Re-Writing the Genetic Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESG Report Viacomcbs 2019

ACTIONEnvironmental, Social, and Governance Report ViacomCBS 2019 Introduction Governance On-screen Workforce Sustainable Reporting content and and culture production indices social impact and operations Contents Introduction 3 CEO letter 4 Our approach to ESG 6 About ViacomCBS 9 About this report 10 Our material topics 11 Case study: Responding to a global pandemic 12 Aligning with the UN Sustainable Development Goals 15 Governance 17 ESG governance 19 Corporate governance 20 Data privacy and security 22 Public policy engagement 23 On-screen content and social impact 24 Diverse and inclusive content 26 Responsible content and advertising 31 Using our content platforms for good 33 Expanding our social impact through community projects 35 Workforce and culture 38 A culture of diversity and inclusion 40 Preventing harassment and discrimination 45 Employee attraction, retention, and training 46 Health, safety, and security 48 Labor relations 50 Sustainable production, and operations 51 Climate change 53 Sustainable production 58 Environmental impacts of our operations and facilities 60 Supply chain responsibility 63 Consumer products 66 Reporting indices 68 GRI Index 69 SASB Index 81 COVER IMAGES (FROM LEFT TO RIGHT): CBS, NCIS; CBS Sports; CBS, Super Bowl LIII; CBS News, CBS This Morning ViacomCBS ESG Report 2019 Introduction Governance On-screen Workforce Sustainable Reporting content and and culture production indices social impact and operations Introduction Welcome to our first ESG Report, Action: ESG at ViacomCBS. As we unleash the -

CBS National Agreement

(510) AGREEMENT BETWEEN CBS BROADCASTING INC. AND INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF ELECTRICAL WORKERS February 1, 2018 – April 30, 2021 CBS/IBEW National Agreement INDEX Page PREAMBLE ..........................................................................................................................1 BASIC PRINCIPLES ............................................................................................................1 ARTICLE I ............................................................................................................................2 Section 1.01 – Term ...............................................................................................................2 Section 1.02 – Recognition and Scope ..................................................................................2 Section 1.03 – Work Jurisdiction ...........................................................................................2 Section 1.04 – Territorial Jurisdiction ...................................................................................14 Section 1.05 – Subcontracting & Contracting Out ................................................................16 Section 1.06 – Employment & Union Membership ...............................................................16 Section 1.07 – No Strike or Lockout .....................................................................................18 Section 1.08 – No Discrimination ..........................................................................................19 ARTICLE II -

TELEVISION and VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997: a Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1

ISBN: 0-8444-0946-4 [Note: This is a PDF version of the report, converted from an ASCII text version. It lacks footnote text and some of the tables. For more information, please contact Steve Leggett via email at "[email protected]"] TELEVISION AND VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997 A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1 October 1997 REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS TELEVISION AND VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997 A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1: Report Library of Congress Washington, D.C. October 1997 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Television and video preservation 1997: A report on the current state of American television and video preservation: report of the Librarian of Congress. p. cm. þThis report was written by William T. Murphy, assigned to the Library of Congress under an inter-agency agreement with the National Archives and Records Administration, effective October 1, 1995 to November 15, 1996"--T.p. verso. þSeptember 1997." Contents: v. 1. Report - ISBN 0-8444-0946-4 1. Television film--Preservation--United States. 2. Video tapes--Preservation--United States. I. Murphy, William Thomas II. Library of Congress. TR886.3 .T45 1997 778.59'7'0973--dc 21 97-31530 CIP Table of Contents List of Figures . Acknowledgements. Preface by James H. Billington, The Librarian of Congress . Executive Summary . 1. Introduction A. Origins of Study . B. Scope of Study . C. Fact-finding Process . D. Urgency. E. Earlier Efforts to Preserve Television . F. Major Issues . 2. The Materials and Their Preservation Needs A. -

