From Social to Anthropological Discourse in Gorky: Hypotheses and Rebuttals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dramas of the Bible

^ THE DRAMAS OF THE BIBLE i I BY A. P. DRUCKER 'T^HE STATEMENT that there are dramas in the Bible will ^ probably surprise many of my readers. This surprise is due to various reasons. First of these is the widely prevailing idea that the drama originated in Greece, and that no other nation of antiquity cultivated it ; hence, of course, the Hebrews could boast of no such art. We hear on the other hand, the assertion repeatedly made that the Semites especially had no dramatic genius. i Now, the drama was by no means confined to the Greeks. We find it among the Hindus, where Vishnu is the hero of many old plays. ^ We find it also among the Chinese, where the Dragon-god is made the chief character of a drama in which he is represented as driving out the evil spirits from the dwellings of the godly.-" And the Japanese, too, have a drama, telling of the valiant achievements of their Sun- god.-i We thus see that the drama was not confined to the Greek ; on the other hand, not only do we encounter it among the semi-civilized peoples, but also among barbarians and savages, who, as soon as they attain to a religious consciousness, have their ceremonies in- corporated into dramatic performances.-^ The Indian war-dances, the snake- and other animal-dances, are known to all ; but these are really nothing more than dramatic presentations of religious cere- monies. The Australians had a drama long before the whites discoyered them.' They perform an historical drama to appease the gods for a murder committed in the neiehborhood when the killer is unknown. -

Interactive Multimedia Solutions Developed for the Opening of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre

Interactive Multimedia Solutions Developed for the Opening of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre Nikolay Borisov, Artem Smolin, Denis Stolyarov, Pavel Shcherbakov St. Petersburg National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics, Saint Petersburg State University Abstract. This paper focuses on teamwork by the National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics (NRU ITMO) and the Aleksandrinsky Theatre in preparation of opening of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre. The Russian State Pushkin Academy Drama Theatre, also known as the Alexandrinsky Theatre, is the oldest national theatre in Rus- sia. Many famous Russian actors performed on the Alexandrinsky’s stage and many great directors. May 2013 marked the opening of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre. The theatre complex comprises three buildings: the new stages building, a media center, and the building housing a center of theatre ed- ucation. Several plays shown simultaneously on multiple stages within the new complex’s buildings constituted the opening gala of the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre. The works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky were the plays’ uni- fying theme. NRU ITMO employees developed several interactive theatre pro- ject solutions implemented for the opening of the Alexandrinsky Theatre’s New Stage. Keywords: Theatre, Multimedia, Information Technologies, NRU ITMO, SPbGU 1 Introduction The Russian State Pushkin Academy Drama Theatre, also known as the Alexandrinsky Theatre, is the oldest national theatre in Russia. It was founded in 1756 by the Senate’s decree. The history of the Alexandrinsky Theatre is closely linked to some of the most prominent exponents of Russian culture. -

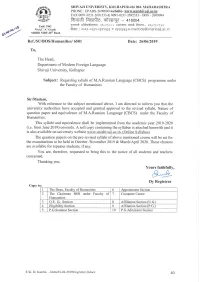

M.A. Russian 2019

************ B+ Accredited By NAAC Syllabus For Master of Arts (Part I and II) (Subject to the modifications to be made from time to time) Syllabus to be implemented from June 2019 onwards. 2 Shivaji University, Kolhapur Revised Syllabus For Master of Arts 1. TITLE : M.A. in Russian Language under the Faculty of Arts 2. YEAR OF IMPLEMENTATION: New Syllabus will be implemented from the academic year 2019-20 i.e. June 2019 onwards. 3. PREAMBLE:- 4. GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE COURSE: 1) To arrive at a high level competence in written and oral language skills. 2) To instill in the learner a critical appreciation of literary works. 3) To give the learners a wide spectrum of both theoretical and applied knowledge to equip them for professional exigencies. 4) To foster an intercultural dialogue by making the learner aware of both the source and the target culture. 5) To develop scientific thinking in the learners and prepare them for research. 6) To encourage an interdisciplinary approach for cross-pollination of ideas. 5. DURATION • The course shall be a full time course. • The duration of course shall be of Two years i.e. Four Semesters. 6. PATTERN:- Pattern of Examination will be Semester (Credit System). 7. FEE STRUCTURE:- (as applicable to regular course) i) Entrance Examination Fee (If applicable)- Rs -------------- (Not refundable) ii) Course Fee- Particulars Rupees Tuition Fee Rs. Laboratory Fee Rs. Semester fee- Per Total Rs. student Other fee will be applicable as per University rules/norms. 8. IMPLEMENTATION OF FEE STRUCTURE:- For Part I - From academic year 2019 onwards. -

