Remembering Beirut: Lessons for Archaeology and (Post-) Conflict Urban Redevelopment in Aleppo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beirut Residents' Perspectives on August 4

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SEPTEMBER 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized BEIRUT RESIDENTS’ PERSPECTIVES ON AUGUST 4 BLAST Findings from a needs and perception survey © 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of the World Bank with external contributions. The findings, Beirut interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the Residents’ World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. Needs and Perception The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, Survey colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because the World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522- 2625; e-mail: [email protected]. 2 Disclaimer The survey collected information related to five main themes: socio-economic status, damage assessment, trust in institutions, future outlook, and needs and concerns. -

Sidon's Ancient Harbour

ARCHAEOLOGY & H ISTORY SIDON’S ANCIENT HARBOUR: IN THE LEBANON ISSUE THIRTY FOUR -T HIRTY FIVE : NATURAL CHARACTERISTICS WINTER /S PRING 2011/12. AND HAZARDS PP. 433-459. N. CARAYON 1 C. MORHANGE 2 N. MARRINER 2 1 CNRS UMR 5140, A multidisciplinary study combining geoscience, archaeology and his - Lattes ([email protected]) tory was conducted on Sidon’s harbour (Lebanon). The natural charac - teristics of the site at the time of the harbour’s foundation were deter - 2 CNRS CEREGE UMR mined, as well as the human resources that were needed to improve 6635, Aix-Marseille Université, Aix-en- these conditions in relation to changes in maritime activity. In ancient Provence times, Sidon was one of the most active harbours and urban centres on ([email protected] ; the Levantine coast 3. It is therefore a key site to study ancient harbours, [email protected]). providing insight into both ancient cultures and the technological 1 Sidon’s coastal ba- thymetry. 1 apogee of the Roman and Byzantine periods. This article proposes a synthesis of Sidon’s harbour system based on geomorphological characteristics that favoured the development of a wide range of maritime facilities, refashioned and improved by human societies from the second millennium BC until the Middle Ages. 434 2 2 Aerial view of Sidon Sidon’ s coastline (fig. 1 -2) and Ziré during the 1940s (from A. Poide- The ancient urban center was developed on a rocky promontory dom - bard and J. Lauffray, inating a 2 km wide coastal plain, flanked by the Nahr el-Awali river to 1951). -

BEIRUT Responsibility of the Authors and Can in No Way Be Taken to Reflect the Views of the EU Or SDC

Co-funded by the European Union Co-funded by International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) and United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN - HABITAT). MEDITERRANEAN CITY - TO - CITY MIGRATION www.icmpd.org/MC2CM All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission of the copyright owners. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the CITY MIGRATION PROFILE European Union (EU) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Implemented by Cooperation (SDC). The content of this publication is the sole BEIRUT responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the EU or SDC. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VIENNA LYON TURIN MADRID LISBON TUNIS BEIRUT TANGIER AMMAN MIGRATION PATTERNS This document is a synthesis of the Municipality of Beirut Migration Profile and Since the second half of the 19th century most of Lebanon’s economic and cultural Priority Paper drafted in the framework of the Mediterranean City - to - City Migration activities have taken place in Beirut. The city currently boasts the country’s main Project (MC2CM). The project aims at contributing to improved migration govern- port, its only international airport, houses the government offices, and is the main ance at city level in a network of cities in Europe and the Southern Mediterranean cultural and educational centre. Beirut has therefore attracted various waves of region. More information is available at www.icmpd.org/MC2CM. -

Deconstructing the Coverage of the Syrian Conflict in Western Media

UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCES GRADUATE ACADEMIC STUDIES Regional Master’s Program in Peace Studies MASTER THESIS Deconstructing the Coverage of the Syrian Conflict in Western Media Case Study: The Economist ACADEMIC SUPERVISOR: STUDENT: Prof. dr Radmila Nakarada Uroš Mamić Enrollment No. 22/2015 Belgrade, 2018 1 DECLARATION OF ACADEMIC INTEGRITY I hereby declare that the study presented is based on my own research and no other sources than the ones indicated. All thoughts taken directly or indirectly from other sources are properly denoted as such. Belgrade, 31 August 2018 Uroš Mamić (Signature) 2 Content 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………..3 1.1. Statement of Problem ……………………………………………………………………… 3 1.2. Research Topic ………………………………………….........……………………..............4 1.3. Research Goals and Objectives ………………………………….………………….............6 1.4. Hypotheses ………………………………………………………..…………………………7 1.4.1. General Hypothesis ………………………………………………..………………………...7 1.4.2. Specific Hypotheses …………………………………………………………………………7 1.5. Research Methodology ………………………………………………………………….......8 1.6. Research Structure – Chapter Outline ……………………………………………………...10 2. Major Themes of the Syrian Conflict in The Economist ……………………………….12 2.1. Roots of the Conflict ……………………………………………………………………….13 2.2. Beginning of the Conflict – Protests and Early Armed Insurgency …………….................23 2.3. Local Actors …………………………………………………………………………….......36 2.3.1. Syrian Government Forces …………………………………………………………………37 2.3.2. Syrian Opposition ……………………………………………………………………….......41 -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