Your Guide to Ebu Services

YOUR GUIDE TO EBU SERVICES 1 The European Broadcasting Union (EBU) is the world’s foremost alliance of public service media (PSM). Our mission is to make PSM indispensable. We have 115 Member organizations in 56 countries in Europe, and an additional 31 Associates in Asia, Australasia, Africa and the Americas. Our Members operate almost 2,000 television, radio and online channels and services and offer a wealth of content across other platforms. Together, they reach audiences of more than one billion people around the world, broadcasting in almost 160 languages. We are one EBU with two distinct fields of activity: Member Services and Business Services. Our Member Services strive to secure a sustainable future for public service media, provide our Members with a centre for learning and sharing, and build on our founding ethos of solidarity and cooperation to provide an exchange of world-class news, sports news, and music. Our Business Services, operating as Eurovision Services, are the media industry’s premier distributor and producer of high-quality live news, sport and entertainment with over 70,000 transmissions and 100,000 hours of news and sport every year. We return the profits of Business Services to the organization for the benefit of Members. 2 2 WELCOME TO THE EBU! As a Member, you are part of a unique community of media organizations from 56 countries that together provide a powerful voice championing and upholding the values of PSM. We are a network of like-minded people that not only share the same ideals but come together to share knowledge, ideas and inspiration. -

United Technologies / Viacom Letter Re

233503 April 21,2005 via Federal Express Mr. Brad W. Bradley EPA Project Coordinator U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region V, Mailcode SR-6J 77 W. Jackson Boulevard Chicago, IL 60604 W Re: In the Matter of Little Mississinewa Site CERCLA Docket No. V-W-'05-C-812 Dear Mr. Bradley: I. Introduction On or about April 4, 2005, the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region V ("EPA"), issued an Administrative Order for Remedial Action (Docket No. V-W-'05-C-812) (the "Order" or "Unilateral Order") to Viacom Inc. ("Viacom") and United Technologies Corporation on behalf of Lear Corporation Automotive Systems ("UTC") (collectively, "Respondents"), directing those parties to implement the approved remedial design for the Little Mississinewa Site in Union , City, Indiana (the "Site"). The purposes of this letter are: (1) to advise EPA, pursuant to Section XXIV of the Order, of Respondents' intention to comply with the terms of the Order to the extent such compliance is required under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act ("CERCLA"), 42 U.S.C. §§9601, et seq., and its implementing regulations, namely the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan ("NCP"), 40 C.F.R. Part 300; and (2) to outline several objections and defenses that Respondents have to the Order, as issued. II. General Objections and Reservation of Rights As an initial matter, it should be noted that by setting forth any objections or defenses in this letter, or by submitting this letter at all, Respondents do not waive, and hereby specifically reserve their rights to raise additional or different objections and defenses to the Order at some later time, or to provide additional information and evidence in support of any position that they may respectively or collectively take in Mr. -

The CBS Writers Mentoring Program

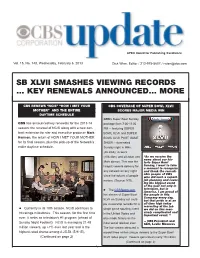

APEX Award for Publishing Excellence Vol. 15, No. 748, Wednesday, February 6, 2013 Dick Wien, Editor / 212-975-5607 / [email protected] SB XLVII SMASHES VIEWING RECORDS ... KEY RENEWALS ANNOUNCED... MORE CBS RENEWS “NCIS” “HOW I MET YOUR CBS COVERAGE OF SUPER BOWL XLVII MOTHER” AND THE ENTIRE SCORES MAJOR MEDIA WIN DAYTIME SCHEDULE CBS's Super Bowl Sunday CBS has announced key renewals for the 2013-14 package from 7:00-11:00 season: the renewal of NCIS along with a new con- PM -- featuring SUPER tract extension for star and executive producer Mark BOWL XLVII and SUPER Harmon, the return of HOW I MET YOUR MOTHER BOWL XLVII POST GAME for its final season, plus the pick-up of the Network’s SHOW -- dominated entire daytime schedule. Sunday night in HHs (46.2/68), viewers (108.48m) and all Adult and “As we receive the news about our his- Male demos. This was the toric Super Bowl largest viewers delivery for Sunday, I want to take a moment to recognize any network on any night and thank the remark- able people of CBS since the advent of people who did such a superb meters. (Source: NTI). job planning and cover- ing the biggest event of the year not only in The CBSSports.com television, but in America. I am proud of live stream of Super Bowl the people in this Company every day, XLVII on Sunday set multi- but that pride is at an ple viewership records for a all-time high today marveling at the job Currently in its 10th season, NCIS continues to single game sporting event we did on this mas- hit ratings milestones. -

