Pest Risk Analysis for Developing Countries: the Case of Zambia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dickeya Blackleg Is a More Aggressive Disease Than Blackleg Caused by Pectobacterium Atrosepticum

PEI Potato Day 2017 Dickeya is the name of a group of bacteria. Various Dickeya species cause different plant diseases. Two species of Dickeya cause blackleg in potato. Dickeya blackleg is a more aggressive disease than blackleg caused by Pectobacterium atrosepticum. One of the blackleg-causing Dickeya species now occurs in Maine, and has been spread to other states. Blackleg is a potato disease with characteristic symptoms seed-piece decay black-pigmented soft rot of stems soft rot of tubers Blackleg is caused by several bacteria: . Pectobacterium atrosepticum . Pectobacterium brasiliense . Pectobacterium parmentieri (formerly wasabiae) . Dickeya dianthicola . Dickeya solani ATROSEPTICUM BLACKLEG DICKEYA BLACKLEG Usual cause of blackleg in Recently introduced into the Canada – in the past and United States, probably from currently Europe Favours lower temperatures Favours higher temperatures Symptoms: almost always Symptoms: sometimes clearly evident and visible on restricted to internal pith tissue stems of the stem Causes limited yield loss May cause serious disease loss ATROSEPTICUM DICKEYA Blackleg develops from bacteria that move from the seed tuber into the vascular tissue of the stem. These bacteria grow and multiple and produce soft-rotting Drawing from Potato Health Management. R.C. Rowe, ed. enzymes. APS Press Blackleg Disease Cycle The Seed Potato . They may look healthy and well BUT blackleg bacteria may be present in lenticels or stolon end vascular tissue During the growing season — from bacteria that -

Entomology of the Aucklands and Other Islands South of New Zealand: Lepidoptera, Ex Cluding Non-Crambine Pyralidae

Pacific Insects Monograph 27: 55-172 10 November 1971 ENTOMOLOGY OF THE AUCKLANDS AND OTHER ISLANDS SOUTH OF NEW ZEALAND: LEPIDOPTERA, EX CLUDING NON-CRAMBINE PYRALIDAE By J. S. Dugdale1 CONTENTS Introduction 55 Acknowledgements 58 Faunal Composition and Relationships 58 Faunal List 59 Key to Families 68 1. Arctiidae 71 2. Carposinidae 73 Coleophoridae 76 Cosmopterygidae 77 3. Crambinae (pt Pyralidae) 77 4. Elachistidae 79 5. Geometridae 89 Hyponomeutidae 115 6. Nepticulidae 115 7. Noctuidae 117 8. Oecophoridae 131 9. Psychidae 137 10. Pterophoridae 145 11. Tineidae... 148 12. Tortricidae 156 References 169 Note 172 Abstract: This paper deals with all Lepidoptera, excluding the non-crambine Pyralidae, of Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes and Snares Is. The native resident fauna of these islands consists of 42 species of which 21 (50%) are endemic, in 27 genera, of which 3 (11%) are endemic, in 12 families. The endemic fauna is characterised by brachyptery (66%), body size under 10 mm (72%) and concealed, or strictly ground- dwelling larval life. All species can be related to mainland forms; there is a distinctive pre-Pleistocene element as well as some instances of possible Pleistocene introductions, as suggested by the presence of pairs of species, one member of which is endemic but fully winged. A graph and tables are given showing the composition of the fauna, its distribution, habits, and presumed derivations. Host plants or host niches are discussed. An additional 7 species are considered to be non-resident waifs. The taxonomic part includes keys to families (applicable only to the subantarctic fauna), and to genera and species. -

Population Variability of Rotylenchulus Reniformis in Cotton Agroecosystems Megan Leach Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2010 Population Variability of Rotylenchulus reniformis in Cotton Agroecosystems Megan Leach Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Leach, Megan, "Population Variability of Rotylenchulus reniformis in Cotton Agroecosystems" (2010). All Dissertations. 669. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POPULATION VARIABILITY OF ROTYLENCHULUS RENIFORMIS IN COTTON AGROECOSYSTEMS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Plant and Environmental Sciences by Megan Marie Leach December 2010 Accepted by: Dr. Paula Agudelo, Committee Chair Dr. Halina Knap Dr. John Mueller Dr. Amy Lawton-Rauh Dr. Emerson Shipe i ABSTRACT Rotylenchulus reniformis, reniform nematode, is a highly variable species and an economically important pest in many cotton fields across the southeast. Rotation to resistant or poor host crops is a prescribed method for management of reniform nematode. An increase in the incidence and prevalence of the nematode in the United States has been reported over the -

