Status & Source of Potential Delays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Update Conflict Displacement Faryab Province 22 May 2013

Update conflict displacement Faryab Province 22 May 2013 Background On 22 April, Anti-Government Elements (AGE) launched a major attack in Qaysar district, making Faryab province one of their key targets of the spring offensive. The fighting later spread to Almar district of Faryab province and Ghormach of Badghis Province, displacing approximately 2,500 people. The attack in Qaysar was well organized, involving several hundred AGE fighters. According to Shah Farokh Shah, commander of 300 Afghan local policemen in Khoja Kinti, some of the insurgents were identified as ‘Chechens and Pakistani Taliban’1. The Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) has regained control of the Qaysar police checkpoints. The plan is to place 60 Afghan local policemen (ALPs) at the various checkpoints in the Khoja Kinti area. Quick Response Forces with 40 ALPs have already been posted. ANSF is regaining control in Ghormach district. Similar efforts are made in Almar and Pashtun Kot. Faryab OCCT has decided to replace ALP and ANP, originally coming from Almar district, with staff from other districts. Reportedly the original ALP and ANP forces have sided with the AGE. Security along the Shiberghan - Andkhoy road has improved. The new problem area is the Andkhoy - Maymana road part. 200 highway policemen are being recruited to secure the Maymana - Shibergan highway. According to local media reports the Taliban forces have not been defeated and they are still present in the area. There may be further displacement in view of the coming ANSF operations. Since the start of this operation on 22 April, UNAMA documented 18 civilian casualties in Qaysar district from ground engagements between AGEs and ANSF, IED incidents targeting ANP and targeted killings. -

Health and Integrated Protection Needs in Kunduz Province

[Compa ny name] Assessment Report- Health and Integrated Protection Needs in Kunduz Province Dr. Noor Ahmad “Ahmad” Dr. Mirza Jan Hafiz Akbar Ahmadi Vijay Raghavan Final Report Acknowledgements The study team thank representatives of the following institutions who have met us in both Kabul and Kunduz during the assessment. WHO – Kabul and Kunduz; UNOCHA – Kunduz; MSF (Kunduz); UNHCR- Kunduz; Handicap International Kunduz; Provincial Health Directorate, Kunduz; Regional Hospital, Kunduz; Afghanistan Red Crescent Society (ARCS), Kunduz; DoRR, Kunduz; Swedish Committee for Afghanistan, Kunduz; JACK BPHS team in Kunduz Thanks of INSO for conducting the assessment of the field locations and also for field movements Special thanks to the communities and their representatives – Thanks to CHNE and CME staff and students District Hospital staff of Imam Sahib Our sincere thanks to the District wise focal points, health facility staff and all support staff of JACK, Kunduz who tirelessly supported in the field assessment and arrangement of necessary logistics for the assessment team. Thanks to Health and Protection Clusters for their constant inputs and support. Thanks to OCHA-HFU team for their feedback on our previous programme and that helped in refining our assessment focus and added the components of additional issues like operations, logistics and quality of supplies which were discussed elaborately with the field team of JACK. Thanks to Access and Security team in OCHA for their feedback on access and security sections. Page 2 of 102 Final -

Gouvernance Des Coopératives Agricoles Dans Une Économie En Reconstruction Après Conflit Armé : Le Cas De L’Afghanistan Mohammad Edris Raouf