Vol. 73, No. 7JULY/AUGUST 1968 Published•By Conway Hall

Vol. 73, No. 7JULY/AUGUST 1968 CONTENTS Eurnmum..• 3 "ULYSSES": THE BOOK OF THE FILM . 5 by Ronald Mason THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF RELIGION . 8 by Dr. H. W. Turner JEREMY BENTFIAM .... 10 by Maurice Cranston, MA MAXIM GORKY•••• • 11 by Richard Clements, aRE. BOOK REVIEW: Gown. FORMutEncs. 15 by Leslie Johnson WHO SAID THAT? 15 Rum THE SECRETARY 16 TO THE EDITOR . 17 PEOPLEOUT OF 11113NEWS 19 DO SOMETHINGNICE FOR SOMEONE 19 SOUTH PLACENaws. 20 Published•by Conway Hall Humanist Centre Red Um Square, London, Wel SOUTH PLACE ETHICAL SOCIETY Omens: Secretary: Mr. H. G. Knight Hall Manager and Lettings Secretary: Miss E. Palmer Hon. Registrar: Miss E. Palmer Hon. Treasurer: Mr. W. Bynner Editor, "The Ethical Record": Miss Barbara Smoker Address: Conway Hall Humanist Centre, Red Lion Square, London, W.C.I (Tel.: CHAncery 8032) SUNDAY MORNING MEETINGS, II a.rn. (Admission free) July 7—Lord SORENSEN Ivory Towers Soprano solos: Laura Carr. July 14—J. STEWART COOK. BSc. Politics and Reality Cello and piano: Lilly Phillips and Fiona Cameron July 21—Dr. JOHN LEWIS The Students' Revolt Piano: Joyce Langley SUNDAY MORNING MEETINGS are then suspended until October 6 S.P.E.S. ANNUAL REUNION Sunday, September 29, 1968, 3 p.m. in the Large Hall at CONWAY HUMANIST CENTRE Programme of Music (3 p.m.) Speeches by leaders of Humanist organisations (3.30 P.m.) Guest of Honour: LORD WILLIS Buffet Tea (5 p.m.) Tickets free from General Secretary CONWAY DISCUSSIONS will resume on Tuesdays at 6.45 p.m. from October 1 The 78th season of SOUTH PLACE SUNDAY CONCERTS will open on October 6 at 6.30 p.m. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR RICHARD M. MILES Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 2, 2007 Copyright 2015 ADST FOREIGN SERVICE POSTS Oslo, Norway. Vice-Consul 1967-1969 Washington. Serbo-Croatian language training. 1969-1970 Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Consul 1970-1971 Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Second Secretary, Political Section 1971-1973 Washington. Soviet Desk 1973-1975 Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany. US Army Russian Institute 1975-1976 Advanced Russian language training Moscow. Second Secretary. Political Section 1976-1979 Washington. Yugoslav Desk Officer 1979-1981 Washington. Politico-Military Bureau. Deputy Director, PM/RSA 1981-1982 Washington. Politico-Military Bureau. Acting Director, PM/RSA 1982-1983 Washington. American Political Science Association Fellowship 1983-1984 Worked for Senator Hollings. D-SC Belgrade. Political Counselor 1984-1987 Harvard University. Fellow at Center for International Affairs 1987-1988 Leningrad. USSR. Consul General 1988-1991 Berlin, Germany. Leader of the Embassy Office 1991-1992 Baku. Azerbaijan. Ambassador 1992-1993 1 Moscow. Deputy Chief of Mission 1993-1996 Belgrade. Chief of Mission 1996-1999 Sofia, Bulgaria. Ambassador 1999-2002 Tbilisi, Georgia. Ambassador 2002-2005 Retired 2005 INTERVIEW Q: Today is February 21, 2007. This is an interview with Richard Miles, M-I-L-E-S. Do you have a middle initial? MILES: It’s “M” for Monroe, but I seldom use it. And I usually go by Dick. Q: You go by Dick. Okay. And this is being done on behalf of the Association of Diplomatic Studies and Training and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. Well Dick, let’s start at the beginning. -

