Syria: Playing Into Their Hands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Access Resource

The State of Justice Syria 2020 The State of Justice Syria 2020 Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) March 2020 About the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre The Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) strives to prevent impunity, promote redress, and facilitate principled reform. SJAC works to ensure that human rights violations in Syria are comprehensively documented and preserved for use in transitional justice and peace-building. SJAC collects documentation of violations from all available sources, stores it in a secure database, catalogues it according to human rights standards, and analyzes it using legal expertise and big data methodologies. SJAC also supports documenters inside Syria, providing them with resources and technical guidance, and coordinates with other actors working toward similar aims: a Syria defined by justice, respect for human rights, and rule of law. Learn more at SyriaAccountability.org The State of Justice in Syria, 2020 March 2020, Washington, D.C. Material from this publication may be reproduced for teach- ing or other non-commercial purposes, with appropriate attribution. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for commercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Cover Photo — A family flees from ongoing violence in Idlib, Northwest Syria. (C) Lens Young Dimashqi TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Introduction 4 Major Violations 7 Targeting of Hospitals and Schools 8 Detainees and Missing Persons 8 Violations in Reconciled Areas 9 Property Rights -

Autocatalytic Models of Counter-Terrorism in East and Southeast Asia: an International Comparative Analysis of China, Indonesia, and Thailand

\\jciprod01\productn\J\JLE\50-3\JLE301.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-JUN-18 10:37 AUTOCATALYTIC MODELS OF COUNTER-TERRORISM IN EAST AND SOUTHEAST ASIA: AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF CHINA, INDONESIA, AND THAILAND DR. MARK D. KIELSGARD* AND TAM HEY JUAN JULIAN** ABSTRACT This Article argues that counter-terrorism policies and formal law in many states in the East and Southeast Asian region are feeding the cur- rent spike in terror activity rather than reducing it. Regional govern- ment’s unrelated policy objectives and failure to implement or comply with norms conducive to fair treatment of “at risk” communities and their failure to adopt a prospective approach to countering terrorism is making the problem worse. This Article employs a comparative methodol- ogy of key states in the region, including China and its marginalization and forcible assimilation of minority Uighur populations; Indonesia and its radicalized majority population under a sympathetic or tolerant leadership; and Thailand, a country locked in internal strife with domestic elements seeking self-determination. It will first discuss contem- porary models of counter-terrorism, then detail relevant measures adopted in the subject states followed by an analysis concluding that, though differing in specific initiatives, these states share a functional commonal- ity motivated by objectives unrelated to counter-terrorism leading to a resultant commonality of increased terror activity. Moreover, these argu- ments are equally relevant to other countries in the region such as the Philippines and Malaysia. INTRODUCTION Terrorism is a real threat in the East and Southeast Asian region (the Region). After the 9/11 attacks in the United States, it was * Dr. -

Deconstructing the Coverage of the Syrian Conflict in Western Media

UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCES GRADUATE ACADEMIC STUDIES Regional Master’s Program in Peace Studies MASTER THESIS Deconstructing the Coverage of the Syrian Conflict in Western Media Case Study: The Economist ACADEMIC SUPERVISOR: STUDENT: Prof. dr Radmila Nakarada Uroš Mamić Enrollment No. 22/2015 Belgrade, 2018 1 DECLARATION OF ACADEMIC INTEGRITY I hereby declare that the study presented is based on my own research and no other sources than the ones indicated. All thoughts taken directly or indirectly from other sources are properly denoted as such. Belgrade, 31 August 2018 Uroš Mamić (Signature) 2 Content 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………..3 1.1. Statement of Problem ……………………………………………………………………… 3 1.2. Research Topic ………………………………………….........……………………..............4 1.3. Research Goals and Objectives ………………………………….………………….............6 1.4. Hypotheses ………………………………………………………..…………………………7 1.4.1. General Hypothesis ………………………………………………..………………………...7 1.4.2. Specific Hypotheses …………………………………………………………………………7 1.5. Research Methodology ………………………………………………………………….......8 1.6. Research Structure – Chapter Outline ……………………………………………………...10 2. Major Themes of the Syrian Conflict in The Economist ……………………………….12 2.1. Roots of the Conflict ……………………………………………………………………….13 2.2. Beginning of the Conflict – Protests and Early Armed Insurgency …………….................23 2.3. Local Actors …………………………………………………………………………….......36 2.3.1. Syrian Government Forces …………………………………………………………………37 2.3.2. Syrian Opposition ……………………………………………………………………….......41 -

