ARCHIVE – Volume 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hana Mae Lee Has Perfect Pitch H&M + Margiela Target + Neiman

NOVEMBER 2012 FREE Hana Mae Lee Has Perfect Pitch H&M + Margiela Target + Neiman Marcus MGM Grand Gambles on Vietnam Happiness From Bai Ling yellowmags.com from t h E E d i t or i N c h i ef Each year, I have the pleasure of making a trip to Beverly Hills to attend the annual Operation Smile gala in support of a charity in which I have strong conviction. Whereas, I usually visit for three or four days, this time was for only two. As is often the case, the less time one has, the more there is to do. I am not complaining, mind you, because it resulted in two wonderful interviews that are included in this issue. We first interviewed Bai Ling several years ago when she was filming Love Ranch with Helen Mirren and Joe Pesci. This year, we were fortunate to have her join us at the Operation Smile gala where she attracted considerable interest on the red carpet as she struck her signature “Bai Ling” poses. The following day, we met for an interview during which Bai offered us some insight into what drives her and counters some of her public persona. If you happen to look at her acting resume on imdb, you cannot help but be impressed by the sheer volume of this actor’s work. Millions of fans have enjoyed the film Pitch Perfect which was released last month. I had not had the opportunity to see it when I received a call from Hana Mae Lee’s publicist asking if I would like to interview her. -

Encyclopedia of Drugs, Alcohol, and Addictive Behavior 2Nd Ed Vol

EDA&AB-ttlpgs/v1 10/27.qx4 10/27/00 3:49 PM Page 1 ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR ENCYCLOPEDIA of DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR Editorial Board EDITOR IN CHIEF Rosalyn Carson-DeWitt, M.D. Durham, North Carolina EDITORS Kathleen M. Carroll, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Psychiatry Yale University School of Medicine Jeffrey Fagan, Ph.D. Professor of Public Health Joseph L. Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University Henry R. Kranzler, M.D. Professor of Psychiatry University of Connecticut School of Medicine Michael J. Kuhar, Ph.D. Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar and Candler Professor Yerkes Regional Primate Center EDA&AB-ttlpgs/v1 10/27.qx4 10/27/00 3:49 PM Page 3 ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR ENCYCLOPEDIA of DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR SECOND EDITION VOLUME 1 A – D ROSALYN CARSON-DEWITT, M.D. Editor in Chief Durham, North Carolina Copyright © 2001 by Macmillan Reference USA, an imprint of the Gale Group All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Macmillan Reference USA Macmillan Reference USA An imprint of the Gale Group An imprint of the Gale Group 1633 Broadway 27500 Drake Rd. New York, NY 10019 Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 Printed in the United States of America printing number 12345678910 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of drugs, alcohol, and addictive behavior / Rosalyn Carson-DeWitt, editor-in-chief.–Rev. ed. p. cm. Rev. ed. -

Product Guide

AFM PRODUCTPRODUCTwww.thebusinessoffilmdaily.comGUIDEGUIDE AFM AT YOUR FINGERTIPS – THE PDA CULTURE IS HAPPENING! THE FUTURE US NOW SOURCE - SELECT - DOWNLOAD©ONLY WHAT YOU NEED! WHEN YOU NEED IT! GET IT! SEND IT! FILE IT!© DO YOUR PART TO COMBAT GLOBAL WARMING In 1983 The Business of Film innovated the concept of The PRODUCT GUIDE. • In 1990 we innovated and introduced 10 days before the major2010 markets the Pre-Market PRODUCT GUIDE that synced to the first generation of PDA’s - Information On The Go. • 2010: The Internet has rapidly changed the way the film business is conducted worldwide. BUYERS are buying for multiple platforms and need an ever wider selection of Product. R-W-C-B to be launched at AFM 2010 is created and designed specifically for BUYERS & ACQUISITION Executives to Source that needed Product. • The AFM 2010 PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is published below by regions Europe – North America - Rest Of The World, (alphabetically by company). • The Unabridged Comprehensive PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH contains over 3000 titles from 190 countries available to download to your PDA/iPhone/iPad@ http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/Europe.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/NorthAmerica.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/RestWorld.doc The Business of Film Daily OnLine Editions AFM. To better access filmed entertainment product@AFM. This PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is divided into three territories: Europe- North Amerca and the Rest of the World Territory:EUROPEDiaries”), Ruta Gedmintas, Oliver -

