In Praise of Switzerland: Being the Alps in Prose and Verse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cíl Všech Horolezccíl Všech Horolezců Na Vrchol Mont Blanc Vede Více Cest

Grandes Jorasses Dent du Géant Aiguille du Midi Mont Blanc du Tacul Mont Maudit Mont Blanc Dôme du Goûter Aiguilles de Bionnassay 4208 m 4013 m 3842 m 4248 m 4465 m 4810 m 4304 m 4052 m Refuge des Refuge des Grands Mulets Refuge du Goûter Refuge de Tête Rousse Cosmiques 3051 m 3835 m 3167 m 3613 m Arête du Dôme La Jonction Plan de l’aiguille ! Uvědomte si nebezpečí Chamonix Nepleťte si obtížnost s nebezpečím. Nejrušnější cesty na Mont Blanc nejsou odborně řečeno nijak Plan de zvlášť náročné. Avšak vyskytují se na nich všechna nebezpečí spojená s tímto prostředím. Dosažení vrcholu Mont Blanc l'Aiguille 7 cest na vrchol Alp Pro snížení rizika začněte nejprve s identifikací nebezpečí terénu a monitorováním aktuálního stavu a možností členů vaší skupiny. Cíl všech horolezcCíl všech horolezců Na vrchol Mont Blanc vede více cest. St-Gervais- 3 les-Bains léphérique Té Nadmořská výška Vyzkoušet některou z méně klasických cest může být zábavné, zvláště v ruš- Pro nás horolezce, kteří kolikrát cestujeme tisíce kilometrů, abychom vylezli na vrchol nějším období. Techničtější pasáže vyžadují velké zkušenosti. Kvůli obtížnosti a Čím výše stoupáte, tím méně je kyslíku. les Houches AHN (akutní horská nemoc) je neustálou hrozbou. Bolest hlavy, Mont Blancu, je to něco víc než jen další vrchol v deníčku. Je to sen, někdy i legenda. Historie naší hlavně kvůli riziku expozice. TMB nespavost, dýchavičnost, nechutenství, pocit ucpaného nosu...hlavní příznaky se mohou objevit již v 3 500 m. vášně je vepsána do jeho svahů. Horlivé snažení, nedotčené svahy a elegantní štíty, přátelství na Nedá se dělat nic jiného, než se vrátit zpět. -

The Summits of Modern Man: Mountaineering After the Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013)

Bibliography Peter H. Hansen, The Summits of Modern Man: Mountaineering after the Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013) This bibliography consists of works cited in The Summits of Modern Man along with a few references to citations that were cut during editing. It does not include archival sources, which are cited in the notes. A bibliography of works consulted (printed or archival) would be even longer and more cumbersome. The print and ebook editions of The Summits of Modern Man do not include a bibliography in accordance with Harvard University Press conventions. Instead, this online bibliography provides links to online resources. For books, Worldcat opens the collections of thousands of libraries and Harvard HOLLIS records often provide richer bibliographical detail. For articles, entries include Digital Object Identifiers (doi) or stable links to online editions when available. Some older journals or newspapers have excellent, freely-available online archives (for examples, see Journal de Genève, Gazette de Lausanne, or La Stampa, and Gallica for French newspapers or ANNO for Austrian newspapers). Many publications still require personal or institutional subscriptions to databases such as LexisNexis or Factiva for access to back issues, and those were essential resources. Similarly, many newspapers or books otherwise in the public domain can be found in subscription databases. This bibliography avoids links to such databases except when unavoidable (such as JSTOR or the publishers of many scholarly journals). Where possible, entries include links to full-text in freely-accessible resources such as Europeana, Gallica, Google Books, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, World Digital Library, or similar digital libraries and archives. -

