In Praise of Diversity: a Resource Book for Multicultural Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

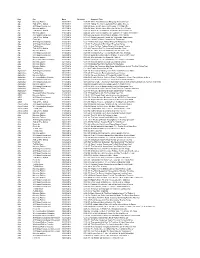

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union's

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union’s East Border Brie, Mircea and Horga, Ioan and Şipoş, Sorin University of Oradea, Romania 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/44082/ MPRA Paper No. 44082, posted 31 Jan 2013 05:28 UTC ETHNICITY, CONFESSION AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE AT THE EUROPEAN UNION EASTERN BORDER ETHNICITY, CONFESSION AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE AT THE EUROPEAN UNION EASTERN BORDER Mircea BRIE Ioan HORGA Sorin ŞIPOŞ (Coordinators) Debrecen/Oradea 2011 This present volume contains the papers of the international conference Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union‟s East Border, held in Oradea between 2nd-5th of June 2011, organized by Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea-Debrecen, University of Oradea and Department of International Relations and European Studies, with the support of the European Commission and Bihor County Council. CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY STUDIES Mircea BRIE Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Dialogue in the European Border Space.......11 Ioan HORGA Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Education in the Curricula of European Studies .......19 MINORITY AND MAJORITY IN THE EASTERN EUROPEAN AREA Victoria BEVZIUC Electoral Systems and Minorities Representations in the Eastern European Area........31 Sergiu CORNEA, Valentina CORNEA Administrative Tools in the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Ethnic Minorities .............................................................................................................47 -

The Role of Shared Historical Memory in Israeli and Polish Education Systems. Issues and Trends

Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Humanitas. Pedagogika, ss. 273-293 Oryginalny artykuł naukowy Original article Data wpływu/Received: 16.02.2019 Data recenzji/Accepted: 26.04.2019 Data publikacji/Published: 10.06.2019 Źródła finansowania publikacji: Ariel University DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0013.2311 Authors’ Contribution: (A) Study Design (projekt badania) (B) Data Collection (zbieranie danych) (C) Statistical Analysis (analiza statystyczna) (D) Data Interpretation (interpretacja danych) (E) Manuscript Preparation (redagowanie opracowania) (F) Literature Search (badania literaturowe) Nitza Davidovitch* Eyal Levin** THE ROLE OF SHARED HISTORICAL MEMORY IN ISRAELI AND POLISH EDUCATION SYSTEMS. ISSUES AND TRENDS INTRODUCTION n February 1, 2018, despite Israeli and American criticism, Poland’s Sen- Oate approved a highly controversial bill that bans any Holocaust accusations against Poles as well as descriptions of Nazi death camps as Polish. The law essentially bans accusations that some Poles were complicit in the Nazi crimes committed on Polish soil, including the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. Once the leg- islation was signed into law, about a fortnight later, by Polish President Andrzej Duda, anyone convicted under the law could face fines or up to three years in jail. Critics of the bill, including the US State Department and Israeli officials, feared that it would infringe upon free speech and could even be used to target Holocaust survivors or historians. In Israel, the reaction was fierce. “One cannot change history, * ORCID: 0000-0001-7273-903X. Ariel University in Izrael. ** ORCID: 0000-0001-5461-6634. Ariel University in Izrael. ZN_20_2019_POL.indb 273 05.06.2019 14:08:14 274 Nitza Davidovitch, Eyal Levin and the Holocaust cannot be denied,” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated. -

Peregrination in the Age of the Numerus Clausus: Hungarian

DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2019.10 PEREGRINATION IN THE AGE OF THE NUMERUS CLAUSUS: HUNGARIAN JEWISH STUDENTS IN INTERWAR EUROPE Ágnes Katalin Kelemen A DISSERTATION In History Presented to the Faculties of the Central European University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Budapest, Hungary 2019 Supervisors Victor Karády CEU eTD Collection Michael Laurence Miller DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2019.10 Copyright in the text of this dissertation rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European University Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions and no materials previously written and/or published by another person unless otherwise noted. CEU eTD Collection II DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2019.10 Abstract This dissertation investigates the dynamics between academic antisemitism, Jewish social mobility and Jewish migration through the case study of the “numerus clausus exiles” – as Jewish students who left interwar Hungary due to the antisemitic numerus clausus law (Law XXV of 1920) were called by contemporaries and historians. After a conceptual and historiographic introduction in the first chapter embedding this work in the contexts of Jewish studies, social history and exile studies; interwar Hungarian Jewish peregrination is examined from four different aspects in four chapters based on four different types of sources. -

