Yeshivat Eretz Hatzvi Haggadah 5780/2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rabbi Chaim Tabasky Bar-Ilan University November 13-18, 2008

Max and Tessie Zelikovitz Centre for Jewish Studies A Week of Jewish Learning Rabbi Chaim Tabasky Bar-Ilan University November 13-18, 2008 Co-sponsored by the Soloway Jewish Community Centre, Congregation Machzikei Hadas, and Congregation Beit Tikvah. Rabbi Chaim Tabasky teaches Talmud at the Machon HaGavoa L’Torah (Institute of Advanced Torah Studies) at Bar Ilan University. He has taught extensively in Jerusalem Yeshivot both for men and women, especially in programs for English speaking academics: (Yeshivat HaMivtar and Michlelet Bruria – Rabbi Chaim Brovender dean; Yeshivat Darchei Noam; Michlala l’Banot in Bayit v’Gan; Nishmat: MaTan) Three Evenings of Torah Two-part series: Shabbaton with Study: An Encounter Rabbi Tabasky, with Talmud Study 1. Anger, Spite and Cruelty in Family Friday, Nov. 14 and Saturday, Nov. 15, Relations; Biblical teachings and 1) Part One: Sunday, Nov 16, 12:30-3:30 Congregation Machzikei Hadas. Modern Applications, Thurs., Nov 13, pm, Soloway Jewish Community Centre 7:00-9:00 pm, Carleton University, Tory 1. Shabbat Dinner: Youth after Trauma: Building Room 446. The workshop will focus on textual study of a New Religious Manifestations among 2. Two Torah-based Analyses of the section of Talmud -- in order to learn about Israeli Youth after Gaza and the Interaction between Divine structure, method, Talmudic logic and a Second Lebanon War, Fri., Nov. 14 Providence and Free Will in Ethical Halachic idea. Even those with little or no 2. Shabbat morning: Drash on the Decisions background will be encouraged to engage Parsha, Sat., Nov. 15 a) The Role of God in the Murder of the Talmudic texts and the sages in a 3. -

Rav Soloveitchik on the Jewish Family

MORE CHOICES F A L L 5 7 7 9 / 2 0 1 8 - 1 9 CONTENTS HOW TO REGISTER .................................................................................................................................... 2 EMUNAH: • Section I: Modern Jewish Thought .............................................................................. 4 • Section II: Classical Jewish Thought ............................................................................. 7 • Section III: Personal Growth ...................................................................................... 11 HISTORY AND SOCIETY ............................................................................................................................ 21 SHANA BET LEADERSHIP PROGRAM .......................................................................................................... 24 TANACH: • Section I: Topics in Tanach ......................................................................................... 25 • Section II: Parshat Ha-Shavu’a ................................................................................... 29 • Section III: Chumash ................................................................................................... 35 • Section IV: Sefarim in Nach ........................................................................................ 37 HALACHAH: • Section I: Contemporary Halachah ............................................................................ 41 • Section II: Classic Topics in Halachah ........................................................................ -

