A Strategy to Defeat the Islamic State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. Turkish Gendarmerie Fires Directly at Asylum-Seekers

Casualties on the Syrian Border continue to fall by the www.stj-sy.org Turkish Gendarmerie Casualties on the Syrian Border Continue to Fall by the Turkish Gendarmerie At least 12 asylum-seekers (men and women) killed and others injured by the Turkish Gendarmerie in July, August, September and October 2019 Page | 2 Casualties on the Syrian Border continue to fall by the www.stj-sy.org Turkish Gendarmerie At least, 12 men and women shot dead by the Turkish border guards (Gendarmerie) while attempting to access into Turkey illegally during July, August, September and October 2019. Turkey continues violating its international obligations, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights, by firing live bullets, beating, abusing and insulting asylum-seekers on the Syria-Turkey border. These violations have not ceased, despite dozens of appeals and many human rights reports that documented these acts since the outset of the asylum process to Turkey in 2012.1 According to victims’ relatives and witnesses who managed to access into Turkey, the Gendarmerie forces always fire live bullets on asylum-seekers and beats, tortures, insults, and uses those they caught in forced labor, and deport them back to Syria. STJ recommends that the Turkish government and the international community need to take serious steps that reduce violations against asylum seekers fleeing death, as violence and military operations continue to threaten Syrians and push them to search for a safe place to save their lives, knowing that Turkey has closed its borders with Syria since mid- August 2015, after the International Federation concluded a controversial immigration deal with Turkey that would prevent the flow of refugees to Europe.2 For the present report, STJ meets a medical worker and an asylum seeker tortured by the Turkish Gendarmerie as well as three relatives of victims who have been recently shot dead by Turkish border guards. -

QRCS Delivers Medical Aid to Hospitals in Aleppo, Idlib

QRCS Delivers Medical Aid to Hospitals in Aleppo, Idlib May 3rd, 2016 ― Doha: Qatar Red Crescent Society (QRCS) is proceeding with its support of the medical sector in Syria, by providing medications, medical equipment, and fuel to help health facilities absorb the increasing numbers of injuries, amid deteriorating health conditions countrywide due to the conflict. Lately, QRCS personnel in Syria procured 30,960 liters of fuel to operate power generators at the surgical hospital in Aqrabat, Idlib countryside. These $17,956 supplies will serve the town's 100,000 population and 70,000 internally displaced people (IDPs). In coordination with the Health Directorate in Idlib, QRCS is operating and supporting the hospital with fuel, medications, medical consumables, and operational costs. Working with a capacity of 60 beds and four operating rooms, the hospital is specialized in orthopedics and reconstructive procedures, in addition to general medicine and dermatology clinics. In western Aleppo countryside, QRCS personnel delivered medical consumables and serums worth $2,365 to the health center of Kafarnaha, to help reduce the pressure on the center's resources, as it is located near to the clash frontlines. Earlier, a needs assessment was done to identify the workload and shortfalls, and accordingly, the needed types of supplies were provided to serve around 1,500 patients from the local community and IDPs. In relation to its $200,000 immediate relief intervention launched last week, QRCS is providing medical supplies, fuel, and food aid; operating AlSakhour health center for 100,000 beneficiaries in Aleppo City, at a cost of $185,000; securing strategic medical stock for the Health Directorate; providing the municipal council with six water tankers to deliver drinking water to 350,000 inhabitants at a cost of $250,000; arranging for more five tankers at a cost of $500,000; providing 1,850 medical kits, 28,000 liters of fuel, and water purification pills; and supplying $80,000 worth of food aid. -

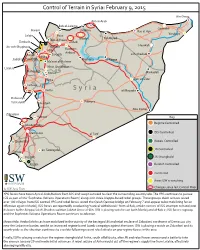

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015 Ain-Diwar Ayn al-Arab Bab al-Salama Qamishli Harem Jarablus Ras al-Ayn Yarubiya Salqin Azaz Tal Abyad Bab al-Hawa Manbij Darkush al-Bab Jisr ash-Shughour Aleppo Hasakah Idlib Kuweiris Airbase Kasab Saraqib ash-Shadadi Ariha Jabal al-Zawiyah Maskana ar-Raqqa Ma’arat al-Nu’man Latakia Khan Sheikhoun Mahardeh Morek Markadeh Hama Deir ez-Zour Tartous Homs S y r i a al-Mayadin Dabussiya Palmyra Tal Kalakh Jussiyeh Abu Kamal Zabadani Yabrud Key Regime Controlled Jdaidet-Yabus ISIS Controlled Damascus al-Tanf Quneitra Rebels Controlled as-Suwayda JN Controlled Deraa Nassib JN Stronghold Jizzah Kurdish Controlled Contested Areas ISW is watching Changes since last Control Map by ISW Syria Team YPG forces have taken Ayn al-Arab/Kobani from ISIS and swept outward to clear the surrounding countryside. The YPG continues to pursue ISIS as part of the “Euphrates Volcano Operations Room,” along with three Aleppo-based rebel groups. These groups claim to have seized over 100 villages from ISIS control. YPG and rebel forces seized the Qarah Qawzaq bridge on February 7 and appear to be mobilizing for an oensive against Manbij. ISIS forces are reportedly conducting “tactical withdrawals” from al-Bab, amidst rumors of ISIS attempts to hand over its bases to the Aleppo Sala Jihadist coalition Jabhat Ansar al-Din. ISW is placing watches on both Manbij and al-Bab as ISIS forces regroup and the Euphrates Volcano Operations Room continues to advance. Meanwhile, Hezbollah forces have mobilized in the vicinity of the besieged JN and rebel enclave of Zabadani, northwest of Damascus city near the Lebanese border, amidst an increased regime barrel bomb campaign against the town. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Army Press January 2017 Blythe