Socialist Realism Seen in Maxim Gorky's Play The

SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 i ii iii HHaappppiinneessss aallwwaayyss llooookkss ssmmaallll wwhhiillee yyoouu hhoolldd iitt iinn yyoouurr hhaannddss,, bbuutt lleett iitt ggoo,, aanndd yyoouu lleeaarrnn aatt oonnccee hhooww bbiigg aanndd pprreecciioouuss iitt iiss.. (Maxiim Gorky) iv Thiis Undergraduatte Thesiis iis dediicatted tto:: My Dear Mom and Dad,, My Belloved Brotther and Siistters.. v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to praise Allah SWT for the blessings during the long process of this undergraduate thesis writing. I would also like to thank my patient and supportive father and mother for upholding me, giving me adequate facilities all through my study, and encouragement during the writing of this undergraduate thesis, my brother and sisters, who are always there to listen to all of my problems. I am very grateful to my advisor Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, S.S., M.Hum. for helping me doing my undergraduate thesis with his advice, guidance, and patience during the writing of my undergraduate thesis. My gratitude also goes to my co-advisor Dewi Widyastuti, S.Pd., M.Hum. -

Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat"

Swarthmore College Works Russian Faculty Works Russian 2008 "Mother", As Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia's "Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat" Sibelan E.S. Forrester Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Sibelan E.S. Forrester. (2008). ""Mother", As Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia's "Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat"". American Contributions to the 14th International Congress of Slavists: Ohrid 2008. Volume 2, 51-67. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian/249 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mother as Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia’s Sof´ia Petrovna Rewrites Maksim Gor´kii’s Mat´* Sibelan E. S. Forrester Lidiia Chukovskaia’s novella Sof´ia Petrovna (henceforth abbreviated as SP) has gained a respectable place in the canon of primary sources used in the United States to teach about the Soviet period,1 though it may appear on history syllabi more often than in (occasional) courses on Russian women writers or (more common) surveys of Russian or Soviet literature. The tendency to read and use the work as a historical document begins with the author herself: Chukovskaia consistently emphasizes its value as a testimonial and its uniqueness as a snapshot of the years when it was writ- ten. -

Conscious Responsibility 2 Contents

Social Report 2016 World Without Barriers. VTB Group Conscious Responsibility 2 Contents VTB Group in 2016 4 3.3. Internal communications and corporate culture 50 Abbreviations 6 3.4. Occupational health and safety 53 Statement of the President and Chairman of the Management Board of VTB Bank (PJSC) 8 4. Social environment 56 1. About VTB Group 10 4.1. Development of the business environment 57 1.1. Group development strategy 12 4.2. Support for sports 63 1.2. CSR management 13 4.3. Support for culture and the arts 65 1.3. Internal (compliance) control 16 4.4. Support for health care and education 69 1.4. Stakeholder engagement 17 4.5. Support for vulnerable social groups 71 2. Market environment 26 5. Natural environment 74 2.1. Support for the public sector and socially significant business 27 5.1. Sustainable business practices 74 2.2. Support for SMBs 34 5.2. Financial support for environmental projects 77 2.3. Quality and access to banking services 35 6. About the Report 80 2.4. Socially significant retail services 38 7. Appendices 84 3. Internal environment 44 7.1. Membership in business associations 84 3.1. Employee training and development 46 7.2 GRI content index 86 3.2. Employee motivation and remuneration 49 7.3. Independent Assurance Report 90 VTB Social Report 2016 About VTB Group Market environment Internal environment Social environment Natural environment About the Report Appendices VTB Group in 2016 4 VTB Group in 2016 5 RUB 51.6 billion earned 72.7 thousand people 274.9 thousand MWh in net profit employed by the Group -