Report: Empire State Film Production Tax Credit Report

Appendix I: New York State Qualified Production Facilities Appendix I: New York State Qualified Production Facilities Page I-1 05/17/10 Qualified Production Facilities Note: this list is does not claim to be comprehensive or final. If you have a question about a facility that is not on this list, contact the state and/or city film offices. NEW YORK CITY QUALIFIED FACILITIES: These facilities qualify for both New York State and New York City tax credits. All Mobile Video Chelsea (26th Street) – Nova, Mike Green, Joann (212) 727-1234 AMV Unitel (57th & 53rd) – Ron Ranieri 212-265-3600 (57th st. AMV) 212-246-5040 (53rd street AMV) 221 W 26th Street (main office) New York, NY 10001 [email protected] www.allmobilevideo.com 221 W. 26th Street Studio A 98’x89’x40’ (19’ to grid) Studio B 80’x65’x27’ (19’ to grid) Studio C 40’x52’x20’ (14.5’ to grid) Studio D 21’x30’x20’ (14.5’ to grid) 515 W 57th Street Studio A 101’6’ x 47’6’ x 23’ (19’ to grid) (flexible) 53rd Street Studio 53 (5,370 SF) Mickey Broadway Stages Dawn Dianda (718) 349-9146 203 Meserole Ave (main office) Brooklyn, NY 11222 www.broadway-stages.com 775 Humboldt St Brooklyn, NY Stage 3: 50 x 150 x 16 (10,000 SF) 280 Calyer Street Greenpoint Brooklyn, NY Stage 4: 75 x 100 (7,500 SF) Stage 5: 50 x 100 (5,000 SF) Stage 6: 75 x 100 (7,500 SF) Stage 7: 100 x 100 (10,000 SF) Stage 8: 100 x 100 (10,000 SF) Stage 10:100 x 175 x 30 (17,500 SF) Page 1 of 13 05/17/10 259 Green Street Greenpoint, Brooklyn, NY Stage D: 160 x 50 (8,000 SF) 370 Green Point Avenue Greenpoint, Brooklyn, NY Stage -

Books for You: an Annotated Booklist for Senior High. NCTE Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 454 525 CS 217 591 AUTHOR Beers, Kylene, Ed.; Lesesne, Teri S., Ed. TITLE Books for You: An Annotated Booklist for Senior High. Fourteenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0372-3 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 439p.; Produced with the Committee on the Senior High School Booklist, NCTE. Foreword by Michael Cart. For the 13th edition, see ED 415 506. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03723: $24.95 members; $34.95 nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC18 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; High School Students; High Schools; Independent Reading; Mass Media; *Nonfiction; Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; Recreational Reading IDENTIFIERS Information Books; Multicultural Materials; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Beginning with a history of young adult literature and ending with a history of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) "Books for You" booklist project, this fourteenth edition collection offers high school students, teachers, and librarians a comprehensive annotated list of more than a thousand books published between 1997 and 1999. Whether adventure, detailed how-to, helpful study guide for the SAT, historical account, biography, or fantasy, readers will find much to engage with and think about in the collection. In thematically arranged chapters, readers can explore through brief entries that include bibliographic information and informative summaries. -

Viacomcbs Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-09553 ViacomCBS Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 1515 Broadway New York, New York 10036 (212) 258-6000 (Address, including zip code, and telephone numbers, including area code, of registrant’s principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Trading Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Symbols Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.001 par value VIACA The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC Class B Common Stock, $0.001 par value VIAC The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer (as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933). Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Fiscal Year 2020 Annual Report on Form 10-K