Liste Des Établissements Reconnus Mise À Jour: Janvier 2017

La Première financière du savoir ‐ Liste des établissements reconnus Mise à jour: janvier 2017 Pour rechercher cette liste d'établissements reconnus, utilisez <CTRL> F et saisissez une partie ou la totalité du nom de l'école. Ou cliquez sur la lettre pour naviguer dans cette liste: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 1ST NATIONS TECH INST-LOYALIST COLL Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory ON Canada 5TH WHEEL TRAINING INSTITUTE, NEW LISKEARD NEW LISKEARD ON Canada A1 GLOBAL COLLEGE OF HEALTH BUSINESS AND TECHNOLOG MISSISSAUGA ON Canada AALBORG UNIVERSITETSCENTER Aalborg Foreign Prov Denmark AARHUS UNIV. Aarhus C Foreign Prov Denmark AB SHETTY MEMORIAL INSTITUTE OF DENTAL SCIENCE KARNATAKA Foreign Prov India ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY Aberystwyth Unknown Unknown ABILENE CHRISTIAN UNIV. Abilene Texas United States ABMT COLLEGE OF CANADA BRAMPTON ON Canada ABRAHAM BALDWIN AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE Tifton Georgia United States ABS Machining Inc. Mississauga ON Canada ACADEMIE CENTENNALE, CEGEP MONTRÉAL QC Canada ACADEMIE CHARPENTIER PARIS Paris Foreign Prov France ACADEMIE CONCEPT COIFFURE BEAUTE Repentigny QC Canada ACADEMIE D'AMIENS Amiens Foreign Prov France ACADEMIE DE COIFFURE RENEE DUVAL Longueuil QC Canada ACADEMIE DE ENTREPRENEURSHIP QUEBECOIS St Hubert QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASS. ET D ORTOTHERAPIE Gatineau (Hull Sector) QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE ET D ORTHOTHERAPIE GATINEAU QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE DRUMMONDVILLE Drummondville QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE LANAUDIERE Terrebonne QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE QUEBEC Quebec QC Canada ACADEMIE DE SECURITE PROFESSIONNELLE INC LONGUEUIL QC Canada La Première financière du savoir ‐ Liste des établissements reconnus Mise à jour: janvier 2017 Pour rechercher cette liste d'établissements reconnus, utilisez <CTRL> F et saisissez une partie ou la totalité du nom de l'école. -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

Yeshivat Eretz Hatzvi

Insights into Rosh Hashanah & Yom Kippur by the faculty of Yeshivat Eretz HaTzvi 1 Quote on the cover from Piyut for Yom Kippur by Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra. © 2010 Yeshivat Eretz HaTzvi All rights reserved 2 3 "ר ח אל ול תש"ס êúå ë ÀìÇî à ÅNÈpÄú Éåáe . íÉéÈàÀå à ÈøÉåð àeä é Äk . íÉåi Çä ú ÇMËãÀ÷ ó Æ÷Éú äÆpÇúÀðe The "Yomim Noraim" approach us in all their splendor, power, and awe. In the yeshiva, the new year takes on a special meaning as the students and rabbanim prepare not only for the days of awe, but also for the entire learning calendar. The summer has passed and now is time to begin a new cycle of Torah learning. There is no better way to approach learning than hearing the wake up call of the shofar blast in Ellul and greeting the world and Yerushalayim refreshed and energized. íéìùå øé Äî äÈåÉäÀé ø ÇáÀãe ä ÈøÉåú à ÅöÅz ïÉåi ÄvÄî é Äk This summer, in addition to preparing for the arrival of our new talmidim , the faculty pulled its resources to send to all our friends and family divrei Torah from our Beit Midrash. With great pleasure we bring you Torah from Eretz HaTzvi. Eretz HaTzvi has two connotations for us here in the yeshiva – Eretz Yisrael and Yeshivat Eretz HaTzvi and these Torah insights share both meanings. In this modest volume, you will find different styles and approaches to the meaning of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur representing many of the members of the yeshiva faculty. -

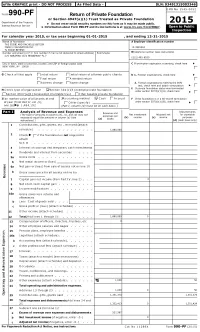

2015 Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS I As Filed Data - I DLN: 93491315003346 OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2015 Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service ► ► Information about Form 990- PF and its instructions is at www. irs.gov /form99Opf . • • ' For calendar year 2015 , or tax year beginning 01-01 - 2015 , and ending 12-31-2015 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE EDDIE AND RACHELLE BETESH FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 13-3981963 EDDIE BETESH Number and street ( or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) BTelephone number (see instructions) C/O SARAMAX-1372 BROADWAY-FL 7 (212) 481-8550 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ► NEW YORK, NY 10018 P G Check all that apply [Initial return [Initial return former public charity of a D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► F-Final return F-A mended return P F-Address change F-Name change 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach computation ► E If private foundation status was terminated H Check type of organization [Section 501( c)(3) exempt private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► F Section 4947( a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation IFair market value of all assets at end ] Accounting method [Cash F-Accrual F If the foundation -

