Among the the Name of Many Poems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Ottoman Poetry

; All round a thousand nightingales and many an hundred lay. ' Come, let us turn us to the Court of Allah: Still may wax The glory of the Empire of the King triumphant aye, 2 So long as Time doth for the radiant sun-taper at dawn A silver candle-stick upon th' horizon edge display, ^ Safe from the blast of doom may still the sheltering skirt of Him Who holds the world protect the taper of thy life, we pray. Glory the comrade, Fortune, the cup-bearer at thy feast; * The beaker-sphere, the goblet steel-enwrought, of gold inlay ! I give next a translation of the famous Elegy on Sultan Suleyman. It is, as usual, in the terkib-bend form. There is one other stanza, the last of all, which I have not given. It is a panegyric on Suleyman's son and successor Selim II, such as it was incumbent on Baqi, in his capacity of court poet, to introduce into a poem intended for the sovereign but it strikes a false note, and is out of harmony with, and altogether unworthy of, the rest of the poem. The first stanza is addressed to the reader. Elegy on Sultan Sulcym;in. [214] thou, fool-tangled in the incsli of fame and glory's snare! How long this lusl of things of 'I'linc lliat ceaseless lluwolli o'er? Hold tliou in mitiil thai day vvliicli shall be hist of life's fair spring, When Mii:<ls the I uli|)-tinlcd cheek to auluniu-lcaf must wear, » Wiieii lliy lasl (Iwclling-placc must Ije, e'en like tlie dregs', tlic diisl, « When mi<l ihe iiowl of cheer must fail the stone I'injc's haml doth licar. -

A History of Ottoman Poetry

20I sionally, but not often, tells a story, and sometimes indulges in a little fine language. He is, moreover, the last Tezkire- writer to attempt a complete survey of the field of Ottoman poetry, to start at the' beginning and carry the thread down to the time of writing. The subsequent biographers take up the story at about the point where it is left off by the preceding writer to whose work they mean their own to be a continuation, always bringing the history down to the year in which they write. Riyazi was a poet of some distinction, and as we shall have occasion to speak of his career more fully later on, it is enough to say here that he was born in 980 (1572— 3) and died in 1054 (1644). His Tezkirc, which is of very con- siderable value, is dedicated to Sultan Ahmed I and was begun in the year 10 16 (1607 — 8) and completed in the Rejcb of 10 1 8 (1609). In the preface the author takes credit to himself, justly enough, for having avoided prolixity in language, lest it should prove a 'cause of weariness to the reader and the writer.' He also claims to be more critical than his predecessors who, he says, have inserted in their 'iczkires poets and poetasters alike, while he has admitted the poets (Jiily, turning the others out. In like manner he has perused the entire wcjrks of nearly all the poets he inchules, and chosen as examples such verses only as are really worthy of commendation, while the otlu-r biographers iiave not given themselves this trouble, {•"iiially, lie professes to he \n:yU:rA\y inipaifial in his criticisms, cxtollin).; no man !>) nason ol Im(Im1'.1ii|) 01 coniniinnt )' o| aitn, and \\ it hholdint; due IHiiiM- liMHi none !)(•(, Ill, (• III |)(i soiial aversion. -

Pan-Eurasian Expansions, Ca. 1400–1600

part one Pan-Eurasian Expansions, ca. 1400–1600 1 Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations Persian Learning in the Ottoman World Murat Umut Inan The preface to the 1504 commentary on the introduction to the Gulistan (Rose Garden) of Sa‘di (d. 1292) of the Ottoman scholar Lami‘i Çelebi (d. 1532), a Naqshbandi Sufi translator of the Timurid-era Sufi poet ‘Abd al-Rahman Jami (d. 1492), begins: It should be known that Persian is a language built upon beauty and elegance. Dari is another name of Persian. Lexicographers explain the reason [why Persian is also called Dari] as follows: Bahram Gur forbade the people in his palace to speak in Persian and to write the letters and edicts in Persian. Because at that time the language became associated with his palace, people called it Dari. Since this language is founded on elegance, its alphabet does not include many letters [that ,Second .[ث] ”are found in the Arabic alphabet]. First, it does not have the letter “s The words that are pronounced in this language .[ح] ”it does not have the letter “h are either of Arabic origin or borrowed from another language or have [ح] ”with “h which is a common word in ,[ﺤﻴﺰ] ”been corrupted by common use. The word “hiz but people ,[ﻩ] ”Persian, means catamite. This word was originally spelled with “h As a .[ح] ”have corrupted the word, pronounced it harshly and spelled it with “h matter of fact, if one looks at Asadi Tusi’s [d. 1072–73] Mustashhadat [Evidences], Hindushah Nakhichawani’s [d. ca. -

