Theunsung Synagogues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Burnet Tuthill Collection

WILLIAM BURNET TUTHILL COLLECTION William Burnet Tuthill Collection Guide Overview: Repository: Inclusive Dates: Carnegie Hall Archives – 1891 - 1920 Storage Room Creator: Extent: William Burnet Tuthill 1 box, 42 folders; 1 Scrapbook (10 X 15 X 3.5), 5 pages + 1 folder; 44 architectural drawings Summary / Abstract: William Burnet Tuthill is the architect of Carnegie Hall. He was an amateur cellist, the secretary of the Oratorio Society, and an active man in the music panorama of New York. The Collection includes the questionnaires he sent to European theaters to investigate about other theaters and hall, a scrapbook with clippings of articles and lithographs of his works, and a series of architectural drawings for the Hall and its renovations. Access and restriction: This collection is open to on-site access. Appointments must be made with Carnegie Hall Archives. Due to the fragile nature of the Scrapbook, consultation could be restricted by archivist’s choice. To publish images of material from this collection, permission must be obtained in writing from the Carnegie Hall Archives Collection Identifier & Preferred citation note: CHA – WBTC – Q (001-042) ; CHA – WBTC – S (001-011) ; CHA – AD (001-044) William Burnet Tuthill Collection, Personal Collections, Carnegie Hall Archives, NY Biography of William Burnet Tuthill William Burnet Tuthill born in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1855. He was a professional architect as well as passionate and amateur musician, a good cellist, and an active man in the music scene of New York. He studied at College of the City of New York in 1875 and after receiving the Master of Arts degree, started his architectural career in Richard Morris Hunt’s atelier (renowned architect recognized for the main hall and the façade of the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth Avenue, the Charity Home on Amsterdam Avenue – now the Hosteling International Building- and the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty). -

Elevator Interior Design

C AMB RIDGE A select portfolio of architectural mesh projects for new or refurbished elevator cabs, lobbies and high-traffic spaces featuring Cambridge’s metal mesh. ARCHITECTURAL MESH Beautiful, light-weight and durable, architectural mesh has been prized by architects and designers since we first wove metal fabric for the elevator cabs in Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in 1958. And it’s still there today. Learn more about our elite line of elegant panels in stainless steel, brass, copper and aluminum. Carnegie Hall, New York City Elegant burnished aluminum panels lift Carnegie Hall’s elevator interiors to another level. Installed by EDI/ECI in concert with Iu + Biblowicz Architects, Comcast Center, Philadelphia, PA Cambridge’s Sawgrass pattern adds When designing the a refined and resilient interior to world’s tallest green this refurbished masterpiece. building, Robert A.M. © Gbphoto27 | Dreamstime.com Stern Architects added style and sustainability with Empire State Building, Cambridge mesh. New York City Classically outfitted Beyer, Blinder & with the chic Ritz pattern, the flexible Belle Architects stainless steel fabric integrates the modernized the lobby and elevators with a smooth landmark and seamless design. skyscraper’s elevator cabs with Cambridge’s Stipple mesh. Installed by the National Elevator Cab & Door Co., the dappled brushed aluminum surface stands up to the traffic and traditions of this legendary building. Victory Plaza, Dallas, TX TFO Architecture’s YAHOO!, Sunnyvale, CA expansive mixed-use project in the center Gensler architects of downtown selected Cambridge’s incorporates one of Silk mesh to clad Cambridge’s most elevators at Yahoo’s popular rigid mesh Silicon Valley fabrics. -

