Full Version of the Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Returnee Monitoring Study Minority Returnees to the Republika Srpska - Bosnia and Herzegovina UNHCR Sarajevo June 2000 This study was researched and written by Michelle Alfaro, with the much appreciated assistance and support of Snjezana Ausic, Zoran Beric, Ranka Bekan-Cihoric, Jadranko Bijelica, Sanja Kljajic, Renato Kunstek, Nefisa Medosevic, Svjetlana Pejdah, Natasa Sekularac, Maja Simic, and Alma Zukic, and especially Olivera Markovic. For their assistance with conducting interviews, we are grateful to BOSPO, a Tuzla NGO, and IPTF and OSCE in Prijedor Municipality. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION UNHCR conducted a Returnee Monitoring Framework (RMF) study in the Republika Srpska (RS) between 5 January and 3 March 2000. A total of 194 interviews were carried out, covering 30 villages or towns within 12 municipalities, with minority returnees to the RS who had either fully returned or were in the process of return. The purpose of the this study was to gauge the national protection afforded to minority returnees to the RS, the living conditions of returnees, as well as the positive and negative factors which affect the sustainability of return. For example, interviewees were asked questions about security, schools, pensions, health care, etc. Through the 194 interviews, UNHCR was able to obtain information on 681 persons. Broken down by ethnicity, there were 657 Bosniacs, 13 Bosnian Croats, and 11 Other which included Serbs in mixed marriages, people of mixed ethnicity and several people of other nationalities who had immigrated to BH before the conflict. 20% of the study group was over 60 years old (elderly), 54% was between the ages of 19-59, 20% was school age (7-18 years), and 6% was 0-6 years old. -

FIRST PRELIMINARY REPORT on LONG-TERM ELECTION OBSERVATION (Covering the Period 23.07

FIRST PRELIMINARY REPORT ON LONG-TERM ELECTION OBSERVATION (covering the period 23.07. – 02.09.2018) September 2018 Table of Contents 1. Report summary 2. Long-term election observation methodology 3. About the 2018 General Elections 3.1. The 2018 General Elections in short 3.2. What are the novelties at the 2018 General Elections? 4. Long-term election observation 4.1. Electoral irregularities 4.1.1. Premature election campaign 4.1.2. Maintenance of the up-to-date Central Voters Register (CVR) 4.1.3. Illegal trading of seats on the polling station committees 4.1.4. Abuse of personal information for voter registration 4.1.5. Voter coercion and/or vote buying 4.1.6. Abuse of public resources and public office for campaigning purposes 4.1.7. Other irregularities 4.2. Work of the election administration 4.2.1. BiH Central Election Commission (1) 4.2.2. Local Election Commissions (143) 4.3. Media, civil society and the citizens 4.3.1. Media reporting 4.3.2. Civil Society and the citizens 5. About the Coalition “Pod lupom” The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Coalition “Pod lupom” and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Coalition “Pod lupom” and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID or the United States Government. 2 1. Report Summary About the 2018 General Elections - The 2018 General Elections are scheduled for Sunday, 7th October 2018 and are called for 6 levels, i.e. -

The Law Amending the Law on the Courts of The

LAW AMENDING THE LAW ON COURTS OF THE REPUBLIKA SRPSKA Article 1 In the Law on Courts of the Republika Srpska (“Official Gazette of the Republika Srpska”, No: 37/12) in Article 26, paragraph 1, lines b), e), l) and nj) shall be amended to read as follows: “b) the Basic Court in Bijeljina, for the territory of the Bijeljina city, and Ugljevik and Lopare municipalities,”, “e) the Basic Court in Doboj, for the territory of Doboj city and Petrovo and Stanari municipalities,”, “l) the Basic Court in Prijedor, for the territory of Prijedor city, and Oštra Luka and Kozarska Dubica municipalities,” and “nj) the Basic Court in Trebinje, for the territory of Trebinje city, and Ljubinje, Berkovići, Bileća, Istočni Mostar, Nevesinje and Gacko municipalities,”. Article 2 In Article 28, in line g), after the wording: “of this Law” and comma punctuation mark, the word: “and” shall be deleted. In line d), after the wording: “of this Law”, the word: “and” shall be added as well as the new line đ) to read as follows: “đ) the District Court in Prijedor, for the territories covered by the Basic Courts in Prijedor and Novi Grad, and for the territory covered by the Basic Court in Kozarska Dubica in accordance with conditions from Article 99 of this Law.” Article 3 In Article 29, line g), after the wording: “the District Commercial Court in Trebinje”, the word: “and” shall be deleted and a comma punctuation mark shall be inserted. In line d), after the wording: “the District Commercial Court in East Sarajevo”, the word: “and” shall be added as well as the -

