A Comparative Assessment of Deliberative Claims: the Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Method of Agile Pattern Creation for Campus Building: the Keio-SFC Experiment

The Method of Agile Pattern Creation for Campus Building: The Keio-SFC Experiment TAKASHI IBA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University NORIHIKO KIMURA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University TAKUYA HONDA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University SUMIRE NAKAMURA, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University SAKURAKO KOGURE, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University AYAKA YOSHIKAWA, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University In this paper, we address the method and practice of continuously creating pattern language in any phase of designing the campus, as an agile design method involving the campus users. The process of creating pattern language grasps and discloses discoveries and findings in campus planning, enabling all the users to pursue their ideal campus. The patterns that were shaped can be categorized into three domains; architecture and landscape, educational programs, and internal activities for campus planning. This paper also adopts the practical example of the campus planning process of a residential education and research facility, called Student Build Campus SBC), an initiative that allows people to create their own campus at Keio University, Shonan Fujisawa Campus (SFC) in Japan. Our research is based on architect Christopher Alexander’s studies on the Oregon Experiment and the construction of Eishin Campus School. We also present the point in which the process of creating pattern language follows the research studies from the agile design method -

Saying Bye to Blanchard

OREGON DAILY Emerald DAILYEMERALD . COM THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER AT THE UNIVERSITY OF OREGON SINCE 1900 VOL. 112, ISSUE 55 FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 2010 WHY STUDENT CONDUCT TOUGH TEST GLOBAL PRIVACY CODE MATTERS Volleyball prepares to face No. 10 UCLA Taken too far? Google Inc.’s NEWS | PAGE 3 and No. 6 USC, strives for NCAA berth investigation raises questions EXTREME ROOMMATES SPORTS | PAGE 5 NEWS | PAGE 3 OPINION | PAGE 2 STATE Understanding the ‘New Partnership’ President Lariviere believes an form, proposes a shift away from the “You can see that there is a individualized governing board centralized governance of the State Board tremendous and growing burden on mid- of Higher Education by creating a more dle-class families who send their students will keep tuition costs at bay localized governing board, as well as the to us for education,” Lariviere said in the STEFAN VERBANO creation of a new $1.6 billion endowment article. “It threatens to put higher educa- NEWS REPORTER composed of state and private funds. tion beyond the reach of an expanding In a fall 2010 Oregon Quarterly article, segment of worthy students, and that is a A culture of boom-and-bust funding University President Richard Lariviere frightening prospect for all of us.” for Oregon’s higher education system left said the new plan was catalyzed by past As a result, Lariviere’s argument the University considering drastic, untest- years of fiscal uncertainty, which often for the change in funding holds that ed changes to its systems of governance, left the school scrambling to manage its middle-class Oregonians are accountability and funding. -

Agile Design Process with Patterns for Campus Building

Agile Design Process with Patterns for Campus Building The Keio-SFC Experiment Takashi Iba *1 Norihiko Kimura *1 Takuya Honda *1 Sumire Nakamura *2 Sakurako Kogure *2 Ayaka Yoshikawa *2 *1 Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University *2 Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University In this paper, we address the method and practice of continuously creating pattern language before, dur- ing, and after the process of shaping the campus, as an agile design method involving the campus users. The process of creating pattern language that grasps discoveries and findings in campus planning is dis- closing and enables all the users to pursue their ideal campus. The patterns that were shaped can be cate- gorized in three domains; architecture and landscape, educational programs, and internal activities for campus planning. This paper also adopts the practical example of the campus planning process of a residential education and research facility, called Student Build Campus, an initiative that allows people to create their own campus at Keio University, Shonan Fujisawa Campus in Japan. Our research is based on architect Christopher Alexander’s studies on the Oregon Experiment and the construction of Eishin Gakuen Hi- gashino High School. We also present the point in which the process of creating pattern language follows the research studies from the agile design method developed in the field of software design. 1. INTRODUCTION Since its opening in 1990 as Keio University's "experimental campus," Shonan Fujisawa Cam- pus (SFC)1 has been the forefront of educational innovation in Japan. Launching practical re- search of project-based learning, online classes, multiple language classes, Self-Recommended Admissions (A.O. -

Christopher Alexander

Essay A Search for Beauty/A Struggle with Complexity: Christopher Alexander Richard P. Gabriel 1,∗,† and Jenny Quillien 2,∗,† 1 Hasso Plattner Institute, Redwood City, CA 94062, USA 2 Laboratory of Anthropology, Museum Hill, Santa Fe, NM 87505, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.P.G.); [email protected] (J.Q.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 28 May 2019; Accepted: 9 June 2019; Published: 16 June 2019 Abstract: Beauty. Christopher Alexander’s prolific journey in building, writing, and teaching was fueled by a relentless search for Beauty and its meaning. While all around him the world was intent on figuring out how to simplify, Alexander came to embrace complexity as the only path to his goal. The Beauty and life of that which he encountered and appreciated—an Indian village, a city, a subway network, an old Turkish carpet, or a campus—lay in its well-ordered complexity. As a designer and maker he found that simplicity came from choosing—at every step—the simplest way to add the necessary complexity. The failure of so much of our modern world, in Alexander’s eyes, was oversimplification, wantonly bulldozing context, misunderstanding the relationships of part and whole, ignoring the required role of time in the shaping of shapes, and ultimately dismissing, like Esau, our birthright of Value in favor of a lentil pottage of mere Fact. Ever elusive, Beauty demands of her suitors a constant return of attention to see what might be newly revealed, and Alexander duly returned again and again in pursuit of the mystery. In this essay—essentially biographical and descriptive of one man’s endeavors—we examine the full arc of his work from dissertation to most recent memoir. -

North Waterfront LRS.Indd

LANDSCAPE RESOURCE SURVEY University of Oregon Campus Heritage Landscape Plan Eugene, Lane County, Oregon • June 6, 2016 RESOURCE IDENTIFICATION & SUMMARY LANDSCAPE AREA NAME North Waterfront North Waterfront HISTORIC NAME(S) Unknown CAMPUS PLAN DESIGNATION Designated Open Space (DOS) CURRENT HISTORIC DESIGNATION N/A ERA(S) OF GREATEST SIGNIFICANCE Mid-Century (1947 - 1974) LEVEL OF SIGNIFICANCE Low LEVEL OF INTEGRITY Medium RANKING Ariel of North Waterfront Site Boundary with the main University of Oregon Tertiary Campus to the south Aeiral of North Waterfront Site Boundary University of Oregon North Waterfront 1 Landscape Resource Survey Landscape Resource Survey North Waterfront LANDSCAPE AREA CIRCULATION MAP — Highlighting existing elements from the period of significance and today. Autzen Foot Bridge Millrace Riverfront Field Circulation Loop Construction and Fill site Bike and Pedestrian Path Connection to Autzen Foot Bridge and circulation loop University of Oregon 2 North Waterfront Landscape Resource Survey Landscape Resource Survey North Waterfront SUMMARY OF EXISTING HISTORIC FEATURES Millrace, fill area, Autzen Foot Bridge and some open space. MIllrace connection to Willamette River Fenced off fill area Diagram of the Willamette River’s meandering nature University of Oregon North Waterfront 3 Landscape Resource Survey Landscape Resource Survey North Waterfront RESOURCE HISTORY ERA(S) OF GREATEST SIGNIFICANCE Designated Eras within the Period of Historic Significance Determined for this Survey are listed below. Check the era/eras determined to be of highest significance for this landscape area. Inception Era (1876 - 1913) Lawrence/ Cuthbert Era (1914 - 1946) X Mid-Century Era (1947 - 1974) The Oregon Experiment Era (1975 - present) DATE(S) OF CONSTRUCTION DURING ERA(S) 1925 Sanborn Map, close-up of gravel excavation area located at OF SIGNIFICANCE the western portion of the Waterfront site. -