Gouvernance des coopératives agricoles dans une économie en reconstruction après conflit armé : le cas de l’Afghanistan Mohammad Edris Raouf To cite this version: Mohammad Edris Raouf. Gouvernance des coopératives agricoles dans une économie en reconstruc- tion après conflit armé : le cas de l’Afghanistan. Gestion et management. Université Paul Valéry- Montpellier III, 2018. Français. NNT : 2018MON30092. tel-03038739 HAL Id: tel-03038739 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03038739 Submitted on 3 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ PAUL VALÉRY DE MONTPELLIER III ÉCOLE DOCTORALE ÉCONOMIE ET GESTION DE MONTPELLIER ED 231, LABORATOIRE ART- DEV (ACTEURS, RESSOURCES ET TERRITOIRES DANS LE DÉVELOPPEMENT), SUP-AGRO MONTPELLIER Gouvernanceou e a cedescoopéat des coopératives esag agricoles coesda dans su une eéco économie o ee en reconstruction après conflit armé, le cas de l’Afghanistan By: Mohammad Edris Raouf Under Direction of Mr. Cyrille Ferraton MCF -HDR en sciences économiques, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, -

Download Map (PDF | 2.37

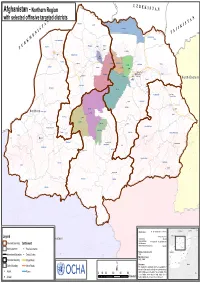

in te rn a tio n U a Z Khamyab l B Afghanistan - Northern Region E KIS T A N Qarqin with selected offinsive targeted districts A N Shortepa T N Kham Ab l a Qarqin n S o A i I t a n K T Shortepa r e t n S i JI I Kaldar N T A E Sharak Hairatan M Kaldar K Khani Chahar Bagh R Mardyan U Qurghan Mangajek Mangajik T Mardyan Dawlatabad Khwaja Du Koh Aqcha Aqcha Andkhoy Chahar Bolak Khwaja Du Koh Fayzabad Khulm Balkh Nahri Shahi Qaramqol Khaniqa Char Bolak Balkh Mazari Sharif Fayzabad Mazari Sharif Khulm Shibirghan Chimtal Dihdadi Nahri Shahi NorthNorth EasternEastern Dihdadi Marmul Shibirghan Marmul Dawlatabad Chimtal Char Kint Feroz Nakhchir Hazrati Sultan Hazrati Sultan Sholgara Chahar Kint Sholgara Sari Pul Aybak NorthernShirin Tagab Northern Sari Pul Aybak Qush Tepa Sayyad Sayyad Sozma Qala Kishindih Dara-I-Sufi Payin Khwaja Sabz Posh Sozma Qala Darzab Darzab Kishindih Khuram Wa Sarbagh Almar Dara-i-Suf Maymana Bilchiragh Sangcharak (Tukzar) Khuram Wa Sarbagh Sangcharak Zari Pashtun Kot Gosfandi Kohistanat (Pasni) Dara-I-Sufi Bala Gurziwan Ruyi Du Ab Qaysar Ruyi Du Ab Balkhab(Tarkhoj) Kohistanat Balkhab Kohistan Kyrgyzstan China Uzbekistan Tajikistan Map Doc Name: A1_lnd_eastern_admin_28112010 Legend CapitalCapital28 November 2010 Turkmenistan Jawzjan Badakhshan Creation Date: Kunduz Western WGS84 Takhar Western Balkh Projection/Datum: http://ochaonline.un.org/afghanistan Faryab Samangan Baghlan Provincial Boundary Settlement Web Resources: Sari Pul Nuristan Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:640,908 Badghis Bamyan Parwan Kunar Kabul !! Maydan -