Vertientes Del Judaismo #3

CLASES DE JUDAISMO VERTIENTES DEL JUDAISMO #3 Por: Eliyahu BaYonah Director Shalom Haverim Org New York Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • La Ortodoxia moderna comprende un espectro bastante amplio de movimientos, cada extracción toma varias filosofías aunque relacionados distintamente, que en alguna combinación han proporcionado la base para todas las variaciones del movimiento de hoy en día. • En general, la ortodoxia moderna sostiene que la ley judía es normativa y vinculante, y concede al mismo tiempo un valor positivo para la interacción con la sociedad contemporánea. Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • En este punto de vista, el judaísmo ortodoxo puede "ser enriquecido" por su intersección con la modernidad. • Además, "la sociedad moderna crea oportunidades para ser ciudadanos productivos que participan en la obra divina de la transformación del mundo en beneficio de la humanidad". • Al mismo tiempo, con el fin de preservar la integridad de la Halajá, cualquier área de “fuerte inconsistencia y conflicto" entre la Torá y la cultura moderna debe ser evitada. La ortodoxia moderna, además, asigna un papel central al "Pueblo de Israel " Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • La ortodoxia moderna, como una corriente del judaísmo ortodoxo representado por instituciones como el Consejo Nacional para la Juventud Israel, en Estados Unidos, es pro-sionista y por lo tanto da un estatus nacional, así como religioso, de mucha importancia en el Estado de Israel, y sus afiliados que son, por lo general, sionistas en la orientación. • También practica la implicación con Judíos no ortodoxos que se extiende más allá de "extensión (kiruv)" a las relaciones institucionales y la cooperación continua, visto como Torá Umaddá. -

New Contradictions Between the Oral Law and the Written Torah 222

5/7/2019 222 New Contradictions between the Oral Torah and the Written Torah - iGod.co.il Science and faith main New Contradictions Between The Oral Law And The Written Torah 222 Contradictions in the Oral Law Talmud Mishneh Halacha 1/68 /מדע-אמונה/-101סתירות-מביכות-בין-התורה-שבעל-פה-לתורה/https://igod.co.il 5/7/2019 222 New Contradictions between the Oral Torah and the Written Torah - iGod.co.il You may be surprised to hear this - but the concept of "Oral Law" does not appear anywhere in the Bible! In truth, such a "Oral Law" is not mentioned at all by any of the prophets, kings, or writers in the entire Bible. Nevertheless, the Rabbis believe that Moses was given the Oral Torah at Sinai, which gives them the power, authority and control over the people of Israel. For example, Rabbi Shlomo Ben Eliyahu writes, "All the interpretations we interpret were given to Moses at Sinai." They believe that the Oral Torah is "the words of the living God". Therefore, we should expect that there will be no contradictions between the written Torah and the Oral Torah, if such was truly given by God. But there are indeed thousands of contradictions between the Talmud ("the Oral Law") and the Bible (Torah Nevi'im Ketuvim). According to this, it is not possible that Rabbinic law is from God. The following is a shortened list of 222 contradictions that have been resurrected from the depths of the ocean of Rabbinic literature. (In addition - see a list of very .( embarrassing contradictions between the Talmud and science . -

Kehilath Jeshurun Bulletin

CELEBRATING OUR 136TH YEAR OF SERVICE KEHILATH JESHURUN BULLETIN Volume LXXVI, Number 4 July 10, 2007 24 Tammuz 5767 KJ AND RAMAZ PLAN MAJOR BUILDING PROJECT LOWER SCHOOL AND SYNAGOGUE HOUSE TO BE ENTIRELY REBUILT In an historic meeting of the School structure with 18 floors of Center which need a different kind of Boards of Trustees of the Congregation condominium apartments above. These structure to provide the proper education and Ramaz - a first in the history of this apartments, which will be sold by a for children in the 21st Century. The new community - and an open session for the developer who will build the building, will building will provide, among other things, entire community, a major plan was defray close to half the cost of the new the following: presented which will affect the future of community structure. FOR THE CONGREGATION this community for the next 50 years and The current Synagogue House - 1.A greatly expanded Chapel and a new beyond. The plan calls for the demolition as opposed to the main synagogue building Beit Midrash. of the Synagogue House and Ramaz which will remain intact - is over 80-years- 2.An enlarged social hall. Lower School building at 125 East 85th old. It no longer serves the needs of a 3.A significantly enlarged auditorium for Street and its replacement by a 10-story vastly expanded congregation or the meetings and both Synagogue House and Ramaz Lower Ramaz Lower School and Early Childhood (continued on page 7) 99 SENIORS ARE GRADUATED FROM THE JOSEPH H. LOOKSTEIN UPPER SCHOOL OF RAMAZ 57 TO SPEND NEXT YEAR IN ISRAEL SENIORS AND LOWER CLASSMEN WIN MANY ACADEMIC HONORS Once again it has been an amazing year for the students in Ramaz! The seniors also earned a wonderful record of college acceptances. -

