Marina Vinnik University of Leipzig an Attempt of Feminist Art Historiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Institute of Modern Russian Culture

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 61, February, 2011 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089‐4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740‐2735 or (213) 743‐2531 Fax: (213) 740‐8550; E: [email protected] website: hƩp://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the sixty-first biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in August, 2010. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the fall and winter of 2010. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2010 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 for overseas airmail). RUSSIA If some observers are perturbed by the ostensible westernization of contemporary Russia and the threat to the distinctiveness of her nationhood, they should look beyond the fitnes-klub and the shopping-tsentr – to the persistent absurdities and paradoxes still deeply characteristic of Russian culture. In Moscow, for example, paradoxes and enigmas abound – to the bewilderment of the Western tourist and to the gratification of the Russianist, all of whom may ask why – 1. the Leningradskoe Highway goes to St. Petersburg; 2. the metro stop for the Russian State Library is still called Lenin Library Station; 3. there are two different stations called “Arbatskaia” on two different metro lines and two different stations called “Smolenskaia” on two different metro lines; 4. -

The Institute of Modern Russian Culture

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 62, August, 2011 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089‐4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740‐2735 Fax: (213) 740‐8550; E: [email protected] website: hp://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the sixty-second biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in February, 2011. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the spring and summer of 2011. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2010 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 for overseas airmail). RUSSIA To those who remember the USSR, the Soviet Union was an empire of emptiness. Common words and expressions were “defitsit” [deficit], “dostat’”, [get hold of], “seraia zhizn’” [grey life], “pusto” [empty], “magazin zakryt na uchet” [store closed for accounting] or “na pereuchet” [for a second accounting] or “na remont” (for repairs)_ or simply “zakryt”[closed]. There were no malls, no traffic, no household trash, no money, no consumer stores or advertisements, no foreign newspapers, no freedoms, often no ball-point pens or toilet-paper, and if something like bananas from Cuba suddenly appeared in the wasteland, they vanished within minutes. -

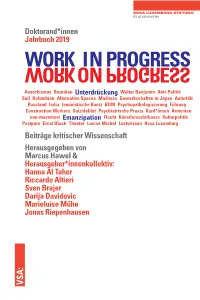

Workonprogress Work in Progress On

STUDIENWERK Doktorand*innen Jahrbuch 2019 ORK ON PROGRESS WORK INPROGRESS ON Anarchismus Bourdieu Unterdrückung Walter Benjamin Anti-Politik Exil Kolumbien Alternative Spaces Madness Gewerkschaften in Japan Autorität Russland India feministische Kunst BDM Psychopathologisierung Führung Construction Workers Suizidalität Psychiatrische Praxis Kurd*innen Armenien non-movement Emanzipation Flucht Künstlersozialkasse Kulturpolitik Postporn Ernst Bloch Theater Louise Michel Lustwissen Rosa Luxemburg Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel & Herausgeber*innenkollektiv: Hanna Al Taher Riccardo Altieri Sven Brajer Darija Davidovic Marieluise Mühe Jonas Riepenhausen VSA: WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS Doktorand*innen-Jahrbuch 2019 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS. Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Doktorand*innenjahrbuch 2019 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel Herausgeber*innenkollektiv: Hanna Al Taher, Riccardo Altieri, Sven Brajer, Darija Davidovic, Marieluise Mühe und Jonas Riepenhausen VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de/studienwerk Die Doktorand*innenjahrbücher 2012 (ISBN 978-3-89965-548-3), 2013 (ISBN 978-3-89965-583-4), 2014 (ISBN 978-3-89965-628-2), 2015 (ISBN 978-3-89965-684-8), 2016 (ISBN 978-3-89965-738-8) 2017 (ISBN 978-3-89965-788-3), 2018 (ISBN 978-3-89965-890-3) der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung sind ebenfalls im VSA: Verlag erschienen und können unter www.rosalux.de als pdf-Datei heruntergeladen werden. Dieses Buch wird unter den Bedingungen einer Creative Com- mons License veröffentlicht: Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License (abrufbar un- ter www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode). Nach dieser Lizenz dürfen Sie die Texte für nichtkommerzielle Zwecke vervielfältigen, ver- breiten und öffentlich zugänglich machen unter der Bedingung, dass die Namen der Autoren und der Buchtitel inkl. -

Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/98 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Wendy Rosslyn is Emeritus Professor of Russian Literature at the University of Nottingham, UK. Her research on Russian women includes Anna Bunina (1774-1829) and the Origins of Women’s Poetry in Russia (1997), Feats of Agreeable Usefulness: Translations by Russian Women Writers 1763- 1825 (2000) and Deeds not Words: The Origins of Female Philantropy in the Russian Empire (2007). Alessandra Tosi is a Fellow at Clare Hall, Cambridge. Her publications include Waiting for Pushkin: Russian Fiction in the Reign of Alexander I (1801-1825) (2006), A. M. Belozel’skii-Belozerskii i ego filosofskoe nasledie (with T. V. Artem’eva et al.) and Women in Russian Culture and Society, 1700-1825 (2007), edited with Wendy Rosslyn. Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture Edited by Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi Open Book Publishers CIC Ltd., 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2012 Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial -

The 12 Days of Christmas

MOSCOW DECEMBER 2010 www.passportmagazine.ru THE 12 DAYS OF CHRISTMAS Why Am I Here? The Master of Malaya Bronnaya The 1991 Coup from atop the White House Sheffi eld Joins the Space Race Christmas Tipples The English word for фарт December_covers.indd 1 22.11.2010 14:16:04 December_covers.indd 2 22.11.2010 14:57:06 Contents 3. Editor’s Choice Alevitina Kalinina and Olga Slobodkina 8. Clubs Get ready Moscow, nightlife’s evolving! Max Karren- berg, DJs Eugene Noiz and Julia Belle, Imperia, Poch Friends, Rai Club, Imperia, Harleys and Lamborghinis, Miguel Francis 8 10. Theatre Review Play Actor & Uncle Vanya at the Tabakov Theatre. Don Juan at The Bolshoi Theatre, Our Man from Havanna at The Malaya Bronnaya Theatre, Por Una Cabeza and Salute to Sinatra at The Yauza Palace, Marina Lukanina 12. Art The 1940s-1950s, Olga Slobodkina Zinaida Serebriakova in Moscow, Ross Hunter 11 16. The Way it Was The Coup, John Harrison Inside the White House, John Harrison UK cosmonaut, Helen Sharman, Helen Womack Hungry Russians, Helen Womack 20. The Way It Is Why I Am Here part II, Franck Ebbecke 20 22. Real Estate Moscow’s Residential Architecture, Vladimir Kozlev Real Estate News, Vladimir Kozlev 26. Your Moscow The Master of Malaya Bronnaya, Katrina Marie 28. Wine & Dining New Year Wine Buyer Guide, Charles Borden 26 Christmas Tipples, Eleanora Scholes Tutto Bene (restaurant), Mandisa Baptiste Restaurant and Bar Guide Marseille (restaurant), Charles Borden Megu, Charles Borden 38. Out & About 42. My World Ordinary Heroes, Helen Womack 38 Dare to ask Deidre, Deidre Dare 44. -

Resilient Russian Women in the 1920S & 1930S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 8-19-2015 Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Russian Literature Commons, Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s" (2015). Zea E-Books. Book 31. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/31 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Marcelline Hutton Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s The stories of Russian educated women, peasants, prisoners, workers, wives, and mothers of the 1920s and 1930s show how work, marriage, family, religion, and even patriotism helped sustain them during harsh times. The Russian Revolution launched an economic and social upheaval that released peasant women from the control of traditional extended fam- ilies. It promised urban women equality and created opportunities for employment and higher education. Yet, the revolution did little to elim- inate Russian patriarchal culture, which continued to undermine wom- en’s social, sexual, economic, and political conditions. Divorce and abor- tion became more widespread, but birth control remained limited, and sexual liberation meant greater freedom for men than for women. The transformations that women needed to gain true equality were post- poned by the pov erty of the new state and the political agendas of lead- ers like Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin. -

Russian Art & History

RUSSIAN ART & HISTORY HÔTEL MÉTROPOLE MONACO 7-8 JULY 2020 FRONT COVER: LOT 217 - SOVIET PORCELAIN Propaganda Plate ‘History of the October Takeover. 1917’ ABOVE: LOT 18 - NIKOLAY ROERICH The Borodin’s opera “Prince Igor”, 1914 LOT 333 - BALMONT K.D., AUTOGRAPH Handwritten collection of poems PAR LE MINISTERE DE MAITRE CLAIRE NOTARI HUISSIER DE JUSTICE A MONACO RUSSIAN ART & HISTORY RUSSIAN ART TUESDAY JULY 7, 2020 - 14.00 FINE ART & OBJECTS OF VERTU WEDNESDAY JULY 8, 2020 - 14:00 AUTOGRAPHS, MANUSCRIPTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS WEDNESDAY JULY 8, 2020 - 17:00 Hotel Metropole - 4 avenue de la Madone - 98000 MONACO PREVIEW BY APPOINTMENT www.hermitagefineart.com Inquiries - tel: +377 97773980 - Email: [email protected] 25, Avenue de la Costa - 98000 Monaco Tel: +377 97773980 www.hermitagefineart.com Sans titre-1 1 26/09/2017 11:33:03 SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES In-house experts Hermitage Fine Art expresses its gratitude to Anna Burovа for help with descriptions of the decorative objects of art. Hermitage Fine Art would like to express its gratitude to Igor Elena Efremova Maria Lorena Anna Chouamier Evgenia Lapshina Sergey Podstanitsky Kouznetsov for his Director Franchi Deputy Director Expert Specially Invited support with IT. Deputy Director Manuscripts & Expert and Advisor rare Bookes Paintings (Moscow) Catalogue Design: Darya Spigina Photography: François Fernandez Eric Teisseire Yolanda Lopez Franck Levy Elisa Passaretti Georgy Latariya Yana Ustinova Administrator Accountant Auction assistant Expert Invited Expert Icons Russian Decorative Arts Ivan Terny Stephen Cristea Sergey Cherkashin Auctioneer Auctioneer Invited Advisor Translator and Editor (Moscow) TRANSPORTATION LIVE AUCTION WITH 8 1• AFTER GÉRARD DE LA BARTHE (1730-1810), EARLY XIX C. -