Execution of Demining (Dem) and Technical Survey (Ts) Works

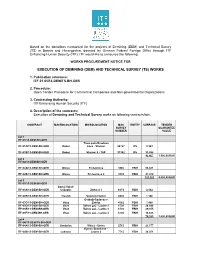

Based on the donations earmarked for the projects of Demining (DEM) and Technical Survey (TS) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, donated by German Federal Foreign Office through ITF Enhancing Human Security (ITF), ITF would like to announce the following: WORKS PROCUREMENT NOTICE FOR EXECUTION OF DEMINING (DEM) AND TECHNICAL SURVEY (TS) WORKS 1. Publication reference: ITF-01-05/13-DEM/TS-BH-GER 2. Procedure: Open Tender Procedure for Commercial Companies and Non-governmental Organizations 3. Contracting Authority: ITF Enhancing Human Security (ITF) 4. Description of the contracts: Execution of Demining and Technical Survey works on following contracts/lots: CONTRACT MACROLOCATION MICROLOCATION MAC ENTITY SURFACE TENDER SURVEY GUARANTEE NUMBER VALUE Lot 1 ITF-01/13-DEM-BH-GER Trasa puta Hrastova ITF-01A/13-DEM-BH-GER Doboj kosa - Stanovi 50767 RS 9.369 ITF-01B/13-DEM-BH-GER Doboj Stanovi 9 - TAP 51392 RS 33.098 42.467 1.500,00 EUR Lot 2 ITF-02/13-DEM-BH-GER ITF-02A/13-DEM-BH-GER Olovo Pridvornica 9386 FBiH 53.831 ITF-02B/13-DEM-BH-GER Olovo Pridvornica 5 9393 FBiH 47.470 101.301 4.000,00 EUR Lot 3 ITF-03/13-DEM-BH-GER Gornji Vakuf- ITF-03A/13-DEM-BH-GER Uskoplje Zdrimci 1 6673 FBiH 2.542 ITF-03B/13-DEM-BH-GER Travnik Vodovod Seferi 8538 FBiH 1.186 Grabalji-Sadavace- ITF-03C/13-DEM-BH-GER Vitez Zabilje 4582 FBiH 7.408 ITF-03D/13-DEM-BH-GER Vitez Šehov gaj – Lazine 2 6702 FBiH 28.846 ITF-03E/13-DEM-BH-GER Vitez Šehov gaj – Lazine 3 6703 FBiH 20.355 ITF-03F/13-DEM-BH-GER Vitez Šehov gaj – Lazine 4 6704 FBiH 18.826 79.163 3.000,00 EUR Lot 4 ITF-04/13-DEM/TS-BH-GER -

Bosnia-Herzegovina Political Briefing: BIH`S Troyka Agreement - Ambitious Or Premature Plan to Exit from 10 Months-Long Government Crisis? Ivica Bakota

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 21, No. 1 (BH) Sept 2019 Bosnia-Herzegovina political briefing: BIH`s Troyka Agreement - ambitious or premature plan to exit from 10 months-long government crisis? Ivica Bakota 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 BIH`s Troyka Agreement - ambitious or premature plan to exit from 10 months-long government crisis? Introduction On August 5, the leaders of three dominant ethno-political parties (Troyka) in rather unexpected turn signed a coalition agreement that would put an end to 10 month-long crisis in forming the central government. Bakir Izetbegovic, leader of the Democratic Action Party (SDA), Milorad Dodik, Serb Member of Presidency and Chairman of the Union of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), and Dragan Covic, leader of the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ BIH) seemed to have finally reached an agreement on the formation of the Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina, troubleshooting deadlock in the BIH Parliamentary Assembly and forming the Federal government. The Troyka Agreement was supported by the Head of Delegation of the European Union, Lars G. Wigemark and very ambitiously included a clause to form a government within a month time period from signing the agreement. As a main initiator, SNSD Chairman Milorad Dodik according to ethnic rotation key will nominate the Chairman of the Council of Ministers (COM Chairman) and also outline the distribution of the ministerial posts. Without big surprises, Zoran Tegeltija, SNSD member and RS government member, remains the sole candidate for COM Chairman, and 3 x 3 - 1 ministry allocation scheme (three ministries for each three party/ethnicities minus one ministry to “other” ethnicities) was also preliminary agreed. -

