Malbim's Approach to the Sins of Biblical Personages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Arba 'Ah Turim of Rabbi Jacob Ben Asher on Medical Ethics, ” Rabbi David Fink, Ph.D

Arba`ah Turim of Rabbi Jacob ben Asher on Medical Ethics Rabbi David Fink, Ph.D. Rabbi Jacob ben Asher was a leading halachic authority of the early part of the fourteenth century. As a young man he accompanied his father, Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh), from Germany to Spain. In Toledo he wrote a number of basic halachic and exegetical works. The most important of these are the Arba`ah Turim, which later became the basis of Rabbi Joseph Karo’s Shulchan Aruch. The following passage is taken from section 336 of the second book (Yoreh De`ah) of the Arba`ah Turim. It deals with the obligations of medical practitioners. Rabbi Jacob’s opinions on this topic became the subject of commentary and analysis by the leading halachic scholars of subsequent generations. At the School of Rabbi Ishmael it was taught that the verse “And he shall heal (Ex. 21:19)” implies that the physician is permitted to heal.1 One should not disregard pain for fear of making a mistake and inadvertently killing the patient. Rather one must be exceedingly cautious as is proper in any capital case. Further, one should not say that if God has smitten the patient, it is improper to heal him, it being unnatural for mortals to restore health, even though they are accustomed to do so.2 Thus it says, “Yet in his disease he sought not to the Lord, but to the physicians (2 Chr. 16:12)”. From this we learn that the physician is permitted to heal and that healing is a part of the commandment of lifesaving. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

New Contradictions Between the Oral Law and the Written Torah 222

5/7/2019 222 New Contradictions between the Oral Torah and the Written Torah - iGod.co.il Science and faith main New Contradictions Between The Oral Law And The Written Torah 222 Contradictions in the Oral Law Talmud Mishneh Halacha 1/68 /מדע-אמונה/-101סתירות-מביכות-בין-התורה-שבעל-פה-לתורה/https://igod.co.il 5/7/2019 222 New Contradictions between the Oral Torah and the Written Torah - iGod.co.il You may be surprised to hear this - but the concept of "Oral Law" does not appear anywhere in the Bible! In truth, such a "Oral Law" is not mentioned at all by any of the prophets, kings, or writers in the entire Bible. Nevertheless, the Rabbis believe that Moses was given the Oral Torah at Sinai, which gives them the power, authority and control over the people of Israel. For example, Rabbi Shlomo Ben Eliyahu writes, "All the interpretations we interpret were given to Moses at Sinai." They believe that the Oral Torah is "the words of the living God". Therefore, we should expect that there will be no contradictions between the written Torah and the Oral Torah, if such was truly given by God. But there are indeed thousands of contradictions between the Talmud ("the Oral Law") and the Bible (Torah Nevi'im Ketuvim). According to this, it is not possible that Rabbinic law is from God. The following is a shortened list of 222 contradictions that have been resurrected from the depths of the ocean of Rabbinic literature. (In addition - see a list of very .( embarrassing contradictions between the Talmud and science . -

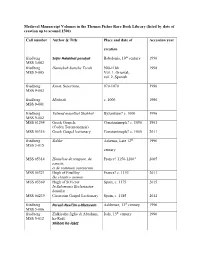

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Listed by Date of Creation up to Around 1500) Call Number Au

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (listed by date of creation up to around 1500) Call number Author & Title Place and date of Accession year creation friedberg Sefer Halakhot pesuḳot Babylonia, 10 th century 1996 MSS 3-002 friedberg Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah 900-1188 1998 MSS 9-005 Vol. 1, Oriental; vol. 2, Spanish. friedberg Kinot . Selections. 970-1070 1996 MSS 9-003 friedberg Mishnah c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-001 friedberg Talmud masekhet Shabbat Byzantium? c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-002 MSS 01244 Greek Gospels Constantinople? c. 1050 1901 (Codex Torontonensis) MSS 05316 Greek Gospel lectionary Constantinople? c. 1050 2011 friedberg Siddur Askenaz, Late 12 th 1996 MSS 3-015 century MSS 05314 Homeliae de tempore, de France? 1150-1200? 2005 sanctis, et de communi sanctorum MSS 05321 Hugh of Fouilloy. France? c. 1153 2011 De claustro animae MSS 03369 Hugh of StVictor Spain, c. 1175 2015 In Salomonis Ecclesiasten homiliæ MSS 04239 Cistercian Gospel Lectionary Spain, c. 1185 2012 friedberg Perush Neviʼim u-Khetuvim Ashkenaz, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-006 friedberg Zidkiyahu figlio di Abraham, Italy, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-012 ha-Rofè. Shibole ha-leḳeṭ friedberg David Kimhi. Spain or N. Africa, 13th 1996 MSS 5-010 Sefer ha-Shorashim century friedberg Ketuvim Spain, 13th century 1996 MSS 5-004 friedberg Beʼur ḳadmon le-Sefer ha- 13th century 1996 MSS 3-017 Riḳmah MSS 04404 William de Wycumbe. Llantony Secunda?, c. 1966 Vita venerabilis Roberti Herefordensis 1200 MSS 04008 Liber quatuor evangelistarum Avignon? c. 1220 1901 MSS 04240 Biblia Latina England, c. -

