View When Contacted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747 University Of Namibia NEPAL 001252 Tribhuvan University NETHERLANDS 004215 A T College 002311 Acad Voor Gezondheidszorg 004215 Atc 004510 Baarns Lyceum 000109 Catholic University Tilburg 000107 Catholic University, Nijmegan 000101 Delft University Of Technology 002272 Dordrecht Polytech 004266 Eindhoven Sec Schl 000102 Eindhoven Univ Technology 002452 Enschede College 000108 Erasmus Univ Rotterdam 000100 Free Univ Amsterdam 002984 Haarlem Business School 000112 Institute Of Social Studies 000113 Int Inst Aero Survey& Space Sc 004751 Katholieke Scholengemeenschap 002461 Netherlands School Of Business 000114 Philips Int Inst Tech Studies 046294 Rijksuniversiteit Leiden 000115 Royal Tropical Institute 004152 Schola Europaea Bergensis 000104 State Univ Groningen 000105 State Univ Leiden 000106 State Univ Limburg 000110 State Univ Utrecht 002430 State University Of Utrecht 004276 Stedelijk Gymnasium 002543 Technische Hogeschool Rijswijk 003615 The British Sch /netherlands 002452 Twentse Academie Voor Fysiothe 000099 Univ Amsterdam 000103 University Of Twente 002430 University Of Utrecht 000111 Wageningen Agricultural Univ 002242 Wageningen Agricultural Univ NETHERLANDS ANTILLES 002476 Univ Netherlands Antilles NEW ZEALAND 000758 Lincoln Col Canterbury 000759 Massey Univ Palmerston 000756 The University Of Auckland 000757 Univ Canterbury 000760 Univ Otago 000762 Univ Waikato International Schools 000761 Victoria Univ Wellington NICARAGUA 000210 Univ Centroamericana 000209 Univ Na Auto Nicaragua -

Preservation of the Canaanite Creation Culture in Ife1

Preservation of the Canaanite Creation Culture in Ife1 Dierk Lange For Africanists, the idea that cultures from the ancient Near East have influenced African societies in the past in such a way that their basic fea- tures are still recognizable in the present suggests stagnation and regres- sion. Further, they associate the supposed spread of cultural patterns with wild speculations on diffusion: How can Canaan, which is often con- sidered to be the culture of the Near East which preceeded Israel, have had any influence on Africa? They overlook the fact that the Phoenicians were none other than the Canaanites and that as a result of their expan- sion the Canaanite culture stretched to North Africa and to the coast of the Atlantic. In the North African hinterland it reached at least as far as the Fezzan, the most important group of oases in the Central Sahara.2 Scholars of Africa pay insufficient attention to the fact that the central Sahara, similarly to the Mediterranean, with its infertile yet easily cross- able plains and its often high ground water level, was more a benefit to communication than a hindrance.3 Finally, they misjudge the significance of the diffusion process worldwide, which has been emphasized by world historians like McNeill4: If Europe and Asia owe essential developmental impulses to ancient near eastern influences, why should not Africa as well? My current project, however, is not an attempt to show the integration of African peoples into ancient world history, but rather to explore the ne- 1 The following study owes its main thrust to discussions with my friend and colleague Prof. -

AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Open Educational Resources Borough of Manhattan Community College 2021 AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture Remi Alapo CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bm_oers/29 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Presented as part of the discussion on West Africa about the instructor’s Heritage in the AFN 121 course History of African Civilizations on April 20, 2021. Yoruba Tradition and Culture Prof. Remi Alapo Department of Ethnic and Race Studies Borough of Manhattan Community College [BMCC]. Questions / Comments: [email protected] AFN 121 - History of African Civilizations (Same as HIS 121) Description This course examines African "civilizations" from early antiquity to the decline of the West African Empire of Songhay. Through readings, lectures, discussions and videos, students will be introduced to the major themes and patterns that characterize the various African settlements, states, and empires of antiquity to the close of the seventeenth century. The course explores the wide range of social and cultural as well as technological and economic change in Africa, and interweaves African agricultural, social, political, cultural, technological, and economic history in relation to developments in the rest of the world, in addition to analyzing factors that influenced daily life such as the lens of ecology, food production, disease, social organization and relationships, culture and spiritual practice. -