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

Cororio Carnegie Hall / New York City Tour May 22 – 26, 2018

CoroRio Carnegie Hall / New York City Tour May 22 – 26, 2018 Round Trip Airfare from Memphis to New York City (pricing updated 9/10/17) Round Trip Ground Transportation to/from Airport and Hotel in New York City PERFORMANCE with DCINY at Carnegie Hall (performers)** Four Nights’ Accommodations at a Midtown Manhattan Hotel** Three Group Dinners ~ Two Sightseeing Attractions ~ One Broadway Show ~ One 4-Trip Metro Card** Orchestra Level Concert Seating and POST CONCERT RECEPTION for all Performers and VIP Patrons** All taxes, gratuities and mandatory fees** **Inclusions in the Land only package Prices are per person DCINY Registration Type** Quad Triple Double Single Air & Land Performer $ 2015.00 $ 2140.00 $ 2385.00 $ 3020.00 Air & Land VIP Patron (Non-Performer) $ 1520.00 $ 1645.00 $ 1890.00 $ 2525.00 Air & Land Concert Attendee $ 1205.00 $ 1330.00 $ 1575.00 $ 2210.00 Land Only Performer $ 1665.00 $ 1790.00 $ 2035.00 $ 2670.00 Land Only VIP Patron (Non-Performer) $ 1170.00 $ 1295.00 $ 1540.00 $ 2175.00 Land Only Concert Attendee $ 855.00 $ 980.00 $ 1225.00 $ 1860.00 **DCINY Registration Inclusions: All students are required to purchase the Performer package. VIP Patrons are admitted to all rehearsals, including dress rehearsals in Carnegie Hall, and receive orchestra level concert seating and admission to the post concert reception for all performers & directors. Parents who are accompanying their singer are encouraged to be VIP Patrons (at least one per family). Concert attendee cost includes $80 for an orchestra level concert seat with the rest of the group. Note: The above prices include DCINY Performer Fee of $790.00 and DCINY VIP fee of $395.00, all hotel taxes, mandatory baggage handling fee at hotel (one suitcase per person), gratuities and service charges. -

Introduction

Introduction Forty Years with the Jews of Harlem— the Old and the Renewed In the spring of 2002, David Dunlap, architecture columnist for the New York Times, came to my office to discuss an article he was com- posing about a lost and forgotten Jewish community. The subject of his investigation was Harlem. I was taken aback by the idea that a New York Jewish settlement that once had housed close to 175,000 Jews was not remembered. After all, I had written my first book, When Harlem Was Jewish, 1870– 1930, in 1978. And for more than the next quarter century, I had reminded everyone who would hear me out— fellow academicians and the general public alike— how important the com- munity had been in the history of Gotham. I argued everywhere that the saga of immigrant Jewish life and advancement in the metropolis during the early decades of the prior century was incomplete without considering Harlem. One of the prime intellectual conceits was that a complex set of forces motivated Jewish relocation from one area of the city to the next and greatly influenced the types of group identifica- tions that were maintained. Prior historians had not been sensitive to the reality that downtown—that is, the Lower East Side—and uptown alike were home, at least after 1900, to both poor and more affluent Jews. Previous scholars also had not discussed how these two sibling communities likewise included both acculturated Jews and those who were just starting to learn American ways. Indeed, the fact was that more immigrants and their children moved to Harlem, or were pushed out of the so-called “ghetto,” before they achieved financial success than as a sign that they had begun to make it in America. -

Conference P14 Art P3 Wellness P8 2 AUGUST 21, 2019 • MANHATTAN TIMES • in Living Color Hese Walls Do Speak

AUGUST 21 - AUGUST 27, 2019 • VOL. 20 • No. 33 WASHINGTON HEIGHTS • INWOOD • HARLEM • EAST HARLEM NORTHERN MANHATTAN’S BILINGUAL NEWSPAPER EL PERIODICO BILINGUE DEL NORTE DE MANHATTAN NOW EVERY WEDNESDAY TODOS LOS MIERCOLES Hailing Hartman p7 Canto de Hartman p7 Photo: Gregg McQueen Conference p14 Art p3 Wellness p8 2 AUGUST 21, 2019 • MANHATTAN TIMES • www.manhattantimesnews.com In Living Color hese walls do speak. Ray “Sting Ray” Rodríguez dubbed the concrete walls of the now Jackie Robinson T The Graffiti Hall of Fame (GHOF) Educational Complex’s schoolyard the started in the El Barrio section of East “GHOF,” and it has been attracting some of Harlem, at a playground on the corner of the best street artists in the world for more 106th Street and Park Avenue. than 30 years. It was a local meet up for graffiti writers Much of the contemporary street art from around the city as a place to hang out origins began within the GHOF’s four walls, An artist touches up his piece. and exchange tales of subway bombing runs and the pieces there reflect the vision of many VASE, SPHERE, NOVER, PHETUS, (painting expeditions). The walls of the pioneers who laid the foundation to mural art. opportunity for artists around the globe to CHRISRWK, HEK TAD, SHIRO, MODUS, playground served as a safe haven to practice As the face of the city changes, GHOF come and paint. DONTAY TC5, AND OTHERS and test new skills and forge relationships. supporters have continued to host an annual Among those expected this weekend on Looking to formally establish this place event at which fans gather to celebrate the art August 24th and 25th to participate are TATS For more information and tickets, where graffiti artists could hone their craft form, its history and its artists. -