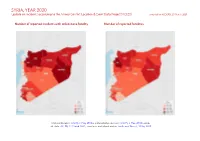

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

The Syrian Arab Republic Was Established As a French-Controlled Mandate at the End of World War I and Became Officially Independent in 1946

COUNTRIES AT THE CROSSROADS COUNTRIES AT THE CROSSROADS 2011: SYRIA 1 RADWAN ZIADEH INTRODUCTION The Syrian Arab Republic was established as a French-controlled mandate at the end of World War I and became officially independent in 1946. After a period of intermittently-democratic rule and a short merger with Egypt from 1958 to 1961, the Arab Socialist Baath Party staged a coup in 1963, established a one-party government, and declared a state of emergency that remained in place for 48 years. A period of leadership transition among civilian ideologues and army officers, most of them members of the Alawite minority (adherents of an Islamic sect who comprise approximately 12 percent of the population) continued until 1970, when Alawite and Baath Party member General Hafez al-Assad assumed the presidency. The ongoing state of emergency, Alawite dominance of the security forces, and the omnipresence of the Baath Party enabled Hafez al-Assad to maintain strict authoritarian control over virtually all sectors of political and social life. The regime centralized the state‟s legislative, judicial, and executive institutions under its control, restricted virtually all forms of dissent, and prohibited the operation of all independent media. The new presidential system revolved around al-Assad‟s personal will and networks of social, economic, and military interests based on personal loyalty to the president. Syria‟s 1973 constitution designates the Baath as “the leader party in the state and society,” and the state is its sole source of funds, creating a very close relationship that renders indistinguishable the distinction between government institutions and ruling party. -

No. 2 Newsmaker of 2016 Was City Manager Change Rodgers Christmas Basket Fund Are Still Being Accepted

FRIDAY 162nd YEAR • No. 208 DECEMBER 30, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 22 PAGES • 50¢ Basket Fund Donations to the William Hall No. 2 Newsmaker of 2016 was city manager change Rodgers Christmas Basket Fund are still being accepted. Each By LARRY C. BOWERS Service informed Council members of year, the fund supplies boxes of Banner Staff Writer the search process they faced. food staples to needy families TOP 10 MTAS provided assistance free of during the holiday season. The The Cleveland City Council started charge, and Norris recommended the fund, which is a 501(c)(3) charity, the 2016 calendar year with a huge city hire a consultant. This was prior is a volunteer-suppported effort. challenge — an ordeal which devel- NEWSMAKERS to the Council’s decision to hire Any funds over what is needed to oped into the No. 2 news story of the Wallace, who had also assisted with pay for food bought this year will year as voted by Cleveland Daily the city’s hiring of Police Chief Mark be used next Christmas. Banner staff writers and editors — The huge field of applicants was Gibson. Donations may be mailed to First when the city celebrated the retire- vetted by city consultant and former Council explored the possibility of Tennessee Bank, P.O. Box 3566, ment of City Manager Janice Casteel Tennessee Bureau of Investigation using MTAS and a recruiting agency, Cleveland TN 37320-3566 or and announced the hiring of new City Director Larry Wallace, of Athens, as but Norris told them she had never dropped off at First Tennessee Manager Joe Fivas. -