Opening of Symposium 08:50 Professor Lyn Beazley, Chief Scientist of Western Australia Chair – Elaine Davison Chemical Control of Soil-Borne Diseases

The following organisations sponsored this symposium and the Organising Committee and delegates thank them sincerely for their support. Major sponsors Bayer CropScience offers leading brands and expertise in the areas of crop protection, seeds and plant biotechnology, and non-agricultural pest control. With a strong commitment to The Grains Research and Development Corporation is one of the world's leading grains innovation, research and development, we are committed to working together with growers and research organisations, responsible for planning and investing in R & D to support partners along the entire value chain; to cultivate ideas and answers so that Australian effective competition by Australian grain growers in global markets, through enhanced agriculture can be more efficient and more sustainable year on year. For every $10 spent on profitability and sustainability. The GRDC's research portfolio covers 25 leviable crops our products, more than $1 goes towards creating even better products for our customers. We spanning temperate and tropical cereals,oilseeds and pulses, with over $7billion per year innovate together with farmers to bring smart solutions to market, enabling them to grow in gross value of production. Contact GRDC 02 6166 4500 or go to www.grdc.com.au healthier crops, more efficiently and more sustainably." Other sponsors PROGRAM & PAPERS OF THE SEVENTH AUSTRALASIAN SOILBORNE DISEASES SYMPOSIUM 17-20 SEPTEMBER 2012 ISBN: 978-0-646-58584-0 Citation Proceedings of the Seventh Australasian Soilborne Diseases Symposium (Ed. WJ MacLeod) Cover photographs supplied by Daniel Huberli, Andrew Taylor, Tourism Western Australia. Welcome to the Seventh Australasian Soilborne Diseases Symposium The first Australasian Soilborne Diseases Symposium was held on the Gold Coast in 1999, and was followed by successful meetings at Lorne, the Barossa Valley, Christchurch, Thredbo and the Sunshine Coast. -

The Infestation Rate and Abundance of Insect Pests on Stored Corn in Different Climatic Zones of Turkey

Türk. entomol. bült., 2016, 6(4): 349-356 ISSN 2146-975X DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16969/teb.13658 E-ISSN 2536-4928 Original article (Orijinal araştırma) The infestation rate and abundance of insect pests on stored corn in different climatic zones of Turkey Türkiye’nin farklı coğrafi bölgelerinde depolanmış mısırlar üzerinde rastlanan böcek türlerinin bulaşma oranları ve yoğunlukları Ali Arda IŞIKBER1* Hasan TUNAZ1 İnanç DOĞANAY1 Mehmet Kubilay ER1 Summary The occurrence and abundance of insect pests infesting stored-corn in three climatic zones of Turkey (southern (Adana, Mersin and Kahramanmaraş provinces), south-eastern (Şanlıurfa province) and central (Konya province) regions) were studied by taking corn samples from different corn storages in each region every each month from June up to and including November. Seven species, Tribolium castaneum (Herbst), Tribolium confusum Jaquelin du Val., Rhyzopertha dominica (F.), Sitophilus oryzae (L.), Oryzaephilus surinamensis (L.), Cryptolestes ferrugineus (Stephens), and Latheticus oryzae (Waterhouse) belonging to 5 families of Coleoptera were found. The infestation rate of insect species varied with the climatic zones of Turkey. S. oryzae indicated the highest infestation rate (80%) in the central region, followed by T. castaneum (40%) and C. ferrugineus (20%). T. castaneum and C. ferrugineus had the highest infestation rate (28.5%) in the south-eastern region while both T. castaneum and S. oryzae (40%) had the highest infestation rate in the southern region. In southern region, the total number of insects per 1 kg corn grain was 33.8 during sampling dates while it was 2.8 and 11.7 insects per 1 kg corn in central and south-eastern region respectively. -