Building on a Hill Buildings Around Quadrangles Buildings As Objects

1876 of Chapman Hall used to house the UO Bookstore and is now occupied by the Graduate School. It was Building On A Hill also Lawrence’s last work on the quadrangle, one of six (Condon Hall, Knight Library, Jordan Schnitzer UO Week of Welcome Museum of Art, Chapman Hall, Peterson Hall, and Gilbert Hall). FR AN KL IN B 1. The UO campus began on eighteen acres formerly known as Shaw Hill, a bluff near the Willamette E 11TH AVE OU LEV 4. The Library and Art Museum sat in a great open lawn that stretched all the way to Kincaid. The Art ARD River. Deady Hall was the frst building occupying the high point in a broad empty feld. The only trees Dads’ Gates Museum was built frst, in 1930, and is an outstanding example of the use of decorative brick. The on campus were three oaks to the north of Villard Hall; one still stands today. Instead of a carefully English Oaks that front the building were planted in 1940 and are a defning landscape feature for 2 kept lawn, the whole campus was native grasses where wild strawberries bloomed in season. During Northwest Robinson Theatre both the museum and the Memorial Quadrangle. The original portion of the Knight Library also was Christian McKenzie Villard the early years all travel to and from the university was up 12th Avenue and up the broad walk, the College Miller funded by the PWA and is representative of the last surge of building before WWII. The library has Theatre Lawrence frst formal entrance leading straight to the college steps. -

Summer Issue a Tale of Two Lincolns

OREGON SEPTEMBER, 2004 VOLUME XXI ISSUE XIV & XV A JOURNAL OF OPINION Summer Issue A Tale of Two Lincolns Plus: Tater Awards Staff Farewells and Year in Review MISSION STATEMENT The OREGON COMMENTATOR is an independent journal of opinion published at the University of Oregon for the campus community. FOUNDED SEPT. 27, 1983 • MEMBER COLLEGIATE NETWORK Founded by a group of concerned student journalists Sept. 27 1983, the COMMENTATOR has had a major impact in the “war of ideas” on campus, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PUBLISHER Tyler Graf Erin Flood providing students with an alternative to the left-wing orthodoxy promoted by other student publications, professors and student groups. During its nineteen-year existence, it has enabled University students to hear both sides of issues. Our paper combines reporting with opinion, PRODUCTION MANAGER Jeremy Jones humor and feature articles. We have won national recognition for our commitment to journalistic excellence. The OREGON COMMENTATOR is operated as a program of the Associated Students of the University of Oregon (ASUO) and is staffed CONTRIBUTING EDITOR solely by volunteer editors and writers. The paper is funded through Dan Atkinson student incidental fees, advertising revenue and private donations. We print a wide variety of material, but our main purpose is to show students that a political philosophy of conservatism, free thought and individual liberty is an intelligent way of looking at the world — contrary to what they might hear in classrooms and on campus. In general, editors of the CONTRIBUTORS COMMENTATOR share beliefs in the following: Jeremy Berrington, Ben Brown, Matt Haulk, Dave Kirk , Matt Misley, Olly Ruff • We believe that the University should be a forum for rational and BOARD OF DIRECTORS informed debate — instead of the current climate in which ideological Tyler Graf, Chairman dogma, political correctness, fashion and mob mentality interfere with Dan Atkinson, Director, Olly Ruff, Director academic pursuit. -