European Social Charter the Government of Bosnia And

16/06/2021 RAP/RCha/BIH/11 (2021) EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER 11th National Report on the implementation of the European Social Charter submitted by THE GOVERNMENT OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Articles 11, 12, 13, 14 and 23 of the European Social Charter for the period 01/01/2016 – 31/12/2019 Report registered by the Secretariat on 16 June 2021 CYCLE 2021 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA MINISTRY OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND REFUGEES THE ELEVENTH REPORT OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER /REVISED/ GROUP I: HEALTH, SOCIAL SECURITY AND SOCIAL PROTECTION ARTICLES 11, 12, 13, 14 AND 23 REFERENCE PERIOD: JANUARY 2016 - DECEMBER 2019 SARAJEVO, SEPTEMBER 2020 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 3 II. ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA ........... 4 III. GENERAL LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK ......................................................... 5 1. Bosnia and Herzegovina ............................................................................................... 5 2. Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina ....................................................................... 5 3. Republika Srpska ........................................................................................................... 9 4. Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovina .............................................................. 10 IV. IMPLEMENTATION OF RATIFIED ESC/R/ PROVISIONS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA .............................................................................................. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Analytical Report

Bosnia and Herzegovina Analytical Report August 2020 Table of contents Russian Influence Raises Concerns in BiH 3 1.0 Summary 3 2.0 Key Political Developments 5 2.1 Russia Uses Dodik to Tie Future of BiH and Kosovo 5 2.2 Adoption of BiH Budget Clears the Way For Local Elections 7 2.3 Bosniak Political Scene: Battle of Two Hospitals 8 3.0 Socio-Economic Developments 11 3.1 Overview 11 3.2 Latest Statistical Data 14 Foreign trade 15 Foreign Exchange Reserves 16 Banking sector 17 Inflation (CPI) 18 Industrial production 18 Employment and Unemployment 19 Wages 20 Pensions 21 Footnotes 22 2 Russian Influence Raises Concerns in BiH 1.0 Summary Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has witnessed some positive as well as negative developments over the last few months. On the one hand, BiH has found itself caught up in deepening geopolitical competition, which has been affecting the Balkans in recent months, and now seems to be getting dragged into a possible newly-created rift between Belgrade and Moscow. With his latest statements, Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik has tried to link the fates of BiH and Kosovo, threatening to push for full independence for the Republika Srpska (RS) entity if the same is granted to Kosovo. This has triggered new tensions and rebukes, mainly from Bosniak politicians and media, who repeatedly stressed that any new move for a breakup of BiH could lead to new violence, just like it did in 1991. Preoccupied with their own internal issues and focused on the restart of the EU-led dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia, EU and US diplomats have so far mainly ignored this tense public discourse. -

Electoral Processes in the Mediterranean

Electoral Processes Electoral processes in the Mediterranean This chapter provides information on jority party if it does not manage to Gorazd Drevensek the results of the presidential and leg- obtain an absolute majority in the (New Slovenia Christian Appendices islative elections held between July Chamber. People’s Party, Christian Democrat) 0.9 - 2002 and June 2003. Jure Jurèek Cekuta 0.5 - Parties % Seats Participation: 71.3 % (1st round); 65.2 % (2nd round). Monaco Nationalist Party (PN, conservative) 51.8 35 Legislative elections 2003 Malta Labour Party (MLP, social democrat) 47.5 30 9th February 2003 Bosnia and Herzegovina Med. Previous elections: 1st and 8th Februa- Democratic Alternative (AD, ecologist) 0.7 - ry 1998 Federal parliamentary republic that Parliamentary monarchy with unicam- Participation: 96.2 %. became independent from Yugoslavia eral legislative: the National Council. in 1991, and is formed by two enti- The twenty-four seats of the chamber ties: the Bosnia and Herzegovina Fed- Slovenia are elected for a five-year term; sixteen eration, known as the Croat-Muslim Presidential elections by simple majority and eight through Federation, and the Srpska Republic. 302-303 proportional representation. The voters go to the polls to elect the 10th November 2002 Presidency and the forty-two mem- Previous elections: 24th November bers of the Chamber of Representa- Parties % Seats 1997 tives. Simultaneously, the two entities Union for Monaco (UPM) 58.5 21 Parliamentary republic that became elect their own legislative bodies and National Union for the Future of Monaco (UNAM) independent from Yugoslavia in 1991. the Srpska Republic elects its Presi- Union for the Monegasque Two rounds of elections are held to dent and Vice-President. -

Pregled Poreznih Obveznika Sa Iznosom Duga Po Osnovu Poreza, Doprinosa, Taksi I Drugih Naknada Preko 50.000,00 Km Na Dan 31.12. 2019. Godine

PREGLED POREZNIH OBVEZNIKA SA IZNOSOM DUGA PO OSNOVU POREZA, DOPRINOSA, TAKSI I DRUGIH NAKNADA PREKO 50.000,00 KM NA DAN 31.12. 2019. GODINE SJEDIŠTE KANTONALNI SALDO DUGA NA R/B ID BROJ POREZNOG POREZNI IZNOS DUGA DAN 31.12. 2019. NAZIV POREZNOG OBVEZNIKA OBVEZNIKA URED GLAVNICA KAMATA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8(6+7) 1 JP "ŽELJEZNICE FBIH" 4200450270001 SARAJEVO SARAJEVO 186.351.101,05 13.129.773,84 199.480.874,89 2 JP "EPBIH" DD - ZD RMU "ZENICA" DOO 4218116700000 ZENICA ZENICA 126.373.906,20 13.342.873,54 139.716.779,74 3 KJKP "GRAS" DOO 4200055640002 SARAJEVO SARAJEVO 91.723.071,69 39.989.080,12 131.712.151,81 4 JP "EPBIH" DD - ZD RUDNICI "KREKA" DOO 4209020780003 TUZLA TUZLA 127.500.926,40 3.442.600,52 130.943.526,92 5 JP "EPBIH" DD - ZD RMU "BREZA" DOO 4218303300007 BREZA ZENICA 78.154.961,78 1.909.507,65 80.064.469,43 6 SVEUČILIŠNA KLINIČKA BOLNICA MOSTAR 4227224680006 MOSTAR MOSTAR 62.506.485,06 9.194.417,99 71.700.903,05 7 JP "EPBIH" DD - ZD RMU "KAKANJ" DOO 4218055050007 KAKANJ ZENICA 68.187.205,70 938.571,28 69.125.776,98 8 "HIDROGRADNJA" DD (STEČAJ) 4200315570003 SARAJEVO SARAJEVO 41.998.309,78 24.639.343,77 66.637.653,55 9 JP "AUTOCESTE FEDERACIJE BIH" DOO 4227691540005 MOSTAR MOSTAR 36.414.740,58 24.819.542,49 61.234.283,07 10 ŽELJEZARA "ZENICA" DOO (STEČAJ) 4218009370005 ZENICA ZENICA 29.888.954,97 24.265.076,17 54.154.031,14 VELIKA 11 "AGROKOMERC" DD 4263179080007 BIHAĆ 30.076.050,48 10.566.425,54 40.642.476,02 KLADUŠA 12 JP "EPBIH" DD - ZD RMU "ABID LOLIĆ" DOO 4236078160002 TRAVNIK NOVI TRAVNIK 31.745.372,86 6.158.050,52 37.903.423,38 -

