations, we are work for many years. They led to the theories discovering, requires basic shifts in how we and methods presented in The Fifth Disciptine. think and interact. The changes go beyond in- They are the driving force behind a new vi- dividual corporate cultures, or even the cul- sion of organizations, capable of thriving in a ture of Western management; they penetrate world of interdependence and change—what to the bedrock assumptions and habits of our we have come to call "learning organiza- culture as a whole. -

MANAGEMENT GURUS and MANAGEMENT FASHIONS: a DRAMATISTIC INQUIRY a Thesis in Support of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D

MANAGEMENT GURUS AND MANAGEMENT FASHIONS: A DRAMATISTIC INQUIRY A thesis in support of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) By Bradley Grant Jackson, B.Sc., M.A. Department of Management Learning The Management School Lancaster University November 28,1999 JUN 2000 ProQuest Number: 11003637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003637 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Since the 1980s, popular management thinkers, or management gurus, have promoted a number of performance improvement programs or management fashions that have greatly influenced both the pre-occupations of academic researchers and the everyday conduct of organizational life. This thesis provides a rhetorical critique of the management guru and management fashion phenomenon with a view to building on the important theoretical progress that has recently been made by a small, but growing, band of management researchers. Fantasy theme analysis, a dramatistically-based method of rhetorical criticism, is conducted on three of the most important management fashions to have emerged during the 1990s: the reengineering movement promoted by Michael Hammer and James Champy; the effectiveness movement led by Stephen Covey; and the learning organization movement inspired by Peter Senge and his colleagues. -

The Talking Cure Cody CH 2014

Complexity, Chaos Theory and How Organizations Learn Michael Cody Excerpted from Chapter 3, (2014). Dialogic regulation: The talking cure for corporations (Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Law. University of British Columbia). Available at: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0077782 Most people define learning too narrowly as mere “problem-solving”, so they focus on identifying and correcting errors in the external environment. Solving problems is important. But if learning is to persist, managers and employees must also look inward. They need to reflect critically on their own behaviour, identify the ways they often inadvertently contribute to the organisation’s problems, and then change how they act. Chris Argyris, Organizational Psychologist Changing corporate behaviour is extremely meet expectations120; difficult. Most corporate organizational change • 15% of IT projects are successful121; programs fail: planning sessions never make it into • 50% of firms that downsize experience a action; projects never quite seem to close; new decrease in productivity instead of an rules, processes, or procedures are drafted but increase122; and people do not seem to follow them; or changes are • Less than 10% of corporate training affects initially adopted but over time everything drifts long-term managerial behaviour.123 back to the way that it was. Everyone who has been One organization development OD textbook involved in managing or delivering a corporate acknowledges that, “organization change change process knows these scenarios -

A Complex Systems Framework for Research on Leadership and Organizational Dynamics in Academic Libraries

Wichita State University Libraries SOAR: Shocker Open Access Repository Donald L. Gilstrap University Libraries A Complex Systems Framework for Research on Leadership and Organizational Dynamics in Academic Libraries Donald L. Gilstrap Wichita State University Citation Gilstrap, Donald L. 2009. A complex systems framework for research on leadership and organizational dynamics in academic libraries -- portal: Libraries and the Academy, v.9 no.1, January 2009 pp. 57-77 | 10.1353/pla.0.0026 The definitive version of this paper is posted in the Shocker Open Access Repository with the publisher’s permission: http://soar.wichita.edu/handle/10057/6639 Donald L. Gilstrap 57 A Complex Systems Framework for Research on Leadership and Organizational Dynamics in Academic Libraries Donald L. Gilstrap abstract: This article provides a historiographical analysis of major leadership and organizational development theories that have shaped our thinking about how we lead and administrate academic libraries. Drawing from behavioral, cognitive, systems, and complexity theories, this article discusses major theorists and research studies appearing over the past century. A complex systems framework is then proposed for future research on leadership and organizational development surrounding change in academic libraries and professional responsibilities. Introduction n 2002, this journal was nearing the end of its second volume. The editor challenged our profession to ask, “When’s this paradigm shift ending?” In order to answer this question, Charles B. Lowry performed a recursive history, weaving together the ma- Ijor impacts on academic librarians during the course of a century and a half.1 Granted, we have probably seen some of the most significant of these changes take place in our libraries over the past 20 years as a result of digital and networked technologies, but Lowry’s challenge to us all was to examine our environments and determine whether current practices and structures were suited for future development. -

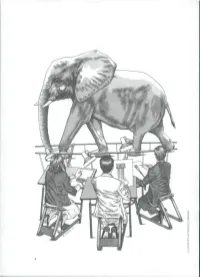

The Systems Thinking School Leading Systematic School Improvement

The Systems Thinking School Leading Systematic School Improvement Titles in the Series Thinkers in Action: A Field Guide for Effective Change Leadership in Education Systems Thinkers in Action: A Field Guide for Effective Change Leadership in Education Moving Upward Together: Creating Strategic Alignment to Sustain Systemic School Im- provement How to Get the Most Reform for Your Reform Money Future Search in School District Change: Connection, Community, and Results Instructional Leadership for Systemic Change: The Story of San Diego's Reform Dream! Create! Sustain!: Mastering the Art and Science of Transforming School Systems Leading from the Eye of the Storm: Spirituality and Public School Improvement Power, Politics, and Ethics in School Districts: Dynamic Leadership for Systemic Change The Future of Schools: How Communities and Staff Can Transform Their School Districts Priority Leadership: Generating School and District Improvement through Systemic Change Strategic Communication During Whole-System Change: Advice and Guidance for School District Leaders and PR Specialists Toys, Tools & Teachers: The Challenges of Technology Curriculum and Assessment Policy: 20 Questions for Board Members Adventures of Charter School Creators: Leading from the Ground Up Leaders Who Win, Leaders Who Lose: The Fly-on-the-Wall Tells All The Positive Side of Special Education: Minimizing Its Fads, Fancies, and Follies The Systems Thinking School: Redesigning Schools from the Inside-Out The Systems Thinking School Redesigning Schools from the Inside-Out Peter A. Barnard ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD EDUCATION A division of ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK Published by Rowman & Littlefield Education A division of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. -