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

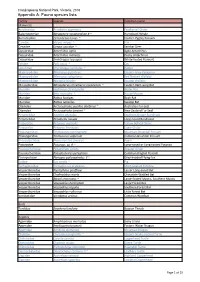

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

Downloaded from BOLD Or Requested from Other Authors

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Towards a global DNA barcode reference library for quarantine identifcations of lepidopteran Received: 28 November 2018 Accepted: 5 April 2019 stemborers, with an emphasis on Published: xx xx xxxx sugarcane pests Timothy R. C. Lee 1, Stacey J. Anderson2, Lucy T. T. Tran-Nguyen3, Nader Sallam4, Bruno P. Le Ru5,6, Desmond Conlong7,8, Kevin Powell 9, Andrew Ward10 & Andrew Mitchell1 Lepidopteran stemborers are among the most damaging agricultural pests worldwide, able to reduce crop yields by up to 40%. Sugarcane is the world’s most prolifc crop, and several stemborer species from the families Noctuidae, Tortricidae, Crambidae and Pyralidae attack sugarcane. Australia is currently free of the most damaging stemborers, but biosecurity eforts are hampered by the difculty in morphologically distinguishing stemborer species. Here we assess the utility of DNA barcoding in identifying stemborer pest species. We review the current state of the COI barcode sequence library for sugarcane stemborers, assembling a dataset of 1297 sequences from 64 species. Sequences were from specimens collected and identifed in this study, downloaded from BOLD or requested from other authors. We performed species delimitation analyses to assess species diversity and the efectiveness of barcoding in this group. Seven species exhibited <0.03 K2P interspecifc diversity, indicating that diagnostic barcoding will work well in most of the studied taxa. We identifed 24 instances of identifcation errors in the online database, which has hampered unambiguous stemborer identifcation using barcodes. Instances of very high within-species diversity indicate that nuclear markers (e.g. 18S, 28S) and additional morphological data (genitalia dissection of all lineages) are needed to confrm species boundaries. -

The Apameini of Israel (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) SHILAP Revista De Lepidopterología, Vol

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Kravchenko, V. D.; Fibiger, M.; Mooser, J.; Junnila, A.; Müller, G. C. The Apameini of Israel (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 36, núm. 142, junio, 2008, pp. 253-259 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45512540015 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative SHILAP Nº 142 9/6/08 11:52 Página 253 SHILAP Revta. lepid., 36 (142), junio 2008: 253-259 CODEN: SRLPEF ISSN:0300-5267 The Apameini of Israel (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) V. D. Kravchenko, M. Fibiger, J. Mooser, A. Junnila & G. C. Müller Abstract In Israel, 20 species of tribe Apameini belonging to 10 genera have been found to date. Four species are endemic of the Levant (Sesamia ilonae, Luperina kravchenkoi, Gortyna gyulaii and Lenisa wiltshirei). Others are mostly Palaearctic, Mediterranean, Iranian and Irano-Turanian elements. Grassland species of the Apameini are mainly associated with the Temperate region and are univoltine with highest rate of occurrence in May, or in autumn. Most wetland and oases species are multivoltine and occur in oases and riverbeds over the country, though few of the species are extremely localized. The S. ilonae is presently known only from northern area of the Sea of Galilee, while A. deserticola is from oases of the Dead Sea area. -

Diversity of Pectobacteriaceae Species in Potato Growing Regions in Northern Morocco

microorganisms Article Diversity of Pectobacteriaceae Species in Potato Growing Regions in Northern Morocco Saïd Oulghazi 1,2, Mohieddine Moumni 1, Slimane Khayi 3 ,Kévin Robic 2,4, Sohaib Sarfraz 5, Céline Lopez-Roques 6,Céline Vandecasteele 6 and Denis Faure 2,* 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Moulay Ismaïl University, 50000 Meknes, Morocco; [email protected] (S.O.); [email protected] (M.M.) 2 Institute for Integrative Biology of the Cell (I2BC), Université Paris-Saclay, CEA, CNRS, 91198 Gif-sur-Yvette, France; [email protected] 3 Biotechnology Research Unit, CRRA-Rabat, National Institut for Agricultural Research (INRA), 10101 Rabat, Morocco; [email protected] 4 National Federation of Seed Potato Growers (FN3PT-RD3PT), 75008 Paris, France 5 Department of Plant Pathology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad Sub-Campus Depalpur, 38000 Okara, Pakistan; [email protected] 6 INRA, US 1426, GeT-PlaGe, Genotoul, 31320 Castanet-Tolosan, France; [email protected] (C.L.-R.); [email protected] (C.V.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 April 2020; Accepted: 9 June 2020; Published: 13 June 2020 Abstract: Dickeya and Pectobacterium pathogens are causative agents of several diseases that affect many crops worldwide. This work investigated the species diversity of these pathogens in Morocco, where Dickeya pathogens have only been isolated from potato fields recently. To this end, samplings were conducted in three major potato growing areas over a three-year period (2015–2017). Pathogens were characterized by sequence determination of both the gapA gene marker and genomes using Illumina and Oxford Nanopore technologies. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