No. 2 Newsmaker of 2016 Was City Manager Change Rodgers Christmas Basket Fund Are Still Being Accepted

FRIDAY 162nd YEAR • No. 208 DECEMBER 30, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 22 PAGES • 50¢ Basket Fund Donations to the William Hall No. 2 Newsmaker of 2016 was city manager change Rodgers Christmas Basket Fund are still being accepted. Each By LARRY C. BOWERS Service informed Council members of year, the fund supplies boxes of Banner Staff Writer the search process they faced. food staples to needy families TOP 10 MTAS provided assistance free of during the holiday season. The The Cleveland City Council started charge, and Norris recommended the fund, which is a 501(c)(3) charity, the 2016 calendar year with a huge city hire a consultant. This was prior is a volunteer-suppported effort. challenge — an ordeal which devel- NEWSMAKERS to the Council’s decision to hire Any funds over what is needed to oped into the No. 2 news story of the Wallace, who had also assisted with pay for food bought this year will year as voted by Cleveland Daily the city’s hiring of Police Chief Mark be used next Christmas. Banner staff writers and editors — The huge field of applicants was Gibson. Donations may be mailed to First when the city celebrated the retire- vetted by city consultant and former Council explored the possibility of Tennessee Bank, P.O. Box 3566, ment of City Manager Janice Casteel Tennessee Bureau of Investigation using MTAS and a recruiting agency, Cleveland TN 37320-3566 or and announced the hiring of new City Director Larry Wallace, of Athens, as but Norris told them she had never dropped off at First Tennessee Manager Joe Fivas. -

Bekaa & Baalbek

Lebanon September 2018 Bekaa & Baalbek - El-Hermel Governorates Prole POPULATION OVERVIEW 926,915 GENERAL OVERVIEW The Bekaa valley region is People living in Bekaa and administratively split into two Baalbek - El-Hermel Governorates governorates: Baalbek/Hermel Akkar Al Qaa (located in the north) and Bekaa Hermel 555,149 (located in the south). Along Lebanese the Bekaa region lies Lebanon’s North 59% largest ocial border crossing Baalbek/Aarsal with Syria, located in the Baalbek/El-Hermel Hermel 174,763 Masnaa locality. The region is Mount Baalbek P Deprived Beirut Lebanon home to 555,149 Lebanese, Wavel Lebanese 23,7 per cent of which are Zahle considered deprived, in Bekaa Refugees Masnaa 38% addition to 338,577 registered Joub Janine Syrian refugees, 16,863 Governorate boundaries Rachaiya Palestinians and 16,326 Capital Lebanese returnees, as the Major Towns West Bekaa Baalbek El -Hermel Rachaiya Zahle region makes up the vast El Nabatieh P Palestinian Camps majority of Lebanon’s 375 km South Official border crossing status border with Syria. With more 43% Open 32% than half of its population Closed Lebanese being refugees, the region is one of the most aected by the Unofficial Syrian crisis. crossing Registered Syrian 45% Refugees 33% Until August 2017, Baalbek’s north-eastern border was the site of sporadic armed clashes opposing Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) and Hezbollah to Islamist Armed 338,577 Opposition Groups (I/AOG) around the localities of Aarsal, al-Zoueitini, Khreibeh, Qaa and Ras Baalbek. Some border towns were also subject to suicide bombings Palestine Refugees and Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). -

Chronos Uses the Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-SA That Lets You Remix, Transform, and Build Upon the Material for Non-Commercial Purposes

