Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

Remembering Robert Venturi, a Modern Mannerist

The Plan Journal 4 (1): 253-259, 2019 doi: 10.15274/tpj.2019.04.01.1 Remembering Robert Venturi, a Modern Mannerist In Memoriam / THEORY Maurizio Sabini After the generation of the “founders” of the Modern Movement, very few architects had the same impact that Robert Venturi had on architecture and the way we understand it in our post-modern era. Aptly so and with a virtually universal consensus, Vincent Scully called Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) “probably the most important writing on the making of architecture since Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture, of 1923.” 1 And I would submit that no other book has had an equally consequential impact ever since, even though Learning from Las Vegas (published by Venturi with Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour in 1972) has come quite close. As Aaron Betsky has observed: Like the Modernism that Venturi sought to nuance and enrich, many of the elements for which he argued were present in even the most reduced forms of high Modernism. Venturi was trying to save Modernism from its own pronouncements more than from its practices. To a large extent, he won, to the point now that we cannot think of architecture since 1966 without reference to Robert Venturi.2 253 The Plan Journal 4 (1): 253-259, 2019 - doi: 10.15274/tpj.2019.04.01.1 www.theplanjournal.com Figure 1. Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (London: The Architectural Press, with the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1977; or. ed., New York: The Museum of Art, 1966). -

The Suppression of Jewish Culture by the Soviet Union's Emigration

\\server05\productn\B\BIN\23-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-JUL-05 11:26 A STRUGGLE TO PRESERVE ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE SUPPRESSION OF JEWISH CULTURE BY THE SOVIET UNION’S EMIGRATION POLICY BETWEEN 1945-1985 I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR .................. 159 R II. BEFORE THE BORDERS WERE CLOSED: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER STALIN (1945-1947) ......... 163 R III. CLOSING OF THE BORDER: CESSATION OF JEWISH EMIGRATION UNDER STALIN’S REGIME .................... 166 R IV. THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER KHRUSHCHEV AND BREZHNEV .................... 168 R V. CONCLUSION .............................................. 174 R I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR Despite undergoing numerous revisions, neither the Soviet Constitu- tion nor the Soviet Criminal Code ever adopted any laws or regulations that openly or implicitly permitted persecution of or discrimination against members of any minority group.1 On the surface, the laws were always structured to promote and protect equality of rights and status for more than one hundred different ethnic groups. Since November 15, 1917, a resolution issued by the Second All-Russia Congress of the Sovi- ets called for the “revoking of all and every national and national-relig- ious privilege and restriction.”2 The Congress also expressly recognized “the right of the peoples of Russia to free self-determination up to seces- sion and the formation of an independent state.” Identical resolutions were later adopted by each of the 15 Soviet Republics. Furthermore, Article 124 of the 1936 (Stalin-revised) Constitution stated that “[f]reedom of religious worship and freedom of anti-religious propaganda is recognized for all citizens.” 3 1 See generally W.E. -

The Synagogue in Corsicana, Texas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SFA ScholarWorks East Texas Historical Journal Volume 28 | Issue 2 Article 6 10-1990 The yS nagogue in Corsicana, Texas Jane Manaster Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Manaster, Jane (1990) "The yS nagogue in Corsicana, Texas," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 28: Iss. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol28/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 16 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE SYNAGOGUE IN CORSICANA, TEXAS by Jane Manasta The cultural landscape of Texas continually yields examples of architectural form elements derived directly from Europe. Distinctive Ger man, Polish, Alsatian, Russian, and Irish vernacular structures have been documented, reflecting the diverse human settlement of the state. l Added to the well-known introduction of folk styles from the Southern United States and Mexico, these exotic buildings help lend regional character to different parts of Texas. Previous research has focused largely upon dwellings, and the potential contributions of many ethnic groups have not been examined. Attention in the present study is turned toward vernacular ecclesiastical architecture and to the small-town Jewish population of East Texas. Folk architecture has been identified in churches standing in those rural towns, especially in the central part of the state, that look like nineteenth-century time warps overlaid with a modern American veneer of pick-up trucks, franchised fast-food stops, and gas stations. -

Allen Memorial Art Museum Teacher Resource Packet - AMAM 1977 Addition

Allen Memorial Art Museum Teacher Resource Packet - AMAM 1977 Addition Robert Venturi (American, 1925 – 2018) Allen Memorial Art Museum Addition¸ 1977 Sandstone façade, glass, brick. Robert Venturi was an American architect born in 1925. Best known for being an innovator of postmodern architecture, he and his wife Denise Scott Brown worked on a number of notable museum projects including the 1977 Oberlin addition, the Seattle Museum of Art, and the Sainsbury addition to the National Gallery in London. His architecture is characterized by a sensitive and thoughtful attempt to reconcile the work to its surroundings and function. Biography Robert Venturi was born in 1925 in Philadelphia, PA, and was considered to be one of the foremost postmodern architects of his time. He attended Princeton University in the 1940s, graduating in 1950 summa cum laude. His early experiences were under Eero Saarinen, who designed the famous Gateway Arch in St. Louis, and Louis Kahn, famous for his museum design at the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas and at Yale University. The AMAM addition represents one of Venturi’s first forays into museum design, and was intended to serve as a functional addition to increase gallery and classroom space. Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College For Educational Use Only 1 Venturi was also very well known for his theoretical work in architecture, including Complexity and Contradictions in Architecture (1966), and Learning from Las Vegas (1972). The second book presented the idea of the “decorated shed” and the “duck” as opposing forms of architecture. The Vanna Venturi house was designed for Venturi’s mother in Philadelphia, and is considered one of his masterworks. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