Note on the History of the Innominata Face of Mont Blanc De Courmayeur

1 34 HISTORY OF THE INNOMINATA FACE them difficult but solved the problem by the most exposed, airy and exhilarating ice-climb I ever did. I reckon sixteen essentially different ways to Mont Blanc. I wish I had done them all ! NOTE ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS FIG. 1. This was taken from the inner end of Col Eccles in 1921 during the ascent of Mont Blanc by Eccles' route. Pie Eccles is seen high on the right, and the top of the Aiguille Noite de Peteret just shows over the left flank of the Pie. FIG. 2. This was taken from the lnnominata face in 1919 during a halt at 13.30 on the crest of the branch rib. The skyline shows the Aiguille Blanche de Peteret on the extreme left (a snow cap), with Punta Gugliermina at the right end of what appears to be a level summit ridge but really descends steeply. On the right of the deep gap is the Aiguille Noire de Peteret with the middle section of the Fresney glacier below it. The snow-sprinkled rock mass in the right lower corner is Pie Eccles a bird's eye view. FIG. 3. This was taken at the same time as Fig. 2, with which it joins. Pie Eccles is again seen, in the left lower corner. To the right of it, in the middle of the view, is a n ear part of the branch rib, and above that is seen a bird's view of the Punta lnnominata with the Aiguille Joseph Croux further off to the left. -

Pour Les Guides

VOIE ROYALE POUR LES GUIDES L’histoire de la compagnie des guides de Saint-Gervais Le 8 août 1786 sonne la fin des espérances locales. est étroitement liée à l’exploration du massif du Mont- Michel Paccard et le guide Jacques Balmat Blanc et à la rivalité avec les communes voisines. atteignent le sommet du mont Blanc depuis Fondée en 1864, elle est la deuxième institution de Chamonix. La voie du Goûter va tomber dans guides de haute montagne en France. Avec quelques l’oubli pendant de nombreuses années. Charles singularités qui la distinguent de ses voisines. Durier, qui fut président et secrétaire général du Club alpin français à partir de 1895, écrira : u xviiie siècle, les tentatives « Chamonix et Saint-Gervais sont deux cités d’ascension du mont Blanc rivales, comme autrefois Rome et Albe. Si la pre- font entrer Saint-Gervais mière comptait les cristalliers les plus hardis, la dans l’histoire de l’alpinisme. seconde était fière à bon droit de l’intrépidité de La conquête de la plus haute ses chasseurs de chamois. C’est par le côté de cime des Alpes ne laisse pas Saint-Gervais que l’ascension du Mont-Blanc avait indifférents les habitants du d’abord paru plus près de réussir… Saint-Gervais pays. Ces paysans, conscients crut tenir la victoire, Chamonix l’emporta et Saint- des retombées économiques potentielles de l’alpi- Gervais en conçut un amer chagrin. » Ascension du mont Blanc La première ascension saint-gervolaine du mont ceux de Chamonix. Elle se dote d’un fonctionnement nisme, vont troquer leurs outils agricoles contre le En 1815, le colonel autrichien Franz-Ludwig von par le pyrénéiste et alpiniste Blanc est réalisée par le chef des guides Joseph- moderne reposant sur la « caisse de secours » (un français Henri Brulle, piolet pour accompagner les premiers voyageurs. -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

Zermatt, Switzerland)

Institut für Geologie Media release / 6 June 2018 Water transport to the Earth’s interior: Clues from high-pressure Alpine rocks (Zermatt, Switzerland) Water in the Earth’s interior influences many geological processes. The evolution of our planet and the development of life is tightly linked to the deep water cycle. Rocks from Zermatt (Switzerland) document formation at the ocean floor, followed by subduction to 80 km depth prior their incorporation into the Alpine belt. The detailed investigation of these rocks by researchers from the University of Bern provides evidence how and how much water can be incorporated in minerals at these subduction zone conditions and how water might be transported to even greater depth. The results are published in the journal “Geology”. The shallow water cycle that links atmosphere and hydrosphere is crucial for life on Earth. However, there exists also a deep water cycle in which water is transported over millions of years through the Earth’s interior. Hydrothermal alteration of oceanic crust results in the formation of minerals that incorporate water into the crystal structure. Through plate tectonics and subduction of such oceanic crust, the hydrous minerals are transported to increasingly greater depths. As the rocks are heated up during burial, the hydrous minerals break down at 50-100 km depth and are replaced by anhydrous minerals resulting in the liberation of the stored water. Would it be possible that traces of water are still incorporated into these newly formed minerals? Would this provide a mechanism to transport water to even greater depth and how would this influence the very long term, hundred million years water cycle? To answer these questions, PhD student Elias Kempf and Prof. -

Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants from Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1934 Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants From Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish. Anna Theresa Daigle Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Daigle, Anna Theresa, "Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants From Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish." (1934). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8182. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8182 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOLKLORE AND ETYMOLOGICAL GLOSSARY OF THE VARIANTS FROM STANDARD FRENCH XK JEFFERSON DAVIS PARISH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SHE LOUISIANA STATS UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND MECHANICAL COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES BY ANNA THERESA DAIGLE LAFAYETTE LOUISIANA AUGUST, 1984 UMI Number: EP69917 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI EP69917 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

Ivrea Mantle Wedge, Arc of the Western Alps, and Kinematic Evolution of the Alps–Apennines Orogenic System

Swiss J Geosci DOI 10.1007/s00015-016-0237-0 Ivrea mantle wedge, arc of the Western Alps, and kinematic evolution of the Alps–Apennines orogenic system 1 1 1 2 Stefan M. Schmid • Eduard Kissling • Tobias Diehl • Douwe J. J. van Hinsbergen • Giancarlo Molli3 Received: 6 June 2016 / Accepted: 9 December 2016 Ó Swiss Geological Society 2017 Abstract The construction of five crustal-scale profiles related to the lateral indentation of the Ivrea mantle slice across the Western Alps and the Ivrea mantle wedge towards WNW by some 100–150 km. (4) The final stage of integrates up-to-date geological and geophysical informa- arc formation (25–0 Ma) is associated with orogeny in the tion and reveals important along strike changes in the Apennines leading to oroclinal bending in the southern- overall structure of the crust of the Western Alpine arc. most Western Alps in connection with the 50° counter- Tectonic analysis of the profiles, together with a review of clockwise rotation of the Corsica-Sardinia block and the the existing literature allows for proposing the following Ligurian Alps. Analysis of existing literature data on the multistage evolution of the arc of the Western Alps: (1) Alps–Apennines transition zone reveals that substantial exhumation of the mantle beneath the Ivrea Zone to shal- parts of the Northern Apennines formerly suffered Alpine- low crustal depths during Mesozoic is a prerequisite for the type shortening associated with an E-dipping Alpine sub- formation of a strong Ivrea mantle wedge whose strength duction zone and were backthrusted to the NE during exceeds that of surrounding mostly quartz-bearing units, Apenninic orogeny that commences in the Oligocene. -

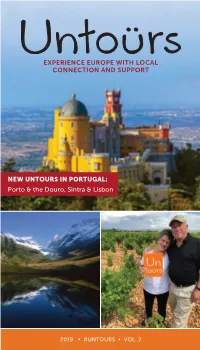

Experience Europe with Local Connection and Support

EXPERIENCE EUROPE WITH LOCAL CONNECTION AND SUPPORT NEW UNTOURS IN PORTUGAL: Porto & the Douro, Sintra & Lisbon 2019 • #UNTOURS • VOL. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS UNTOURS & VENTURES ICELAND PORTUGAL Ventures Cruises ......................................25 NEW, Sintra .....................................................6 SWITZERLAND NEW, Porto ..................................................... 7 Heartland & Oberland ..................... 26-27 SPAIN GERMANY Barcelona ........................................................8 The Rhine ..................................................28 Andalusia .........................................................9 The Castle .................................................29 ITALY Rhine & Danube River Cruises ............. 30 Tuscany ......................................................10 HOLLAND Umbria ....................................................... 11 Leiden ............................................................ 31 Venice ........................................................ 12 AUSTRIA Florence .................................................... 13 Salzburg .....................................................32 Rome..........................................................14 Vienna ........................................................33 Amalfi Coast ............................................. 15 EASTERN EUROPE FRANCE Prague ........................................................34 Provence ...................................................16 Budapest ...................................................35 -

(0)27 966 01 01 Sunnegga Furi Furi Breuil-Cervinia

DE FR EN IT SUNNEGGA-ROTHORN 7 Standard 16 Chamois 28 White Hare 37 Riffelhorn MATTERHORN GLACIER 56 Kuhbodmen 65 Rennstrecke / Skimovie SOMMERSKI / BREUIL-CERVINIA 11 Gran Roc-Pre de Veau 39 Gaspard 9 Baracon PANORAMAKARTE / PLAN PANORAMIQUE / 1 Untere National 8 Obere National 17 Marmotte 29 Kelle 38 Rotenboden PARADISE 57 Aroleid 66 Theodulsee THEODULGLETSCHER 2 Cretaz 12 Muro Europa 46 Bontadini 2 10 Du Col PANORAMIC MAP / MAPPA PANORAMICA. 2 Ried 9 Tufteren 18 Arbzug 30 Mittelritz 39 Riffelalp 49 Bielti 58 Hermetji 67 Garten Buckelpiste 80 Testa Grigia 3 Plan Torrette-Pre de Veau 13 Ventina-Cieloalto 47 Fornet 2 11 Gran Sometta 2a Riedweg (Quartier- 10 Paradise 19 Fluhalp 31 Platte 40 Riffelboden 50 Blatten 59 Tiefbach 68 Tumigu 81 Führerpiste 3.0 Pre de Veau-Pirovano 14 Baby Cretaz 59 Pista Nera del Cervino 12 Gran Lago strasse, keine Skipiste) 11 Rotweng 32 Grieschumme 41 Landtunnel 51 Weisse Perle 60 Momatt 69 Matterhorn 82 Mittelpiste 3.00 Pirovano-Cervinia 16 Cieloalto-Cervinia 60 Snowpark Cretaz 14 Tunnel 2017/2018 3 Howette 12 Schneehuhn GORNERGRAT 33 Triftji 42 Schweigmatten 52 Stafelalp 61 Skiweg 70 Schusspiste 83 Plateau Rosa 3bis Falliniere 21 Cieloalto 1 62 Gran Roc 15 E. Noussan 4 Brunnjeschbord 13 Downhill 25 Berter 34 Stockhorn 43 Moos 53 Oberer Tiefbach 62 Furgg – Furi 71 Theodulgletscher 84 Ventina Glacier 4 Plan Torrette 22 Cieloalto 2 15a Sigari 5 Eisfluh 14 Kumme 26 Grünsee 35 Gifthittli 44 Hohtälli 54 Hörnli 63 Sandiger Boden 72 Furggsattel 85 Matterhorn glacier 5 Plan Maison-Cervinia 24 Pancheron VALTOURNENCHE -

Sir Walter Scott's Templar Construct

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. SIR WALTER SCOTT’S TEMPLAR CONSTRUCT – A STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY INFLUENCES ON HISTORICAL PERCEPTIONS. A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, EXTRAMURAL, NEW ZEALAND. JANE HELEN WOODGER 2017 1 ABSTRACT Sir Walter Scott was a writer of historical fiction, but how accurate are his portrayals? The novels Ivanhoe and Talisman both feature Templars as the antagonists. Scott’s works display he had a fundamental knowledge of the Order and their fall. However, the novels are fiction, and the accuracy of some of the author’s depictions are questionable. As a result, the novels are more representative of events and thinking of the early nineteenth century than any other period. The main theme in both novels is the importance of unity and illustrating the destructive nature of any division. The protagonists unify under the banner of King Richard and the Templars pursue a course of independence. Scott’s works also helped to formulate notions of Scottish identity, Freemasonry (and their alleged forbearers the Templars) and Victorian behaviours. However, Scott’s image is only one of a long history of Templars featuring in literature over the centuries. Like Scott, the previous renditions of the Templars are more illustrations of the contemporary than historical accounts. One matter for unease in the early 1800s was religion and Catholic Emancipation.