Knowledge Management This Page Intentionally Left Blank Knowledge Management Classic and Contemporary Works

Knowledge Management This page intentionally left blank Knowledge Management Classic and Contemporary Works Edited by Daryl Morey Mark Maybury Bhavani Thuraisingham The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2000 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or informa- tion storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Sabon by Mary Reilly Graphics. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Knowledge management : classic and contemporary works / edited by Daryl Morey, Mark Maybury, Bhavani Thuraisingham. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-133384-9 (hc.) 1. Knowledge management. I. Morey, Daryl. II. Maybury, Mark T. III. Thuraisingham, Bhavani M. HD30.2 .K63686 2001 658.4'038—dc21 00-046042 For their generous support, this collection is dedicated to our spouses Ellen, Michelle, and Thevendra This page intentionally left blank Contents Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Introduction: Can Knowledge Management Succeed Where Other Efforts Have Failed? 1 Margaret Wheatley I Strategy Introduction: Strategy: Compelling Word, Complex Concept 11 Gordon Petrash 1 Classic Work: The Leader’s New Work: Building Learning Organizations 19 Peter Senge 2 Reflection on “A Leader’s New Work: Building Learning Organizations” 53 Peter Senge 3 Developing a Knowledge Strategy: From -

Introducing System Dynamics and Systems Thinking to a School (Or Children) Near You

System Dynamics Our mission is to develop Systems & Systems Citizens in K-12 education who use Systems Thinking in Thinking and System Dynamics to meet the K-12 Education interconnected challenges that face them at personal, community, and global levels. www.clexchange.org II Dollars SenseOur Interest and in Interest By Jeff Potash Illustrations by Nathan Walker Introducing System Dynamics and Systems Thinking to a School (or Children) Near You A packet of materials designed to help those conversant with system dynamics become involved with the education of students ages 3-19 For more information, conversation or help: Lees Stuntz ([email protected]) Anne LaVigne ([email protected]) Contents of this booklet: 1. CLE brochure- These are useful to hand out to interested educators and citizen champions. It incorporates explanations of how ST/SD address the Common Core State Standards as well as the STEM process standards, both preeminent concerns of educators currently. 2. Introduction 3. List of resources including resources, books and articles from the Creative Learning Exchange and other places. 4. List of CLE products 5. Characteristics of Complex Systems introduction page 6. Habits page – An illustrated list of the Habits of a Systems Thinker from the Waters Foundation 7. Indicators of readiness for schools and districts put together by the experienced mentors from the Systems Thinking in Schools Project of the Waters Foundation. Suggested Creative Learning Exchange Materials for your own perusal and to give to teachers and schools: • Shape of Change including Stocks and Flows • Dollars and Sense: Stay in the Black, Spending and Saving • Critical Thinking Using Systems Thinking and Dynamic Modeling • CD containing all of the materials available on the Creative Learning Exchange website. -

All Models Are Wrong: Reflections on Becoming a Systems Scientist†

All models are wrong: reflections on becoming a systems scientist† John D. Sterman* Jay Wright Forrester Prize Lecture, 2002 John D. Sterman is Abstract the J. Spencer Standish Professor of Thoughtful leaders increasingly recognize that we are not only failing to solve the persistent Management and problems we face, but are in fact causing them. System dynamics is designed to help avoid such Director of the System policy resistance and identify high-leverage policies for sustained improvement. What does it Dynamics Group at take to be an effective systems thinker, and to teach system dynamics fruitfully? Understanding the MIT Sloan School complex systems requires mastery of concepts such as feedback, stocks and flows, time delays, of Management. and nonlinearity. Research shows that these concepts are highly counterintuitive and poorly understood. It also shows how they can be taught and learned. Doing so requires the use of formal models and simulations to test our mental models and develop our intuition about complex systems. Yet, though essential, these concepts and tools are not sufficient. Becoming an effective systems thinker also requires the rigorous and disciplined use of scientific inquiry skills so that we can uncover our hidden assumptions and biases. It requires respect and empathy for others and other viewpoints. Most important, and most difficult to learn, systems thinking requires understanding that all models are wrong and humility about the limitations of our knowledge. Such humility is essential in creating an environment in which we can learn about the complex systems in which we are embedded and work effectively to create the world we truly desire. -

Chaos As Creativity Catherine E

Western University Scholarship@Western Western Libraries eBook Collection eBook Collections 2018 Chaos as Creativity Catherine E. Wilkins University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/wlbooks Recommended Citation Wilkins, Catherine E., "Chaos as Creativity" (2018). Western Libraries eBook Collection. 1. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/wlbooks/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the eBook Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western Libraries eBook Collection by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Chaos as Creativity Catherine E. Wilkins Western University This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. ISBN number: 978-0-7714-3113-5 “When you arise in the morning, think of what precious privilege it is to be alive – to breathe, to think, to enjoy, to love.” Marcus Aurelius About the Author Catherine Wilkins is inspired by the collegial culture of Western Libraries and Western University. She provided leadership for The D.B. Weldon Library 2006-2018 and is now Librarian Emeritus. In her role at Western she worked collaboratively with colleagues and students on a variety of strategic library initiatives, was elected to Senate and actively served on numerous University Committees. Catherine holds a BMus (Western), MLS (Western), MEd (Toronto), Ed D (Toronto).