Consideration of Contemporary Russian Paintings (Revised Edition) ―The Tale of My Collection―

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Аукцион Русское Искусство Auction “Russian Art”

Аукцион Русское Искусство Leonid Shishkin Gallery Четверг 25 ноября 2010 since 1989 Галерея Леонида Шишкина основана в 1989 году • 25 ноября 2010 АУКЦИОН № 96 • Лот № 28 ГАЛЕРЕЯ ЛЕОНИДА ШИШКИНА Auction in Radisson Royal Hotel, Moscow Auction “Russian Art” (Ukraina Hotel) Thursday 25 November 2010 www.shishkin-gallery.ru +7 495 694 35 10 Leonid Shishkin Gallery since 1989 Аукцион 25 ноября 2010 46 111 LEONID SHISHKIN GALLERY Аукцион 25 ноября 2010 АУКЦИОН № 96 «РУССКОе искусствО» Cледующие аукционы: 9 декабря 2010, четверг 19:30 в помещении Галереи на Неглинной, 29 16 декабря 2010, четверг 19:30 (Предновогодняя распродажа. Аукцион без резервных цен) в помещении Галереи на Неглинной, 29 17 февраля 2010, четверг 19:30 Гостиница «Рэдиссон Ройал» («Украина») auction № 96 “RuSSIAN aRt” Next auCtioNs: thursday 9 December 2010, 7.30 p.m. Leonid Shishkin Gallery — 29, neglinnaya Street thursday 16 December 2010, 7.30 p.m. Leonid Shishkin Gallery — 29, neglinnaya Street (christmas Sale without reserve prices) thursday 17 February 2010, 7.30 p.m. Radisson Royal Hotel, Moscow (ukraina Hotel) Галерея Леонида Шишкина Основана в 1989 году www.shishkingallery.ru Член Международной конфедерации антикваров Од на из пер вых ча ст ных га ле рей Мос- One of the oldest and most respect- и арт-дилеров снг и России к вы с без уп реч ной 20-лет ней ре пу та- able galleries with 20 years of reputable ци ей, спе ци а ли зи ру ет ся на рус с кой excellence. Specializes in Russian Art of жи во пи си XX ве ка. the 20th century. С 2000 го да про во дит ре гу ляр ные Holds regular auctions of Soviet paint- аук ци о ны. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

The Institute of Modern Russian Culture

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 61, February, 2011 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089‐4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740‐2735 or (213) 743‐2531 Fax: (213) 740‐8550; E: [email protected] website: hƩp://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the sixty-first biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in August, 2010. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the fall and winter of 2010. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2010 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 for overseas airmail). RUSSIA If some observers are perturbed by the ostensible westernization of contemporary Russia and the threat to the distinctiveness of her nationhood, they should look beyond the fitnes-klub and the shopping-tsentr – to the persistent absurdities and paradoxes still deeply characteristic of Russian culture. In Moscow, for example, paradoxes and enigmas abound – to the bewilderment of the Western tourist and to the gratification of the Russianist, all of whom may ask why – 1. the Leningradskoe Highway goes to St. Petersburg; 2. the metro stop for the Russian State Library is still called Lenin Library Station; 3. there are two different stations called “Arbatskaia” on two different metro lines and two different stations called “Smolenskaia” on two different metro lines; 4. -

The Institute of Modern Russian Culture

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 62, August, 2011 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089‐4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740‐2735 Fax: (213) 740‐8550; E: [email protected] website: hp://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the sixty-second biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in February, 2011. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the spring and summer of 2011. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2010 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 for overseas airmail). RUSSIA To those who remember the USSR, the Soviet Union was an empire of emptiness. Common words and expressions were “defitsit” [deficit], “dostat’”, [get hold of], “seraia zhizn’” [grey life], “pusto” [empty], “magazin zakryt na uchet” [store closed for accounting] or “na pereuchet” [for a second accounting] or “na remont” (for repairs)_ or simply “zakryt”[closed]. There were no malls, no traffic, no household trash, no money, no consumer stores or advertisements, no foreign newspapers, no freedoms, often no ball-point pens or toilet-paper, and if something like bananas from Cuba suddenly appeared in the wasteland, they vanished within minutes. -