A History of Ottoman Poetry

. 'God hath Treasuries aneath the Throne, the Keys whereof are the Tongues of the Poets.' H a d i s - i S h e r i f HISTORY OF OTTOMAN POETRY BY THE LATE E. J. W. GIBB, M. R. A. S. VOLUME II EDITED BY EDWARD G. BROWNE, M. A., M. B., SIR THOMAS ADAMS' PROFESSOR OF ARABIC AND FEIJ.OW OF PEMBROKE COLLEGE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE. LONDON LUZAC & CO., GREAT RUSSELL STREET 1902 LEYDEN. PRINTED HY E. J. BRILL. EDITOR'S PREFACE. The sad circumstances which led to my becoming respon- sible for the editing of this and the succeeding volumes of the History of Ottoman Poetry are known to all those who are interested in Oriental scholarship, and are fully set forth in the Athenaeum for January i8, 1902, pp. 81 — 82, and the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society for April, 1902, pp. 486 —489. Nevertheless it seems to me desirable to begin my Preface to this the first posthumous volume of my late friend's great and admirable work with a brief notice of his life, a life wholly devoted and consecrated to learning and fruitful labour of research, but cut short, alas! in its very prime by premature and unexpected death. Elias John Wilkinson Gibb was born at Glasgow on June 3, 1857, and received his education in that city, first at Park School under Dr. Collier, the author of the History of England, and afterwards at the University. It appears that him from an early age linguistic studies especially attracted ; but I have not been able to ascertain exactly how and when his attention first became directed to the Ofient, though I believe that here, as in many other cases, it was the fascination of the Arabian A'ights which first cast over him the spell of the East. -

A Millennium of Turkish Literature (A Concise History)

A Millennium of Turkish Literature (A Concise History) by TALAT S. HALMAN edited by Jayne L. Warner REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM PUBLICATIONS © Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 3164 Handbook Series 5 ISBN: 978-975-17-3374-0 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Halman, Talat S. A Millenium of Turkish literature / Talat S. Halman: Edited by Jayne L. Warner.- Second Ed. - Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2009. 224 pp.: col. ill.; 20 cm.- (Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications; 3164. Handbook Series of General Directorate of Libraries and Publications: 5) ISBN: 978-975-17-3374-0 I. title. II. Warner, Jayne L. III. Series. 810 Cover Kâşgarlı Mahmud, Map, Divanü Lügâti’t Türk Orhon Inscription Printed by Fersa Ofset Baskı Tesisleri Tel: 0 312 386 17 00 Fax: 0 312 386 17 04 www.fersaofset.com First Edition Print run: 5000. Printed in Ankara in 2008. Second Edition Print run: 5000. Printed in Ankara in 2009. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword: A Time-Honored Literature 5 Note on Turkish Spelling and Names 11 The Dawn in Asia 17 Selçuk Sufism 31 Ottoman Glories 49 Timeless Tales 83 Occidental Orientation 93 Republic and Renascence 115 Afterword: The Future of Turkish Literature 185 Suggested Reading 193 Biographical Notes 219 - 4 - Foreword A TIME-HONORED LITERATURE - 5 - ROM O RHON INSCRIPTIONS TO O RHAN P AMUK. That could serve as a definition of the life-story of F Turkish Literature from the eighth century A.D. -