JCF-2018-Annual-Report.Pdf

JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Since 2000, Jewish Communal Fund’s generous Fundholders have made nearly $5 Billion in grants to charities in all sectors, including: + GRANTS 300,000 to Jewish organizations in the United States, totaling nearly $2 Billion + GRANTS 100,000 to Israeli and international charities, totaling $664 Million + GRANTS 200,000 to general charities in the United States, totaling $2.4 Billion CONTENTS 1 Letter from President and CEO 2 JCF Reinvests in the Jewish Community 3 JCF Adds Social Impact Investments in Every Asset Class 4 Investments 5–23 Financial Statements 24–37 Grants 38–55 Funds 56 Trustees/Staff 2018 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2018 very year, we are humbled by the enormous generosity of JCF’s Fundholders. FY 2018 was no exception—our Fundholders recommended a staggering 58,000 grants totaling $435 million to charities in every sector. It is our privilege to facilitate your grant- Emaking, and we are pleased to report a record-breaking year of growth and service to the Jewish community. By choosing JCF to facilitate your charitable giving, you further enable us to make an annual $2 million unrestricted grant to UJA-Federation of New York, to support local Jewish programs and initiatives. In addition, JCF’s endowment, the Special Gifts Fund, continues to change lives for the better, granting out more than $17 million since 1999. Your grants and ours combine to create a double bottom line. Grants from the Special Gifts Fund are the way that our JCF network collectively expresses its support for the larger Jewish community, and this sets JCF apart from all other donor advised funds. -

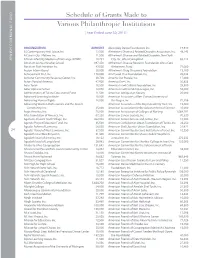

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

![1] Rabbi Malbim](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5431/1-rabbi-malbim-2095431.webp)

1] Rabbi Malbim

MAHARSHA Rabbi Shmuel Edelles Born 1555, / Yahrzeit date: 5th of Kislev 1631 The first interesting point to mention about this great personality is that his family appellative is feminine; it is the name of his mother in law. How so? It is since she (as a rich widow) supported financially the upkeepof Rabbi Shmuel’s yeshiva, for over 20 years. Only at her decease, and the aid was halted, did that yeshiva cease to exist. Then it was that he received a rabbinical position. In order to show due regard and gratitude, he constantly signed his name by adding thereto her name (“Adelle”). It is also true that his wife was a descendant of the world famous Maharal. (Encyclopedia Otzar Israel, ed. by D. Eisenstein. Some of the forthcoming material in our article we culled from that work). This great rabbi wrote one of the most important commentaries to be able thereby to understand the abstruse Talmudic dialectics. The gaon “Hazzon Ish” advises each and every Yeshiva student to make full use of this Maharsha comentary (“Letters”, beginning of article one; end of article 20) and to paraphrase his words: “It is a boon grant for Kllal Israel, to aid all subsequent generations in the task of understanding the Torah properly”. Maharsha was a genius in logical explanations, and detested false Pilpul, which was rampant in his period (and was also despised by the Sha’loh, Masechet Shevuot, and so too by the Maharal, in his commentary to Avot, pp. 305-306). He charges that false “Hillukim” deter a person from the truth, since each disputant is only vehemently interested in “winning the debate” and is negatively impassioned to disprove the dissenting opinion (Commentary to Bava Metzia 85a “Delishtakach”).