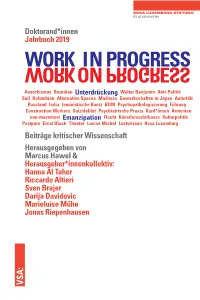

Workonprogress Work in Progress On

STUDIENWERK Doktorand*innen Jahrbuch 2019 ORK ON PROGRESS WORK INPROGRESS ON Anarchismus Bourdieu Unterdrückung Walter Benjamin Anti-Politik Exil Kolumbien Alternative Spaces Madness Gewerkschaften in Japan Autorität Russland India feministische Kunst BDM Psychopathologisierung Führung Construction Workers Suizidalität Psychiatrische Praxis Kurd*innen Armenien non-movement Emanzipation Flucht Künstlersozialkasse Kulturpolitik Postporn Ernst Bloch Theater Louise Michel Lustwissen Rosa Luxemburg Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel & Herausgeber*innenkollektiv: Hanna Al Taher Riccardo Altieri Sven Brajer Darija Davidovic Marieluise Mühe Jonas Riepenhausen VSA: WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS Doktorand*innen-Jahrbuch 2019 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS. Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Doktorand*innenjahrbuch 2019 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel Herausgeber*innenkollektiv: Hanna Al Taher, Riccardo Altieri, Sven Brajer, Darija Davidovic, Marieluise Mühe und Jonas Riepenhausen VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de/studienwerk Die Doktorand*innenjahrbücher 2012 (ISBN 978-3-89965-548-3), 2013 (ISBN 978-3-89965-583-4), 2014 (ISBN 978-3-89965-628-2), 2015 (ISBN 978-3-89965-684-8), 2016 (ISBN 978-3-89965-738-8) 2017 (ISBN 978-3-89965-788-3), 2018 (ISBN 978-3-89965-890-3) der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung sind ebenfalls im VSA: Verlag erschienen und können unter www.rosalux.de als pdf-Datei heruntergeladen werden. Dieses Buch wird unter den Bedingungen einer Creative Com- mons License veröffentlicht: Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License (abrufbar un- ter www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode). Nach dieser Lizenz dürfen Sie die Texte für nichtkommerzielle Zwecke vervielfältigen, ver- breiten und öffentlich zugänglich machen unter der Bedingung, dass die Namen der Autoren und der Buchtitel inkl. -

Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/98 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Wendy Rosslyn is Emeritus Professor of Russian Literature at the University of Nottingham, UK. Her research on Russian women includes Anna Bunina (1774-1829) and the Origins of Women’s Poetry in Russia (1997), Feats of Agreeable Usefulness: Translations by Russian Women Writers 1763- 1825 (2000) and Deeds not Words: The Origins of Female Philantropy in the Russian Empire (2007). Alessandra Tosi is a Fellow at Clare Hall, Cambridge. Her publications include Waiting for Pushkin: Russian Fiction in the Reign of Alexander I (1801-1825) (2006), A. M. Belozel’skii-Belozerskii i ego filosofskoe nasledie (with T. V. Artem’eva et al.) and Women in Russian Culture and Society, 1700-1825 (2007), edited with Wendy Rosslyn. Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture Edited by Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi Open Book Publishers CIC Ltd., 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2012 Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial -

The 12 Days of Christmas

MOSCOW DECEMBER 2010 www.passportmagazine.ru THE 12 DAYS OF CHRISTMAS Why Am I Here? The Master of Malaya Bronnaya The 1991 Coup from atop the White House Sheffi eld Joins the Space Race Christmas Tipples The English word for фарт December_covers.indd 1 22.11.2010 14:16:04 December_covers.indd 2 22.11.2010 14:57:06 Contents 3. Editor’s Choice Alevitina Kalinina and Olga Slobodkina 8. Clubs Get ready Moscow, nightlife’s evolving! Max Karren- berg, DJs Eugene Noiz and Julia Belle, Imperia, Poch Friends, Rai Club, Imperia, Harleys and Lamborghinis, Miguel Francis 8 10. Theatre Review Play Actor & Uncle Vanya at the Tabakov Theatre. Don Juan at The Bolshoi Theatre, Our Man from Havanna at The Malaya Bronnaya Theatre, Por Una Cabeza and Salute to Sinatra at The Yauza Palace, Marina Lukanina 12. Art The 1940s-1950s, Olga Slobodkina Zinaida Serebriakova in Moscow, Ross Hunter 11 16. The Way it Was The Coup, John Harrison Inside the White House, John Harrison UK cosmonaut, Helen Sharman, Helen Womack Hungry Russians, Helen Womack 20. The Way It Is Why I Am Here part II, Franck Ebbecke 20 22. Real Estate Moscow’s Residential Architecture, Vladimir Kozlev Real Estate News, Vladimir Kozlev 26. Your Moscow The Master of Malaya Bronnaya, Katrina Marie 28. Wine & Dining New Year Wine Buyer Guide, Charles Borden 26 Christmas Tipples, Eleanora Scholes Tutto Bene (restaurant), Mandisa Baptiste Restaurant and Bar Guide Marseille (restaurant), Charles Borden Megu, Charles Borden 38. Out & About 42. My World Ordinary Heroes, Helen Womack 38 Dare to ask Deidre, Deidre Dare 44. -

Resilient Russian Women in the 1920S & 1930S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 8-19-2015 Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Russian Literature Commons, Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s" (2015). Zea E-Books. Book 31. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/31 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Marcelline Hutton Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s The stories of Russian educated women, peasants, prisoners, workers, wives, and mothers of the 1920s and 1930s show how work, marriage, family, religion, and even patriotism helped sustain them during harsh times. The Russian Revolution launched an economic and social upheaval that released peasant women from the control of traditional extended fam- ilies. It promised urban women equality and created opportunities for employment and higher education. Yet, the revolution did little to elim- inate Russian patriarchal culture, which continued to undermine wom- en’s social, sexual, economic, and political conditions. Divorce and abor- tion became more widespread, but birth control remained limited, and sexual liberation meant greater freedom for men than for women. The transformations that women needed to gain true equality were post- poned by the pov erty of the new state and the political agendas of lead- ers like Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin. -

Italy Too Sweet. Russian Landscape Painters Travelling Central Europe. the Case of Savrasov and Shishkin

kunsttexte.de/ostblick 3/2016 - 1 >an ZachariáF Italy too sweet. !ussian landsca e ainters tra)ellin, central $uro e. =he case o" 6a)raso) and 6hishkin I. Introduction It seems that nowadays, just as in the ast, any re- to e0ual3 but e0ually dif"icult to de art "rom. =here- search area related to !ussia and its art is contamin- "ore, !ussian ainters "ollowed the ath su,,ested by ated with the issue o" the #East or %est& binary writers long into the 19th century.4 scheme that has been resent in notions o" !ussia at !ussian landsca e ainting was "ormed through a least since 'yotr Chaadaye)*s 'hiloso hical +etters.1 com licated dialo,ue between the !ussian academic %ith res ect to the rather modest develo ment o" tradition 9the 6t. 'etersburg 4cademy and the 7o- !ussian landsca e ainting, enca sulated rou,hly scow 6chool o" 'ainting, 6culpture and 4rchitecture<, within the two decades "rom 1850 to 1870, I will ur- ,radual learning about Euro ean art roduction and sue the following related questions: Is it permissible to the develo ing !ussian tradition resulting in the work consider landsca e ainting in the scheme o" #East- o" the 'eredvizhniki and their circle. =he aim o" this ern& or #!ussian& versus #%estern& or #Euro ean&2 study is to com are !ussian landsca e ainting o" and %hat was the role o" travel and migration o" the 1850s to the 1870s with the e0uivalent art produc- artists and works o" art in the ,enesis o" the ima,e o" tion o" Central and %estern Euro e with which !ussi- the Russian landsca e in the fine arts. -

Russian Art & History

RUSSIAN ART & HISTORY HÔTEL MÉTROPOLE MONACO 7-8 JULY 2020 FRONT COVER: LOT 217 - SOVIET PORCELAIN Propaganda Plate ‘History of the October Takeover. 1917’ ABOVE: LOT 18 - NIKOLAY ROERICH The Borodin’s opera “Prince Igor”, 1914 LOT 333 - BALMONT K.D., AUTOGRAPH Handwritten collection of poems PAR LE MINISTERE DE MAITRE CLAIRE NOTARI HUISSIER DE JUSTICE A MONACO RUSSIAN ART & HISTORY RUSSIAN ART TUESDAY JULY 7, 2020 - 14.00 FINE ART & OBJECTS OF VERTU WEDNESDAY JULY 8, 2020 - 14:00 AUTOGRAPHS, MANUSCRIPTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS WEDNESDAY JULY 8, 2020 - 17:00 Hotel Metropole - 4 avenue de la Madone - 98000 MONACO PREVIEW BY APPOINTMENT www.hermitagefineart.com Inquiries - tel: +377 97773980 - Email: [email protected] 25, Avenue de la Costa - 98000 Monaco Tel: +377 97773980 www.hermitagefineart.com Sans titre-1 1 26/09/2017 11:33:03 SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES In-house experts Hermitage Fine Art expresses its gratitude to Anna Burovа for help with descriptions of the decorative objects of art. Hermitage Fine Art would like to express its gratitude to Igor Elena Efremova Maria Lorena Anna Chouamier Evgenia Lapshina Sergey Podstanitsky Kouznetsov for his Director Franchi Deputy Director Expert Specially Invited support with IT. Deputy Director Manuscripts & Expert and Advisor rare Bookes Paintings (Moscow) Catalogue Design: Darya Spigina Photography: François Fernandez Eric Teisseire Yolanda Lopez Franck Levy Elisa Passaretti Georgy Latariya Yana Ustinova Administrator Accountant Auction assistant Expert Invited Expert Icons Russian Decorative Arts Ivan Terny Stephen Cristea Sergey Cherkashin Auctioneer Auctioneer Invited Advisor Translator and Editor (Moscow) TRANSPORTATION LIVE AUCTION WITH 8 1• AFTER GÉRARD DE LA BARTHE (1730-1810), EARLY XIX C. -