Chronos- Revue d’Histoire de l’Université de Balamand, is a bi-annual Journal published in three languages (Arabic, English and French). It deals particularly with the History of the ethnic and religious groups of the Arab world. Journal Name: Chronos ISSN: 1608-7526 Title: Archaeology of Medieval Lebanon: an Overview Author(s): Tasha Voderstrasse To cite this document: Voderstrasse, T. (2019). Archaeology of Medieval Lebanon: an Overview. Chronos, 20, 103-128. https://doi.org/10.31377/chr.v20i0.476 Permanent link to this document: DOI: https://doi.org/10.31377/chr.v20i0.476 Chronos uses the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA that lets you remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes. However, any derivative work must be licensed under the same license as the original. CHl{ONOS Revue d'Histoirc de l'Univcrsite de Balamand Numero 20, 2009, ISSN 1608 7526 ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEDIEVAL LEBANON: AN OVERVIEW T ASHA VORDERSTRASSE 1 Introduction This article will present an overview of the archaeological work done on medieval Lebanon from the 19th century to the present. The period under examination is the late medieval period, from the 11th to the 14th centuries, encompassing the time when the region was under the control of various Islamic dynasties and the Crusaders. The archaeology of Le banon has been somewhat neglected over the years, despite its importance for our understanding of the region in the medieval period, mainly because of the civil war (1975-1990), which made excavations and surveys in the country impossible and led to the widespread looting of sites (Hakiman 1987; Seeden 1987; Seeden 1989; Fisk 1991 ; Hakiman 1991; Ward 1995; Hackmann 1998; Sader 2001. -

The Archaeology of Conflict-Damaged Sites: Hosn Niha in the Biqaʾ

The archaeology of conflict-damaged sites: Hosn Niha in the Biqaʾ Valley, Lebanon Paul Newson1 &RuthYoung2 Archaeological and cultural heritage is always at risk of damage and destruction in areas of conflict. Despite legislation to protect sites and minimise the impact of war or civil unrest, much archaeological data is still being lost, not least in the Middle East. Careful Hosn Niha research design and methodological recording Beirut strategies tailored to sites destroyed by conflict or looting can, however, provide much more Method information than previously imagined. This is illustrated by a case study focusing on the Roman settlement and temples at Hosn N Niha in the Biqaʾ Valley, which were 0 km 50 severely damaged in the 1980s during the Lebanese Civil War. Sufficient information was recovered to reconstruct many details, including the chronology and development of the site. Keywords: Lebanon, Roman settlement, conflict archaeology, looting, Cultural Resource Management, GIS Introduction When faced with the destruction of archaeological sites through conflict and the accompanying loss of knowledge, what can archaeologists do? In this paper, we use the example of a site in Lebanon, which has been severely damaged by multiple conflict episodes, to show that a great deal can be learned from an apparently destroyed site by careful fieldwork and analysis. Conflict is arguably an integral part of human interaction, and archaeological studies have provided evidence for conflict from as early as the Palaeolithic (Thorpe 2003). Conflicts have occurred throughout prehistory and history, and they are an inescapable evil in many parts of the world today (Boylan 2002). The human cost in any conflict is high and, obviously, protecting people has to be the first priority during such periods. -

ISLAMIC-MONUMENTS.Pdf

1 The Masjid-i Jami of Herat, the city's first congregational mosque, was built on the site of two smaller Zoroastrian fire temples that were destroyed by earthquake and fire. A mosque construction was started by the Ghurid ruler Ghiyas ad-Din Ghori in 1200 (597 AH), and, after his death, the building was continued by his brother and successor Muhammad of Ghor. In 1221, Genghis Khan conquered the province, and along with much of Herat, the small building fell into ruin. It wasn't until after 1245, under Shams al-Din Kart that any rebuilding programs were undertaken, and construction on the mosque was not started until 1306. However, a devastating earthquake in 1364 left the building almost completely destroyed, although some attempt was made to rebuild it. After 1397, the Timurid rulers redirected Herat's growth towards the northern part of the city. This suburbanization and the building of a new congregational mosque in Gawhar Shad's Musalla marked the end of the Masjid Jami's patronage by a monarchy. 2 This mosque was constructed in 1888 and was the first mosque in any Australian capital city. It has four minarets which were built in 1903 for 150 pounds by local cameleers with some help from Islamic sponsors from Melbourne. Its founding members lie in the quiet part of the South West corner of the city. 3 The Cyprus Turkish Islamic Community of Victoria was established in Richmond, Clifton Hill, and was then relocated to Ballarat Road, Sunshine in 1985 The Sunshine Mosque is the biggest Mosque in Victoria, and has extended its services to cater for ladies, elderly and youth groups. -