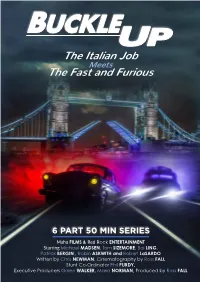

Brochures, Props, Advertising Material and Scripts

BUCKLE UP The Italian Job Meets The Fast and Furious 6 PART 50 MIN SERIES Maha FILMS & Red Rock ENTERTAINMENT Starring Michael MADSEN, Tom SIZEMORE, Bai LING, Patrick BERGIN , Robin ASKWITH and Robert LaSARDO Written by Chris NEWMAN, Cinematography by Ross FALL Stunt Co-Ordinator Phil PURDY, Executive Producers Galen WALKER, Maria NORMAN, Produced by Ross FALL Buckle Up 1 DISCLAIMER: Red Rock Entertainment Ltd is not authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The content of this promotion is not authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA). Reliance on the promotion for the purpose of engaging in any investment activity may expose an individual to a significant risk of losing all of the investment. UK residents wishing to participate in this promotion must fall into the category of sophisticated investor or high net worth individual as outlined by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). BUCKLE UP CONTENTS 4 Concept 5 Synopsis 6 | 7 Series Bible 8 | 15 Cast 16 Director 17 Production 18 | 19 Executive Producers 21 | 22 Perks & Benefits 22 Equity THE CONCEPT The idea came about when brother arranges to buy the Star Like the film The Warriors, Elgar the writer Chris Newman was of Africa on the black market has to make it back from where watching the 1979 film The from an Arab Prince. He sends a he steals the diamond to the Warriors where a New York courier to pick up the diamond younger brother but this time gang had to make it back to necklace. Unknown to him his it’s Cornwall and the destination Coney Island from Manhattan brother has also learned about is London and it’s got to be after a charismatic gang leader the diamond but he doesn’t done in 8 hours. -

Progressive-Era Hygienic Ideology, Waste, and Upton Sinclair's the Jungle

Processes of Elimination: Progressive-Era Hygienic Ideology, Waste, and Upton Sinclair's The Jungle J. Michael Duvall Disappointed that The Jungle did not result in a ground-swell of socialist sentiment, Upton Sinclair famously evaluated his best-known novel as a kind of failure. "I aimed at the public's heart," he wrote, "and by accident hit them in the stomach."1 Yet no one could doubt that Sinclair aimed at the public's heart, given The Jungle's sentimentality, but the idea that he hit the public in the stomach by accident obviously overstates the case. More likely, Sinclair aimed at the public's stomach, but hoped that the blow would cause moral outrage and a lasting change in the public's heart. He was following a venerable recipe for fomenting moral judgment: begin with your basic jeremiad, ladle in liberal amounts of the filthy and the revolting, and stir.2 As William Ian Miller affirms in The Anatomy of Disgust, Sinclair's gambit is right on target. Disgust and moral judgment are nearly always wrapped up together, for "except for the highest-toned discourses of moral philosophers, moral judgment seems almost to demand the idiom of disgust. That makes me sick! What revolting behavior! You give me the creeps!'3 Miller's illustration of how disgust surfaces in expressions of moral judgment highlights that disgust is encoded bodily. This is evidenced in the adjectives "sick" and "revolting" and the noun "the creeps," all three quite visceral in their tone and implications. Invoking the disgusting is but one way in which The Jungle enlists the body, in this case, the bodies of readers themselves. -

Alternative Titles Index

VHD Index - 02 9/29/04 4:43 PM Page 715 Alternative Titles Index While it's true that we couldn't include every Asian cult flick in this slim little vol- ume—heck, there's dozens being dug out of vaults and slapped onto video as you read this—the one you're looking for just might be in here under a title you didn't know about. Most of these films have been released under more than one title, and while we've done our best to use the one that's most likely to be familiar, that doesn't guarantee you aren't trying to find Crippled Avengers and don't know we've got it as The Return of the 5 Deadly Venoms. And so, we've gathered as many alternative titles as we can find, including their original language title(s), and arranged them in alphabetical order in this index to help you out. Remember, English language articles ("a", "an", "the") are ignored in the sort, but foreign articles are NOT ignored. Hey, my Japanese is a little rusty, and some languages just don't have articles. A Fei Zheng Chuan Aau Chin Adventure of Gargan- Ai Shang Wo Ba An Zhan See Days of Being Wild See Running out of tuas See Gimme Gimme See Running out of (1990) Time (1999) See War of the Gargan- (2001) Time (1999) tuas (1966) A Foo Aau Chin 2 Ai Yu Cheng An Zhan 2 See A Fighter’s Blues See Running out of Adventure of Shaolin See A War Named See Running out of (2000) Time 2 (2001) See Five Elements of Desire (2000) Time 2 (2001) Kung Fu (1978) A Gai Waak Ang Kwong Ang Aau Dut Air Battle of the Big See Project A (1983) Kwong Ying Ji Dut See The Longest Nite The Adventures of Cha- Monsters: Gamera vs. -

