To View As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: a Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: A Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A. Johnson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC LOGGING SONGS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST: A STUDY OF THREE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS By LESLIE A. JOHNSON A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Leslie A. Johnson defended on March 28, 2007. _____________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ` _____________________________ Karyl Louwenaar-Lueck Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have helped me with this manuscript and my academic career: my parents, grandparents, other family members and friends for their support; a handful of really good teachers from every educational and professional venture thus far, including my committee members at The Florida State University; a variety of resources for the project, including Dr. Jens Lund from Olympia, Washington; and the subjects themselves and their associates. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

SCPL Book Discussion Kits

Santa Cruz Public Libraries - Readers' Advisory Book Discussion Kits (All) Above All Things by Tanis Rideout A tale inspired by the life and mysterious fate of George Mallory traces the experiences of his wife, Ruth, who in 1924 maintains a hopeful vigil in war-ravaged England during Mallory's fateful third expedition to reach the summit of Mount Everest. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian by Sherman Alexie Budding cartoonist Junior leaves his troubled school on the Spokane Indian Reservation to attend an all-white farm town school where the only other Indian is the school mascot. The Adventures of the Blue Avenger by Norma Howe On his sixteenth birthday, still trying to cope with the unexpected death of his father, David Schumacher decides--or does he--to change his name to Blue Avenger, hoping to find a way to make a difference in his Oakland neighborhood and in the world. Al Capone Does My Shirts by Gennifer Choldenko A twelve-year-old boy named Moose moves to Alcatraz Island in 1935 when guards' families were housed there, and has to contend with his extraordinary new environment in addition to life with his autistic sister. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho An Andalusian shepherd boy named Santiago travels from his homeland in Spain to the Egyptian desert in search of treasure buried in the pyramids. Along the way he meets a Gypsy woman, a man who calls himself king, and an alchemist, all of whom point Santiago in the direction of his quest. What starts out as a journey to find worldly goods turns into a meditation on the treasures found within. -

2020 Oregon State Baseball Oregon State Yearly

Twitter.com/BeaverBaseball 2020 OREGON STATE BASEBALL Instagram.com/BeaverBaseball Facebook.com/OregonStateBaseball OREGON STATE YEARLY RECORDS Year-By-Year Records Year Coach Overall League Place Year Coach Overall League Place 1989 Jack Riley 27-23 15-9 2nd tie, Northern Division 1907 F.C. McReynolds 5-2 - - 1990 Jack Riley 30-22 15-9 2nd, Northern Division 1908 Joe Fay 11-4 - Oregon Collegiate Champs 1991 Jack Riley 28-20 12-8 2nd, Northern Division 1909 Otto Moore 5-4 - - 1992 Jack Riley 23-30 10-20 6th, Northern Division 1910 Fielder Jones 13-4-1 - Northwest Collegiate Champs 1993 Jack Riley 31-18 20-10 2nd, Northern Division 1911 Frederick Walker 8-7 - - 1994 Jack Riley 36-15 22-8 1st, Northern Division 1912 E.J. Stewart 5-9 - - 1995 Pat Casey 25-24-1 14-16 4th tie, Northern Division 1913 Jesse Garrett 7-10 4-4 1st tie, Northern Division West 1996 Pat Casey 32-16-1 14-10 2nd, Northern Division 1914 Wilkie Clark 7-9 1-7 3rd, Northern Division West 1997 Pat Casey 38-12-1 18-6 2nd, Northern Division 1915 Roy Goble 13-8 5-1 1st, Northern Division West 1998 Pat Casey 35-14-1 15-9 2nd, Northern Division 1916 Hans Loof 10-9-1 5-3 1st, Northern Division West 1999 Pat Casey 19-35 7-17 8th, Pacific-10 1917 No team - World War I 2000 Pat Casey 28-27 9-15 6th, Pacific-10 1918 J.D. Baldwin 4-6 - - 2001 Pat Casey 31-24 11-13 6th, Pacific-10 1919 Jimmie Richardson 7-7 2-5 2nd, Northern Division West 2002 Pat Casey 31-23 10-14 6th, Pacific-10 1920 Jimmie Richardson 12-11 11-8 -, Northern Division 2003 Pat Casey 25-28 7-17 8th tie, Pacific-10 1921 -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will fin d a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 12-1-2019 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century Beverley Rilett University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Rilett, Beverley, "British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century" (2019). Zea E-Books. 81. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. CHARLOTTE SMITH WILLIAM BLAKE WILLIAM WORDSWORTH SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE GEORGE GORDON BYRON PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY JOHN KEATS ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING ALFRED TENNYSON ROBERT BROWNING EMILY BRONTË GEORGE ELIOT MATTHEW ARNOLD GEORGE MEREDITH DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI CHRISTINA ROSSETTI OSCAR WILDE MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE ZEA BOOKS LINCOLN, NEBRASKA ISBN 978-1-60962-163-6 DOI 10.32873/UNL.DC.ZEA.1096 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. University of Nebraska —Lincoln Zea Books Lincoln, Nebraska Collection, notes, preface, and biographical sketches copyright © 2017 by Beverly Park Rilett. All poetry and images reproduced in this volume are in the public domain. ISBN: 978-1-60962-163-6 doi 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1096 Cover image: The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse, 1888 Zea Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries. -

Senators-Team-Stats-06282021.Pdf

Season Report Salem Senators Team Stats GAMES RUNS BATTING AVERAGE ON BASE PERCENTAGE SLUGGING PERCENTAGE HOME RUNS 21 84 .237 .312 .326 5 SCHEDULE SUMMARY STATISTICS CATEGORY OVERALL CONF Overall (Pct.) 3-18 (.143) Games 21 - Conference (Pct.) 0-0 (.000) At Bats 696 - Streak Lost 5 Runs 84 - Home 1-9 Hits 165 - Away 2-9 Doubles 39 - Neutral 0-0 Triples 4 - RECENT GAMES Home Runs 5 - Jun 18 at Salem-Keizer Volcanoes W, 6-4 Runs Batted In 77 - Jun 19 Campesinos de Salem Keizer L, 17-8 Extra Base Hits 48 0 Jun 20 at Portland Mavericks L, 2-0 Total Bases 227 0 Jun 24 Portland Mavericks L, 5-3 Walks 62 - Jun 26 Campesinos de Salem Keizer L, 10-5 Hit by pitch 16 - Jun 27 Salem-Keizer Volcanoes L, 4-1 Strikeouts 203 - Sacrifice Flies 6 - Sacrifice Hits 6 - Hit into double play 16 - Stolen Bases 15 - Caught Stealing 8 - Batting Average .237 - On Base Percentage .312 - Slugging Percentage .326 - Earned Run Average 7.76 0.00 Shutouts 0 - At Bats Against 715 - Batting Average Against .281 - Home Attendance 0 - Home Attendance average 0 - Player Stats HITTING NO. NAME YR POS G AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB K SB CS AVG OBP SLG 21 Angeddy Almanzar INF 21 70 10 13 2 1 1 6 11 20 1 0 .186 .293 .286 65 Blayze Arcano-Liacuna OF 3 9 1 4 1 0 0 1 0 4 0 0 .444 .545 .556 10 Rob Brown INF 20 72 9 20 5 0 0 6 2 19 3 2 .278 .299 .347 49 Tanner Cantwell 2 6 2 3 2 0 0 2 3 0 1 0 .500 .667 .833 22 Israel Cruz Pitcher 4 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 .000 .000 .000 12 John Dodson inf 3 10 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 .000 .000 .000 30 John Dodson 1 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 .000 .000 .000 5 Malcolm -