Legacy, Vol. 17, 2017

2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship A Publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta A Publication of the Sigma Kappa & the Southern Illinois University Carbondale History Department & the Southern Illinois University Volume 17 Volume LEGACY • A Journal of Student Scholarship • Volume 17 • 2017 LEGACY Volume 17 2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship Editorial Staff Denise Diliberto Geoff Lybeck Gray Whaley Faculty Editor Hale Yılmaz The editorial staff would like to thank all those who supported this issue of Legacy, especially the SIU Undergradute Student Government, Phi Alpha Theta, SIU Department of History faculty and staff, our history alumni, our department chair Dr. Jonathan Wiesen, the students who submitted papers, and their faculty mentors Professors Jo Ann Argersinger, Jonathan Bean, José Najar, Joseph Sramek and Hale Yılmaz. A publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta & the History Department Southern Illinois University Carbondale history.siu.edu © 2017 Department of History, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved LEGACY Volume 17 2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship Table of Contents The Effects of Collegiate Gay Straight Alliances in the 1980s and 1990s Alicia Mayen ....................................................................................... 1 Students in the Carbondale, Illinois Civil Rights Movement Bryan Jenks ...................................................................................... 15 The Crisis of Legitimacy: Resistance, Unity, and the Stamp Act of 1765, -

Cultural Geography

This document was produced by the Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et An electronic version of this document is available on the Ministère’s Web du Sport. site at: www.mels.gouv.qc.ca Coordination and content Direction de la formation générale des jeunes © Gouvernement du Québec Coordination of production and publishing Ministère de l'Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport, 2014 Direction des communications ISBN 978-2-550-70960-2 (PDF) Title of original document ISBN 978-2-550-70961-9 (French, PDF) Géographie culturelle Legal Deposit – Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2014 English translation Direction de la communauté anglophone — Services langagiers Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport For additional information, contact: General Information Direction des communications Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport 1035, rue De La Chevrotière, 28 e étage Québec (Québec) G1R 5A5 Telephone: 418-643-7095 Toll-free: 1-866-747-6626 14-00181 Table of Contents Cultural Geography Introduction to the Cultural Geography Program . 1 Program Content . 14 Contribution of the Cultural Geography Program to Prescribed Elements of the Program Content . 15 Students' Education . 1 Designated focus . 16 Nature of the Program . 1 Objects of learning . 16 How the Competencies Work Together . 1 Concepts . 16 Knowledge related to the geography of the cultural areas . 16 From the Elementary Level to Secondary Cycle Two . 3 Other Resources for Helping Students Develop the Competencies . 16 Cultural Areas . 17 Making Connections: Cultural Geography and the Other African Cultural Area . 18 Dimensions of the Québec Education Program . 4 Arab Cultural Area . -

Old Heads Tell Their Stories: from Street Gangs to Street Organizations in New York City

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 305 UD 031 930 AUTHOR Brotherton, David C. TITLE Old Heads Tell Their Stories: From Street Gangs to Street Organizations in New York City. SPONS AGENCY Spencer Foundation, Chicago, IL. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 35p. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adults; *Delinquency; Illegal Drug Use; *Juvenile Gangs; *Leadership; Neighborhoods; Role Models; Urban Areas; *Urban Youth IDENTIFIERS *New York (New York); Street Crime ABSTRACT It has been the contention of researchers that the "old heads" (identified by Anderson in 1990 and Wilson in 1987) of the ghettos and barrios of America have voluntarily or involuntarily left the community, leaving behind new generations of youth without adult role models and legitimate social controllers. This absence of an adult strata of significant others adds one more dynamic to the process of social disorganization and social pathology in the inner city. In New York City, however, a different phenomenon was found. Older men (and women) in their thirties and forties who were participants in the "jacket gangs" of the 1970s and/or the drug gangs of the 1980s are still active on the streets as advisors, mentors, and members of the new street organizations that have replaced the gangs. Through life history interviews with 20 "old heads," this paper traces the development of New York City's urban working-class street cultures from corner gangs to drug gangs to street organizations. It also offers a critical assessment of the state of gang theory. Analysis of the development of street organizations in New York goes beyond this study, and would have to include the importance of street-prison social support systems, the marginalization of poor barrio and ghetto youth, the influence of politicized "old heads," the nature of the illicit economy, the qualitative nonviolent evolution of street subcultures, and the changing role of women in the new subculture. -

The Global Irish and Chinese: Migration, Exclusion, and Foreign Relations Among Empires, 1784-1904

THE GLOBAL IRISH AND CHINESE: MIGRATION, EXCLUSION, AND FOREIGN RELATIONS AMONG EMPIRES, 1784-1904 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Barry Patrick McCarron, M.A. Washington, DC April 6, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Barry Patrick McCarron All Rights Reserved ii THE GLOBAL IRISH AND CHINESE: MIGRATION, EXCLUSION, AND FOREIGN RELATIONS AMONG EMPIRES, 1784-1904 Barry Patrick McCarron, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Carol A. Benedict, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation is the first study to examine the Irish and Chinese interethnic and interracial dynamic in the United States and the British Empire in Australia and Canada during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Utilizing comparative and transnational perspectives and drawing on multinational and multilingual archival research including Chinese language sources, “The Global Irish and Chinese” argues that Irish immigrants were at the forefront of anti-Chinese movements in Australia, Canada, and the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century. Their rhetoric and actions gave rise to Chinese immigration restriction legislation and caused major friction in the Qing Empire’s foreign relations with the United States and the British Empire. Moreover, Irish immigrants east and west of the Rocky Mountains and on both sides of the Canada-United States border were central to the formation of a transnational white working-class alliance aimed at restricting the flow of Chinese labor into North America. Looking at the intersections of race, class, ethnicity, and gender, this project reveals a complicated history of relations between the Irish and Chinese in Australia, Canada, and the United States, which began in earnest with the mid-nineteenth century gold rushes in California, New South Wales, Victoria, and British Columbia. -

Louis Rosenberg and the Origins of the Socio-Demographic Study of Jews in Canada

Louis Rosenberg and the Origins of the Socio-Demographic Study of Jews in Canada Morton Wemfeld. * Louis Rosenberg's Canada's Jews: A Social and Economic Study of the Jews in Canada, published in 1939, was a pioneering if unfortunately neglected classic of Canadian ethnic demography and sociology. Its republication in a new edition in 1993, by McGill-Queen's Press, has particular relevance for the community of social scientists devoted to the study of Diaspora Jewish communities, using socio demographic data. Canada's Jews has persisting value as a superb quantitative social history of Canadian Jews in the 1930s. It also is in many ways an unmatched prototype of a study of the ethnic demography of any Canadian minority group. Louis Rosenberg's work was a product of his personal biography, the current socio-political context, and the customs and norms of his discipline. This is the case for those carrying on his work. What follows is a brief and far from exhaustive treatment of the man, the times, and the work. The Man Louis Rosenberg was born in Gonenz, Poland, in 1893. His family was shaped by traditional and secular elements of Jewish culture in Eastern Europe at the turn of the century. When he was three his parents emigrated to England from Lithuania, settling in Leeds, Yorkshire, which had at the time an estimated 12,000 Jews. (Rosenberg, 1968). While his parents spoke Yiddish at home, Rosenberg's language of choice was English; he learned to speak Yiddish fluently only after arriving in Canada. Rosenberg graduated from elementary school in Leeds, won a scholarship for secondary school, and later a scholarship tenable at Leeds University. -

And Mention of American Indians

Updated: December 2020 CHAPTER 7 - THE AMERICAN BAHÁ'Í MAGAZINE January 1970: 1) NABOHR: Past, Present, and Future. The North American Bahá'í Office for Human Rights was established in January 1986. It is reported here that this office sponsored conferences for action on Human Rights in 20 leading cities and on a Canadian Reserve. There is a Photo here of presenter giving the address at the "American Indian and Human Rights" conference in Gallup, New Mexico. p. 3. 2) A program illustration entitled; "A World View" and it includes an Indian image. p. 7. February 1970: checked March 1970: 1) Bahá'í Education Conference Draws Overflow Attendance. More than 500 Bahá'ís from all over the U.S. come to this event. The only non Bahá'í speaker at the conference, Mrs. De Lee has a long record of civil rights activity in South Carolina. Her current project was to help 300 Indian school children in Dorchester County get into the public school. They were considered to be white until they tried to get their children in the public schools there. They were told they couldn't go to the public schools. A Freedom school was set up in an Indian community to teach Indian children and Mrs. Lee is still working towards getting them into the public school. pp. 1, 5. 2) News Briefs: The Minorities Teaching Committee of Albuquerque, NM held a unity Feast recently concurrent with the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which is significant to the Mexican and American Indian populations of the area. -

PDF Download Intercultural Communication for Global

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION FOR GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Regina Williams Davis | 9781465277664 | | | | | Intercultural Communication for Global Engagement 1st edition PDF Book Resilience, on the other hand, includes having an internal locus of control, persistence, tolerance for ambiguity, and resourcefulness. This textbook is suitable for the following courses: Communication and Intercultural Communication. Along with these attributes, verbal communication is also accompanied with non-verbal cues. Create lists, bibliographies and reviews: or. Linked Data More info about Linked Data. A critical analysis of intercultural communication in engineering education". Cross-cultural business communication is very helpful in building cultural intelligence through coaching and training in cross-cultural communication management and facilitation, cross-cultural negotiation, multicultural conflict resolution, customer service, business and organizational communication. September Lewis Value personal and cultural. Inquiry, as the first step of the Intercultural Praxis Model, is an overall interest in learning about and understanding individuals with different cultural backgrounds and world- views, while challenging one's own perceptions. Need assistance in supplementing your quizzes and tests? However, when the receiver of the message is a person from a different culture, the receiver uses information from his or her culture to interpret the message. Acculturation Cultural appropriation Cultural area Cultural artifact Cultural