Title Listing of Sixteenth Century Books

Title Listing of Sixteenth Century Books Abudarham, David ben Joseph Abudarham, Fez, De accentibus et orthographia linguae hebraicae, Johannes Reuchlin, Hagenau, Adam Sikhli, Simeon ben Samuel, Thiengen, Adderet Eliyahu, Elijah ben Moses Bashyazi, Constantinople, Ha-Aguddah, Alexander Suslin ha-Kohen of Frankfurt, Cracow, Agur, Jacob Barukh ben Judah Landau, Rimini, Akedat Yitzhak, Isaac ben Moses Arama, Salonika, Aleh Toledot Adam . Kohelet Ya’akov, Baruch ben Moses ibn Baruch, Venice, – Alfasi (Sefer Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Constantinople, Alfasi (Hilkhot Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Sabbioneta, – Alfasi (Sefer Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Riva di Trento, Alphabetum Hebraicum, Aldus Manutius, Venice, c. Amadis de Gaula, Constantinople, c. Amudei Golah (Semak), Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil, Constantinople, c. Amudei Golah (Semak), Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil, Cremona, Arba’ah ve’Esrim (Bible), Pesaro, – Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Fano, Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Augsburg, Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Constantinople, De arcanis catholicae veritatis, Pietro Columna Galatinus, Ortona, Arukh, Nathan ben Jehiel, Pesaro, Asarah Ma’amarot, Menahem Azariah da Fano, Venice, Avkat Rokhel, Machir ben Isaac Sar Hasid, Augsburg, Avkat Rokhel, Machir ben Isaac Sar Hasid—Venice, – Avodat ha-Levi, Solomon ben Eliezer ha-Levi, Venice, Ayumah ka-Nidgaloth, Isaac ben Samuel Onkeneira, Constantinople, Ayyalah Sheluhah, Naphtali Hirsch ben Asher Altschuler, Cracow, c. Ayyelet -

1 the Image of Jacob Engraved Upon the Throne: Further Reflection on the Esoteric Doctrine of the German Pietists

1 The Image of Jacob Engraved upon the Throne: Further Reflection on the Esoteric Doctrine of the German Pietists Verily, at this time that which was hidden has been revealed because forgetfulness has reached its final limit; the end of forgetfulness is the beginning of remembrance. Abraham Abulafia,'Or ha-Sekhel, MS Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek 92, fol. 59b I One of the most interesting motifs in the world of classical rabbinic aggadah is that of the image of Jacob engraved on the throne of glory. My intention in this chapter is to examine in detail the utilization of this motif in the rich and varied literature of Eleazar ben Judah of Worms, the leading literary exponent of the esoteric and mystical pietism cultivated by the Kalonymide circle of German Pietists in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The first part of the chapter will investigate the ancient traditions connected to this motif as they appear in sources from Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages in order to establish the basis for the distinctive understanding that evolves in the main circle of German Pietists to be discussed in the second part. As I will argue in detail later, the motif of the image of Jacob has a special significance in the theosophy of the German Pietists, particularly as it is expounded in the case of Eleazar. The amount of attention paid by previous scholarship to this theme is disproportionate in relation to the central place that it occupies in the esoteric ruminations of the Kalonymide Pietists. 1 From several passages in the writings of Eleazar it is clear that the motif of the image of Jacob is covered and cloaked in utter secrecy. -

![1] Rabbi Malbim](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5431/1-rabbi-malbim-2095431.webp)