Nats Win at Last, Backing Good Pitching with Power to Trample

Farm,and Garden ■*•«**,Financial News __Junior Star_ 101(1^ Jgtflf jgptiTlg_Stomps _ WASHINGTON, I). C., APIIIL 21, 1946. :_■__ ___ Nats Win at Last, Backing Good Pitching With Power to Trample Yankees, 7-3 ★ ★ _____# ★ ★ ★ ★ ose or Assault Shines in Wood, Armed Lands Philadelphia at 'Graw By FRANCIS E. STANN --- 4 Heath's Benching Follows Simmons-Bonura Pattern AT LEAST ONE GOT BY —By Gib Crockett Test The benching of Outfielder Jeff Heath by the Nationals after Texas Ace Passes Derby less than a week of play is not without precedent. Heath, you re- Spence's Homer member, was acquired for one purpose—to hit that long, extra-base In Finish at Jamaica wallop for Washington. But so were A1 Simmons and Zeke Bonura Sizzling some years ago. Marine Simmons had been one of the greatest right- Heads Rips by Favored Hampden, Victory hand sluggers m the history of the American Slashing On to Win League. For that matter, iie may have been In Stretch, Goes 2-Length the absolute greatest. Critics generally rated By the Associated Press licked a $22,600 pay check for Simmons and Rogers Hornsby of the National f up 1 lis him a bank as 14-Hit NEW YORK, 20.—The Texas day's work, giving the two modern Attack League best of times. April ■oil of $30,100 for the year and The Milwaukee Pole was over the hill when terror from the wide open spaces,,’ 47,350 for his two seasons. Clark Griffith got him, but he still was a home Leonard, stretch-burning Assault, sizzled to a He’ll take the train ride to the run threat. -

Bush House Today Lies Chiefly in Its Rich, Unaltered Interior,Rn Which Includes Original Embossed French Wall Papers, Brass Fittings, and Elaborate Woodwork

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Oregon COUNTTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Mari on INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applica#ie\s&ctipns) / \ ' •• &•••» JAN 211974 COMMON: /W/' .- ' L7 w G I 17 i97«.i< ——————— Bush (Asahel) House —— U^ ——————————— AND/OR HISTORIC: \r«----. ^ „. I.... ; „,. .....,.„„.....,.,.„„,„,..,.,..,..,.,, , ,, . .....,,,.,,,M,^,,,,,,,,M,MM^;Mi,,,,^,,p'K.Qic:r,£: 'i-; |::::V^^:iX.::^:i:rtW^:^ :^^ Sii U:ljif&:ii!\::T;:*:WW:;::^^ STREET AND NUMBER: "^s / .•.-'.••-' ' '* ; , X •' V- ; '"."...,, - > 600 Mission Street s. F. W J , CITY OR TOWN: Oregon Second Congressional Dist. Salem Representative Al TJllman STATE CODE COUNT ^ : CO D E Oreeon 97301 41 Marien Q47 STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC r] District |t] Building SO Public Public Acquisit on: E Occupied Yes: r-, n . , D Restricted G Site Q Structure D Private Q ' n Process ( _| Unoccupied -j . —. _ X~l Unrestricted [ —[ Object | | Both [ | Being Consider ea Q Preservation work ^~ ' in progress ' — I PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government | | Park [~] Transportation l~l Comments | | Commercial CD Industrial | | Private Residence G Other (Specify) Q Educational d] Military Q Religious [ | Entertainment GsV Museum QJ] Scientific ...................... OWNER'S NAME: Ul (owner proponent of nomination) P ) ———————City of Salem————————————————————————————————————————— - ) -