AHDI`S GÜLŞEN-Î ŞUARÂ: an Unusual Example of Biographical Dictionary of Poets

AHDI`S GÜLŞEN-Î ŞUARÂ: An Unusual Example of Biographical Dictionary of Poets RESEARCH ARTICLE Ph. D. Candidate: Nilab SAEEDİ İbn Haldun Universitesi Tarih Bölümü (Ph.D.) [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0001-7729-9563 Gönderim Tarihi: 19.05.2020 Kabul Tarihi: 15.12.2020 Alıntı: SAEEDİ, N. (2020). Ahdı`S Gülşen-Î Şuarâ: An Unusual Example of Biographical Dictionary of Poets, AHBV Akdeniz Havzası ve Afrika Medeniyetleri Dergisi, 2(2),180-186. ABSTRACT: Şair Tezkires are an important source of information. For history-writing and literature, biographies have played an important role. Important for XVI Century Ahdi’s Gülşen-i Şuara written in 1564 is the fourth Şair Tezkire exam- ple in Ottoman Turkish. Among many Şair Tezkires in Ottoman literature, Ahdi`s work is different than others. This work is an important source of information for poets around Baghdad. The Biographical Dictionary of Poets provided in Gülşen- i Şuara is hard to find anywhere else. Another important point which makes Gülşen-i Şuaraa worthy text is Ahdi himself. Being from Baghdad he showcases an Arabic perspective inside his text in Ottoman Turkish. A very strong argument comes out of reading Ahdi, is an outsider perspective of the Ottoman. Ahdi comes out of the text as a devoted personality. He makes sure to mention all the religious information inside the text. While no classification is given inside the text but a non-stated classification comes out as the text continues. Ahdi before moving to poets, tries to introduce poets in different classes of the Ottoman empire. Keywords: Ahdi, XVI-Century, Tezkire, Biography, Ottoman Literature Ahdi`nin Gülşen-î Şuarâ'sı Şair Tezkirelerinde Sıradışı Bir Örneği ÖZ: Şair Tezkireleri önemli bir bilgi kaynağıdır. -

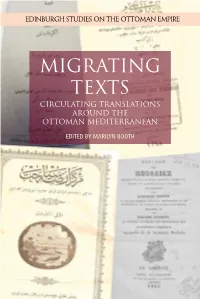

Migrating Texts

MARILYN BOOTH MARILYN Explores translation in the context of the late Ottoman Mediterranean world EDITED BY EDINBURGH STUDIES ON THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE Fénelon, Offenbach and the Iliad in Arabic, Robinson Crusoe in Turkish, the Bible in Greek-alphabet Turkish, excoriated French novels circulating through the Ottoman Empire in Greek, Arabic and Turkish – literary translation at the eastern end of the Mediterranean offered worldly vistas and new, hybrid genres to emerging literate audiences in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Whether to propagate ‘national’ language reform, circulate the Bible, help Migrating audiences understand European opera, argue for girls’ education, institute pan-Islamic conversations, introduce political concepts, share the Persian Gulistan with Anglophone readers in Bengal, or provide racy fiction to schooled adolescents in Cairo and Istanbul, translation was an essential tool. texts But as these essays show, translators were inventors. And their efforts might yield surprising results. Circulating Translations around the Key Features • A substantial introduction provides in-depth context to the essays that Ottoman Mediterranean MIGRATING TEXTS follow • Nine detailed case studies of translation between and among European EDITED BY MARILYN BOOTH and Middle-Eastern languages and between genres • Examines translation movement from Europe to the Ottoman region, and within the latter • Looks at how concepts of ‘translation’, ‘adaptation’, ‘arabisation’, ‘authorship’ and ‘untranslatability’ were understood by writers (including translators) and audiences • Challenges views of translation and text dissemination that centre ‘the West’ as privileged source of knowledge Marilyn Booth is Khalid bin Abdullah Al Saud Professor in the Study of the Contemporary Arab World at the University of Oxford. She is author and editor of several books including Classes of Ladies of Cloistered Spaces: Writing Feminist History through Biography in Fin-de-siècle Egypt (Edinburgh University Press, 2015). -

TRAVELLING SEXUALITIES, CIRCULATING BODIES, and EARLY MODERN ANGLO-OTTOMAN ENCOUNTERS by Abdulhamit Arvas a DISSERTATION Submit

TRAVELLING SEXUALITIES, CIRCULATING BODIES, AND EARLY MODERN ANGLO-OTTOMAN ENCOUNTERS By Abdulhamit Arvas A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of English—Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT TRAVELLING SEXUALITIES, CIRCULATING BODIES, AND EARLY MODERN ANGLO-OTTOMAN ENCOUNTERS By Abdulhamit Arvas Travelling Sexualities, Circulating Bodies, and Early Modern Anglo-Ottoman Encounters explores intricate networks and connections between early modern English and Ottoman cultures. In particular, it traces connected sexual histories and cultures between the two contexts with a focus on the abduction, conversion, and circulation of boys in cross-cultural encounters during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It argues that the textual, aesthetic template of the beautiful abducted boy—i.e. Ganymede, the Indian boy of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream , the Christian boy in Ottoman poetry—intersects with the historical figure of vulnerable youths, who were captured, converted, and exchanged within the global traffic in bodies. It documents the aesthetic, erotic, and historical deployments of this image to suggest that the circulation of these boys casts them as subjects of servitude and conversion, as well as objects of homoerotic desire in the cultural imaginary. The project thereby uncovers the tensions and dissonances between the aestheticized eroticism of cultural representations and the coercive and violent history of abductions, conversions, and enslavements -