STORGARD Insect Identification Poster

® IPM PARTNER® INSECT IDENTIFICATION GUIDE ® Name Photo Size Color Typical Favorite Attracted Geographic Penetrate Product Recommendation (mm) Life Cycle Food to Light Distribution Packages MOTHS Almond Moth 14-20 Gray 25-30 Dried fruit Yes General Yes, Cadra cautella days and grain larvae only STORGARD® II STORGARD® III CIDETRAK® IMM Also available in QUICK-CHANGE™ Also available in QUICK-CHANGE™ (Mating Disruptant) Angoumois 28-35 Yes, Grain Moth 13-17 Buff days Whole grain Yes General larvae only Sitotroga cerealella STORGARD® II STORGARD® III Casemaking 30-60 Wool, natural Yes, Clothes Moth 11 Brownish days fibers and hair Yes General larvae only Tinea pellionella STORGARD® II STORGARD® III European Grain Moth 13-17 White & 90-300 Grain Yes Northern Yes, Nemapogon granellus brown days larvae only STORGARD® II STORGARD® III Copper Indianmeal Moth Broken or 8-10 red & silver 28-35 processed Yes General Yes, Plodia interpunctella days larvae only gray grain STORGARD® II STORGARD® III CIDETRAK® IMM Also available in QUICK-CHANGE™ Also available in QUICK-CHANGE™ (Mating Disruptant) Mediterranean Gray & Flour and Flour Moth 10-15 30-180 processed Yes General Yes, black days larvae only Ephestia kuehniella cereal grain STORGARD® II STORGARD® III CIDETRAK® IMM Also available in QUICK-CHANGE™ Also available in QUICK-CHANGE™ (Mating Disruptant) Raisin Moth Drying and 12-20 Gray 32 days Yes General Yes, dried fruit larvae only Cadra figulilella STORGARD® II STORGARD® III CIDETRAK® IMM Also available in QUICK-CHANGE™ Also available in QUICK-CHANGE™ -

Monitoring Report Spring/Summer 2015 Contents

Wimbledon and Putney Commons Monitoring Report Spring/Summer 2015 Contents CONTEXT 1 A. SYSTEMATIC RECORDING 3 METHODS 3 OUTCOMES 6 REFLECTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 B. BIOBLITZ 19 REFLECTIONS AND LESSONS LEARNT 21 C. REFERENCES 22 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1 Location of The Plain on Wimbledon and Putney Commons 2 Figure 2 Experimental Reptile Refuge near the Junction of Centre Path and Somerset Ride 5 Figure 3 Contrasting Cut and Uncut Areas in the Conservation Zone of The Plain, Spring 2015 6/7 Figure 4 Notable Plant Species Recorded on The Plain, Summer 2015 8 Figure 5 Meadow Brown and white Admiral Butterflies 14 Figure 6 Hairy Dragonfly and Willow Emerald Damselfly 14 Figure 7 The BioBlitz Route 15 Figure 8 Vestal and European Corn-borer moths 16 LIST OF TABLES Table 1 Mowing Dates for the Conservation Area of The Plain 3 Table 2 Dates for General Observational Records of The Plain, 2015 10 Table 3 Birds of The Plain, Spring - Summer 2015 11 Table 4 Summary of Insect Recording in 2015 12/13 Table 5 Rare Beetles Living in the Vicinity of The Plain 15 LIST OF APPENDICES A1 The Wildlife and Conservation Forum and Volunteer Recorders 23 A2 Sward Height Data Spring 2015 24 A3 Floral Records for The Plain : Wimbledon and Putney Commons 2015 26 A4 The Plain Spring and Summer 2015 – John Weir’s General Reports 30 A5 a Birds on The Plain March to September 2015; 41 B Birds on The Plain - summary of frequencies 42 A6 ai Butterflies on The Plain (DW) 43 aii Butterfly long-term transect including The Plain (SR) 44 aiii New woodland butterfly transect