History and Politics in French Language Comics and Graphic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linguapax Review 2010 Linguapax Review 2010

LINGUAPAX REVIEW 2010 MATERIALS / 6 / MATERIALS Col·lecció Materials, 6 Linguapax Review 2010 Linguapax Review 2010 Col·lecció Materials, 6 Primera edició: febrer de 2011 Editat per: Amb el suport de : Coordinació editorial: Josep Cru i Lachman Khubchandani Traduccions a l’anglès: Kari Friedenson i Victoria Pounce Revisió dels textos originals en anglès: Kari Friedenson Revisió dels textos originals en francès: Alain Hidoine Disseny i maquetació: Monflorit Eddicions i Assessoraments, sl. ISBN: 978-84-15057-12-3 Els continguts d’aquesta publicació estan subjectes a una llicència de Reconeixe- ment-No comercial-Compartir 2.5 de Creative Commons. Se’n permet còpia, dis- tribució i comunicació pública sense ús comercial, sempre que se’n citi l’autoria i la distribució de les possibles obres derivades es faci amb una llicència igual a la que regula l’obra original. La llicència completa es pot consultar a: «http://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/es/deed.ca» LINGUAPAX REVIEW 2010 Centre UNESCO de Catalunya Barcelona, 2011 4 CONTENTS PRESENTATION Miquel Àngel Essomba 6 FOREWORD Josep Cru 8 1. THE HISTORY OF LINGUAPAX 1.1 Materials for a history of Linguapax 11 Fèlix Martí 1.2 The beginnings of Linguapax 14 Miquel Siguan 1.3 Les débuts du projet Linguapax et sa mise en place 17 au siège de l’UNESCO Joseph Poth 1.4 FIPLV and Linguapax: A Quasi-autobiographical 23 Account Denis Cunningham 1.5 Defending linguistic and cultural diversity 36 1.5 La defensa de la diversitat lingüística i cultural Fèlix Martí 2. GLIMPSES INTO THE WORLD’S LANGUAGES TODAY 2.1 Living together in a multilingual world. -

Plan Bruxellesbda4.Cdr

kaai ken A 42 es h c ni Pé es i d Qua YSER IJZER pl. de l’Yser pl. de l’Yser Ijzerpl. B Ijzerpl. D. BAUDOU B D. D IN ’ANV ERS i a a B ndelsk AU a DEW H ANTWER IJNLA AN erce PSE m LAA N u Com d i ROGIER Qua at tra s en 38 ak 5 L AN tr. pems p LF MAXLA O ADO ve m e Neu he u 6 p r ’O d . r e Porte de Flandre u ie r r ue de Flandre Vlaa 7 m ndere ordstr a Vlaamse Poort nstr. b 39 AX m u D Sleep Wel M a d D e u r rue OLPHE AD ru d e e ken D. A F B n ae toi lan tr. n e L e D dre s d a e euw ns V u i r ae la N r a t n pl. Centre Belge d er an De Brouckère de la a en str. STE-CATHERINE pl. Bande-Dessinée co l rue e ru tr. h e on s ST.-KATELIJNE d c du oubl Z es H and S ab Pa 8 st le raat s rd a v A e n ul to o in Muntcentrum B e St.-Kalelijne pl. D Centre 4 a pl.Ste.-Catherine nsa Monnaie . e DEBROUCKERE e r rt Muntpl. st ièr r. r enst ue pl. de la dr l o d ou t e Monnaie k AN l an itm r A ’Ecu a P a L l Porte et pl. -