Pfc. Brandie Leon, 4th Infantry Division, holds security while on patrol in a local neighborhood to help maintain peace after recent attacks on mosques in the area, East Baghdad, Iraq, 3 March 2006. (Photo by Staff Sgt. Jason Ragucci, U.S. Army) III Corps during the Surge: A Study in Operational Art Maj. Wilson C. Blythe Jr., U.S. Army he role of Lt. Gen. Raymond Odierno’s III (MNF–I) while using tactical actions within Iraq in an Corps as Multinational Corps–Iraq (MNC–I) illustrative manner. As a result, the campaign waged by has failed to receive sufficient attention from III Corps, the operational headquarters, is overlooked Tstudies of the 2007 surge in Iraq. By far the most in this key work. comprehensive account of the 2007–2008 campaign The III Corps campaign is also neglected in other is found in Michael Gordon and Lt. Gen. Bernard prominent works on the topic. In The Gamble: General Trainor’s The Endgame: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Petraeus and the American Military Adventure in Iraq, Iraq, from George W. Bush to Barack Obama, which fo- 2006-2008, Thomas Ricks emphasizes the same levels cuses on the formulation and execution of strategy and as Gordon and Trainor. However, while Ricks plac- policy.1 It frequently moves between Washington D.C., es a greater emphasis on the role of III Corps than is U.S Central Command, and Multinational Force–Iraq found in other accounts, he fails to offer a thorough 2 13 January 2017 Army Press Online Journal 17-1 III Corps during the Surge examination of the operational campaign waged by III creating room for political progress such as the February 2 Corps. -

Counterinsurgency in the Iraq Surge

A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in US History. By Matthew T. Buchanan Director: Dr. Richard Starnes Associate Professor of History, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Committee Members: Dr. David Dorondo, History, Dr. Alexander Macaulay, History. April, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations . iii Abstract . iv Introduction . 1 Chapter One: Perceptions of the Iraq War: Early Origins of the Surge . 17 Chapter Two: Winning the Iraq Home Front: The Political Strategy of the Surge. 38 Chapter Three: A Change in Approach: The Military Strategy of the Surge . 62 Conclusion . 82 Bibliography . 94 ii ABBREVIATIONS ACU - Army Combat Uniform ALICE - All-purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment BDU - Battle Dress Uniform BFV - Bradley Fighting Vehicle CENTCOM - Central Command COIN - Counterinsurgency COP - Combat Outpost CPA – Coalition Provisional Authority CROWS- Common Remote Operated Weapon System CRS- Congressional Research Service DBDU - Desert Battle Dress Uniform HMMWV - High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle ICAF - Industrial College of the Armed Forces IED - Improvised Explosive Device ISG - Iraq Study Group JSS - Joint Security Station MNC-I - Multi-National-Corps-Iraq MNF- I - Multi-National Force – Iraq Commander MOLLE - Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment MRAP - Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (vehicle) QRF - Quick Reaction Forces RPG - Rocket Propelled Grenade SOI - Sons of Iraq UNICEF - United Nations International Children’s Fund VBIED - Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device iii ABSTRACT A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. -

Of Iraq's Kirkuk

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 392 NOVEMBER 2017 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Misen en page et maquette : Ṣerefettin ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 392 November 2017 • ROJAVA: PREPARING MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE • TURKEY: THE REPRESSION EXPANDS TO LIBER- AL CIRCLES; THE VIOLENCE IS INCREASING • IRAQI KURDISTAN: UNCONSTITUTIONAL DEMANDS FROM BAGHDAD, ARABISATION OF KIRKUK RESTARTED ROJAVA: PREPARING MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE. broad the “World Day for beginning to return to Raqqa, liber- the 17th with a suicide attack on a Kobani” was celebrated ated on 17th October. Regarding checkpoint that caused at least 35 on 1st November largely Deir Ezzor, the SDF fighters from victims in the Northeast of Deir as a symbol of this Syrian the “Jezirah Storm” operation, Ezzor Province, between the hydro- A Kurdish town’s unremit- launched on 9th September, liberated carbon fields of Conoco and Jafra. It ting resistance to the attack 7 villages near the town and about was, nevertheless, not able to pre- launched by ISIS in 2014 with fifteen km from the Iraqi borders, vent the SDF from reaching the Iraqi Turkish connivance. -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5 -