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: a Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: A Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi by Akinyemi Yetunde Blessing [email protected] Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria Abstract In this paper an attempt is made to examine the mythic narratives and ritual performances in olojo festival and to discuss the traditional involvement of the Ooni of Ife during the festivals, making reference to the late Ọợni Adesoji Adėrėmí. This paper also investigates the implication of local, national and international politics on the traditional festival in Ile-Ife. The importance of the study arrives as a result of the significance of the Ile-Ife amidst the Yoruba towns. More so, festivals have cultural significance that makes some unique turning point in the history of most Yoruba society. Ǫlợjợ festival serves as the worship of deities and a bridge between the society and the spiritual world. It is also a day to celebrate the re-enactment of time. Ǫlợjợ festival demands the full participation of the reigning Ọợni of Ife. The result of the field investigation revealed that the myth of Ǫlợjợ festival remains, but several changes have crept into the ritual process and performances during the reign of the late Adesoji Adėrėmí. The changes vary from the ritual time, space, actions and amidst the ritual specialists. It is found out that some factors which influence these changes include religious contestation, ritual modernization, economics and political change not at the neglect of the king’s involvement in the local, national and international politics which has given space for questioning the Yoruba kingship institution. -

When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire Under Historial Review

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rimcis.hipatiapress.com When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo1 1) Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission, Nigeria Date of publication: November 30th, 2014 Edition period: November 2014 – March 2015 To cite this article: Ojo, M.O.D. (2014). When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 248-267. doi: 10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). RIMCIS – International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 3 No.3 November 2014 pp. 248-267 When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historical Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission Abstract Using historical events research approach and qualitative key informant interview, this study examined how religion failed to stop political crisis that happened in the old Western region of Nigeria. Ikire, in the present Osun State of Nigeria was used as a case study. The study investigated the incidences of killing, arson and exile that characterized the crisis in the town which served as the case study. It argued that the two prominent political figures which started the crisis failed to apply the religious doctrines of love, peace and brotherhood which would have solved the crisis before it spread to all parts of the Old Western Region of Nigeria and the entire nation. -

Title the Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 Author(S

Title The Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 ADESOJI, Abimbola O.; HASSAN, Taofeek O.; Author(s) AROGUNDADE, Nurudeen O. Citation African Study Monographs (2017), 38(3): 147-171 Issue Date 2017-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/227071 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 38 (3): 147–171, September 2017 147 THE MINORITY QUESTION IN IFE POLITICS, 1946–2014 Abimbola O. ADESOJI, Taofeek O. HASSAN, Nurudeen O. AROGUNDADE Department of History, Obafemi Awolowo University ABSTRACT The minority problem has been a major issue of interest at both the micro and national levels. Aside from the acclaimed Yoruba homogeneity and the notion of Ile-Ife as the cradle of Yoruba civilization, relationships between Ife indigenes and other communities in Ife Division (now in Osun State, Nigeria) have generated issues due to, and influenced by, politi- cal representation. Where allegations of marginalization have not been leveled, accommoda- tion has been based on extraneous considerations, similar to the ways in which outright exclu- sion and/or extermination have been put forward. Not only have suspicion, feelings of outright rejection, and subtle antagonism characterized majority–minority relations in Ife Division/ Administrative Zone, they have also produced political-cum-administrative and territorial ad- justments. As a microcosm of the Nigerian state, whose major challenge since attaining politi- cal independence has been the harmonization of interests among the various ethnic groups in the country, the Ife situation presents a peculiar example of the myths and realities of majority domination and minority resistance/response, or even a supposed minority attempt at domina- tion. -

The House of Oduduwa: an Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa

The House of Oduduwa: An Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa by Andrew W. Gurstelle A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Carla M. Sinopoli, Chair Professor Joyce Marcus Professor Raymond A. Silverman Professor Henry T. Wright © Andrew W. Gurstelle 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I must first and foremost acknowledge the people of the Savè hills that contributed their time, knowledge, and energies. Completing this dissertation would not have been possible without their support. In particular, I wish to thank Ọba Adétùtú Onishabe, Oyedekpo II Ọla- Amùṣù, and the many balè,̣ balé, and balọdè ̣that welcomed us to their communities and facilitated our research. I also thank the many land owners that allowed us access to archaeological sites, and the farmers, herders, hunters, fishers, traders, and historians that spoke with us and answered our questions about the Savè hills landscape and the past. This dissertion was truly an effort of the entire community. It is difficult to express the depth of my gratitude for my Béninese collaborators. Simon Agani was with me every step of the way. His passion for Shabe history inspired me, and I am happy to have provided the research support for him to finish his research. Nestor Labiyi provided support during crucial periods of excavation. As with Simon, I am very happy that our research interests complemented and reinforced one another’s. Working with Travis Williams provided a fresh perspective on field methods and strategies when it was needed most. -

The Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics - An Open Access International Journal Vol.1 2013 The Literary Artist as a Mediator: the Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry Ade Adejumo (Ph.D) Department of General Studies, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology P.M.B. 4000, Ogbomoso,Oyo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper contends that there exists a paradoxical relationship between violence and conflictual situations on one hand, and the literary art on the other. While conflictual violence exerts tremendous strains on human relations, literary artists have often had their creative sensibilities fired by such conflicts. The above accounts for the emergence of the war-sired creative enterprise collectively referred to as war literature. These writers have used their art either as mere chronicles of the unfolding drama of blood and death or as interventionist art to preach peace and restoration of human values. Using the Nigerian experience, this paper does an examination of select corpus of poetry, which emanated from the Nigerian civil war experience. It isolates the messages of peace, which went a long way in not only pointing out the evils occasioned by war and conflict but also in suturing the broken ties of humanity while the war lasted. As our societies are becoming increasingly conflictual, our literary endeavours should also assume more social responsibilities in terms of conflict mitigation, prevention and promotion of global peace. This paper therefore envisions a new literary movement i.e. -

Title the Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 Author

Title The Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 ADESOJI, Abimbola O.; HASSAN, Taofeek O.; Author(s) AROGUNDADE, Nurudeen O. Citation African Study Monographs (2017), 38(3): 147-171 Issue Date 2017-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/227071 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 38 (3): 147–171, September 2017 147 THE MINORITY QUESTION IN IFE POLITICS, 1946–2014 Abimbola O. ADESOJI, Taofeek O. HASSAN, Nurudeen O. AROGUNDADE Department of History, Obafemi Awolowo University ABSTRACT The minority problem has been a major issue of interest at both the micro and national levels. Aside from the acclaimed Yoruba homogeneity and the notion of Ile-Ife as the cradle of Yoruba civilization, relationships between Ife indigenes and other communities in Ife Division (now in Osun State, Nigeria) have generated issues due to, and influenced by, politi- cal representation. Where allegations of marginalization have not been leveled, accommoda- tion has been based on extraneous considerations, similar to the ways in which outright exclu- sion and/or extermination have been put forward. Not only have suspicion, feelings of outright rejection, and subtle antagonism characterized majority–minority relations in Ife Division/ Administrative Zone, they have also produced political-cum-administrative and territorial ad- justments. As a microcosm of the Nigerian state, whose major challenge since attaining politi- cal independence has been the harmonization of interests among the various ethnic groups in the country, the Ife situation presents a peculiar example of the myths and realities of majority domination and minority resistance/response, or even a supposed minority attempt at domina- tion. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

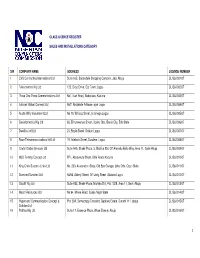

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics

NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS VOLUME 4 NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY, 2014 CONTENTS PAGE Onu, J.O., J.N. Nmadu and L. Tanko: Determinants of Awareness of Credit Procurement Procedures and Farmers Income In Minna Metropolis, Nigeria 1-11 Adeolu B. Ayanwale and Christianah A. Amusan: Gender Analysis of Rice Production Efficiency in Osun State: Implication for the Transformation Agenda 12-24 Obayelu A. E. and Obayelu, O. A.: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Analysis of the Nigeria Agricultural Transformation Agenda 25-43 Kareem, R.O, Ayinde, I.A, Bakare H.A, and Bashir, N.O: Determinants of Aggregate Agricultural Supply Response in Nigeria (1960-2010) 44-57 Obayelu, A.E., Arowolo, A.O., Ibrahim S.B. and Croffie A.Q: Economics of Fresh Tomato Marketing in Kosofe Local Government Area Of Lagos State, Nigeria 58-67 Ayinde, O. E, Adewumi, M.O., Nmadu, J. N., Olatunji, G. B and Egbugo K.: Review of Marketing Board Policy: Comparative Analysis Cocoa of Pricing Eras In Nigeria 68-79 Ayinde, I. A., Kareem, R. O. and Lasisi, K.: Economic Assessment of the Effect of the Nigerian Technology Incubation Programme on Agro-Allied Small and Medium Scale Enterprises 80-92 Authors Guide: Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics 93-94 Published by the Nigerian Association of Agricultural Economists Editorial Board Editorial Policy Editor-in-Chief Prof. Foluso Okunmadewa, The Journal serves mainly as a medium for Sector Leader, Human Development the publication of scientific research outputs World Bank Africa Region in all fields of Agricultural Economics and Country Office, Abuja, Nigeria allied disciplines. It also publishes review articles and theoretical papers (research Assistant Editors-in-Chief papers, review articles) concerned with Prof Ben Hammed, agricultural development in the tropical Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria world and Nigeria in particular.