1] Rabbi Malbim

MAHARSHA Rabbi Shmuel Edelles Born 1555, / Yahrzeit date: 5th of Kislev 1631 The first interesting point to mention about this great personality is that his family appellative is feminine; it is the name of his mother in law. How so? It is since she (as a rich widow) supported financially the upkeepof Rabbi Shmuel’s yeshiva, for over 20 years. Only at her decease, and the aid was halted, did that yeshiva cease to exist. Then it was that he received a rabbinical position. In order to show due regard and gratitude, he constantly signed his name by adding thereto her name (“Adelle”). It is also true that his wife was a descendant of the world famous Maharal. (Encyclopedia Otzar Israel, ed. by D. Eisenstein. Some of the forthcoming material in our article we culled from that work). This great rabbi wrote one of the most important commentaries to be able thereby to understand the abstruse Talmudic dialectics. The gaon “Hazzon Ish” advises each and every Yeshiva student to make full use of this Maharsha comentary (“Letters”, beginning of article one; end of article 20) and to paraphrase his words: “It is a boon grant for Kllal Israel, to aid all subsequent generations in the task of understanding the Torah properly”. Maharsha was a genius in logical explanations, and detested false Pilpul, which was rampant in his period (and was also despised by the Sha’loh, Masechet Shevuot, and so too by the Maharal, in his commentary to Avot, pp. 305-306). He charges that false “Hillukim” deter a person from the truth, since each disputant is only vehemently interested in “winning the debate” and is negatively impassioned to disprove the dissenting opinion (Commentary to Bava Metzia 85a “Delishtakach”). -

The Formation of the Talmud

Ari Bergmann The Formation of the Talmud Scholarship and Politics in Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s Dorot Harishonim ISBN 978-3-11-070945-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-070983-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-070996-4 ISSN 2199-6962 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110709834 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950085 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Ari Bergmann, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image: Portrait of Isaac HaLevy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Isaac_halevi_portrait. png, „Isaac halevi portrait“, edited, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ legalcode. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Chapter 1 Y.I. Halevy: The Traditionalist in a Time of Change 1.1 Introduction Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s life exemplifies the multifaceted experiences and challenges of eastern and central European Orthodoxy and traditionalism in the nineteenth century.1 Born into a prominent traditional rabbinic family, Halevy took up the family’s mantle to become a noted rabbinic scholar and author early in life. -

Judah David Eisenstein and the First Hebrew Encyclopedia

1 Abstract When an American Jew Produced: Judah David Eisenstein and the First Hebrew Encyclopedia Between 1907 and 1913, Judah David Eisenstein (1854–1956), an amateur scholar and entrepreneurial immigrant to New York City, produced the first modern Hebrew encyclopedia, Ozar Yisrael. The Ozar was in part a traditionalist response to Otsar Hayahdut: Hoveret l’dugma, a sample volume of an encyclopedia created by Asher Ginzberg (Ahad Ha’am)’s circle of cultural nationalists. However, Eisenstein was keen for his encyclopedia to have a veneer of objective and academic respectability. To achieve this, he assembled a global cohort of contributors who transcended religious and ideological boundaries, even as he retained firm editorial control. Through the story of the Ozar Yisrael, this dissertation highlights the role of America as an exporter of Jewish culture, raises questions about the borders between Haskalah and cultural nationalism, and reveals variety among Orthodox thinkers active in Jewish culture in America at the turn of the twentieth century. When an American Jew Produced: Judah David Eisenstein and the First Hebrew Encyclopedia by Asher C. Oser Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Jewish History Bernard Revel Graduate School Yeshiva University August 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 by Asher C. Oser iii The Committee for this doctoral dissertation consists of Prof. Jeffrey S. Gurock, PhD, Chairperson, Yeshiva University Prof. Joshua Karlip, PhD, Yeshiva University Prof. David Berger, PhD, Yeshiva University iv Acknowledgments This is a ledger marking debts owed and not a place to discharge them. Some debts are impossible to repay, and most are the result of earlier debts, making it difficult to know where to begin. -