The Library of Professor Julian Beinart

Urbanism The Library of Professor Julian Beinart Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Department of Architecture. 1458 titles in circa 1570 physical volumes ARS LIBRI QUOTATION 1 ABERCROMBIE, PATRICK. Greater London Plan 1944. A report prepared on behalf of the Standing Conference on London Regional Planning...at the request of the Minister of Town and Country Planning. x, 220, (2)pp. 2 lrg. folding plans, loose in rear pocket, as issued. Prof. illus. Sm. folio. Cloth. London (HMSO), 1945. 2 ABRAMS, CHARLES. Housing in the Modern World. Man’s struggle for shelter in an urbanizing world. With an introduction by Peter Self. xv, (1), 307pp. 46 illus. hors texte. Wraps. London (Faber and Faber), 1969. 3 ABRAMS, CHARLES. Man’s Struggle for Shelter in an Urbanizing World. (The Joint Center for Urban Studies of The Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University.) xi, (1), 307pp. 46 illus. hors texte. Sm. 4to. Cloth. Cambridge (The M.I.T. Press), 1964. 4 ABRAMSON, PAUL. Schools for Early Childhood. A report from Educational Facilities Laboratories. Profiles of Significant Schools. 55pp. Prof. illus. 4to. Wraps. New York (Educational Facilities Laboratories), 1970. 5 ABU DHABI. MUBADALA DEVELOPMENT. Al Hikma. [Prospectus to design, build, own and operate the new campus for the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU) in Al Ain.] 17, 17, (2)pp. Illus. Lrg. sq. 8vo. Wraps. Parallel texts in English and Arabic. [Abu Dhabi, 2008?]. 6 ABU DHABI. MUBADALA DEVELOPMENT COMPANY. Inspired Investing. 34pp. Illus. 4to. Wraps. Abu Dhabi, [2005]. 7 ABU-LUGHOD, JANET L. Changing Cities: Urban Sociology. xi, (3), 430pp. Figs. 4to. Boards. -

To View As A

Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations A publication of the Willamette Heritage Center Editor and Curator: Keni Sturgeon, Willamette Heritage Center Kylie Pine, Willamette Heritage Center Editorial board: Gabriel Bennett, Oregon State University Dianne Huddleston, Independent Historian Chad Iwertz, Oregon State University Samantha Reining, Independent Historian Jennifer Ross, Western Oregon University Ross Sutherland, Bush House Museum © 2014 Willamette Heritage Center www.willametteheritage.org Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations is published by the Willamette Heritage Center at The Mill, 1313 Mill Street SE, Salem, OR 97301. Nothing in the journal may be reprinted in whole or part without written permission from the publisher. Direct inquiries to Kylie Pine, Curator, Willamette Heritage Center, 1313 Mill Street SE, Salem, OR 97301 or email [email protected]. 1 In This Issue Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations is the Willamette Heritage Center’s biannual publication. Its goal is to provide a showcase for scholarly writing pertaining to history and heritage in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, south of Portland. Articles are written by scholars, students, heritage professionals and historians - professional and amateur. Editions are themed to orient authors and readers to varied and important topics in Valley history. This issue looks into the topic of work in the Valley—a topic with many different facets despite its apparent universality. Articles in this edition focus on everything from the types work occupying valley residents to the way that work has shaped our communities. In addition to the articles, the edition includes a section called: “In Their Own Words,” our regular feature which provides access to primary sources found in the Willamette Heritage Center’s collections. -

Christopher Alexander - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 頁 1 / 9

Christopher Alexander - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 頁 1 / 9 Christopher Alexander From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Christopher Wolfgang Alexander (born 4 October 1936 in Vienna, Austria)[1][2] is a widely influential architect and design theorist, and currently emeritus professor at the University of California, Berkeley. His theories about the nature of human-centered design have had notable impacts across many fields beyond architecture, including urban design, software, sociology and other fields.[3] Alexander has also designed and personally built over 100 buildings, both as an architect and a general contractor.[4][5] In the field of software, Alexander is regarded as the father of Christopher Alexander in 2012. the Pattern Language movement. The first wiki - the technology behind Wikipedia - led directly from Alexander's work, according to its creator, Ward Cunningham.[6][7] Alexander's work has also influenced the development of Agile software development and Scrum (software development)[8] In architecture, Alexander's work is used by a number of different contemporary architectural communities of practice, including the New Urbanist movement, to help people to reclaim control over their own built environment.[9] However, Alexander is controversial among some mainstream architects and critics, in part because his work is often harshly critical of much of contemporary architectural theory and practice.[10] Alexander is known for his many books on the design and building process, including Notes on the Synthesis of Form, A City is Not a Tree (first published as a paper and recently re-published in book form), The Timeless Way of Building, A New Theory of Urban Design, and The Oregon Experiment. -