Avtoreferat – Qissa

REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN On the rights of the manuscript ABSTRACT of the dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy LIFE AND CREATIVITY OF RUHI BAGHDADI Specialty: 5717.01 – Literature of the Turkic peoples Field of science: Philology Applicant: Shohrat Alvand Salimov Baku – 2021 The dissertation work was carried out at the Institute of Manuscripts named after Mohammad Fuzuli of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences. Scientific supervisor: Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor Azada Shahbaz Musayeva Official opponents: Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor Asgar Adil Rasulov Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor Firuza Abdulla Agayeva Doctor of Philological Sciences, Associate Professor Almaz Gasim Binnatova Dissertation council FD –1.18 of Supreme Attestation Commission under the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan operating under the Institute of Oriental Studies named after Academician Ziya Bunyadov, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences Doctor of Philosophy in Philology, Associate, Professor Khanimzar Ali Karimova Elman Hilal Guliyev 2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE WORK Relevance and development of the topic. The 16th century is one of the most powerful and important periods of development of the Ottoman and Azerbaijani state of Safavids. The wars in the territories of the Ottoman and Azerbaijani state of Safavids, which reached a great political and economic level, at the same time had a serious impact on the economy of both countries, part of the population was relocated to remote areas and forced to leave their homes. All this, of course, is reflected in the literary works, which play the role of a reliable source as historical sources. This period is also important for the rapid development of Azerbaijani-Turkish literary relations. -

The Appropriation of Islamic History and Ahl Al- Baytism in Ottoman Historical Writing, 1300-1650

THE APPROPRIATION OF ISLAMIC HISTORY AND AHL AL- BAYTISM IN OTTOMAN HISTORICAL WRITING, 1300-1650 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philisophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Vefa Erginbaş, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee Jane Hathaway, Advisor Stephen Dale Dale K. Van Kley ii Copyright by Vefa Erginbaş 2013 iii Abstract This is a study of Ottoman historical productions of the pre-1700 period that deal directly with narratives of early Islamic history. It specifically deals with the representations of the formative events of early Islamic history. Through the lenses of universal histories, biographies of Muhammad, religious treatieses and other narrative sources, this study examines Ottoman intellectuals’ perceptions of the events that occurred after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 C.E. It particularly provides a perspective on issues such as the problem of succession to Muhammad as leader of the Muslim community; the conflict between ‘Alī ibn Abī Talīb and Mu‘āwiyah and the Umayyad dynasty’s assumption of the position of successor (caliph); and Ottoman views of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs and significant events and persons during the reigns of these two dynasties. Since the great schism between the Sunnis and Shiites began because of their different stances on the issue of succession to Muhammad, studying these perceptions can help to tell us whether the Ottomans were strict Sunnis who favored a rigidly Sunni interpretation of the formative events of Islam. After the death of Muhammad, the Muslim community was divided over how his successor as leader of the community should be chosen. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Early Enlightenment In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Early Enlightenment in Istanbul A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History and Science Studies by Bekir Harun Küçük Committee in charge: Professor Robert S. Westman, Chair Professor Frank P. Biess Professor Craig Callender Professor Luce Giard Professor Hasan Kayalı Professor John A. Marino 2012 Copyright Bekir Harun Küçük, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Bekir Harun Küçük is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii DEDICATION To Merve iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Table of Contents . v List of Figures . vi List of Tables . vii Acknowledgements . viii Vita and Publications . xi Abstract of the Dissertation . xiii Chapter 1 Early Enlightenment in Istanbul . 1 Chapter 2 The Ahmedian Regime . 42 Chapter 3 Ottoman Theology in the Early Eighteenth Century . 77 Chapter 4 Natural Philosophy and Expertise: Convert Physicians and the Conversion of Ottoman Medicine . 104 Chapter 5 Contemplation and Virtue: Greek Aristotelianism at the Ottoman Court . 127 Chapter 6 The End of Aristotelianism: Upright Experience and the Printing Press . 160 Chapter 7 L’Homme Machine . 201 Bibliography . 204 v LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: The title page of Cottunius’s Commentarii. 131 Figure 2: Johannes Cottunius’s portrait from the Commentarii (1648). 146 Figure 3: Cottunius’s titles according Matteo Bolzetta’s preface to Icones graeco- rum sapientium (1657). 147 Figure 4: A hand-drawn illustration comparing the Copernican and Tychonic models for the universe from Mecmu,at-ı Hey -etü’l-K.