Christopher Alexander's a Pattern Language: Analysing, Mapping And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patterns Senior Member of Technical Staff and Pattern Languages Knowledge Systems Corp

Kyle Brown An Introduction to Patterns Senior Member of Technical Staff and Pattern Languages Knowledge Systems Corp. 4001 Weston Parkway CSC591O Cary, North Carolina 27513-2303 April 7-9, 1997 919-481-4000 Raleigh, NC [email protected] http://www.ksccary.com Copyright (C) 1996, Kyle Brown, Bobby Woolf, and 1 2 Knowledge Systems Corp. All rights reserved. Overview Bobby Woolf Senior Member of Technical Staff O Patterns Knowledge Systems Corp. O Software Patterns 4001 Weston Parkway O Design Patterns Cary, North Carolina 27513-2303 O Architectural Patterns 919-481-4000 O Pattern Catalogs [email protected] O Pattern Languages http://www.ksccary.com 3 4 Patterns -- Why? Patterns -- Why? !@#$ O Learning software development is hard » Lots of new concepts O Must be some way to » Hard to distinguish good communicate better ideas from bad ones » Allow us to concentrate O Languages and on the problem frameworks are very O Patterns can provide the complex answer » Too much to explain » Much of their structure is incidental to our problem 5 6 Patterns -- What? Patterns -- Parts O Patterns are made up of four main parts O What is a pattern? » Title -- the name of the pattern » A solution to a problem in a context » Problem -- a statement of what the pattern solves » A structured way of representing design » Context -- a discussion of the constraints and information in prose and diagrams forces on the problem »A way of communicating design information from an expert to a novice » Solution -- a description of how to solve the problem » Generative: -

Neuroscience, the Natural Environment, and Building Design

Neuroscience, the Natural Environment, and Building Design. Nikos A. Salingaros, Professor of Mathematics, University of Texas at San Antonio. Kenneth G. Masden II, Associate Professor of Architecture, University of Texas at San Antonio. Presented at the Bringing Buildings to Life Conference, Yale University, 10-12 May 2006. Chapter 5 of: Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life, edited by Stephen R. Kellert, Judith Heerwagen, and Martin Mador (John Wiley, New York, 2008), pages 59-83. Abstract: The human mind is split between genetically-structured neural systems, and an internally-generated worldview. This split occurs in a way that can elicit contradictory mental processes for our actions, and the interpretation of our environment. Part of our perceptive system looks for information, whereas another part looks for meaning, and in so doing gives rise to cultural, philosophical, and ideological constructs. Architects have come to operate in this second domain almost exclusively, effectively neglecting the first domain. By imposing an artificial meaning on the built environment, contemporary architects contradict physical and natural processes, and thus create buildings and cities that are inhuman in their form, scale, and construction. A new effort has to be made to reconnect human beings to the buildings and places they inhabit. Biophilic design, as one of the most recent and viable reconnection theories, incorporates organic life into the built environment in an essential manner. Extending this logic, the building forms, articulations, and textures could themselves follow the same geometry found in all living forms. Empirical evidence confirms that designs which connect humans to the lived experience enhance our overall sense of wellbeing, with positive and therapeutic consequences on physiology. -

Open Source Architecture, Began in Much the Same Way As the Domus Article

About the Authors Carlo Ratti is an architect and engineer by training. He practices in Italy and teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he directs the Senseable City Lab. His work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale and MoMA in New York. Two of his projects were hailed by Time Magazine as ‘Best Invention of the Year’. He has been included in Blueprint Magazine’s ‘25 People who will Change the World of Design’ and Wired’s ‘Smart List 2012: 50 people who will change the world’. Matthew Claudel is a researcher at MIT’s Senseable City Lab. He studied architecture at Yale University, where he was awarded the 2013 Sudler Prize, Yale’s highest award for the arts. He has taught at MIT, is on the curatorial board of the Media Architecture Biennale, is an active protagonist of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s 89plus, and has presented widely as a critic, speaker, and artist in-residence. Adjunct Editors The authorship of this book was a collective endeavor. The text was developed by a team of contributing editors from the worlds of art, architecture, literature, and theory. Assaf Biderman Michele Bonino Ricky Burdett Pierre-Alain Croset Keller Easterling Giuliano da Empoli Joseph Grima N. John Habraken Alex Haw Hans Ulrich Obrist Alastair Parvin Ethel Baraona Pohl Tamar Shafrir Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: The Elements of Modern Architecture The New Autonomous House World Architecture: The Masterworks Mediterranean Modern See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com Contents -