Download the Publication

Viewpoints No. 99 Mission Impossible? Triangulating U.S.- Turkish Relations with Syria’s Kurds Amberin Zaman Public Policy Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Center; Columnist, Diken.com.tr and Al-Monitor Pulse of the Middle East April 2016 The United States is trying to address Turkish concerns over its alliance with a Syrian Kurdish militia against the Islamic State. Striking a balance between a key NATO ally and a non-state actor is growing more and more difficult. Middle East Program ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ On April 7 Syrian opposition rebels backed by airpower from the U.S.-led Coalition against the Islamic State (ISIS) declared that they had wrested Al Rai, a strategic hub on the Turkish border from the jihadists. They hailed their victory as the harbinger of a new era of rebel cooperation with the United States against ISIS in the 98-kilometer strip of territory bordering Turkey that remains under the jihadists’ control. Their euphoria proved short-lived: On April 11 it emerged that ISIS had regained control of Al Rai and the rest of the areas the rebels had conquered in the past week. Details of what happened remain sketchy because poor weather conditions marred visibility. But it was still enough for Coalition officials to describe the reversal as a “total collapse.” The Al Rai fiasco is more than just a battleground defeat against the jihadists. It’s a further example of how Turkey’s conflicting goals with Washington are hampering the campaign against ISIS. For more than 18 months the Coalition has been striving to uproot ISIS from the 98- kilometer chunk of the Syrian-Turkish border that is generically referred to the “Manbij Pocket” or the Marea-Jarabulus line. -

Implementing Stability in Iraq and Syria 3

Hoover Institution Working Group on Military History A HOOVER INSTITUTION ESSAY ON THE DEFEAT OF ISIS Implementing Stability in Iraq and Syria MAX BOOT Military History The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) first captured American attention in January 2014 when its militants burst out of Syria to seize the Iraqi city of Fallujah, which US soldiers and marines had fought so hard to free in 2004. Just a few days later ISIS captured the Syrian city of Raqqa, which became its capital. At this point President Obama was still deriding it as the “JV team,” hardly comparable to the varsity squad, al-Qaeda. It became harder to dismiss ISIS when in June 2014 it conquered Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, and proclaimed an Islamic State under its “caliph,” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. With ISIS executing American hostages, threatening to massacre Yazidis trapped on Mount Sinjar, and even threatening to invade the Kurdish enclave in northern Iraq, President Obama finally authorized air strikes against ISIS beginning in early August 2014. This was soon followed by the dispatch of American troops to Iraq and then to Syria to serve as advisers and support personnel to anti-ISIS forces. By the end of September 2016, there were more than five thousand US troops in Iraq and three hundred in Syria.1 At least those are the official figures; the Pentagon also sends an unknown number of personnel, numbering as many as a few thousand, to Iraq on temporary deployments that don’t count against the official troop number. The administration has also been cagey about what mission the troops are performing; although they are receiving combat pay and even firing artillery rounds at the enemy, there are said to be no “boots on the ground.” The administration is more eager to tout all of the bombs dropped on ISIS; the Defense Department informs us, with impressive exactitude, that “as of 4:59 p.m. -

Kata'ib Sayyid Al Shuhada

Kata’ib Sayyid al Shuhada Name: Kata’ib Sayyid al Shuhada Type of Organization: Militia political party religious social services provider terrorist transnational violent Ideologies and Affiliations: Iranian-sponsored Shiite Jihadist Khomeinist Place of Origin: Iraq Year of Origin: 2013 Founder(s): Abu Mustafa al Sheibani Places of Operation: Iraq, Syria Overview Also Known As Kata’ib Abu Fadl al-Abbas1 Kata’ib Karbala2 Battalion of the Sayyid’s Martyrs3 Executive Summary Kata’ib Sayyid al Shuhada (KSS) is an Iraqi militia that has fought in both Iraq and Syria and is closely connected to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Houthis.4 Its leader is Abu Mustafa al Sheibani, a U.S.-designated terrorist who also assisted in forming the IRGC-backed Asaib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) and Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH) militias.5 The group was founded in 2013. Its first public announcements were three martyrdom notices for members killed fighting in southern Damascus alongside Syrian regime forces.6 In Syria, KSS operates within the fold of the mixed Syrian and Iraqi Liwa Abu Fadl al-Abbas, another Iranian- backed militia.7 KSS follows the same Shiite jihadist ideology as fellow pro-Iranian Iraqi militias, framing its fight in Syria as a defense of Shiites and the Shiite shrine of Sayyida Zaynab.8 In a 2013 interview, KSS’s information office stated that the group sent 500 militants to Syria.9 Other media Kata’ib Sayyid al Shuhada statements have affirmed the presence of KSS fighters in rural Damascus along the frontlines in eastern Ghouta.10 The Associated Press has reported that KSS fighters enter Syria via Iran.11 In 2015, KSS declared Saudi Arabia “a legitimate and permissible target” after that country executed a prominent Shiite cleric.12 A 2018 KSS statement indicated the group was ready to send fighters to Yemen.