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime

SAN DIEGO PUBLIC LIBRARY PATHFINDER Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime The Central Library has a large collection of comics, the Usual Extra Rarities, 1935–36 (2005) by George graphic novels, manga, anime, and related movies. The Herriman. 741.5973/HERRIMAN materials listed below are just a small selection of these items, many of which are also available at one or more Lions and Tigers and Crocs, Oh My!: A Pearls before of the 35 branch libraries. Swine Treasury (2006) by Stephan Pastis. GN 741.5973/PASTIS Catalog You can locate books and other items by searching the The War Within: One Step at a Time: A Doonesbury library catalog (www.sandiegolibrary.org) on your Book (2006) by G. B. Trudeau. 741.5973/TRUDEAU home computer or a library computer. Here are a few subject headings that you can search for to find Graphic Novels: additional relevant materials: Alan Moore: Wild Worlds (2007) by Alan Moore. cartoons and comics GN FIC/MOORE comic books, strips, etc. graphic novels Alice in Sunderland (2007) by Bryan Talbot. graphic novels—Japan GN FIC/TALBOT To locate materials by a specific author, use the last The Black Diamond Detective Agency: Containing name followed by the first name (for example, Eisner, Mayhem, Mystery, Romance, Mine Shafts, Bullets, Will) and select “author” from the drop-down list. To Framed as a Graphic Narrative (2007) by Eddie limit your search to a specific type of item, such as DVD, Campbell. GN FIC/CAMPBELL click on the Advanced Catalog Search link and then select from the Type drop-down list. -

Republique Democratique Du Congo

ETUDE DE L’IMPACT DES ARTS, DE LA CULTURE ET DES INDUSTRIES CREATIVES SUR L’ ECONOMIE EN AFRIQUE REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Projet développé et exécuté par Agoralumiere en collaboration avec CAJ(Afrique du Sud) commandé par ARTerial Network et financé par la Foundation DOEN , la Foundation Stomme et la République Fédérale du Nigeria Ministry of Commerce and Industry Federal Republic of Nigeria Democratic Republic of Congo Africa Union www.creative-africa.org Agoralumiere 2009 Remerciements Cette étude pilote a été commandée par ARTERIAL NETWORK et conjointement financée par STICHTING DOEN, la Fondation STROMME et le Gouvernement de la République Fédérale du Nigeria. Agoralumiere a été soutenue par l’Union Africaine pour la conduite de ce travail de recherche pilote dans le cadre de la mise en œuvre du Plan d’Action des Industries Culturelles et Créatives reformulé par Agoralumiere à la demande de la Commission et qui fut adopté en octobre 2008 par les Ministres de la Culture de l’Union Africaine. Agoralumiere a aussi été soutenue par le gouvernement de la République Démocratique du Congo, et particulièrement par le Cabinet du Premier Ministre qui entend utiliser ce travail de base pour élaborer une suite plus approfondie au niveau national, avec des chercheurs nationaux déjà formés dans le secteur. Agoralumiere a enfin été soutenue par le Dr Bamanga Tukur, Président du African Business Roundtable et du NEPAD Business Group. Agoralumiere tient à remercier tous ceux dont la participation directe et la contribution indirecte ont appuyé -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

Bruxelles, Capitale De La Bande Dessinée Dossier Thématique 1

bruxelles, capitale de la bande dessinée dossier thématique 1. BRUXELLES ET LA BANDE DESSINÉE a. Naissance de la BD à Bruxelles b. Du héros de BD à la vedette de cinéma 2. LA BANDE DESSINÉE, PATRIMOINE DE BRUXELLES a. Publications BD b. Les fresques BD c. Les bâtiments et statues incontournables d. Les musées, expositions et galeries 3. LES ACTIVITÉS ET ÉVÈNEMENTS BD RÉCURRENTS a. Fête de la BD b. Les différents rendez-vous BD à Bruxelles c. Visites guidées 4. SHOPPING BD a. Adresses b. Librairies 5. RESTAURANTS BD 6. HÔTELS BD 7. CONTACTS UTILES www.visitbrussels.be/comics BRUXELLES EST LA CAPITALE DE LA BANDE DESSINEE ! DANS CHAQUE QUARTIER, AU DÉTOUR DES RUES ET RUELLES BRUXELLOISES, LA BANDE DESSINÉE EST PAR- TOUT. ELLE EST UNE FIERTÉ NATIONALE ET CELA SE RES- SENT PARTICULIÈREMENT DANS NOTRE CAPITALE. EN EFFET, LES AUTEURS BRUXELLOIS AYANT CONTRIBUÉ À L’ESSOR DU 9ÈME ART SONT NOMBREUX. VOUS L’APPRENDREZ EN VISITANT UN CENTRE ENTIÈREMENT DÉDIÉ À LA BANDE DESSINÉE, EN VOUS BALADANT AU CŒUR D’UN « VILLAGE BD » OU ENCORE EN RENCON- TRANT DES FIGURINES MONUMENTALES ISSUES DE PLUSIEURS ALBUMS D’AUTEURS BELGES… LA BANDE DESSINÉE EST UN ART À PART ENTIÈRE DONT LES BRUX- ELLOIS SONT PARTICULIÈREMENT FRIANDS. www.visitbrussels.be/comics 1. BRUXELLES ET LA BANDE DESSINEE A. NAISSANCE DE LA BD À BRUXELLES Raconter des histoires à travers une succession d’images a toujours existé aux quatre coins du monde. Cependant, les spéciali- stes s’accordent à dire que la Belgique est incontournable dans le milieu de ce que l’on appelle aujourd’hui la bande dessinée. -

Hergé and Tintin

Hergé and Tintin PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 20 Jan 2012 15:32:26 UTC Contents Articles Hergé 1 Hergé 1 The Adventures of Tintin 11 The Adventures of Tintin 11 Tintin in the Land of the Soviets 30 Tintin in the Congo 37 Tintin in America 44 Cigars of the Pharaoh 47 The Blue Lotus 53 The Broken Ear 58 The Black Island 63 King Ottokar's Sceptre 68 The Crab with the Golden Claws 73 The Shooting Star 76 The Secret of the Unicorn 80 Red Rackham's Treasure 85 The Seven Crystal Balls 90 Prisoners of the Sun 94 Land of Black Gold 97 Destination Moon 102 Explorers on the Moon 105 The Calculus Affair 110 The Red Sea Sharks 114 Tintin in Tibet 118 The Castafiore Emerald 124 Flight 714 126 Tintin and the Picaros 129 Tintin and Alph-Art 132 Publications of Tintin 137 Le Petit Vingtième 137 Le Soir 140 Tintin magazine 141 Casterman 146 Methuen Publishing 147 Tintin characters 150 List of characters 150 Captain Haddock 170 Professor Calculus 173 Thomson and Thompson 177 Rastapopoulos 180 Bianca Castafiore 182 Chang Chong-Chen 184 Nestor 187 Locations in Tintin 188 Settings in The Adventures of Tintin 188 Borduria 192 Bordurian 194 Marlinspike Hall 196 San Theodoros 198 Syldavia 202 Syldavian 207 Tintin in other media 212 Tintin books, films, and media 212 Tintin on postage stamps 216 Tintin coins 217 Books featuring Tintin 218 Tintin's Travel Diaries 218 Tintin television series 219 Hergé's Adventures of Tintin 219 The Adventures of Tintin 222 Tintin films -

Jornal Do Próximo Futuro

SECÇÃOFICHA TÉCNICA FUNDAÇÃO CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN FUNDAÇÃO CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN PRÓXIMO FUTURO / NEXT FUTURE PRÓXIMO FUTURO / NEXT FUTURE PÁGINA: 2 PÁGINA: 3 Nuno Cera Futureland, Cidade do Mexico, 2009 Cortesia do artista e da Galeria Cortesía del artista y de la Galería Courtesy of the artist and of the Gallery Pedro Cera, Lisboa → Próximo Futuro é um Programa Gulbenkian de Cultura Contemporânea dedicado em particular, mas não exclusivamente, à investigação e criação na Europa, na América Latina e Caraíbas e em África. O seu calendário de realização é do Verão de 2009 ao fim de 2011. MARÇO NEXT FUTURE Próximo Futuro es un Programa Gulbenkian de Cultura Contemporánea dedicado, particular MARZO aunque no exclusivamente, a la investigación y la creación en Europa, África, América Latina y el Caribe. Su calendario de realización transcurrirá entre el verano de 2009 y 2011. MARCH PRÓXIMO FUTURO Next Future is a Gulbenkian Programme of Contemporary Culture dedicated in particular, but not exclusively, to research and creation in Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Baudouin Mouanda “Borders” is the theme of the exhibition of photography by Afri- Africa. It will be held from Summer 2009 to Cortesia do artista / Cortesía del artista / can and Afro-American artists, which will be opening on 13 May. FRONTERAS Isabel Mota the end of 2011. Courtesy of the artist It is not the first time that such a theme has been included in the programme of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, for several BORDERS seminars and workshops have already been held on this topic, together with the production of films and the organisation of “Fronteras” es el tema de la exposición de fotografía de artistas performances and shows. -

The Internment and Repatriation of the Japanese-French Nationals Resident in New Caledonia, 1941–1946

PORTAL Journal of RESEARCH ARTICLE Multidisciplinary The Internment and Repatriation of the International Studies Japanese-French Nationals Resident in Vol. 14, No. 2 September 2017 New Caledonia, 1941–1946 Rowena G. Ward Communities Acting for Sustainability in the Pacific University of Wollongong Special Issue, guest edited by Anu Bissoonauth and Rowena Corresponding author: Dr Rowena G. Ward, Senior Lecturer in Japanese, School of Humanities Ward. and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, Northfields Avenue, Wollongong NSW 2522, Australia. [email protected] DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/portal.v14i2.5478 © 2017 by the author(s). This Article History: Received 03/04/2017; Revised 16/07/2017; Accepted 18/06/2017; is an Open Access article Published 05/10/2017 distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Abstract Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ The pre-1941 Japanese population of New Caledonia was decimated by the French by/4.0/), allowing third parties administration’s decision to transfer most of the Japanese residents to Australia for internment to copy and redistribute the at the outbreak of the Asia-Pacific theatre of the Second World War. Among the men material in any medium transferred to Australia were ten men who had been formerly French nationals but had lost or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the their French nationality by decree. The French Administration’s ability to denationalise and material for any purpose, even intern, and then subsequently repatriate, the former-Japanese French-nationals was possible commercially, provided the due to changes to the French nationality laws and regulations introduced by the Vichy regime. -

EDITORIAL: SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL of COMIC ART VOL. 1: 2 (AUTUMN 2012) by the Editorial Team

EDITORIAL: SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF COMIC ART VOL. 1: 2 (AUTUMN 2012) by the Editorial Team SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF COMIC ART (SJOCA) VOL. 1: 2 (AUTUMN 2012) Everything starts with a First step – but to keep going with a sustained eFFort is what really makes for change. This is the second issue of the Scandinavian Journal of Comic Art and its release makes us just as proud – if not even more so – as we were when the very First issue was published last spring. We are also immensely proud to be part oF the recently awaKened and steadily growing movement oF academic research on comics in the Nordic countries. Since our First issue was published, another three Nordic comics scholars have had their PhDs accepted and several more PhD students researching comics have entered the academic system. Comics studies is noticeably growing in the Nordic countries at the moment and SJoCA is happy to be a part of this exciting development. SJoCA was initiated to ensure that there is a serious, peer reviewed and most importantly continuous publishing venue for scholars from the Scandinavian countries and beyond who want to research and write about all the diFFerent aspects oF comics. In order to Keep this idea alive, SJoCA is in constant need of interesting, groundbreaKing and thought-provoking texts. So, do send us everything from abstracts to full fledged manuscripts, and taKe part in maKing the field of Nordic comics research grow. – 2 – SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF COMIC ART (SJOCA) VOL. 1: 2 (AUTUMN 2012) “TO EMERGE FROM ITS TRANSITIONAL FUNK”: THE AMAZING ADVENTURES OF KAVALIER & CLAY’S INTERMEDIAL DIALOGUE WITH COMICS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS by Florian Groß ABSTRACT ThE artIclE tracEs thE currENt crItIcal dEbatE oN thE phENomENoN of thE graphIc Novel through an analysIs of MIchael ChaboN’s Novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000). -