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE ☒ SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE ☐ SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-09553 ViacomCBS Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 1515 Broadway New York, New York 10036 (212) 258-6000 (Address, including zip code, and telephone numbers, including area code, of registrant’s principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Trading Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Symbols Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.001 par value VIACA The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC Class B Common Stock, $0.001 par value VIAC The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer (as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933). Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Bice C. Wilson, Aia

BICE C. WILSON, AIA Office: 914-288-5431 Mobile: 917-319-3512 [email protected] AREAS OF EXPERTISE: Project Management | Architecture | Pre-design Services | Architectural Programming | Real Estate Search, Due Diligence & Related Negotiations | Interior Design | Codes & Zoning | Urban Design PROJECT TYPES: Workplace design | Broadcast Workplaces | Adaptive Reuse | Community Revitalization | Single and Multi-Family Housing CHARACTERISTICS: o Both practical & visionary o A strong leader & mentor o Able to find the most elegant design & management solutions for a given challenge ARCHITECTURAL LICENSES: New York Massachusetts New Jersey Maryland Connecticut Michigan Pennsylvania NCARB EDUCATION: Bachelor of Architecture – Pratt Institute EMPLOYMENT: § Principal at Studio Bice Architecture PLLC 2012 to Present o Corporate Interiors project design and project management services Bice C. Wilson, AIA CV & Representative Projects [email protected] 917.319.3512 o Pre-design and project management services for various mixed use development projects. § Principal at Syndicate Architecture PLLC 2014 to 2017 o Assisted clients with several complex real estate transactions for landmark and mixed use developments. o Design and Project Management for several workplace interiors projects. § A Founding Principal of Meridian Design Associates, Architects, PC – 1981 thru 2014 o Managing Partner, led the firm to $3,000,000 in revenues and 25 employees. o Led the Urban Design and Residential Development Practice. o 1996 AIA Urban Design Award of Excellence for Mianus Bioregional Planning Project, which was also exhibited at the Cooper Hewitt Museum o Internationally known expert in the Media & Communications / Creative Workplace o Design and project management experience in mission critical projects on fast track schedules o Pre-design & due diligence services credited with saving clients millions of dollars in making real estate deals. -

"The History of NBC New York Television Studios, 1935-1956"

`1 | P a g e "The History of NBC New York Television Studios, 1935-1956" Volume 1 of 2 (Revised) 5 Rare Interior Photos of The International Theater added on page 64 By Bobby Ellerbee And Eyes Of A Generation.com Preface and Acknowledgement This is the first known chronological listing that details the conversions of NBC’s Radio City studios at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City. Also included in this exclusive presentation by and for Eyes Of A Generation, are the outside performance theaters and their conversion dates to NBC Television theaters. This compilation gives us the clearest and most concise guide yet to the production and technical operations of television’s early days and the network that pioneered so much of the new medium. As you will see, many shows were done as “remotes” in NBC radio studios with in-house mobile camera units, and predate the official conversion date which signifies the studio now has its own control room and stage lighting. Eyes Of A Generation would like to offer a huge thanks to the many past and present NBC people that helped, but most especially to Frank Merklein (NBC 1947-1961) Joel Spector (NBC 1965-2001), Dennis Degan (NBC 2003 to present), historian David Schwartz (GSN) and Gady Reinhold (CBS 1966 to present), for their first hand knowledge, photos and help. This presentation is presented as a public service by the world’s ultimate destination for television history…The Eyes Of A Generation. –Bobby Ellerbee http://www.eyesofageneration.com/ https://www.facebook.com/pages/Eyes-Of-A-Generationcom/189359747768249 `2 | P a g e "The History of NBC New York Television Studios, 1935-1956" Volume 1 of 2 Contents Please Note: Converted should be understood as the debut date of the facility as an exclusive TV studio, now equipped with its own control room.