PROFILE 2020 “The Source of Premium Quality Petroleum Products” CONTENTS

COMPANY PROFILE 2020 “The Source of Premium Quality Petroleum Products” CONTENTS ABOUT US 01 OUR STORY 02 SERVICES 03 OUR ASSETS 04 PRODUCTS 05 Afghan Petrol Group Ltd – The Premium Fuel & Gas Source 01 ABOUT US Afghan Petrol Group Ltd. is a joint import and export company, specializing mostly in fuel, gas, storage, transportation and retailing, founded in 2004 as result of fuel shortage had hit the country and total lack of fuel storages in conjunction with expansion of family enterprise companies. Today the company is one of the leading fuel retail operators in the country and the third largest fuel importer and distributor with sufficient storage capacity of 83 million liters and expertise with a skilled motivated workforce to expand oil products in Afghanistan, Afghan Petrol Group currently holds over 15 % share of fuel market imports. The company provides premium fuel and gas for in several locations of Afghanistan specially in border points of Hairatan, Aqina, and Tourghundi, which are the main three location that the petroleum products are sourced and imported from neighbor countries. The company has built the most modern and standardized strategic fuel and gas storage at three border locations to operate properly and can provide different kind of fuel within it’s specification. MISSION VISION The market in the country is running There is increasingly health concerns over the poor quality of fuel and here with using the hazardous and our company’s task is to provide contaminated fuel products in the superior quality of petroleum products country and as a premium energy to every part of the country for facilitator we aim to make sure every consumers who are aware of the quality one will use such high quality of product of fuel to use. -

Misuse of Licit Trade for Opiate Trafficking in Western and Central

MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA A Threat Assessment A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2012 MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Afghan Opiate Trade Project of the Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA), within the framework of UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and in Pakistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions that shared their knowledge and data with the report team including, in particular, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan, the Ministry of Counter Narcotics of Afghanistan, the customs offices of Afghanistan and Pakistan, the World Customs Office, the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre, the Customs Service of Tajikistan, the Drug Control Agency of Tajikistan and the State Service on Drug Control of Kyrgyzstan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Programme management officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Natascha Eichinger (Consultant) Platon Nozadze (Consultant) Hayder Mili (Research expert, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Yekaterina Spassova (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Hamid Azizi (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Shaukat Ullah Khan (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) A. -

Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Afghanistan’S Faryab Province Geert Gompelman ©2010 Feinstein International Center

JANUARY 2011 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship between Aid and Security in Afghanistan’s Faryab Province Geert Gompelman ©2010 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Author Geert Gompelman (MSc.) is a graduate in Development Studies from the Centre for International Development Issues Nijmegen (CIDIN) at Radboud University Nijmegen (Netherlands). He has worked as a development practitioner and research consultant in Afghanistan since 2007. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank his research colleagues Ahmad Hakeem (“Shajay”) and Kanishka Haya for their assistance and insights as well as companionship in the field. Gratitude is also due to Antonio Giustozzi, Arne Strand, Petter Bauck, and Hans Dieset for their substantive comments and suggestions on a draft version. The author is indebted to Mervyn Patterson for his significant contribution to the historical and background sections. Thanks go to Joyce Maxwell for her editorial guidance and for helping to clarify unclear passages and to Bridget Snow for her efficient and patient work on the production of the final document. -

Afghanistan National Railway Plan and Way Forward

Afghanistan National Railway Plan and Way Forward MOHAMMAD YAMMA SHAMS Director General & Chief Executive Officer Afghanistan Railway Authority Nov 2015 WHY RAILWAY IN AFGHANISTAN ? → The Potential → The Benefits • Affinity for Rail Transportation Pioneer Development of Modern – Primary solution for landlocked, Afghanistan developing countries/regions – At the heart of the CAREC and Become Part of the International ECO Program Rail Community – 75km of railroad vs 40,000 km of – Become long-term strategic partner road network to various countries – Rich in minerals and natural – Build international rail know-how resources – rail a more suitable (transfer of expertise) long term transportation solutions Raise Afghanistan's Profile as a than trucking. Transit Route • Country Shifting from Warzone – Penetrate neighbouring countries to Developing State Rail Market including China, Iran, Turkey and countries in Eastern – Improved connection to the Europe. community and the region (access – Standard Gauge has been assessed to neighbouring countries) as the preferred system gauge. – Building modern infrastructure – Dual gauge (Standard and Russian) in – Facilitate economic stability of North to connect with CIS countries modern Afghanistan STRATEGIC LOCATION OF AFGHANISTAN Kazakhstan China MISSING LINKS- and ASIAN RAILWAY TRANS-ASIAN RAILWAY NETWORK Buslovskaya St. Petersburg RUSSIAN FEDERATION Yekaterinburg Moscow Kotelnich Omsk Tayshet Petropavlovsk Novosibirsk R. F. Krasnoe Syzemka Tobol Ozinki Chita Irkutsk Lokot Astana Ulan-Ude Uralsk -

Phosphate Occurrence and Potential in the Region of Afghanistan, Including Parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan

Phosphate Occurrence and Potential in the Region of Afghanistan, Including Parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan By G.J. Orris, Pamela Dunlap, and John C. Wallis With a section on geophysics by Jeff Wynn Open-File Report 2015–1121 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2015 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Orris, G.J., Dunlap, Pamela, and Wallis, J.C., 2015, Phosphate occurrence and potential in the region of Afghanistan, including parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, with a section on geophysics by Jeff Wynn: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2015-1121, 70 p., http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/ofr20151121. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Contents -

Highlights Situation Overview

Afghanistan: Northeast Situation Situation Report No. 3 (as of 03 October 2015) This report is produced by OCHA Afghanistan in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 02 to 03 October 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 04 October 2015. Highlights The MSF hospital in Kunduz City is severely damaged following an air strike on 3 October with operations significantly affected. Civilian deaths, including nine humanitarian workers, and at least 37 civilians injured, also resulted Multiple armed entities, including ANDSF, non-state armed groups and local armed actors are operating in Kunduz City Road and air access to Kunduz City remain highly restricted, with electricity and water cut off in large areas and food increasingly hard to come by For those displaced to other areas of the Northeast, needs remain to be established, with assessments underway in some areas of displacement including Source: OCHA Takhar and Badakhshan provinces The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. When greater access is gained for assessments and response, sufficient capacity is available in-country to respond to the immediate needs Situation Overview At 0215 on 3 October, an air strike occurred affecting the Médecins sans Frontières hospital in Kunduz City, resulting in the deaths of patients, medical staff, and other civilians. MSF has reported that nine of its staff were killed in the incident, and that 37 people were seriously wounded during the bombing, of whom 19 are MSF staff. As a consequence, fire has destroyed the hospital, with some patients moved to other MSF facilities and the regional hospital. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Stabilization and Connectivity Uzbekistan's Dual-Track Strategy Towards Afghanistan

POLICY BRIEF Stabilization and Connectivity Uzbekistan’s dual-track strategy towards Afghanistan Timor Sharan, Andrew Watkins This policy brief explores Uzbekistan’s engagement with Afghanistan in 2021 and beyond, in light of the ongoing U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan. The brief discusses how increasing uncertainty surrounding the nature and timing of the U.S. withdrawal could affect Uzbekistan’s regional and domestic security. It examines Uzbekistan’s future engagement with Afghanistan, highlighting key convergence areas around which Europe and Central Asia could cooperate in Afghanistan and find opportunities for broader engagement beyond the current peace process. Before the nineteenth century’s Russian colonisation of Central has led to a more dynamic relationship with Kabul, rooted in Asia and the ‘Great Game,’ Afghanistan and Central Asia had infrastructure and connectivity schemes and projects. Tashkent long been seen by outsiders and residents as a single cultural, is playing a constructive role in the Afghan peace process, civilisational and political space. Geopolitical tensions between working alongside a handful of leading global and regional the Russian and British Empires interrupted these historical ties players attempting to stabilise Afghanistan. for a century until the rise of Afghanistan’s communist regime in the 1970s and the Soviet invasion of the 1980s. The collapse Uzbekistan has begun reaching out to both sides of the conflict, of the Soviet Union in 1989, the subsequent independence of maintaining warm relations with Kabul and gradually developing Central Asian countries, and the civil war in Afghanistan divided closer ties with the Taliban. At times this has been somewhat the region once again: Afghanistan became perceived as a of a tightrope act and not without complication.