Korean Webtoonist Yoon Tae Ho: History, Webtoon Industry, and Transmedia Storytelling

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), Feature 2216–2230 1932–8036/2019FEA0002 Korean Webtoonist Yoon Tae Ho: History, Webtoon Industry, and Transmedia Storytelling DAL YONG JIN1 Simon Fraser University, Canada At the Asian Transmedia Storytelling in the Age of Digital Media Conference held in Vancouver, Canada, June 8–9, 2018, webtoonist Yoon Tae Ho as a keynote speaker shared several interesting and important inside stories people would not otherwise hear easily. He also provided his experience with, ideas about, and vision for transmedia storytelling during in-depth interviews with me, the organizer of the conference. I divide this article into two major sections—Yoon’s keynote speech in the first part and the interview in the second part—to give readers engaging and interesting perspectives on webtoons and transmedia storytelling. I organized his talk into several major subcategories based on key dimensions. I expect that this kind of unusual documentation of this famous webtoonist will shed light on our discussions about Korean webtoons and their transmedia storytelling prospects. Keywords: webtoon, manhwa, Yoon Tae Ho, transmedia, history Introduction Korean webtoons have come to make up one of the most significant youth cultures as well as snack cultures: Audiences consume popular culture like webtoons and Web dramas within 10 minutes on their notebook computers or smartphones (Jin, 2019; Miller, 2007). The Korean webtoon industry has grown rapidly, and many talented webtoonists, including Ju Ho-min, Kang Full, and Yoon Tae Ho, are now among the most famous and successful webtoonists since the mid-2000s. Their webtoons—in particular, Yoon Tae Ho’s, including Moss (Ikki, 2008–2009), Misaeng (2012–2013), and Inside Men (2010–in progress)—have gained huge popularity, and all were successfully transformed into films, television dramas, and digital games. -

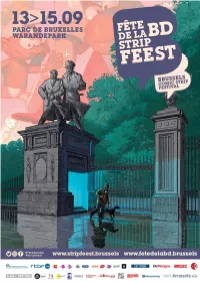

2019-09-12-Pk-Fbd-Final.Pdf

PRESS KIT Brussels, September 2019 The 2019 Brussels Comic Strip Festival Brussels is holding its 10th annual Comic Strip Festival from 13 to 15 September 2019 From their beginning at the turn of the previous century, Belgian comics have really become famous the world over. Many illustrators and writers from our country and its capital are well- known beyond our borders. That is reason enough to dedicate a weekend to this rich cultural heritage. Since its debut in 2010, the Brussels Comic Strip Festival has become the main event for comics fans. Young and old, novices and experts, all share a passion for the ninth art and come together each year to participate in the variety of activities on offer. More than 100,000 people and some 300 famous authors gather every year. For this 2019 edition, the essential events are definitely on the schedule: autograph sessions, the Balloon's Day Parade and many more. There's a whole range of activities to delight everyone. Besides the Parc de Bruxelles, le Brussels Comic Strip Festival takes over the prestigious setting of Brussels' Palais des Beaux-Arts, BOZAR. Two places that pair phenomenally well together for the Brussels Comic Strip Festival. Festival-goers will be able to stroll along as they please, enjoying countless activities and novelties on offer wherever they go. From hundreds of autograph signings to premiere cartoon screenings and multiple exhibitions and encounters with professionals, ninth art fans will have plenty to keep them entertained. Finally, the Brussels Comic Strip Festival will award comics prizes: The Atomium Prizes, during a gala evening when no less than €90,000 will be awarded for the best new works from the past year.