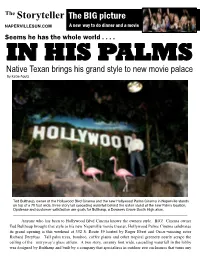

Storyteller the BIG Picture NAPERVILLESUN.COM a New Way to Do Dinner and a Movie Seems He Has the Whole World

The Storyteller The BIG picture NAPERVILLESUN.COM A new way to do dinner and a movie Seems he has the whole world . IN HIS PALMS Native Texan brings his grand style to new movie palace By Katie Foutz Ted Bulthaup, owner of the Hollywood Blvd Cinema and the new Hollywood Palms Cinema in Naperville stands on top of a 70 foot wide, three story tall cascading waterfall behind the usher stand at the new Palms location. Opulence and customer satisfaction are goals for Bulthaup, a Downers Grove South High alum. _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Anyone who has been to Hollywood Blvd Cinema knows the owners style. BIG! Cinema owner Ted Bulthaup brought that style to his new Naperville movie theater, Hollywood Palms Cinema celebrates its grand opening is this weekend at 352 S. Route 59 hosted by Roger Ebert and Oscar-winning actor Richard Dreyfuss. Tall palm trees, bamboo, coffee plants and other tropical greenery nearly scrape the ceiling of the entryway’s glass atrium. A two story, seventy foot wide, cascading waterfall in the lobby was designed by Bulthaup and built by a company that specializes in outdoor zoo enclosures that turns any conversation up to a shouting match over the rush of Hedren, Roger Ebert and more to call or write letters falling water. An art deco pair of gold winged men in support of “The Wizard of Oz” Munchkins re- flanking the screen in one auditorium stand 17 feet ceiving their star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. tall and were movie props in the 20th Century Fox He’s known the famous Little People for years and warehouse. -

Iuscholarworks Dr. Ruth Clifford Engs Presentations, Publications

Indiana University Bloomington IUScholarWorks Dr. Ruth Clifford Engs Presentations, Publications & Research Data Collection Citation for this item To obtain the citation format and information for this document go to: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/17143 The Collection This document is part of a collection that serves two purposes. First, it is a digital archive for a sampling of unpublished documents, presentations, questionnaires and limited publications resulting from over forty years of research. Second, it is a public archive for data on college student drinking patterns on the national and international level collected for over 20 years. Research topics by Dr. Engs have included the exploration of hypotheses concerning the determinants of behaviors such as student drinking patterns; models that have examine the etiology of cycles of prohibition and temperance movements, origins of western European drinking cultures (attitudes and behaviors concerning alcohol) from antiquity, eugenics, Progressive Era, and other social reform movements with moral overtones-Clean Living Movements; biographies of health and social reformers including Upton Sinclair; and oral histories of elderly monks. This collection is found at IUScholarWorks: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/16829 Indiana University Archives Paper manuscripts and material for Dr. Engs can be found in the IUArchives http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/findingaids/view?doc.view=entire_text&docId=InU-Ar- VAC0859 1 Engs- American Cycles of Prohibition. Paper presented: Kettil Bruun Annual meeting. June 2. 1992. AMERICAN CYCLES OF PROHIBITION: DO THEY HAVE ROOTS IN ANCIENT DRINKING NORMS ? Ruth C. Engs, Professor. Applied Health Science, HPER 116, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405. Paper Presented: Kettil Bruun Society's Alcohol Epidemiology Meeting. -

Viewed the Manuscript at One Stage Or Another and Forced Me to Think Through Ideas and Conclusions in Need of Refinement

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 BLACK BASEBALL, BLACK ENTREPRENEURS, BLACK COMMUNITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Michael E. -