Les Echos De Phil

Les Echos de Phil. Le train-train du chef de gare. Périodique aléatoire n°7 du 1er novembre 2008. Zinaida Serebriakova (1884 – 1967). Zinaida Yevgenyevna Serebriakova est née près de Karkov en Ukraine en 1884. Elle a fait des études artistiques à Saint-Pétersbourg dans l’école de la Princesse Tenisheva. Elle a séjourné en Italie de 1902 à 1903, puis elle a travaillé dans l’atelier de Osip Braz à Saint-Pétersbourg et a passé deux ans à l’Académie de la Grande Chaumière à Paris. Récolte 1915. Autoportrait à la table d’habillage 1909. Après avoir connu une période de bonheur et de Autoportrait de Zinaida Serebriakova en 1921 et Lithographie de prospérité avant la révolution bolchevique, elle allait Zinaida Serebriakova par G. Vereiky en 1922. partager le destin tragique de nombreux de ses compatriotes. Elle perd son mari et doit élever, seule et avec très peu de ressources, ses quatre enfants. Elle s’exile en France et est séparée de deux de ses enfants qu’elle ne reverra que 36 ans plus tard ! Zinaida Serebriakova exprime au travers de ses œuvres son amour du monde et de sa beauté, particulièrement par des peintures de la campagne russe et de ses habitants. Elle excelle aussi dans la manière avec laquelle elle représente la sensualité et l’érotisme de la femme au travers de ses nombreux tableaux de nus. Nu dormant 1931. important, en limitant notamment la pullulation des chenilles et escargots. Bien que l'espèce fasse partie des coléoptères, la femelle ne peut pas voler et porte le nom de "ver". -

Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 11-2013 Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry" (2013). Zea E-Books. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/21 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry N Marcelline Hutton Many Russian women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries tried to find happy marriages, authentic religious life, liberal education, and ful- filling work as artists, doctors, teachers, and political activists. Some very remarkable ones found these things in varying degrees, while oth- ers sought unsuccessfully but no less desperately to transcend the genera- tions-old restrictions imposed by church, state, village, class, and gender. Like a Slavic “Downton Abbey,” this book tells the stories, not just of their outward lives, but of their hearts and minds, their voices and dreams, their amazing accomplishments against overwhelming odds, and their roles as feminists and avant-gardists in shaping modern Russia and, in- deed, the twentieth century in the West. -

Shapiro Auctions

Shapiro Auctions RUSSIAN AND INTERNATIONAL FINE ART & ANTIQUES Saturday - November 16, 2013 RUSSIAN AND INTERNATIONAL FINE ART & ANTIQUES 1: SPANISH 17TH C., 'Bust of Saint John the Baptist USD 5,000 - 7,000 SPANISH 17TH C., 'Bust of Saint John the Baptist Holding the Lamb of God', gilted polychrome wood, 85 x 75 x 51 cm (33 1/2 x 29 1/2 x 20 in.), 2: A RUSSIAN CALENDAR ICON, TVER SCHOOL, 16TH C., with 24 USD 20,000 - 30,000 A RUSSIAN CALENDAR ICON, TVER SCHOOL, 16TH C., with 24 various saints including several apostles, arranged in three rows. Egg tempera, gold leaf, and gesso on a wood panel with a kovcheg. The border with egg tempera and gesso on canvas on a wood panel added later. Two insert splints on the back. 47 x 34.7 cm. ( 18 1/2 x 13 3/4 in.), 3: A RUSSIAN ICON OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST, S. USHAKOV USD 7,000 - 9,000 A RUSSIAN ICON OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST, S. USHAKOV SCHOOL, LATE 17TH C., egg tempera, gold leaf and gesso on a wood panel with kovcheg. Two insert splints on the back. 54 x 44.1 cm. (21 1/4 x 17 3/8 in.), 4: A RUSSIAN ICON OF SAINT NICHOLAS THE WONDERWORKER, USD 10,000 - 15,000 A RUSSIAN ICON OF SAINT NICHOLAS THE WONDERWORKER, MOSCOW SCHOOL, 16TH C., traditionally represented as a Bishop, Nicholas blesses the onlooker with his right hand while holding an open text in his left. The two figures on either side refer to a vision before his election as a Bishop when Nicholas saw the Savior on one side of him holding the Gospels, and the Mother of God on the other one holding out the vestments he would wear as a Bishop. -

Auktionskatalog Die Objekttitel Anklicken Um Ein Ausführliches Expose Des Objektes (PDF-Format Inklusive Bilder) Von Unserem Webserver Abzurufen

Kunst- und Auktionshaus Eva Aldag 189. Kunst Auktion am 25.05.2013, Beginn 11:00 Uhr Vorbesichtung vom 21.05.2013 bis 24.05.2013 jeweils von 10 - 19 Uhr sowie 2 Stunden vor Auktionsbeginn Katalog-Nr.: 49 Lovis Corinth (1858 - 1925) - Öl auf Leinwand, "Stehender, weiblicher Halbakt" INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Gemälde 1 - 294 294 Objekte Graphik 295 - 387 93 Objekte Bronzen 397 - 416 16 Objekte Silber 422 - 642 221 Objekte Porzellan 645 - 787 142 Objekte Glas 791 - 884 94 Objekte Möbel 894 - 954 61 Objekte Spiegel 960 - 970 11 Objekte Asiatika 975 - 1007 32 Objekte Kleinkunst 1008 - 1059 47 Objekte Teppiche 1060 - 1068 9 Objekte Schmuck 1070 - 1166 97 Objekte Uhren 1167 - 1176 10 Objekte Lampen 1177 - 1209 33 Objekte Bücher 1210 - 1249 40 Objekte Künstlerindex TIPP: Sie können im nachfolgenden Auktionskatalog die Objekttitel anklicken um ein ausführliches Expose des Objektes (PDF-Format inklusive Bilder) von unserem Webserver abzurufen. Zurück zum Inhaltsverzeichnis Katalog erstellt am 13.05.2013 auf www.auktionshaus-aldag.de - Seite 1 von 142 Ottensener Weg 10, 21614 Buxtehude, Telefon 04161-81005, Telefax 04161-86096, eMail [email protected] Kunst- und Auktionshaus Eva Aldag Gemälde 1 Paul Paeschke (1875 - 1943) - Öl auf Leinwand, "Russischer Markt" 950,00 EUR unten links handsigniert "Paul Paeschke", verso auf dem Keilrahmen alter Ausstellungs-Aufkleber Nr. 664, "buntes Markttreiben mit reicher Figurenstaffage", guter Erhaltungszustand - gerahmt, Bildmaße: 86cm x 110cm, Gesamtmaße: 91cm x 116cm Klicken Sie hier für weitere Informationen zum Künstler 2 Adolf Baumgartner (1850 - 1924) gen. Constantin Stoiloff - Öl auf Leinwand, "Silbertransport in der ... 3.500,00 EUR unten links handsigniert "A. -

THE RUSSIAN SALE Wednesday 6 June 2018

THE RUSSIAN SALE Wednesday 6 June 2018 THE RUSSIAN SALE Wednesday 6 June 2018 at 3pm 101 New Bond Street, London BONHAMS BIDS ENQUIRIES ILLUSTRATIONS 101 New Bond Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 London Front cover: Lot 38 London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Daria Khristova Back cover: Lot 16 To bid via the internet please visit +44 (0) 20 7468 8338 Inside front: Lot 25 www.bonhams.com www.bonhams.com [email protected] Inside back: Lot 8 Opposite page: Lot 48 VIEWING Please provide details of the Cynthia Coleman Sparke Sunday 3 June 2018 lots on which you wish to place +44 (0) 20 7468 8357 To submit a claim for refund of 11am to 3pm bids at least 24 hours prior to [email protected] VAT, HMRC require lots to be Monday 4 June 2018 the sale. exported from the EU within strict 9am to 4.30pm Sophie Law deadlines. For lots on which Tuesday 5 June 2018 New bidders must also provide +44 (0) 207 468 8334 Import VAT has been charged 9am to 4.30pm proof of identity when submitting [email protected] (marked in the catalogue with a *) Wednesday 6 June 2018 bids. Failure to do this may result lots must be exported within 30 9am to 12.30pm in your bids not being processed. Stefania Sorrentino days of Bonhams’ receipt of pay- +44 (0) 20 7468 8212 ment and within 3 months of the SALE NUMBER Bidding by telephone will only be stefania.sorrentino@ sale date.