The Pal Use Heritage C Mm Ner

THE PAL USE HERITAGE C MM NER “School & Library” Hallowed Harvests Color Gallery Plates (Part 1) The color gallery images featured here generally follow the sequence of their description in the text of the online “School & Library” blog postings. PLATE 1: Correlation of Ancient Ritual and Agricultural Calendars with Crop Sequences GC: Gezer Calendar HR: Hebrew Ritual PC: Primitive Christian aVariations of specific dates due to the lunar cycle with Mediterranean seasons typically two to three months earlier than in northern Europe. bEarly Christian calendar based on Philip Carrington. cChristmas designated as a holy day after the 1st century. dEpiphany, also known as Theophany in the Orthodox tradition, originally celebrated the baptism of Jesus by John but soon also came to commemorate his “manifestation” to the Wise Men and wider world. eJewish civil holidays PLATE 2: Zliten Threshing Mosaic (c. 200 AD) 22 ⅘ x 22 ⅘ inches Detail showing Libyan coloni leading horses and oxen, Archaeological Museum, Tripoli Wikimedia Commons PLATE 3. Hildegard of Bingen, The Wheel of Life Detail showing harvest reaper at center left Codex Latinus 1492 (Liber Divinorum Operum) State Library, Lucca, Italy Wikimedia Commons PLATES 4 & 5. Limbourg Brothers, “July” and “August” Les Très Riches Heures du Jean, Duc de Berry (c. 1415) Illuminated parchment, 11 ⅘ x 8 ½ inches Musée Condé, Chantilly, France Wikimedia Commons PLATE 6. Heironymus Bosch, The Path of Life with The Haywain (c. 1505) Oil and tempura on wood; 53 x 79 inches Museo del Prado, Madrid Wikimedia Commons PLATE 7. Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Harvesters (1565) Oil on wood, 45⅞ x 62⅞ inches Rogers Fund, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Wikimedia Commons PLATE 8. -

Les Echos De Phil

Les Echos de Phil. Le train-train du chef de gare. Périodique aléatoire n°7 du 1er novembre 2008. Zinaida Serebriakova (1884 – 1967). Zinaida Yevgenyevna Serebriakova est née près de Karkov en Ukraine en 1884. Elle a fait des études artistiques à Saint-Pétersbourg dans l’école de la Princesse Tenisheva. Elle a séjourné en Italie de 1902 à 1903, puis elle a travaillé dans l’atelier de Osip Braz à Saint-Pétersbourg et a passé deux ans à l’Académie de la Grande Chaumière à Paris. Récolte 1915. Autoportrait à la table d’habillage 1909. Après avoir connu une période de bonheur et de Autoportrait de Zinaida Serebriakova en 1921 et Lithographie de prospérité avant la révolution bolchevique, elle allait Zinaida Serebriakova par G. Vereiky en 1922. partager le destin tragique de nombreux de ses compatriotes. Elle perd son mari et doit élever, seule et avec très peu de ressources, ses quatre enfants. Elle s’exile en France et est séparée de deux de ses enfants qu’elle ne reverra que 36 ans plus tard ! Zinaida Serebriakova exprime au travers de ses œuvres son amour du monde et de sa beauté, particulièrement par des peintures de la campagne russe et de ses habitants. Elle excelle aussi dans la manière avec laquelle elle représente la sensualité et l’érotisme de la femme au travers de ses nombreux tableaux de nus. Nu dormant 1931. important, en limitant notamment la pullulation des chenilles et escargots. Bien que l'espèce fasse partie des coléoptères, la femelle ne peut pas voler et porte le nom de "ver".