Carnegie Hall Subscription Exchange Form

Subscription Exchange Exchange 1 Account Number Name Enclosed please find the following ticket(s) for exchange: Address Concert City State Zip Date Number of Tickets Value Phone (Daytime) Please send me exchange ticket(s) for the following*: Email First Choice Seating Requests If I cannot be seated in the same seat category as the ticket(s) I am Second Choice returning, I will accept the following (please check all that apply): Third Choice Stern/Perelman Zankel Blavatnik Family First Tier Parterre / Parterre Box Prime Parquet / Parquet Mezzanine / Mezzanine Box Second Tier Exchange 2 Weill Dress Circle Orchestra Center Balcony / Balcony Balcony Enclosed please find the following ticket(s) for exchange: Obstructed View / Restricted Leg Room Best available seating Concert Payment Please charge (or credit) any price difference to my credit card. Date Number of Tickets Value Mastercard American Express Discover Visa Please send me exchange ticket(s) for the following*: Account Number Expiration Date First Choice Second Choice Name (as it appears on card) Third Choice Signature Billing Address (if different from address above) Exchange 3 Exchange Procedure Enclosed please find the following ticket(s) for exchange: Complete this form and mail it to the address listed below with the tickets you wish to exchange. As an alternative, you may tear the tickets Concert in half, and email a scan or photo of them along with this form. To allow time for Carnegie Hall to resell your original seats, we request that ticket exchanges be received at least two business days (Monday Date Number of Tickets Value through Friday) before the event date of the tickets being exchanged. -

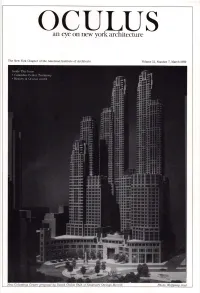

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

Departmentof Parks

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS BOROUGH OF THE BRONX CITY OF NEW YORK JOSEPH P. HENNESSY, Commissioner HERALD SQUARE PRESS NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH OF 'I'HE BRONX January 30, 1922. Hon. John F. Hylan, Mayor, City of New York. Sir : I submit herewith annual report of the Department of Parks, Borough of The Bronx, for 1921. Respect fully, ANNUAL REPORT-1921 In submitting to your Honor the report of the operations of this depart- ment for 1921, the last year of the first term of your administration, it will . not be out of place to review or refer briefly to some of the most important things accomplished by this department, or that this department was asso- ciated with during the past 4 years. The very first problem presented involved matters connected with the appropriation for temporary use to the Navy Department of 225 acres in Pelham Bay Park for a Naval Station for war purposes, in addition to the 235 acres for which a permit was given late in 1917. A total of 481 one- story buildings of various kinds were erected during 1918, equipped with heating and lighting systems. This camp contained at one time as many as 20,000 men, who came and went constantly. AH roads leading to the camp were park roads and in view of the heavy trucking had to be constantly under inspection and repair. The Navy De- partment took over the pedestrian walk from City Island Bridge to City Island Road, but constructed another cement walk 12 feet wide and 5,500 feet long, at the request of this department, at an expenditure of $20,000. -

9–18–09 Vol. 74 No. 180 Friday Sept. 18, 2009 Pages 47871–47998

9–18–09 Friday Vol. 74 No. 180 Sept. 18, 2009 Pages 47871–47998 VerDate Nov 24 2008 17:36 Sep 17, 2009 Jkt 217001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\18SEWS.LOC 18SEWS mstockstill on DSKH9S0YB1PROD with FEDREGWS II Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 180 / Friday, September 18, 2009 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records PUBLIC Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man.