Wiki As Pattern Language

Wiki as Pattern Language Ward Cunningham Cunningham and Cunningham, Inc.1 Sustasis Foundation Portland, Oregon Michael W. Mehaffy Faculty of Architecture Delft University of Technology2 Sustasis Foundation Portland, Oregon Abstract We describe the origin of wiki technology, which has become widely influential, and its relationship to the development of pattern languages in software. We show here how the relationship is deeper than previously understood, opening up the possibility of expanded capability for wikis, including a new generation of “federated” wiki. [NOTE TO REVIEWERS: This paper is part first-person history and part theory. The history is given by one of the participants, an original developer of wiki and co-developer of pattern language. The theory points toward future potential of pattern language within a federated, peer-to-peer framework.] 1. Introduction Wiki is today widely established as a kind of website that allows users to quickly and easily share, modify and improve information collaboratively (Leuf and Cunningham, 2001). It is described on Wikipedia – perhaps its best known example – as “a website which allows its users to add, modify, or delete its content via a web browser usually using a simplified markup language or a rich-text editor” (Wikipedia, 2013). Wiki is so well established, in fact, that a Google search engine result for the term displays approximately 1.25 billion page “hits”, or pages on the World Wide Web that include this term somewhere within their text (Google, 2013a). Along with this growth, the definition of what constitutes a “wiki” has broadened since its introduction in 1995. Consider the example of WikiLeaks, where editable content would defeat the purpose of the site. -

Enterprise Integration Patterns Introduction

Enterprise Integration Patterns Gregor Hohpe Sr. Architect, ThoughtWorks [email protected] July 23, 2002 Introduction Integration of applications and business processes is a top priority for many enterprises today. Requirements for improved customer service or self-service, rapidly changing business environments and support for mergers and acquisitions are major drivers for increased integration between existing “stovepipe” systems. Very few new business applications are being developed or deployed without a major focus on integration, essentially making integratability a defining quality of enterprise applications. Many different tools and technologies are available in the marketplace to address the inevitable complexities of integrating disparate systems. Enterprise Application Integration (EAI) tool suites offer proprietary messaging mechanisms, enriched with powerful tools for metadata management, visual editing of data transformations and a series of adapters for various popular business applications. Newer technologies such as the JMS specification and Web Services standards have intensified the focus on integration technologies and best practices. Architecting an integration solution is a complex task. There are many conflicting drivers and even more possible ‘right’ solutions. Whether the architecture was in fact a good choice usually is not known until many months or even years later, when inevitable changes and additions put the original architecture to test. There is no cookbook for enterprise integration solutions. Most integration vendors provide methodologies and best practices, but these instructions tend to be very much geared towards the vendor-provided tool set and often lack treatment of the bigger picture, including underlying guidelines and principles. As a result, successful enterprise integration architects tend to be few and far in between and have usually acquired their knowledge the hard way. -

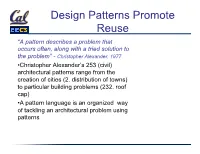

Design Patterns Promote Reuse

Design Patterns Promote Reuse “A pattern describes a problem that occurs often, along with a tried solution to the problem” - Christopher Alexander, 1977 • Christopher Alexander’s 253 (civil) architectural patterns range from the creation of cities (2. distribution of towns) to particular building problems (232. roof cap) • A pattern language is an organized way of tackling an architectural problem using patterns Kinds of Patterns in Software • Architectural (“macroscale”) patterns • Model-view-controller • Pipe & Filter (e.g. compiler, Unix pipeline) • Event-based (e.g. interactive game) • Layering (e.g. SaaS technology stack) • Computation patterns • Fast Fourier transform • Structured & unstructured grids • Dense linear algebra • Sparse linear algebra • GoF (Gang of Four) Patterns: structural, creational, behavior The Gang of Four (GoF) • 23 structural design patterns • description of communicating objects & classes • captures common (and successful) solution to a category of related problem instances • can be customized to solve a specific (new) problem in that category • Pattern ≠ • individual classes or libraries (list, hash, ...) • full design—more like a blueprint for a design The GoF Pattern Zoo 1. Factory 13. Observer 14. Mediator 2. Abstract factory 15. Chain of responsibility 3. Builder Creation 16. Command 4. Prototype 17. Interpreter 18. Iterator 5. Singleton/Null obj 19. Memento (memoization) 6. Adapter Behavioral 20. State 21. Strategy 7. Composite 22. Template 8. Proxy 23. Visitor Structural 9. Bridge 10. Flyweight 11. -