Halperin David M Traub Valeri

GAY SHAME DAVID M. HALPERIN & VALERIE TRAUB I he University of Chicago Press C H I C A G 0 A N D L 0 N D 0 N david m. h alperin is theW. H. Auden Collegiate Professor of the History and Theory of Sexuality at the University of Michigan. He is the author of several books, including Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography (Oxford University Press, 1995) and, most re cently, What Do Gay Men Want? An Essay on Sex, Risk, and Subjectivity (University of Michi gan Press, 2007). valerie traub is professor ofEnglish andwomen's studies at the Uni versity of Michigan, where she chairs the Women's Studies Department. She is the author of Desire and Anxiety: Circulations of Sexuality in Shakesptanan Drama (Routledge, 1992) and The Renaissance of Ltsbianism in Early Modem England (Cambridge University Press, 2002). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago Al rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America 17 16 15 14 13 12 ii 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31437-2 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31438-9 (paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-31437-5 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-31438-3 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gay shame / [edited by] David M. Halperin and Valerie Traub. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31437-2 (cloth: alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-31437-5 (cloth: alk. -

Yuri Lyubimov: Thirty Years at the Taganka Theatre

YURY LYUBIMOV Contemporary Theatre Studies A series of books edited by Franc Chamberlain, Nene College, Northampton, UK Volume 1 Playing the Market: Ten Years of the Market Theatre, Johannesburg, 1976–1986 Anne Fuchs Volume 2 Theandric: Julian Beck’s Last Notebooks Edited by Erica Bilder, with notes by Judith Malina Volume 3 Luigi Pirandello in the Theatre: A Documentary Record Edited by Susan Bassnett and Jennifer Lorch Volume 4 Who Calls the Shots on the New York Stages? Kalina Stefanova-Peteva Volume 5 Edward Bond Letters: Volume I Selected and edited by Ian Stuart Volume 6 Adolphe Appia: Artist and Visionary of the Modern Theatre Richard C.Beacham Volume 7 James Joyce and the Israelites and Dialogues in Exile Seamus Finnegan Volume 8 It’s All Blarney. Four Plays: Wild Grass, Mary Maginn, It’s All Blarney, Comrade Brennan Seamus Finnegan Volume 9 Prince Tandi of Cumba or The New Menoza, by J.M.R.Lenz Translated and edited by David Hill and Michael Butler, and a stage adaptation by Theresa Heskins Volume 10 The Plays of Ernst Toller: A Revaluation Cecil Davies Please see the back of this book for other titles in the Contemporary Theatre Studies series YURY LYUBIMOV AT THE TAGANKA THEATRE 1964–1994 Birgit Beumers University of Bristol, UK harwood academic publishers Australia • Canada • China • France • Germany • India Japan • Luxembourg • Malaysia • The Netherlands • Russia Singapore • Switzerland • Thailand • United Kingdom Copyright © 1997 OPA (Overseas Publishers Association) Amsterdam B.V. Published in The Netherlands by Harwood Academic Publishers. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Bolton High Gets

MemorisI Dsy ’89 will sperk memories of brave men, women By Nancy Concelman It s a time for reflection on what our country Kowalski was aboard the U.S. Navy ship that ,52-piece group. Manchester Herald .stands for,” Osella said. brought MacArthur back to the Philippines in He and his crewmates helped lead the first While Osella is quietly remembering veterans Those who turn out Monday for Manchester’s 194.5, three years after the Japanese victory over American bombing raid over Tokyo in April 1942 who have .survived, those who have died and those Memorial Day parade will see Parade Marshal American and Filipino forces. by bringing planes within 400 feet of the Tokyo who cannot be found to this day. World War II will Ronald Osella looking snappy in his dress U.S. The USS Nashville was MacArthur’s flagship coast. be remembered in a quiet cemetery off Cider Mill three times during the war. Kowalski said. It was Army Reserve uniform, proudly leading “ We pulled the operation off,” Kowalski said. Road in Andover as veteran William Kowalski marchers and waving at friends. Kowalski's home for part of his eight-year Navy "W e sank two Japane.se ships.” tells his story. career. But Osella. a major in the reserves, will be Kowalski will be one of many speakers, young A Kowalski, 72. was among those who helped Gen A ship’s tailor. Kowalski "sewed and pressed thinking about something other than the bands and old. who will remind citizens in area towns Douglas MacArthur keep his famous promi.se, " I for 1,200 men" and helped start the IR-piece USS CARS and the crowds.