132484385.Pdf

MAANPUOLUSTUSKORKEAKOULU VENÄJÄN OPERAATIO SYYRIASSA – TARKASTELU VENÄJÄN ILMAVOIMIEN KYVYSTÄ TUKEA MAAOPERAATIOTA Diplomityö Kapteeni Valtteri Riehunkangas Yleisesikuntaupseerikurssi 58 Maasotalinja Heinäkuu 2017 MAANPUOLUSTUSKORKEAKOULU Kurssi Linja Yleisesikuntaupseerikurssi 58 Maasotalinja Tekijä Kapteeni Valtteri Riehunkangas Tutkielman nimi VENÄJÄN OPERAATIO SYYRIASSA – TARKASTELU VENÄJÄN ILMAVOI- MIEN KYVYSTÄ TUKEA MAAOPERAATIOTA Oppiaine johon työ liittyy Säilytyspaikka Operaatiotaito ja taktiikka MPKK:n kurssikirjasto Aika Heinäkuu 2017 Tekstisivuja 137 Liitesivuja 132 TIIVISTELMÄ Venäjä suoritti lokakuussa 2015 sotilaallisen intervention Syyriaan. Venäjä tukee Presi- dentti Bašar al-Assadin hallintoa taistelussa kapinallisia ja Isisiä vastaan. Vuoden 2008 Georgian sodan jälkeen Venäjän asevoimissa aloitettiin reformi sen suorituskyvyn paran- tamiseksi. Syyrian intervention aikaan useat näistä uusista suorituskyvyistä ovat käytössä. Tutkimuksen tavoitteena oli selvittää Venäjän ilmavoimien kyky tukea maaoperaatiota. Tutkimus toteutettiin tapaustutkimuksena. Tapauksina työssä olivat kolme Syyrian halli- tuksen toteuttamaa operaatiota, joita Venäjä suorituskyvyillään tuki. Venäjän interventiosta ei ollut saatavilla opinnäytetöitä tai kirjallisuutta. Tästä johtuen tutkimuksessa käytettiin lähdemateriaalina sosiaaliseen mediaan tuotettua aineistoa sekä uutisartikkeleita. Koska sosiaalisen median käyttäjien luotettavuutta oli vaikea arvioida, tutkimuksessa käytettiin videoiden ja kuvien geopaikannusta (geolocation, geolokaatio), joka -

Eroticism in the Works of Contemporary Egyptian and Levantine Female Novelists Ibtihal R Mahmood a Thesis Submitted in Partial F

Eroticism in the Works of Contemporary Egyptian and Levantine Female Novelists Ibtihal R Mahmood A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Middle East University of Washington 2018 Committee: Terri DeYoung Selim Kuru Program authorized to offer degree: The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies 1 ©Copyright 2018 Ibtihal R Mahmood 2 University of Washington Abstract Eroticism in the Works of Contemporary Egyptian and Levantine Female Novelists Ibtihal R Mahmood Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Terri DeYoung Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization Literary and narrative discourses hold an inherent correspondence between themselves and the social, economic, national, and political issues that govern the atmosphere in which they emerge, including those concerning the war of the classes and of the sexes. Using the erotic as a parameter, this paper analyzes three novels by three contemporary women novelists from Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria: Nawāl el-Sa’dāwī, Ḥanān al-Shaykh, and Samar Yazbek, respectively. An analysis of the combination of language, culture, and space can lend itself to an examination of the relationships of power and social hierarchies that govern societies, in a fashion that follows the Foucauldian power/knowledge social theory. Adopting the Lacanian perspective of language as an inherently sexist utility, this paper examines the approaches found in these three novels to the objectification of the female body; the yearning to reclaim agency; and the success – and failure – in regaining and retaining autonomy. 3 Contents Chapter One Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter Two Desire, Abjection, and Social Hierarchy Nawāl el-Sa’dāwī – Egypt ................................ -

Kata'ib Sayyid Al Shuhada

Kata’ib Sayyid al Shuhada Name: Kata’ib Sayyid al Shuhada Type of Organization: Militia political party religious social services provider terrorist transnational violent Ideologies and Affiliations: Iranian-sponsored Shiite Jihadist Khomeinist Place of Origin: Iraq Year of Origin: 2013 Founder(s): Abu Mustafa al Sheibani Places of Operation: Iraq, Syria Overview Also Known As Kata’ib Abu Fadl al-Abbas1 Kata’ib Karbala2 Battalion of the Sayyid’s Martyrs3 Executive Summary Kata’ib Sayyid al Shuhada (KSS) is an Iraqi militia that has fought in both Iraq and Syria and is closely connected to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Houthis.4 Its leader is Abu Mustafa al Sheibani, a U.S.-designated terrorist who also assisted in forming the IRGC-backed Asaib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) and Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH) militias.5 The group was founded in 2013. Its first public announcements were three martyrdom notices for members killed fighting in southern Damascus alongside Syrian regime forces.6 In Syria, KSS operates within the fold of the mixed Syrian and Iraqi Liwa Abu Fadl al-Abbas, another Iranian- backed militia.7 KSS follows the same Shiite jihadist ideology as fellow pro-Iranian Iraqi militias, framing its fight in Syria as a defense of Shiites and the Shiite shrine of Sayyida Zaynab.8 In a 2013 interview, KSS’s information office stated that the group sent 500 militants to Syria.9 Other media Kata’ib Sayyid al Shuhada statements have affirmed the presence of KSS fighters in rural Damascus along the frontlines in eastern Ghouta.10 The Associated Press has reported that KSS fighters enter Syria via Iran.11 In 2015, KSS declared Saudi Arabia “a legitimate and permissible target” after that country executed a prominent Shiite cleric.12 A 2018 KSS statement indicated the group was ready to send fighters to Yemen. -