The Hebrew-Jewish Disconnection

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Master’s Theses and Projects College of Graduate Studies 5-2016 The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection Jacey Peers Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses Part of the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Peers, Jacey. (2016). The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection. In BSU Master’s Theses and Projects. Item 32. Available at http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses/32 Copyright © 2016 Jacey Peers This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. THE HEBREW-JEWISH DISCONNECTION Submitted by Jacey Peers Department of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Bridgewater State University Spring 2016 Content and Style Approved By: ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Joyce Rain Anderson, Chair of Thesis Committee Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Anne Doyle, Committee Member Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Julia (Yulia) Stakhnevich, Committee Member Date 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my mom for her support throughout all of my academic endeavors; even when she was only half listening, she was always there for me. I truly could not have done any of this without you. To my dad, who converted to Judaism at 56, thank you for showing me that being Jewish is more than having a certain blood that runs through your veins, and that there is hope for me to feel like I belong in the community I was born into, but have always felt next to. -

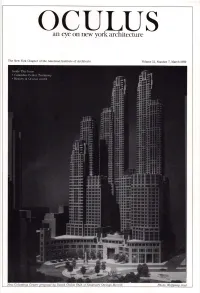

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

Courtesy of Theyood Family TABLE of CONTENTS

Courtesy of TheYood Family TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 MIGRATIONS 4 Daniel Soyer: Goldene Medine, Treyfene Medine: Judaism Survives Migration to America 5 Deborah Dash Moore: The Meanings of Migration: American Jews, Eldridge Street and Neighborhoods 9 PRACTICE 13 Riv-Ellen Prell: A Culture of Order: Decorum and the Eldridge Street Synagogue 14 Jeffrey Gurock: Closing the Americanization Gap between the Eldridge Street Synagogue’s Leaders 19 and Downtown’s Rabbis ENCOUNTERS 23 Jeffrey Shandler: A Tale of Two Cantors: Pinhas Minkowski and Yosele Rosenblatt 24 Tony Michels: The Jewish Ghetto Meets its Neighbors 29 PRESERVATION 34 Samuel Gruber: The Choices We Make: The Eldridge Street Synagogue and Historic Preservation 35 Marilyn Chiat: Saving and Praising the Past 40 MUSEUM AT ELDRIDGE STREET | ACADEMICANGLES 3 he Eldridge Street Synagogue is a National Historic Landmark, the first major house of worship built by East European Jews in America. When it opened in September of 1887 it was an experiment, a response to the immigrants’desire to practice Orthodox Judaism, and to do so in America, their new Promised Land. Today the Eldridge Street Synagogue is Tthe only building on the Lower East Side—once the largest Jewish city in the world—earmarked for broad and public exploration of the American Jewish experience. The Museum at Eldridge Street researches the history of the building, uncovering new ways and stories to bring the building and its history to life. Learning about the congregants and their history ties us to broader trends on the Lower East Side and in American history. To help explore these trends, the Museum at Eldridge Street asks leading scholars to lend their expertise. -

Seven to Receive Honorary Degrees UM Sweeps CASE Awards

VERITAFor the Faculty and Staff of the University of Mi: March-April 1997 VolumSe 39 Number 6 Seven to receive honorary degrees oted architects Denise Scott sy-nthesis of nucleic acids. He is the Bethune-Cookman College and Florida affiliated with a number of the great Brown and Robert Venturi. a recipient of numerous other awards, Memorial College, chairman emeritus medical institutions in the United Nhusband-wife team, will be including the Max Berg Award for Pro of the United Protestant Appeal, and States, including Cornell Medical Col honored at this year's Commencement longing Human Life and the Scientific vice president of the Black Archives lege, the Mayo Clinic, and the Univer on May- 9, along with a host of famous Achievement Award of the American Research Foundation. Among his many- sity of Pittsburgh. His books and achievers including Sarah Caldwell; Medical Association. honors are the Greater Miami Urban teachings have influenced the way mil William H. Gray III; a\rthur Romberg; Garth C. Reeves, reporter, editor, League's Distinguished Service Award, lions of children were raised. Garth C. Reeves, Sr.; and Benjamin publisher, banker, entrepreneur, and the American Jew-ish Committee's Robert Venturi. a Philadelphia McLane Spock. In addition to receiving community activist, attended Dade Human Relations Award, the Boy- native, graduated from Princeton Uni an honorary- doctorate. Reeves will County Public Schools and received Scouts Silver Beaver award and the Sil versity. His firm. Venturi, Scott Brown deliver the Commencement address. his bachelor's degree from Florida ver Medallion of the National Confer and Associates, Inc., has made its mark Denise Scott Brow-n, a principal A&M College. -

Studiomagazine164.Pdf

�������������������������� ארכיטקטורה סטודיו Studio 164 164 אפריל≠מאי April-May 2006 2006 גיליון ארכיטקטורה מיוחד Special Architecture Issue עורכים: צבי אלחייני, יעל ברגשטיין Editors: Zvi Elhyani, Yael Bergstein רחוב אחוזת בית Ahuzat Bayit St. 4 4 ת.ד. 29772, תל–אביב POB 29772, Tel-Aviv 61290 61290 טל: 5165274≠03, פקס: Tel: 972-3-5165274, Fax: 972-3-5165694 03≠5165694 www.studiomagazine.co.il www.studiomagazine.co.il [email protected] מערכת והפקה Editor in Chief Yael Bergstein Design Ankati [email protected] Text Editing Einat Adi ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� מודעות Architecture Editor Zvi Elhyani ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ Production Manager Nitzan Wolansky [email protected] �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Advertising Manager Rachel Michaeli ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� עורכת ראשית יעל ברגשטיין Advertisment -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel