The Poetry of Things Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interactive Multimedia Solutions Developed for the Opening of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre

Interactive Multimedia Solutions Developed for the Opening of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre Nikolay Borisov, Artem Smolin, Denis Stolyarov, Pavel Shcherbakov St. Petersburg National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics, Saint Petersburg State University Abstract. This paper focuses on teamwork by the National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics (NRU ITMO) and the Aleksandrinsky Theatre in preparation of opening of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre. The Russian State Pushkin Academy Drama Theatre, also known as the Alexandrinsky Theatre, is the oldest national theatre in Rus- sia. Many famous Russian actors performed on the Alexandrinsky’s stage and many great directors. May 2013 marked the opening of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre. The theatre complex comprises three buildings: the new stages building, a media center, and the building housing a center of theatre ed- ucation. Several plays shown simultaneously on multiple stages within the new complex’s buildings constituted the opening gala of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre. The works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky were the plays’ uni- fying theme. NRU ITMO employees developed several interactive theatre pro- ject solutions implemented for the opening of the Alexandrinsky Theatre’s New Stage. Keywords: Theatre, Multimedia, Information Technologies, NRU ITMO, SPbGU 1 Introduction The Russian State Pushkin Academy Drama Theatre, also known as the Alexandrinsky Theatre, is the oldest national theatre in Russia. It was founded in 1756 by the Senate’s decree. The history of the Alexandrinsky Theatre is closely linked to some of the most prominent exponents of Russian culture. -

Bolton High Gets

MemorisI Dsy ’89 will sperk memories of brave men, women By Nancy Concelman It s a time for reflection on what our country Kowalski was aboard the U.S. Navy ship that ,52-piece group. Manchester Herald .stands for,” Osella said. brought MacArthur back to the Philippines in He and his crewmates helped lead the first While Osella is quietly remembering veterans Those who turn out Monday for Manchester’s 194.5, three years after the Japanese victory over American bombing raid over Tokyo in April 1942 who have .survived, those who have died and those Memorial Day parade will see Parade Marshal American and Filipino forces. by bringing planes within 400 feet of the Tokyo who cannot be found to this day. World War II will Ronald Osella looking snappy in his dress U.S. The USS Nashville was MacArthur’s flagship coast. be remembered in a quiet cemetery off Cider Mill three times during the war. Kowalski said. It was Army Reserve uniform, proudly leading “ We pulled the operation off,” Kowalski said. Road in Andover as veteran William Kowalski marchers and waving at friends. Kowalski's home for part of his eight-year Navy "W e sank two Japane.se ships.” tells his story. career. But Osella. a major in the reserves, will be Kowalski will be one of many speakers, young A Kowalski, 72. was among those who helped Gen A ship’s tailor. Kowalski "sewed and pressed thinking about something other than the bands and old. who will remind citizens in area towns Douglas MacArthur keep his famous promi.se, " I for 1,200 men" and helped start the IR-piece USS CARS and the crowds. -

The Russian Theatre After Stalin

The Russian theatre after Stalin Anatoly Smeliansky translated by Patrick Miles published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011–4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Original Russian script © Anatoly Smeliansky 1999 English translation © Cambridge University Press 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in English by Cambridge University Press 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in 9.25/14 pt Trump Medieval [gc] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0521 58235 0 hardback isbn 0521 58794 8 paperback Contents List of plates ix Foreword xi laurence senelick Preface xix Chronology xxiii Biographical notes xxviii Translator’s note xxxviii 1 The Thaw (1953–1968) 1 The mythology of socialist realism 1 Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky initiate a new Soviet theatre 9 The rise and fall of the Sovremennik Theatre 16 Yury Lyubimov and the birth of the Taganka Theatre 30 Where we came from: Tovstonogov’s diagnosis 46 Within the bounds of tenderness (Efros in the sixties) 58 2 The Frosts (1968–1985) 74 Oleg -

By Zukhra Kasimova Submitted to Central European University Department of History Supervisor

ILKHOM IN TASHKENT: FROM KOMSOMOL-INSPIRED STUDIO TO POST-SOVIET INDEPENDENT THEATER By Zukhra Kasimova Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Charles Shaw Second Reader: Professor Marsha Siefert CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection 1 ABSTRACT This thesis aims to research the creation of Ilkhom as an experimental theatre studio under Komsomol Youth League and Theatre Society in the late Brezhnev era in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbek SSR. The research focuses on the controversies of the aims and objectives of these two patronage organizations, which provided an experimental studio with a greater freedom in choice of repertoire and allowed to obtain the status of one of the first non-government theaters on the territory of former Soviet Union. The research is based on the reevaluation of late- Soviet/early post-Soviet period in Uzbekistan through the repertoire of Ilkhom as an independent theatre-studio. The sources used include articles about theatre from republican and all-union press. CEU eTD Collection 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to my research advisor, Professor Charles Shaw, for encouraging me to focus on Soviet theatre developments in Central Asia, as well as for his guidance and tremendous support throughout the research process. -

World Scenography World Scenography

WORLD SCENOGRAPHYWORLD This is the first volume in a new series of books members, it draws together theatre production professionals from looking at significant stage design throughout the around the world for mutual learning and benefit. its working world since 1975. this volume, documenting 1975-1990, has commissions are in the areas of scenography, theatre technology, been about four years in the making, and has had contributions publications and communication, history and theory, education, from 100s of people in over 70 countries. Despite this range of and architecture. both of the editors have worked for many years input, it is not possible for it to be encyclopædic, much as the to benefit theatre professionals internationally, through their editors would like. Neither is the series a collection of “greatest activities in OiStAt. hits,” despite the presence of many of the greatest designs of c the period being examined. instead, the object is to present Peter M Kinnon and Eric Fielding probably met each other at the designs that made a difference, designs that mattered, designs banff School of Fine Arts in the early 1980s, when Peter was on of influence. the current editors plan to do two more volumes faculty and Eric was taking Josef Svoboda’s master class there. documenting 1990-2005 and 2005-2015. they then hope that Neither of them remembers the other. they first worked together others will pick up the torch and prepare subsequent volumes in 1993 when Eric was the general editor of the OiStAt lexicon, each decade thereafter. new Theatre Words, and Peter was an English editor. -

Soviet Cinema of the Sixties

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Articles Arts and Sciences 2018 The Unknown New Wave: Soviet Cinema of the Sixties Alexander V. Prokhorov College of William & Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/aspubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Prokhorov, Alexander V., The Unknown New Wave: Soviet Cinema of the Sixties (2018). Cinema of the Thaw retrospective. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/aspubs/873 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 22 de mai a 3 de jun CINEMA 1 e A CAIXA é uma empresa pública brasileira que prima pelo respeito à diversidade, e mantém comitês internos atuantes para promover entre os seus empregados campanhas, programas e ações voltados para disseminar ideias, conhecimentos e atitudes de respeito e tolerância à diversidade de gênero, raça, orientação sexual e todas as demais diferenças que caracterizam a sociedade. A CAIXA também é uma das principais patrocinadoras da cultura brasileira, e destina, anualmente, mais de R$ 80 milhões de seu orçamento para patrocínio a projetos nas suas unidades da CAIXA Cultural além de outros espaços, com ênfase para exposições, peças de teatro, espetáculos de dança, shows, cinema, festivais de teatro e dança e artesanato brasileiro. Os projetos patrocinados são selecionados via edital público, uma opção da CAIXA para tornar mais democrática e acessível a participação de produtores e artistas de todo o país. -

Katalog Web.Pdf

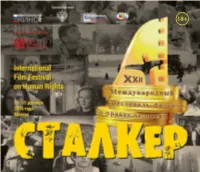

Генеральный партнер: Партнеры: 10–15 декабря 2016 года, Москва ОРГАНИЗАТОРЫ ФЕСТИВАЛЯ FESTIVAL ORGANIZERS ГИЛЬДИЯ КИНОРЕЖИССЕРОВ РОССИИ THE FILM DIRECTORS GUILD OF RUSSIA МИНИСТЕРСТВО КУЛЬТУРЫ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ MINISTRY OF CULTURE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION СОЮЗ ЖУРНАЛИСТОВ РОССИИ RUSSIAN UNION OF JOURNALISTS Генеральный партнер Фестиваля General partner of the Festival ФОНД МИХАИЛА ПРОХОРОВА MIKHAIL PROKHOROV FOUNDATION СОВМЕСТНАЯ ПРОГРАММА РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ JOINT RUSSIA-OHCHR PROJECTS UNDER И УПРАВЛЕНИЯ ВЕРХОВНОГО КОМИССАРА THE FRAMEWORK FOR COOPERATION ПО ПРАВАМ ЧЕЛОВЕКА (УВКПЧ ООН) УПРАВЛЕНИЕ ВЕРХОВНОГО КОМИССАРА ООН UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER ПО ДЕЛАМ БЕЖЕНЦЕВ (УВКБ ООН) FOR REFUGEES (UNHCR) ПРОГРАММНЫЙ ОФИС СОВЕТА ЕВРОПЫ В РФ COUNCIL OF EUROPE PROGRAMME OFFICE IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ПОСОЛЬСТВО КОРОЛЕВСТВА НИДЕРЛАНДОВ В РФ EMBASSY OF THE KINGDOM OF THE NETHERLANDS TO THE RF ПОСОЛЬСТВО КАНАДЫ В РФ EMBASSY OF CANADA IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION БЮРО МЕЖДУНАРОДНОЙ ОРГАНИЗАЦИИ BUREAU OF THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION ПО МИГРАЦИИ (МОМ) В МОСКВЕ FOR MIGRATION (IOM) IN MOSCOW МОСКОВСКАЯ ГИЛЬДИЯ АКТЕРОВ ТЕАТРА И КИНО THE MOSCOW GUILD OF THEATRE AND CINEMA ACTORS Уважаемые друзья! Dear friends! Искренне рад приветствовать участников и гостей XXII Международного фести- I am genially glad to greet the participants and guests of the XXII International Film валя фильмов о правах человека «Сталкер»! Festival on Human Rights “Stalker”! Язык кино понятен и знаком каждому. Регулярно проводящийся фестиваль The language of cinema is known and clear to everyone. Regularly held festival “Stalk- «Сталкер» является одним из наиболее ярких событий общественно-культурной er” is one of the brightest events in Moscow social and cultural life. It has long become жизни Москвы и давно стал уникальной возможностью говорить о правах чело- a unique opportunity to speak about human rights in understandable for wide viewer audi- века на доступном для широкой зрительской аудитории языке. -

Proquest Dissertations

Conceiving American Chekhov: Nikos Psacharopoulos and the Williamstown Theatre Festival Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Yarnelle, David Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 01:08:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/291967 CONCEIVING AMERICAN CHEKHOV: NIKOS PSACHAROPOULOS AND THE WILLIAMSTOWN THEATRE FESTIVAL By David Allan Yamelle Copyright © David Allan Yamelle 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF THEATRE ARTS In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2003 UMI Number: 1414237 Copyright 2003 by Yarnelle, David Allan All rights reserved. UMI UMI Microform 1414237 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fiilfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript m whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. -

The Translations of Brian Friel, Translations and Dancing at Lughnasa

Between Words and Meaning The translations of Brian Friel, Translations and Dancing at Lughnasa A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Cassandra M. F. Fusco University of Canterbury 1998 "Gan cuimhne, duramar aris agus aris eile, nil aon phrionsabal i ndochas" (Ricoeur) I gcuimhne ar m' athair agus ar mo mhathair agus Mira. Is iomai duine a bhfuil me faoi chomaoin aige as an gcuidiu a tugadh dom, ag cur an trachtais seo Ie cMile. Sa gcead ait, ta me faoi chomaoin ag mo thuismitheoiri, a dtiolacaim an staidear seo doibh, ag teaghlach mo bhreithe, idir mharbh agus bheo, go hairithe ag Edward agus Jacqueline, ag m'fhear ceile agus ag ar gc1ann fein, agus John Goodliffe, agus sgolair Gordon Spence. Uathasan, agus 0 mo chairde sa da leathsfear, d'fhoghlaim me tabhacht na cumarsaide, bainte amach go minic Ie stro, tri litreacha lena mbearnai dosheacanta. 'Is iontach an marc a d'fh:ig an comhfhreagras ar mo shaol agus ar mo chuid staideir. Ta me faoi chomaoin, freisin, ag obair Bhrain Ui Fhrighil - focas mo chuid staideir -, ag an fhear fein agus ag a chomhleacaithe a thug freagrai chomh morchroioch sin dom ar na ceisteanna 0 na fritiortha. Is beag duine a ainmnitear anseo ach, mar is leir on trachtas fein, on leabharliosta agus 0 na notai buiochais, chuidigh a Ian daoine liom. Beannaim d' achan duine agaibh, gabhaim buiochas libh agus iarraim pardun oraibh as aon easpa, biodh si ina easpa phearsanta no acaduil, mar nil baint aici leis an muinin, an trua na an ionrachas a thaispeanann sibh, ach cuireann :ir n-easpai i gcuimhne duinn nach foirfe riamh an duine, ach oiread leis an tsamhlaiocht, agus nach mor do coinneailleis ar a aistear. -

Мудрость Внутреннего Голоса Wisdom of Inner Voice

ХРОНОГРАФ CHRONOGRAPH Мудрость внутреннего голоса Анна ЧЕПУРНОВА СчаСтливое СвойСтво великих – умение почувСтвовать Своё призвание и Следовать ему в Самых неподходящих для этого обСтоятельСтвах. Многие Считали, что АлиСа Коонен губит Себя, покидая ХудожеСтвенный театр ради работы С малоизвеСтным тогда режиссёром АлекСандром Таировым. От Студии Евгения вахтангова тоже не ждали оСобого уСпеха. А пятиклассника олега Ефремова, в СталинСкие годы заявившего в школе, что у него будет Свой театр, учительница и вовСе не поняла: «ты хочешь быть артиСтом?» ДейСтвительно, о каком «Своём» театре могла идти речь в конце 1930‑х в СССр? Но прошло время – и окружающие убедилиСь в правоте Коонен, Вахтангова 24.09.1782 09.10.1859 03.11.1866 235 лет назад 158 лет назад 151 год назад и ефремова, которые шли против течения. КОМЕДИЯ «НЕДОРОСЛЬ» АЛЕКСАНДР ОСТРОВСКИЙ РОДИЛАСЬ АЛЕКСАНДРА ВПЕРВЫЕ ПОКАЗАНА ЗАВЕРШИЛ ДРАМУ «ГРОЗА» ЯБЛОЧКИНА НА СЦЕНЕ В ВОЛЬНОМ isdom of nner oice РОССИЙСКОМ ТЕАТРЕ Над этой пьесой драматург Её родителями были актёры W i V работал около трёх Александр и Серафима Anna CHEPURNOVA Денис Фонвизин закончил месяцев. Созданию «Грозы» Яблочкины. В первый раз писать «Недоросля» предшествовало путешествие на сцену девочка вышла в начале 1782 года. Цензоры Островского по Волге, в шесть лет в спектакле, THE HAPPY QUALITY OF THE GREAT IS THE ABILITY TO SEE THEIR VOCATION в петербургских и московских во время которого он имел поставленном приятелем её and follow it under the most unsuitable circumstances. Many people театрах не сразу приняли возможность наблюдать отца. Неудивительно, что, эту остросатирическую пьесу. за бытом и характерами став взрослой, Александра BELIEVED THAT ALICE KOONEN WAS RUINING HERSELF BY LEAVING THE ART Автор добивался её постановки русской провинции. -

Vsevolod Meyerhold

111 VSEVOLOD MEYERHOLD 111 0111 1 111 Routledge Performance Practitioners is a series of introductory guides to the key theatre-makers of the last century. Each volume 111 explains the background to and the work of one of the major influences on twentieth- and twenty-first-century performance. 0111 These compact, well-illustrated and clearly written books will un- ravel the contribution of modern theatre’s most charismatic innovators. Vsevolod Meyerhold is the first book to combine: • a biographical introduction to Meyerhold’s life • a clear explanation of his theoretical writings • an analysis of his masterpiece production Revisor, or The Government Inspector • a comprehensive and usable description of the ‘biomechanical’ exercises he developed for training the actor. 0111 As a first step towards critical understanding, and as an initial explora- tion before going on to further, primary research, Routledge Per- formance Practitioners are unbeatable value for today’s student. Jonathan Pitches is a Principal Lecturer in Performing Arts at Manchester Metropolitan University. He has taught Russian acting tech- niques, including biomechanics, for many years and has written extensively on Russian theatre and the relationship between training 911 and performance. ROUTLEDGE PERFORMANCE PRACTITIONERS Series editor: Franc Chamberlain, University College Northampton Routledge Performance Practitioners is an innovative series of intro- ductory handbooks on key figures in twentieth-century performance practice. Each volume focuses on a theatre-maker whose practical and theoretical work has in some way transformed the way we understand theatre and performance. The books are carefully structured to enable the reader to gain a good grasp of the fundamental elements under- pinning each practitioner’s work. -

Iti-Info” № 3 (24) 2014

RUSSIAN NATIONAL CENTRE OF THE INTERNATIONAL THEATRE INSTITUTE «МИТ-ИНФО» № 3 (24) 2014 “ITI-INFO” № 3 (24) 2014 УЧРЕЖДЁН НЕКОММЕРЧЕСКИМ ПАРТНЕРСТВОМ ПО ПОДДЕРЖКЕ ESTABLISHED BY NON-COMMERCIAL PARTNERSHIP FOR PROMOTION OF ТЕАТРАЛЬНОЙ ДЕЯТЕЛЬНОСТИ И ИСКУССТВА «РОССИЙСКИЙ THEATRE ACTIVITITY AND ARTS «RUSSIAN NATIONAL CENTRE OF THE НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ ЦЕНТР МЕЖДУНАРОДНОГО ИНСТИТУТА ТЕАТРА». INTERNATIONAL THEATRE INSTITUTE» ЗАРЕГИСТРИРОВАН ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЙ СЛУЖБОЙ ПО НАДЗОРУ В СФЕРЕ REGISTERED BY THE FEDERAL AGENCY FOR MASS-MEDIA AND СВЯЗИ И МАССОВЫХ КОММУНИКАЦИЙ. COMMUNICATIONS. СВИДЕТЕЛЬСТВО О РЕГИСТРАЦИИ REGISTRATION LICENSE SMI PI № FS77-34893 СМИ ПИ № ФС77–34893 ОТ 29 ДЕКАБРЯ 2008 ГОДА OF DECEMBER 29TH, 2008 АДРЕС РЕДАКЦИИ: 129594, МОСКВА, EDITORIAL BOARD ADDRESS: УЛ. ШЕРЕМЕТЬЕВСКАЯ, Д. 6, К. 1 129594, MOSCOW, SHEREMETYEVSKAYA STR., 6, BLD. 1 MAIL RUSITI BK RU ЭЛЕКТРОННАЯ ПОЧТА: [email protected] E- : @ . OVER HEATRE DU OLEIL НА ОБЛОЖКЕ : СПЕКТАКЛЬ «1789». THEATRE DU SOLEIL. C : “1789”. T S . DIRECTOR ARIANE MNOUCHKINE, IN 1976 РЕЖИССЁР АРИАНА МНУШКИНА, 1976 Г. WWW.OTLB.WORDPRESS.COM WWW.OTLB.WORDPRESS.COM PHOTOS ARE PROVIDED BY PRESS SERVICES OF GOLDEN MASK, ФОТОГРАФИИ ПРЕДОСТАВЛЕНЫ ПРЕСС-СЛУЖБАМИ ФЕСТИВАЛЕЙ ARLEKIN AND DREAM OF FLIGHT FESTIVALS, TOVSTONOGOV «ЗОЛОТАЯ МАСКА», «АРЛЕКИН», «МЕЧТА О ПОЛЁТЕ», БДТ ИМ. BOLSHOI DRAMA THEATER, GOGOL-CENTRE, MALY THEATRE, ТОВСТОНОГОВА, «ГОГОЛЬ-ЦЕНТРА», МАЛОГО ТЕАТРА, ТЕАТРА ИМ. VAHTANGOV THEATRE, GITIS – RUTI, ET CETERA THEATRE, ВАХТАНГОВА, РУТИ-ГИТИСА, ТЕАТРА ET CETERA, ТЕАТРАЛЬНЫМ PR DEPARTMENT OF A.A.BAKHRUSHIN