Foreword to the Third + Edition

NIVERSITY OF REGON AMPUS LAN + i U O C P - Third Edition, 2017 INTRO FOREWORD TO THE THIRD+ EDITION Third+ Edition (November 2017) Second Edition (2011, reprinted 2012) This third+ edition of the 2005 Campus Plan integrates amendments approved since 2005. The following changes were previously It also includes editorial and typographical incorporated into the second edition: corrections intended to clarify the original intent of the document as well as updated facts and Diversity figures. The approved plan amendments address A new diversity pattern and a revised the following areas: definition of the project user group ensures that the issue of diversity is considered Southeast Campus - Maximum Allowed during the project design to help create a Density campus that is welcoming to all. This amendment changes the maximum allowed density to accommodate the Jane East Campus Open-space Framework Sanders Softball Stadium Project. The Global Scholars Hall project triggered the requirement to prepare and adopt an East Campus - Maximum Allowed Density open-space framework plan for the affected This amendment changes the maximum area. allowed density to accommodate the New Residence Hall Project south of Global Historic Landscapes Scholar’s Hall. A new Historic Landscapes pattern and principle refinements address processes Third Edition (August 2014) for identifying and documenting historic landscapes. They provide a The following changes were previously framework for making decisions about incorporated into the third edition: preferred preservation actions and future development. East Campus Open-space Framework The Central Kitchen and Woodshop Project, Lewis Integrative Science Building (LISB) which is located in the East Campus Area, Open-space Amendments triggered the requirement to prepare and The LISB project triggered the need adopt an open-space framework plan for the to amend the campus’s open-space affected area (the block bounded by 17th framework. -

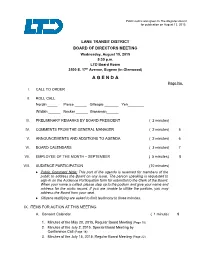

A G E N D a Page No

Public notice was given to The Register-Guard for publication on August 13, 2015. LANE TRANSIT DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING Wednesday, August 19, 2015 5:30 p.m. LTD Board Room 3500 E. 17th Avenue, Eugene (in Glenwood) A G E N D A Page No. I. CALL TO ORDER II. ROLL CALL Nordin _____ Pierce ______ Gillespie _______ Yeh________ Wildish ______ Necker ______ Grossman______ III. PRELIMINARY REMARKS BY BOARD PRESIDENT ( 2 minutes) IV. COMMENTS FROM THE GENERAL MANAGER ( 2 minutes) 5 V. ANNOUNCEMENTS AND ADDITIONS TO AGENDA ( 2 minutes) 6 VI. BOARD CALENDARS ( 3 minutes) 7 VII. EMPLOYEE OF THE MONTH – SEPTEMBER ( 5 minutes) 8 VIII. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION (10 minutes) Public Comment Note: This part of the agenda is reserved for members of the public to address the Board on any issue. The person speaking is requested to sign-in on the Audience Participation form for submittal to the Clerk of the Board. When your name is called, please step up to the podium and give your name and address for the audio record. If you are unable to utilize the podium, you may address the Board from your seat. Citizens testifying are asked to limit testimony to three minutes. IX. ITEMS FOR ACTION AT THIS MEETING A. Consent Calendar ( 1 minute) 9 1. Minutes of the May 20, 2015, Regular Board Meeting (Page 10) 2. Minutes of the July 2, 2015, Special Board Meeting by Conference Call (Page 18) 3. Minutes of the July 15, 2015, Regular Board Meeting (Page 22) Agenda – August 19, 2015 Page No.