From a Pattern Language to a Field of Centers and Beyond Patterns and Centers, Innovation, Improvisation, and Creativity

From a Pattern Language to a Field of Centers and Beyond Patterns and Centers, Innovation, Improvisation, and Creativity Hajo Neis Illustration 1: University of Oregon in Portland Downtown Urban Campus The Campus is located in downtown Portland in adapted old warehouse buildings, and was first designed in the Oregon pattern language method with the principles of pat- terns and user participation. The White Stag building facilities are open since 2009. 144 Hajo Neis INTRODUCTION What we call now the ›overall pattern language approach‹ in architecture, urban design, and planning has grown from its original principle of ›pattern and pat- tern language‹ into a large and solid body of theory and professional work. To- day, pattern theory and practice includes a large number of principles, methods, techniques and practical project applications in which patterns themselves play a specific part within this larger body of knowledge. Not only has the pattern lan- guage approach grown in its original area of architecture, but it has also (though less triumphantly than silently) expanded into a large number of other disciplines and fields, in particular computer and software science, education, biology, com- munity psychology, and numerous practical fields. Nevertheless, we first have to acknowledge that the pattern approach originally started with a single principle almost 50 years ago, the principle of pattern and pattern language that gave the name to this school of thought and practical professional project work. In this article we want to trace some of the theoretical and practical develop- ment of the pattern method and its realization in practical projects. We want to explore how challenges and opportunities resulted in the adaptation of the pattern language method into various forms of pattern project formats and formulations including ›pattern language‹ and ›project language.‹ We want to look at various forms of innovations and techniques that deal with theoretical improvements as well as the necessities of adaptation for practical cases and projects. -

A Pattern Approach to Interaction Design

A Pattern Approach to Interaction Design Jan O. Borchers Department of Computer Science Darmstadt University of Technology Alexanderstr. 6, 64283 Darmstadt, Germany [email protected] ABSTRACT perts need to work together very closely with team members To create successful interactive systems, user interface de- from other disciplines. Most notably, they need to coop- signers need to cooperate with developers and application erate with application domain experts to identify the con- domain experts in an interdisciplinary team. These groups, cepts, tasks, and terminology of the product environment, however, usually miss a common terminology to exchange and with the development team to make sure the internal ideas, opinions, and values. system design supports the interaction techniques required. This paper presents an approach that uses pattern languages However, these disciplines lack a common language: It is to capture this knowledge in software development, HCI, difficult for the user interface designer to explain his guide- and the application domain. A formal, domain-independent lines and concerns to the other groups. It is often even definition of design patterns allows for computer support more problematic to extract application domain concepts without sacrificing readability, and pattern use is integrated from the user representative in a usable form. And it is into the usability engineering life cycle. hard for HCI people, and for application domain experts even more so, to understand the architectural and techno- As an example, experience from building an award-winning logical constraints and rules that guide the systems engineer interactive music exhibit was turned into a pattern language, in her design process. -

Pattern Languages in HCI: a Critical Review

HUMAN–COMPUTER INTERACTION, 2006, Volume 21, pp. 49–102 Copyright © 2006, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Pattern Languages in HCI: A Critical Review Andy Dearden Sheffield Hallam University Janet Finlay Leeds Metropolitan University ABSTRACT This article presents a critical review of patterns and pattern languages in hu- man–computer interaction (HCI). In recent years, patterns and pattern languages have received considerable attention in HCI for their potential as a means for de- veloping and communicating information and knowledge to support good de- sign. This review examines the background to patterns and pattern languages in HCI, and seeks to locate pattern languages in relation to other approaches to in- teraction design. The review explores four key issues: What is a pattern? What is a pattern language? How are patterns and pattern languages used? and How are values reflected in the pattern-based approach to design? Following on from the review, a future research agenda is proposed for patterns and pattern languages in HCI. Andy Dearden is an interaction designer with an interest in knowledge sharing and communication in software development. He is a senior lecturer in the Com- munication and Computing Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University. Janet Finlay is a usability researcher with an interest in design communication and systems evaluation. She is Professor of Interactive Systems in Innovation North at Leeds Metropolitan University. 50 DEARDEN AND FINLAY CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE SCOPE OF THIS REVIEW 2.1. General Software Design Patterns 2.2. Interface Software Design Patterns 2.3. Interaction Design Patterns 3. A SHORT HISTORY OF PATTERNS 3.1. -