Itf-01-09/17-Dem/Ts-Bh-Usa

Based on the donations earmarked for the projects of Demining (DEM) and Technical Survey (TS) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, donated by Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement in the U. S. Department of State’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs through ITF Enhancing Human Security (ITF), ITF would like to announce the following: WORKS PROCUREMENT NOTICE FOR EXECUTION OF DEMINING (DEM) AND TECHNICAL SURVEY (TS) WORKS 1. Publication reference: ITF-01-09/17-DEM/TS-BH-USA 2. Procedure: Open Tender Procedure for Commercial Companies and Non-governmental Organizations 3. Contracting Authority: ITF Enhancing Human Security (ITF) 4. Description of the contracts: Execution of Demining works on following contracts: ITF-01-03/17-DEM-BH-USA CONTRACT MACROLOCATION MICROLOCATION MAC ENTITY SURFACE TENDER SURVEY GUARANTEE NUMBE VALUE R ITF-01/17-DEM-BH-USA ITF-01A/17-DEM-BH-USA Doboj-Istok Lukavica Rijeka -Sofici 7625 FBiH 15.227 ITF-01B/17-DEM-BH-USA Orasje Kanal Vidovice 7673 FBiH 4.228 ITF-01C/17-DEM-BH-USA Lukavac Savičići 1B - Luka 10724 FBiH 6.285 ITF-01D/17-DEM-BH-USA Derventa Seoski put Novi Luzani-nastavak 53368 RS 5.769 31.509 1.300,00 USD ITF-02/17-DEM -BH-USA ITF-02A/17-DEM-BH-USA Olovo Olovske Luke 10403 FBiH 1.744 ITF-02B/17-DEM-BH-USA Visoko Catici 1 10010 FBiH 19.340 21.084 900,00 USD ITF-03/17-DEM -BH-USA ITF-03/17-DEM-BH-USA Krupa na Uni Srednji Dubovik 1 53053 RS 29.135 29.135 1.200,00 USD ITF-01-03/17-DEM -BH-USA TOTAL DEM 7 81.728 Execution of Technical Survey works on following contract: ITF-01-09/17-TS-BH-USA CONTRACT MACROLOCATION -

Bosnia's Future

Bosnia’s Future Europe Report N°232 | 10 July 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Quest for Identity ...................................................................................................... 5 III. A Patronage Economy ...................................................................................................... 11 A. The Sextet ................................................................................................................... 11 B. The Economic Paradox .............................................................................................. 13 C. Some Remedies .......................................................................................................... 15 IV. The Trouble with the Entities ........................................................................................... 17 A. Ambivalence in the Federation .................................................................................. 18 B. Republika Srpska’s High-Stakes Gamble -

NEWSLETTER NATO/Pfp Trust Fund Programme for Assistance to Redundant Personnel in Bosnia and Herzegovina

NEWSLETTER NATO/PfP Trust Fund Programme for Assistance to Redundant Personnel in Bosnia and Herzegovina Newsletter Issue No. 16 - May 2009 The NATO/PfP Trust Fund is set up by NATO Member States and other donors to assist Bosnia Contents: and Herzegovina with the reintegration of personnel made redundant through the Defence Reform process. The NATO Trust Fund for BiH will contribute to the overall objectives of 1 Overview / Statistical BiH to maintain peace and stability, foster economic recovery, reduce unemployment and Update generate income by facilitating the resettlement into civilian and economic life of persons discharged in the course of the BiH defence reform process of 2006-2007, and those previ- 2 Stories from the Field ously downsized in 2004. 3 Spotlight on Training IOM has worldwide experience (including the implementation of a BiH’s Transitional Assis- 4 Message from the MoD tance to Demobilised Soldiers (TADS) project between 2002 and 2006) in assisting personnel affected by military downsizing to reintegrate into civilian life through job placement, Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) startup and expansion, agricultural revitalization and vocational and business training. This expertise has led IOM to becoming the executing agent also in BiH. NTF BENEFICIARIES & PROJECTS DIRECT ASSISTANCE As at April 30, 2009 a total of 2,894 redundant MoD 2,781 redundant MoD personnel have been contacted by personnel have registered with the International IOM and requested to provide supporting documentation Organization for Migration (IOM). 2,594 beneficiaries related to their reintegration expectations. Since the are redundant personnel from 2004 and 300 from beginning of the project, 2,635 project proposals have 2007.