The Interest of States in Accountability for Sexual Violence in Armed

Military Self-Interest in Accountability for Core International Crimes Morten Bergsmo and SONG Tianying (editors) PURL: http://www.legal-tools.org/doc/08dd00/ E-Offprint: Kiki Anastasia Japutra, “The Interest of States in Accountability for Sexual Violence in Armed Conflicts: A Case Study of Comfort Women of the Second World War”, in Morten Bergsmo and SONG Tianying (editors), Military Self-Interest in Accountability for Core International Crimes, FICHL Publication Series No. 25 (2015), Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, Brussels, ISBN 978-82-93081-81-4. First published on 29 May 2015. This publication and other TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the website www.fichl.org. This site uses Persistent URLs (PURL) for all publications it makes available. The URLs of these publications will not be changed. Printed copies may be ordered through online distributors such as www.amazon.co.uk. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2015. All rights are reserved. PURL: http://www.legal-tools.org/doc/08dd00/ 10 ______ The Interest of States in Accountability for Sexual Violence in Armed Conflicts: A Case Study of Comfort Women of the Second World War Kiki Anastasia Japutra* The term ‘comfort women’ or ianfu (also jugun ianfu or military comfort women) refers to hundreds of thousands of women recruited to serve the Japanese military as sex workers during the Second World War.1 An es- timated 80 per cent were Koreans while the rest comprised women from China, Southeast Asia, Taiwan and the Pacific region. To facilitate this practice, military installations known as so-called comfort stations were established all over Asia, in territories where Japanese troops were de- ployed. -

From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’S Popular Mobilisation Units

From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units By Inna Rudolf CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 20 7848 2098 E. [email protected] Twitter: @icsr_centre Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2018 From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units Contents List of Key Terms and Actors 2 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 – The Birth and Institutionalisation of the PMU 11 Chapter 2 – Organisational Structure and Leading Formations of Key PMU Affiliates 15 The Usual Suspects 17 Badr and its Multi-vector Policy 17 The Taming of the “Special Groups” 18 Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq – Righteousness with Benefits? 18 Kata’ib Hezbollah and the Iranian Connection 19 Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada – Seeking Martyrdom in Syria? 20 Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba – a Hezbollah Wannabe? 21 Saraya al-Khorasani – Tehran’s Satellite in Iraq? 22 Kata’ib Tayyar al-Risali – Iraqi Loyalists with Sadrist Roots 23 Saraya al-Salam – How Rebellious are the Peace Brigades? 24 Hashd al-Marji‘i – the ‘Holy’ Mobilisation 24 Chapter 3 – Election Manoeuvring 27 Betting on the Hashd 29 Chapter 4 – Conclusion 33 1 From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units List of Key Terms and Actors AAH: -

ISLAMIC-MONUMENTS.Pdf

1 The Masjid-i Jami of Herat, the city's first congregational mosque, was built on the site of two smaller Zoroastrian fire temples that were destroyed by earthquake and fire. A mosque construction was started by the Ghurid ruler Ghiyas ad-Din Ghori in 1200 (597 AH), and, after his death, the building was continued by his brother and successor Muhammad of Ghor. In 1221, Genghis Khan conquered the province, and along with much of Herat, the small building fell into ruin. It wasn't until after 1245, under Shams al-Din Kart that any rebuilding programs were undertaken, and construction on the mosque was not started until 1306. However, a devastating earthquake in 1364 left the building almost completely destroyed, although some attempt was made to rebuild it. After 1397, the Timurid rulers redirected Herat's growth towards the northern part of the city. This suburbanization and the building of a new congregational mosque in Gawhar Shad's Musalla marked the end of the Masjid Jami's patronage by a monarchy. 2 This mosque was constructed in 1888 and was the first mosque in any Australian capital city. It has four minarets which were built in 1903 for 150 pounds by local cameleers with some help from Islamic sponsors from Melbourne. Its founding members lie in the quiet part of the South West corner of the city. 3 The Cyprus Turkish Islamic Community of Victoria was established in Richmond, Clifton Hill, and was then relocated to Ballarat Road, Sunshine in 1985 The Sunshine Mosque is the biggest Mosque in Victoria, and has extended its services to cater for ladies, elderly and youth groups.