ACNP 57Th Annual Meeting: Poster Session I

www.nature.com/npp ABSTRACTS COLLECTION ACNP 57th Annual Meeting: Poster Session I Sponsorship Statement: Publication of this supplement is sponsored by the ACNP. Individual contributor disclosures may be found within the abstracts. Asterisks in the author lists indicate presenter of the abstract at the annual meeting. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0266-7 M1. Lifespan Effects of Early Life Stress on Aging-Related Conclusions: These findings suggest a role for ELA in the form Trajectory of Memory Decline of poor maternal care in increasing the likelihood to development of peripheral IR, altered central glucocorticoid function and Benedetta Bigio*, Danielle Zelli, Timothy Lau, Paolo de Angelis, corresponding anxiety states in adulthood, and that these factors Daniella Miller, Jonathan Lai, Anisha Kalidindi, Susan Harvey, Anjali may encode lifelong susceptibility to pathophysiological aging. Ferris, Aleksander Mathe, Francis Lee, Natalie Rasgon, Bruce McEwen, Given our earlier reported association between IR and a LAC Carla Nasca deficiency, a candidate biomarker of major depression that is a risk factor for aging-associated memory decline, we are currently Rockefeller University, New York, New York, United States assessing LAC levels in this mechanistic framework. This model may provide endpoints for identification of early windows of opportunities for preemptive tailored interventions. Background: Early life adversities (ELA), such as variations in Keywords: Early Life Adversity, Glucocorticoids, Insulin Resis- maternal care of offspring, are critical factors underlying the tance, Glutamate, Memory Function individual likelihood to development of multiple psychiatric and Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. medical disorders. For example, our new translation findings suggest a role of ELA in the form of childhood trauma on fi development of metabolic dysfunction, such as a de ciency in M2. -

PDF of This Issue

MIT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Clear. 25°F (-4°C) Tonight: Clouding up. 7°F (-14°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Snow likely. 28°F (-2°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 119, Number 68 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Wednesday, January 19,2000 Dorm Construction Schedule Threatened IPOP Clearance Major Remaining Issue By Laura McGrath Moulton Sons. Inc. SIAFF RU'ORll:R "The permitting issue is the big- Groundbreaking for the new ger issue right now," Poodry said. undergraduate dormitory on Vassar The contractors "are chomping at the Street should occur early this spring. bit." "We have to get over all of the Poodry projects that the construc- regulatory hurdles before we can tion will take eighteen months. break ground, but that's in process "That's moving very quickly." now," said Project Director Deborah Poodry said. Assuming the project Poodry. does take eighteen months, construc- By that point, all parties hope the tion would have to begin by late Feb- weather will be mild enough to avoid ruary 2000 in order to open the dor- AARON MlffAUK-THE TErH digging through frozen ground. How- mitory by late August 200 I. Two large sections of roofing material fell off of building 18 Monday afternoon during windy condi- ever. Poodry said the cold should not Anne E. C. McCants. Founders' tions. The debris required heavy equipment for its removal. be a major issue for the contracting company, Daniel O'Connell's & Dormitory, Page 23 Spring 6.270 Teams Delayed by Fried Controller Boards By Sanjay Basu ties Period contest, are expected to "A big part of the contest is the sis. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1929-08-09

FREE MODEL AIRPLANES YANKEES SHAVE Get " Free Kit and Build VonneU Full Game From Athletics' Leac1 a Model Plalle. Tum WIU. 64 Will. StOlT to rale 6. on Page 5. -----------------------------------------------~~~~--~~~~~~~--~~----~----~~~~~~~------------~~~. VoIwne 29 6 PAGES AIl I 'ff.Jr;I~:_=~n:.-ln Iowa City, Iowa, Friday, August 9, 1929 hD~~ed";::" FIVE CENTS Number 6Q.. • SOVIET PLANE HEADS FOR UNITED STATES Col. Goehel in Burning Airpaine Graf Zeppelin Controller Decrees Great Britain, ';1 Woolaroc Due Carrie, Three to Student, Mwt Wear Death in Wyoming Cruises Near Shirt, at Stanford France, Italy ~ This Mornin~ OI\SI'ER, Wyo., Aug. 8 (f\P) , ..... Halfway Mark STANFORD UNIVERSITY, Cal., Split on Plan -M~j. W. I'. W arrlwel1, 36 years old, allli J~llr l Holty, 35 years Aug. 8 (AP}--Sun tan 01' no sun lan, Noted Honolulu Flyer old, /lJld George Cameron were ah Stanford mille students must wcar killed here tonight ",hen theIr I Messages State Liner shirts out oC doors In the future. Snowden Resume8 Figlit Will Land at Smith Illalle bursl Into Ilames, wenl Contl'ollel' A. E, Hoth or the unlver· Into a lall 8pln 'Uld lell several About 1,725 Milcs Against Young Plan ~lty so decreed today, I Field at 8 :30 huudred leet. The bodIes were of Settlement burncd bcynnd recognition. Out at Sea The ultimatum. characterized by , 10'11'& City Is to be visited ror the 1' h6 pilUle ",lIS piloted II,· some ot the students as "provincial (By The ASlIOClated Press) Wardwell, and a revel'slon to the mauve d~catle;' TIlE IlAGUE, Aug.