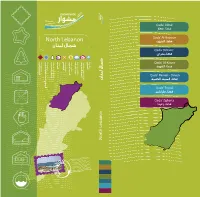

Layout CAZA AAKAR.Indd

Qada’ Akkar North Lebanon Qada’ Al-Batroun Qada’ Bcharre Monuments Recreation Hotels Restaurants Handicrafts Bed & Breakfast Furnished Apartments Natural Attractions Beaches Qada’ Al-Koura Qada’ Minieh - Dinieh Qada’ Tripoli Qada’ Zgharta North Lebanon Table of Contents äÉjƒàëªdG Qada’ Akkar 1 QɵY AÉ°†b Map 2 á£jôîdG A’aidamoun 4-27 ¿ƒeó«Y Al-Bireh 5-27 √ô«ÑdG Al-Sahleh 6-27 á∏¡°ùdG A’andaqet 7-28 â≤æY A’arqa 8-28 ÉbôY Danbo 9-29 ƒÑfO Deir Jenine 10-29 ø«æL ôjO Fnaideq 11-29 ¥ó«æa Haizouq 12-30 ¥hõ«M Kfarnoun 13-30 ¿ƒfôØc Mounjez 14-31 õéæe Qounia 15-31 É«æb Akroum 15-32 ΩhôcCG Al-Daghli 16-32 »∏ZódG Sheikh Znad 17-33 OÉfR ï«°T Al-Qoubayat 18-33 äÉ«Ñ≤dG Qlaya’at 19-34 äÉ©«∏b Berqayel 20-34 πjÉbôH Halba 21-35 ÉÑ∏M Rahbeh 22-35 ¬ÑMQ Zouk Hadara 23-36 √QGóM ¥hR Sheikh Taba 24-36 ÉHÉW ï«°T Akkar Al-A’atiqa 25-37 á≤«à©dG QɵY Minyara 26-37 √QÉ«æe Qada’ Al-Batroun 69 ¿hôàÑdG AÉ°†b Map 40 á£jôîdG Kouba 42-66 ÉHƒc Bajdarfel 43-66 πaQóéH Wajh Al-Hajar 44-67 ôéëdG ¬Lh Hamat 45-67 äÉeÉM Bcha’aleh 56-68 ¬∏©°ûH Kour (or Kour Al-Jundi) 47-69 (…óæédG Qƒc hCG) Qƒc Sghar 48-69 Qɨ°U Mar Mama 49-70 ÉeÉe QÉe Racha 50-70 É°TGQ Kfifan 51-70 ¿ÉØ«Øc Jran 52-71 ¿GôL Ram 53-72 ΩGQ Smar Jbeil 54-72 π«ÑL Qɪ°S Rachana 55-73 ÉfÉ°TGQ Kfar Helda 56-74 Gó∏MôØc Kfour Al-Arabi 57-74 »Hô©dG QƒØc Hardine 58-75 øjOôM Ras Nhash 59-75 ¢TÉëf ¢SGQ Al-Batroun 60-76 ¿hôàÑdG Tannourine 62-78 øjQƒæJ Douma 64-77 ÉehO Assia 65-79 É«°UCG Qada’ Bcharre 81 …ô°ûH AÉ°†b Map 82 á£jôîdG Beqa’a Kafra 84-97 GôØc ´É≤H Hasroun 85-98 ¿hô°üM Bcharre 86-97 …ô°ûH Al-Diman 88-99 ¿ÉªjódG Hadath -

Syria: Playing Into Their Hands

Syria Playing into their hands Regime and international roles in fuelling violence and fundamentalism in the Syrian war DAVID KEEN Syria Playing into their hands Regime and international roles in fuelling violence and fundamentalism in the Syrian war DAVID KEEN About the author David Keen is a political economist and Professor of Conflict Studies at the London School of Economics (LSE), where he has worked since 1997. He is the author of several books on conflict and related problems, includingUseful Enemies, Complex Emergencies, Endless War? and The Benefits of Famine. Saferworld published a discussion paper by Professor Keen in 2015 entitled Dilemmas of counter-terror, stabilisation and statebuilding, on which this paper builds. Acknowledgements This discussion paper was commissioned as part of Saferworld’s work to challenge counterproductive responses to crises and critical threats and promote peacebuilding options. It has been managed and edited by Larry Attree and Jordan Street for Saferworld. Very valuable comments and advice, on all or parts of the text, were additionally provided by Rana Khalaf, Henry Smith, Fawaz Gerges, Rajesh Venugopal, Stuart Gordon, Paul Kingston, Sune Haugbolle, Leonie Northedge, Shelagh Daley and David Alpher. Any errors are solely the responsibility of the author. The author is grateful to Mary Kaldor at LSE for supporting the fieldwork component of this research, funded by the European Research Council. I am particularly grateful to Ali Ali for his guidance and inside knowledge during fieldwork on the Turkey-Syria border and for subsequent comments. Some people have helped greatly with this report who cannot be individually acknowledged for security reasons and my sincere gratitude extends to them.