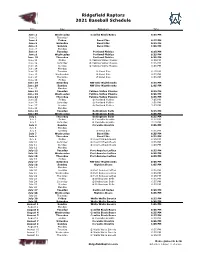

Ridgefield Raptors Game Schedule

Ridgefield Raptors 2021 Baseball Schedule Date Day Opponent Time June 2 Wednesday Cowlitz Black Bears 6:35 PM June 3 Thursday June 4 Friday Bend Elks 6:35 PM June 5 Saturday Bend Elks 6:35 PM June 6 Sunday Bend Elks 1:05 PM June 7 Monday June 8 Tuesday Portland Pickles 6:35 PM June 9 Wednesday Portland Pickles 6:35 PM June 10 Thursday Portland Pickles 6:35 PM June 11 Friday @ Yakima Valley Pippins 6:35 PM June 12 Saturday @ Yakima Valley Pippins 6:35 PM June 13 Sunday @ Yakima Valley Pippins 6:05 PM June 14 Monday June 15 Tuesday @ Bend Elks 6:35 PM June 16 Wednesday @ Bend Elks 6:35 PM June 17 Thursday @ Bend Elks 6:35 PM June 18 Friday June 19 Saturday NW Star Nighthawks 6:35 PM June 20 Sunday NW Star Nighthawks 1:05 PM June 21 Monday June 22 Tuesday Yakima Valley Pippins 6:35 PM June 23 Wednesday Yakima Valley Pippins 6:35 PM June 24 Thursday Yakima Valley Pippins 6:35 PM June 25 Friday @ Portland Pickles 7:05 PM June 26 Saturday @ Portland Pickles 7:05 PM June 27 Sunday @ Portland Pickles 5:05 PM June 28 Monday June 29 Tuesday Bellingham Bells 6:35 PM June 30 Wednesday Bellingham Bells 6:35 PM July 1 Thursday Bellingham Bells 6:35 PM July 2 Friday @ Corvallis Knights 6:30 PM July 3 Saturday @ Corvallis Knights 7:15 PM July 4 Sunday Corvallis Knights 3:05 PM July 5 Monday July 6 Tuesday @ Bend Elks 6:35 PM July 7 Wednesday Bend Elks 6:35 PM July 8 Thursday Bend Elks 6:35 PM July 9 Friday @ Cowlitz Black Bears 6:35 PM July 10 Saturday @ Cowlitz Black Bears 6:35 PM July 11 Sunday @ Cowlitz Black Bears 1:05 PM July 12 Monday July 13 Tuesday -

Hitchcock/ Truffaut

January / February 2016 Canadian & International Features The Heart of Madame Sabali NEW WORLD DOCUMENTARIES special events SHORTS & ARTIST TALKS Hitchcock/ Cabin Fever: Vinylside Chat Truffaut Free Films for Kids! with Alan Zweig www.winnipegcinematheque.com January/February Staff Picks the art direction and costumes in the film, which are both colourful and creative. The most refreshing element of McKenna’s film is the complexity of his characters, more specifically Marie Brassard who was amazing as Jeannette. This middle-aged woman was given more power and freedom to explore all types of relationships within the film, unlike films where we would normally see a woman of this age for a blink of a second. McKenna’s choice of casting such a strong lead pays off with depth to the plot and this film will not disappoint. Another screening that is not to be missed is Moving Perspectives (Feb 13) ↑ Left to right: A customer (Kristy Muckosky), Dave Barber, Eric Peterson, Cecilia Araneda, Heidi curated by Leslie Supnet. I feel like this is a Phillips, Kaitlyn McBurney, Jaimz Asmundson. Photo by Leif Norman. program that, while promising to put form over content, will not fail to entertain. I asked For 12 years now, January and February luck to you in your future endeavours! I’ll Supnet for a sneak peak and I can promise at Cinematheque have meant one very miss your goofy laugh. — Jaimz Asmundson, dancing, which is rare for program that special event: Cabin Fever! Every Sunday Cinematheque Programming Director focuses on personal cinema.— Heidi Phillips, at 2 pm, this free admission series offers Cinematheque Head Projectionist a variety of family friendly classics with The touring Canada’s Top Ten Film Festival made-in-Manitoba shorts. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

The Method of Agile Pattern Creation for Campus Building: the Keio-SFC Experiment

The Method of Agile Pattern Creation for Campus Building: The Keio-SFC Experiment TAKASHI IBA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University NORIHIKO KIMURA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University TAKUYA HONDA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University SUMIRE NAKAMURA, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University SAKURAKO KOGURE, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University AYAKA YOSHIKAWA, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University In this paper, we address the method and practice of continuously creating pattern language in any phase of designing the campus, as an agile design method involving the campus users. The process of creating pattern language grasps and discloses discoveries and findings in campus planning, enabling all the users to pursue their ideal campus. The patterns that were shaped can be categorized into three domains; architecture and landscape, educational programs, and internal activities for campus planning. This paper also adopts the practical example of the campus planning process of a residential education and research facility, called Student Build Campus SBC), an initiative that allows people to create their own campus at Keio University, Shonan Fujisawa Campus (SFC) in Japan. Our research is based on architect Christopher Alexander’s studies on the Oregon Experiment and the construction of Eishin Campus School. We also present the point in which the process of creating pattern language follows the research studies from the agile design method