Yeshivat Eretz Hatzvi Haggadah 5780/2020

YESHIVAT ERETZ HATZVI HAGGADAH 5780/2020 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Introduction……………………………………………….……………..2 Begin at the Beginning, Rav Susman………………………....3 Ha Lachma Anya – Leib Malina……………………………..…..5 Ma Nishtana – Oliver Bass……………………………………..….6 Avadim Hayinu – Raffi Burnstein……………………………….7 Ma’aseh b’Rabbi Eliezer – Isaac Kauffman………………...8 Arba Banim – Sam Brummer………………………………….....9 V’Hi She’amda – Eytan Labe…………………………………..…10 V’Hi She’amda – Raphael Donath (Hebrew)……..…...…11 The Ten Plagues – Ayal Doctors……………………..……...…12 The Ten Plagues – Hezki Strassman……………….…...……14 Dayenu – Joey Tropper……………………………………..……..15 Rabban Gamliel Haya Omer – Joseph Edelheit….……..16 Brocha of Ga’al Yisrael – Gav Labe…………………….……..17 Afikoman – Jared Levy……………………………………..........19 Hallel and Hallel HaGadol – Gadi Sachs…………………...20 Nirtza – Sam Kaszirer……………………………………………...23 Chad Gadya – Jonah Weiniger…………………………………24 2 ֶשׁ ְבּ ָכל דּוֹר ָודוֹר עוֹ ְמ ִדים ָע ֵלינוּ ְל ַכלּוֹ ֵתנו ְו ַה ָקּדוֹשׁ ָבּרוּ הוּא ַמ ִצּי ֵלנוּ ִמ ָיּ ָד ם “In each and every generation, they come upon us to destroy us, and HaShem saves us from their hands.” (From the Passover Haggadah) We recite the VeHi SheAmda paragraph in the Haggadah annually, commemorating the attempt by others to destroy the Jewish people. Just like in the time of the Exodus from Egyptian bondage and Pharaoh’s evil outstretched arm, we trust that HaShem will save the Jewish people. This salvation is a national promise. On an individual level, we know some suffer, and their suffering is beyond our comprehension. But the Haggadah promises that as a collective, the Jewish people will survive. This year many Jews in Israel and the Diaspora face, with the rest of humanity, a terror which lacks intent but is devastating none the less. -

Malbim on Job Chapter 42: the Happy Ending

MALBIM ON JOB CHAPTER 42: THE HAPPY ENDING GERALD ARANOFF INTRODUCTION Rabbi Meir Leibush (1809–1879), known as Malbim, was a Romanian and Polish rabbi, preacher, and Hebraist who wrote a commentary on the Penta- teuch and Sifra (Warsaw, 1874-80), and a commentary on the Prophets and Writings (Warsaw, 1874). Malbim is popular and highly respected among Orthodox Jewish scholars and may well be the leading relatively modern Jewish commentator on Job, as well on all the books of the Tanakh. In this paper I present Malbim's analysis of Job chapter 42. I discuss other chapters of Job and midrashic sources to explain Malbim's analysis of this chapter. What may surprise and please lovers of the Bible is that Malbim gives a truly happy ending in Job chapter 42, claiming that Job's seven sons and three daughters didn't die, but were only captured and held by Satan and then re- leased unharmed! This makes the Book of Job far more pleasant to read – it becomes a consoling and heartening book since no one dies before their time. According to Malbim, Job is not a tragic story of a man who lost his ten chil- dren and then had another ten. Such a story is frightening and sad. Based on Malbim's understanding of the end of Job, there is only joy. This supports the view that Moses wrote the Book of Job and taught it to the Israelites in Egypt. Malbim mentions in the forward to his commentary on Job, "Our sag- es say that Moses, may he rest in peace, wrote the Book of Job. -

Appendix: a Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources

Appendix: A Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources Although, in an historical sense, the Hebrew scriptures are the foundation of Judaism, we have to turn elsewhere for the documents that have defined Judaism as a living religion in the two millennia since Bible times. One of the main creative periods of post-biblical Judaism was that of the rabbis, or sages (hakhamim), of the six centuries preceding the closure of the Babylonian Talmud in about 600 CE. These rabbis (tannaim in the period of the Mishnah, followed by amoraim and then seboraim), laid the foundations of subsequent mainstream ('rabbinic') Judaism, and later in the first millennium that followers became known as 'rabbanites', to distinguish them from the Karaites, who rejected their tradition of inter pretation in favour of a more 'literal' reading of the Bible. In the notes that follow I offer the English reader some guidance to the extensive literature of the rabbis, noting also some of the modern critical editions of the Hebrew (and Aramaic) texts. Following that, I indicate the main sources (few available in English) in which rabbinic thought was and is being developed. This should at least enable readers to get their bearings in relation to the rabbinic literature discussed and cited in this book. Talmud For general introductions to this literature see Gedaliah Allon, The Jews in their Land in the Talmudic Age, 2 vols (Jerusalem, 1980-4), and E. E. Urbach, The Sages, tr. I. Abrahams (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 1987), as well as the Reference Guide to Adin Steinsaltz's edition of the Babylonian Talmud (see below, under 'English Transla tions').