The Origins of Pattern Theory: the Future of the Theory, and the Generation of a Living World

www.computer.org/software The Origins of Pattern Theory: The Future of the Theory, and the Generation of a Living World Christopher Alexander Vol. 16, No. 5 September/October 1999 This material is presented to ensure timely dissemination of scholarly and technical work. Copyright and all rights therein are retained by authors or by other copyright holders. All persons copying this information are expected to adhere to the terms and constraints invoked by each author's copyright. In most cases, these works may not be reposted without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. © 2006 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from the IEEE. For more information, please see www.ieee.org/portal/pages/about/documentation/copyright/polilink.html. THE ORIGINS OF PATTERN THEORY THE FUTURE OF THE THEORY, AND THE GENERATION OF A LIVING WORLD Christopher Alexander Introduction by James O. Coplien nce in a great while, a great idea makes it across the boundary of one discipline to take root in another. The adoption of Christopher O Alexander’s patterns by the software community is one such event. Alexander both commands respect and inspires controversy in his own discipline; he is the author of several books with long-running publication records, the first recipient of the AIA Gold Medal for Research, a member of the Swedish Royal Academy since 1980, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, recipient of dozens of awards and honors including the Best Building in Japan award in 1985, and the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Distinguished Professor Award. -

The Method of Agile Pattern Creation for Campus Building: the Keio-SFC Experiment

The Method of Agile Pattern Creation for Campus Building: The Keio-SFC Experiment TAKASHI IBA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University NORIHIKO KIMURA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University TAKUYA HONDA, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University SUMIRE NAKAMURA, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University SAKURAKO KOGURE, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University AYAKA YOSHIKAWA, Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University In this paper, we address the method and practice of continuously creating pattern language in any phase of designing the campus, as an agile design method involving the campus users. The process of creating pattern language grasps and discloses discoveries and findings in campus planning, enabling all the users to pursue their ideal campus. The patterns that were shaped can be categorized into three domains; architecture and landscape, educational programs, and internal activities for campus planning. This paper also adopts the practical example of the campus planning process of a residential education and research facility, called Student Build Campus SBC), an initiative that allows people to create their own campus at Keio University, Shonan Fujisawa Campus (SFC) in Japan. Our research is based on architect Christopher Alexander’s studies on the Oregon Experiment and the construction of Eishin Campus School. We also present the point in which the process of creating pattern language follows the research studies from the agile design method -

Frontiers of Pattern Language Technology

Frontiers of Pattern Language Technology Pattern Language, 1977 Network of Relationships “We need a web way of thinking.” - Jane Jacobs Herbert Simon, 1962 “The Architecture of Complexity” - nearly decomposable hierarchies (with “panarchic” connections - Holling) Christopher Alexander, 1964-5 “A city is not a tree” – its “overlaps” create clusters, or “patterns,” that can be manipulated more easily (related to Object-Oriented Programming) The surprising existing benefits of Pattern Language technology.... * “Design patterns” used as a widespread computer programming system (Mac OS, iPhone, most games, etc.) * Wiki invented by Ward Cunningham as a direct outgrowth * Direct lineage to Agile, Scrum, Extreme Programming * Pattern languages used in many other fields …. So why have they not been more infuential in the built environment??? Why have pattern languages not been more infuential in the built environment?.... * Theory 1: “Architects are just weird!” (Preference for “starchitecure,” extravagant objects, etc.) * Theory 2: The original book is too “proprietary,” not “open source” enough for extensive development and refinement * Theory 3: The software people, especially, used key strategies to make pattern languages far more useful, leading to an explosion of useful new tools and approaches …. So what can we learn from them??? * Portland, OR. Based NGO with international network of researchers * Executive director is Michael Mehaffy, student and long-time colleague of Christopher Alexander, inter-disciplinary collaborator in philosophy, sciences, public affairs, business and economics, architecture, planning * Board member is Ward Cunningham, one of the pioneers of pattern languages in software, Agile, Scrum etc., and inventor of wiki * Other board members are architects, financial experts, former students of Alexander Custom “Project Pattern Languages” (in conventional paper format) Custom “Project Pattern Languages” create the elements of a “generative code” (e.g.